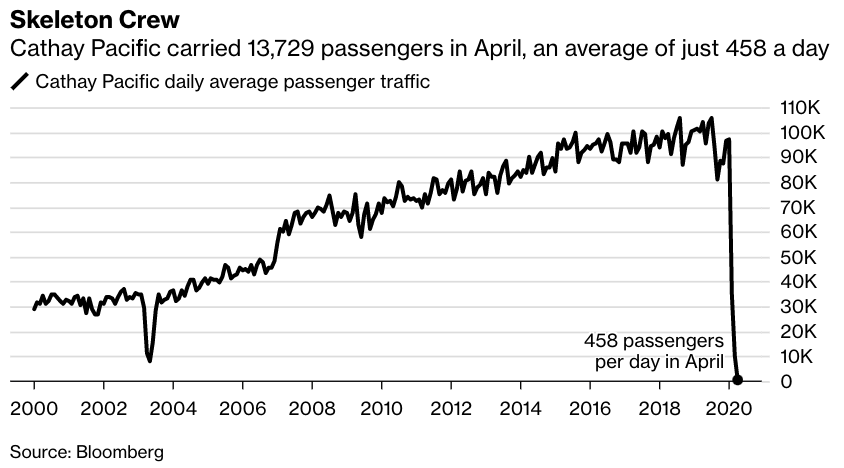

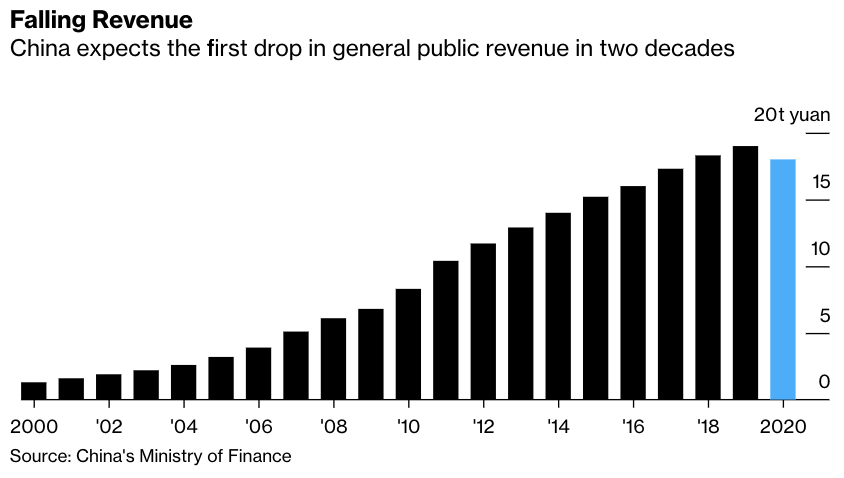

| Hong Kong's role as a global financial center certainly feels under threat. There are of course the protests, which this week passed the one-year mark. It was a march on June 9, 2019 against a since-withdrawn extradition bill that launched the historic pro-democracy demonstrations that have gripped the city ever since. Organizers estimated at the time that more than a million people took part that day. Hong Kong's economy, already weakened by the U.S.-China trade war, plunged into recession as a result of the unrest. Covid-19 made it even worse. The city's unemployment rate has risen in each of the past seven months and is now the highest it's been in over a decade. Beijing's reaction hasn't helped. Last month's decision to impose a national security law on Hong Kong has prompted many residents to consider leaving. In response, the U.S. has threatened to impose sanctions, while Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said this week he wanted to lead G7 nations in issuing a statement of concern about the legislation.  Demonstrators march during a protest in Hong Kong on June 9, 2020. Photographer: Justin Chin/Bloomberg Financial markets, meanwhile, have offered a more mixed picture. There's been gloom. Hong Kong's benchmark stock index, for example, has underperformed both the U.S. and China in the year since the protests began. The potential for capital outflows has been a persistent concern. Investors including Hayman Capital's Kyle Bass are placing bets against the city's currency. But there have been bright spots as well. A sale of shares in Hong Kong by JD.com, China's second-largest online retailer, was multiple times oversubscribed. Hong Kong's currency problem since mid-April has been that it's too strong, not too weak. And a survey of the city's money managers found that most are expecting an increase in assets under management over the next five years. Indeed, Hong Kong's advantages shouldn't be underestimated. It is a world-class city that by being part of China has had unparalleled access to mainland markets and wealth. But its relative autonomy has also given it things China lacks, such as open capital markets, the free flow of information and independent courts. That's been a powerful combination. Unfortunately, past success is no guarantee of future performance. Rescue Plan Hong Kong's troubles have hurt many of the city's companies, perhaps none more spectacularly so than its flagship airline Cathay Pacific. It began with the protests, which on their own eroded demand for flights to Hong Kong. But when some of the carrier's staff took part in the demonstrations, it put Cathay in the cross hairs of regulators in Beijing. Covid-19 has been even worse. Whereas the company planned before the outbreak to cut seat capacity by 1.4% this year, it ended up cutting almost all its flights as the coronavirus eviscerated travel. As a result, the carrier has been losing between $320 million to $390 million a month. Hong Kong's government finally took action this week to avert a collapse by injecting $5 billion through the purchase of about a 6% stake in Cathay. While the money will certainly help, it will only delay the inevitable if demand doesn't return or more fundamental changes aren't made to the company's business model.  Hard Times Things went from bad to worse for Luckin Coffee founder Lu Zhengyao this week. First was a report by Caixin that Chinese investigators had obtained emails showing he instructed financial fraud. Until then, there had been no suggestion of wrongdoing by Lu amid revelations of falsified revenue for the coffee chain. A few days later, Lu stepped down as chairman of Car Inc., a company he founded before setting up Luckin. Soon thereafter, it was revealed that a Beijing court had also frozen Lu's shares in Car Inc.'s parent company. With probes ongoing by both the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and Chinese regulators, there's a fair chance Lu's situation could deteriorate even further in the future. Purse Strings China's economy remains weak. Data this week showed that the prices factories are able to charge for their goods continues to decline. A private survey indicated a worsening outlook for employment next quarter. The mood has been made even more dour by a growing uncertainty about how much more stimulus Beijing is ready to provide. The central bank, long worried about debt, has held back on the sort of broad-based stimulus other countries have employed. And with tax revenue expected to fall this year for the first time in two decades, any additional surge in government spending to support growth will be just as challenging. That's not to say policymakers won't leap into action if things get really dire. But to convince them to do so, dire might have to get pretty bad.  What We're Reading: And finally, a few other things that got our attention |

Post a Comment