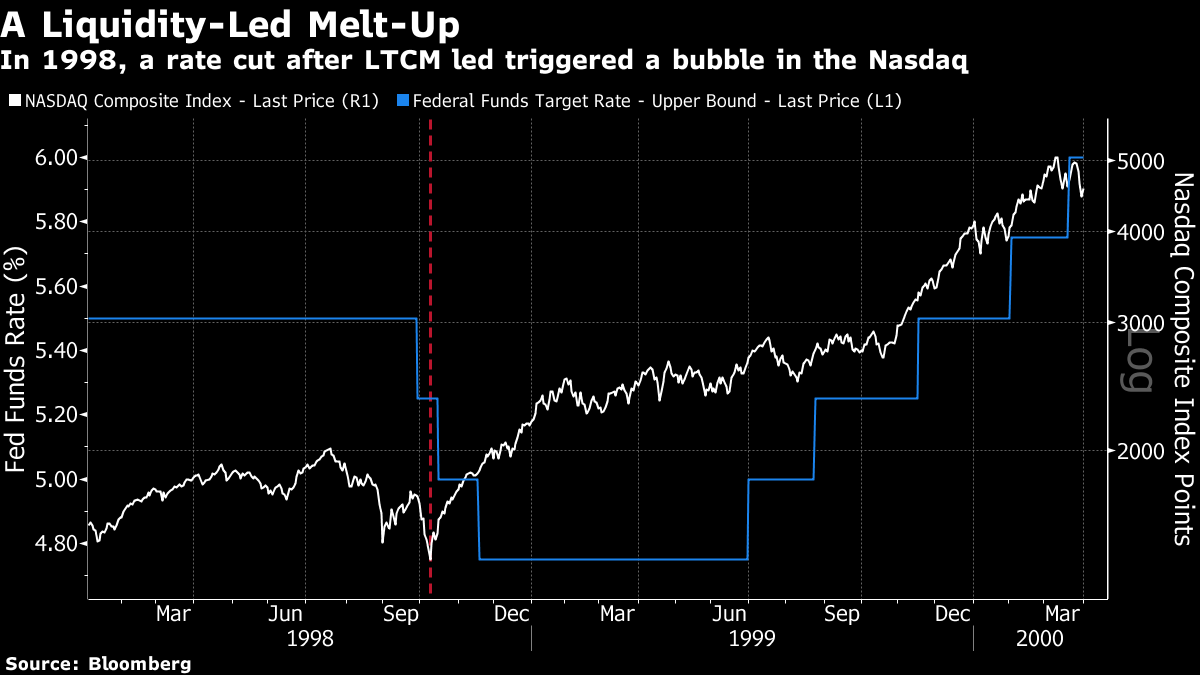

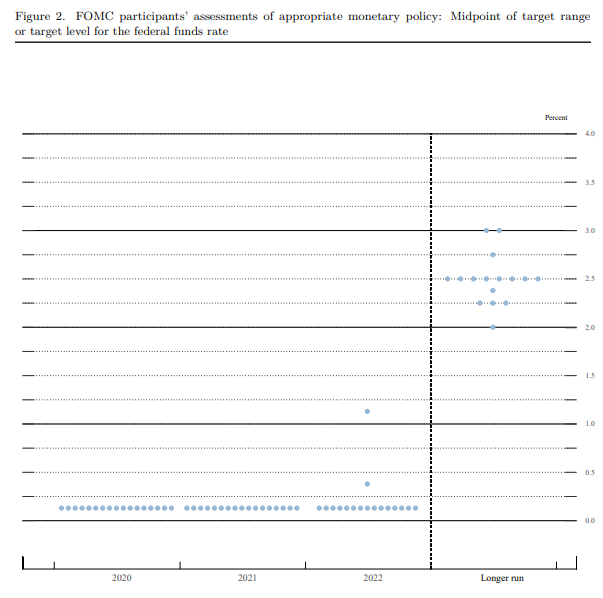

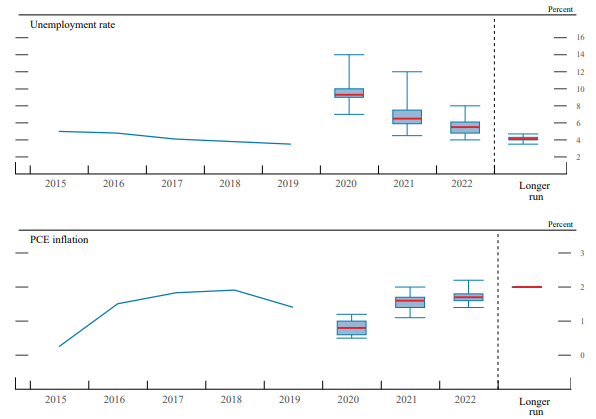

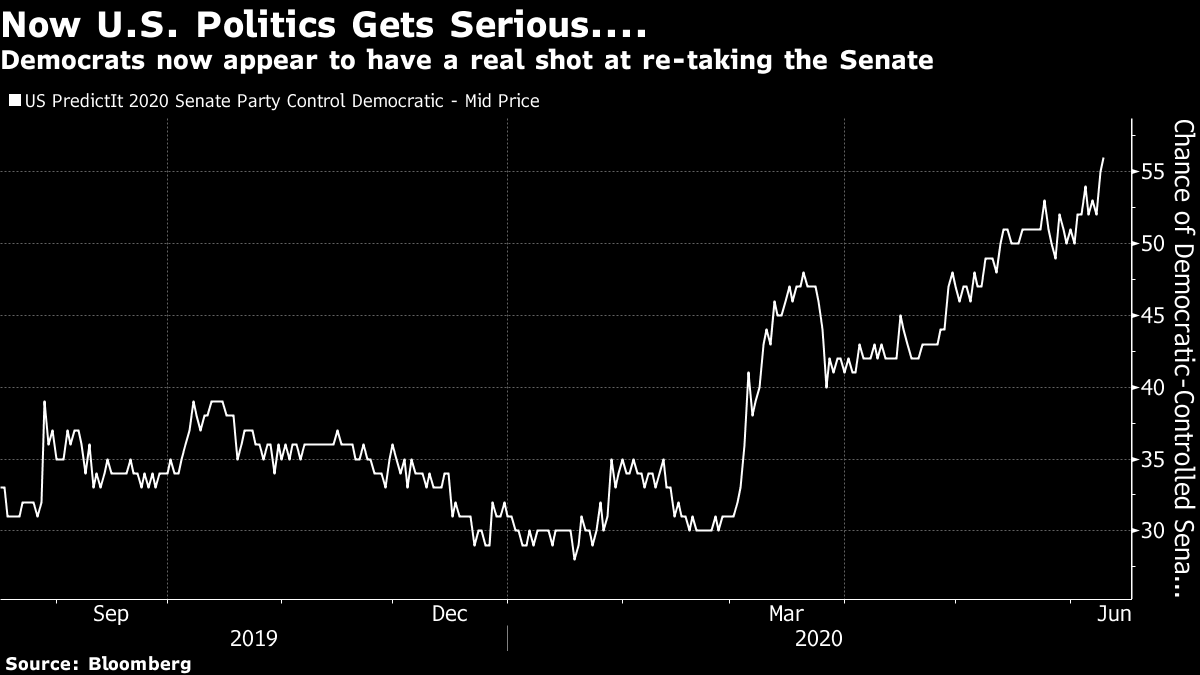

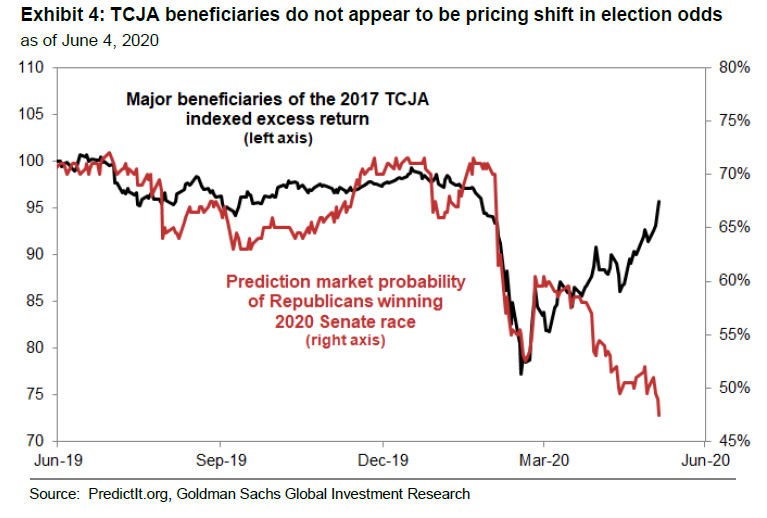

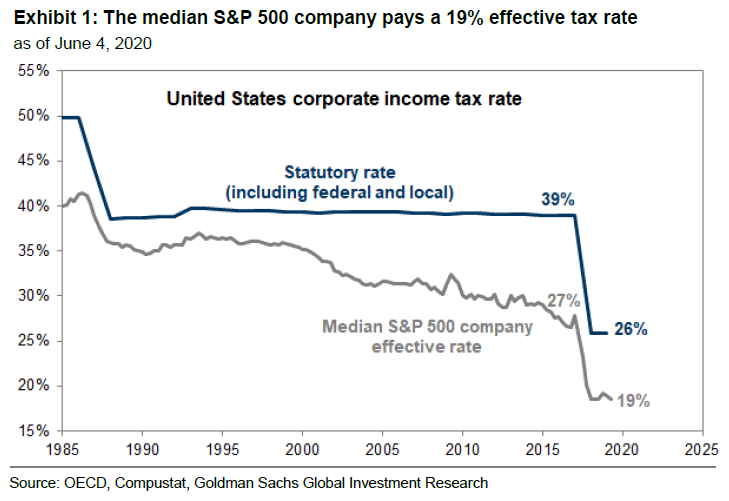

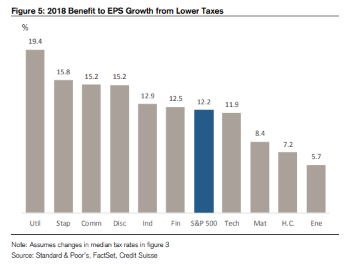

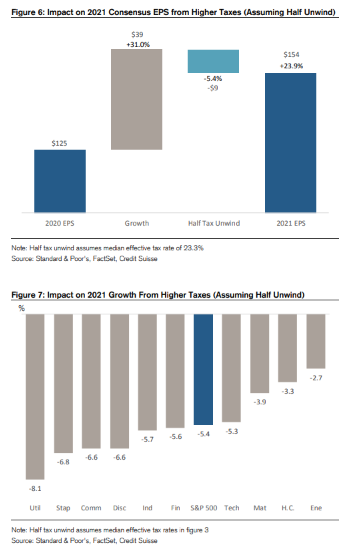

Party Like It's 1999 Are we ready to party like it's 1999? Jerome Powell saved the best for last at his Wednesday afternoon press conference to accompany the announcement of low rates stretching as far as the eye can see. Asked by Bloomberg News's Michael McKee if he was worried that a potential asset price bubble was forming, Powell gave a lengthy answer. Here is the most relevant passage: our principal focus though is on the state of the economy and on the labor market and on inflation. Now inflation of course is low, and we think it's very likely to remain low for some time below our target. Really it's about getting the labor market back and getting it in shape. That's been our major focus. I would say if we were to hold back because, we would never do this, but the idea that, just the concept that we would hold back because we think asset prices are too high, others may not think so, but we just decided that that's the case, what would happen to those people? What would happen to the people that we're actually, legally supposed to be serving? We're supposed to be pursuing maximum employment and stable prices, and that's what we're pursuing. He went on to add that the Fed did care about financial stability, and extolled the strength of the banking system, while reiterating that the Fed would focus on its real economy goals. With an economy now largely dependent on high asset prices and the ability of borrowers to roll over huge amounts of leverage, he was effectively disavowing any interest in acting proactively to puncture bubbles when they emerged. This is part of an ongoing controversy within central banking. Alan Greenspan, his predecessor from 1987 to 2006, is infamous for allowing two bubbles to expand (in tech stocks and then in mortgage credit), but did make a clear attempt to rein in the froth with his speech warning of possible "irrational exuberance" in late 1996. It is increasingly common to put asset prices and the financial system at the center of the economy, particularly since the last crisis. The work ofHyman Minsky, in particular, suggests that the real economy is vulnerable to asset price bubbles that burst, leading to bad loans and a domino effect of bankruptcies and bank failures. Where we are left looks disquietingly like the closing months of 1998, when the Russian default crisis had caused a virtual meltdown of the over-leveraged Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund. Credit markets were becalmed, and so the Greenspan Fed resorted to announcing an interest rate cut on a Thursday afternoon, unscheduled and while markets were trading, in an attempt to revive activity. That rate cut is marked with the red dotted line in the chart below. It worked not wisely but too well.  Money is fungible. Liquidity released to help re-float the credit market naturally found its way to where it could make the best returns, which at the time was in tech stocks. And so the extraordinary Nasdaq bubble was born. The Greenspan Fed was in an invidious position, facing what looked a real possibility of an early version of the credit crisis that would eventually transpire a decade later. But the decision to blink and allow an asset price bubble to form had long-lasting consequences. Powell's position, with the economy in a much weaker state, and with an election only five months away, is even more difficult. But the likely response by the markets, now that he has evidently decided to take the risk of going down in history as another great bubble-blower, will be to inflate a bubble. That creates a difficulty for investors. There is money to be made in a bubble, providing you get out before it bursts. Acting to take advantage helps to ensure that it inflates. Late 1998 was a terrible time to buy tech stocks on a 10-year view. It was a great time to buy them on an 18-month view. The chances are that many will now focus on the next 18 months. You can view the issue in terms of two Princes. Prince the musician tells you to party like it's 1999 (because the end of the world is coming). And Chuck Prince, then the CEO of Citigroup Inc., famously said in 2007 that while the music was playing, he had to keep dancing. The problem, for both princes, is what comes next, but there will be time enough to worry about that later. Certainly if anyone was worried that rates might be rising in the next 18 months or so, the Federal Open Market Committee did its best to allay such concerns. The new "dot plot" in which each governor's prediction for future interest rates is shown as a dot, can sometimes look a little like Jackson Pollock. This one is Piet Mondrian — the dots form a perfectly straight line for two years, with only the slightest of dissent that rates will stay exactly where they are until the end of 2022:  Anyone planning on taking a few speculative risks will be relieved to see this. Meanwhile, the Fed's economic estimates show clearly why the governors have decided to go this way. They expect inflation below the 1% lower bound of their target for this year, and don't expect the unemployment rate to return to its pre-Covid low even by the end of 2022:  Getting people back into employment will certainly help to combat the inequality that is causing such anger in the U.S. But any accompanying bubble in asset prices will widen the gap between the haves and the have-nots. The market reaction was perhaps a little revealing. Bond yields had shown some signs of rising again, particularly helped by last week's surprisingly strong jobs report. But 10-year yields dropped back to their old range, taking the dollar down in the process. Bonds and foreign exchange markets evidently thought that the Fed might be cowed by the risk of an asset bubble.  Stocks, however, didn't seem to have been bothered by such risks, and were down slightly for the day — even after the Fed's chairman had virtually promised not to reel in any speculative bubbles, should they emerge. It looks like the stock market is already taking liquidity from the Fed very much for granted. Meanwhile, on the Campaign Trail…. Something interesting is afoot in American politics. But it so far shows no impact on the market. Only a third of seats in the U.S. Senate come up for reelection each two years, and until recently there was widespread agreement that the Democrats had very little chance of wresting it from Republican control. That has changed. The Predictit prediction market now puts the chance of a Democratic-controlled Senate at about 56%:  This combines with a marked shift in the presidential odds since the street protests over racism began at the end of last month. In terms of the gap between the odds of a Democratic or Republican victory, things have never looked rosier for the Democrats. Meanwhile, the stock market has rallied on, almost unabated. Even though it rose and fell almost exactly in line with Donald Trump's chances of re-election for many months, that link has now been sundered. The rise in stocks isn't helping him, and the fall in his perceived chances isn't harming stocks.  This is strange because with the Senate now in play, the chance of a Democratic president being able to take market-unfriendly measures grows much higher. Specifically, if a President Biden took office with majorities in both chambers of Congress, a rollback of the signature Trump cuts in corporation tax would be a virtual inevitability. And yet the stocks of the companies with the most to lose have rallied as the Republicans' chances in the Senate have fallen, as this chart from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. makes clear:  Not all companies pay the same rate of tax, as some have much greater ability to use loopholes. The cut in the headline rate to 26% from 39% reduced the effective burden paid by the median S&P 500 company to 19% from 27%:  The companies that did best tended to be in the highly regulated sectors which derived most or all of their revenue from the U.S. This chart was compiled by Credit Suisse Group AG:  If and when the market wakes up to the Democrats' stronger prospects, then, we might well see utilities and staples come under pressure. As for the market as a whole, an increase in tax would straightforwardly reduce the likely earnings per share that could be shared with shareholders and should therefore, all else equal, bring down the stock market. Credit Suisse's own estimate is that earnings would drop by 5.4% compared to current consensus for next year, if the Democrats unwound only half of the tax cut:  There has been a lot else going on. But the likelihood is that unless Trump begins to bounce back soon — which is perfectly possible — rising political risk will help push the stock market down. Survival Tips I last had a haircut in February. Normally, regular haircuts plus a receding hairline ensure that hair never gets in my eyes. That is no longer true. So to survive such inconvenience, I recommend the solution cunningly devised by my daughter: a pony-tail.  At least it's cheered up my kids. I'll be glad when my friendly local barbers are open. For now, survival is easier with a pony tail. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment