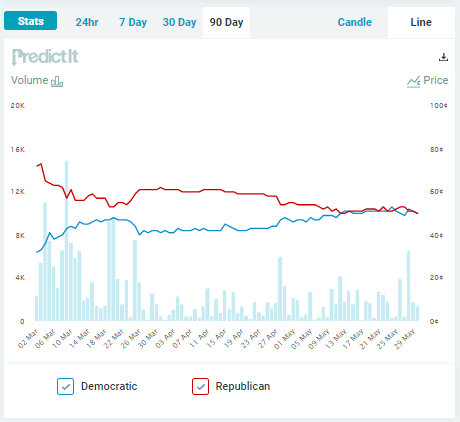

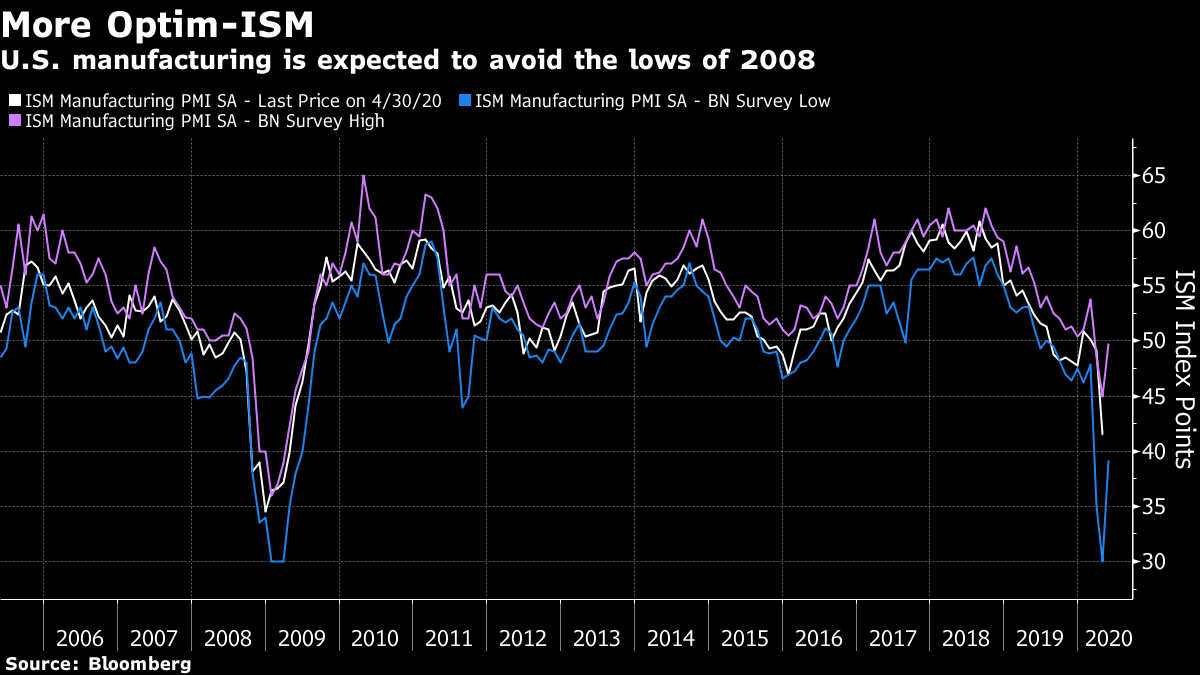

Conflict on Hong Kong's Streets June starts amid conflict. China's assertion of authority over Hong Kong has prompted commentary in the U.S. likening the moment to Hitler's annexation of the Rhineland or the Sudetenland. The situation is ugly and the ramifications of a further breakdown in the relations between the world's two biggest economic powers would, as has been widely discussed, be profound. And yet: President Trump's much-heralded press conference Friday afternoon was swiftly interpreted as adding nothing new to the considerable escalation in confrontation between the two countries. That helped U.S. stocks rally to end the week, and spurred an impressive rebound for Hong Kong's Hang Seng Index in early trading Monday. This is where the index stood at the time of writing (10 p.m. Sunday night in New York):  What has already happened should be profoundly worrying to anyone with business interests in Hong Kong. The U.S. has said it now has no basis to treat Hong Kong differently from mainland China, which implies serious problems for trade. The president did promise "strong" and "meaningful" actions Friday, even if he failed to specify what they might be. One other development will encourage those hoping for a repeat of last year's dynamic, when the rhetoric between the countries was very negative but they somehow avoided doing serious economic damage. China's currency last week approached its weakest level against the dollar since last August, which in turn was its lowest since early 2008. In early Monday trading the People's Bank of China set its yuan fix stronger, driving a noticeable appreciation by both the onshore and offshore versions of the currency. If Chinese authorities were trying to signal a ceasefire, this would be at least part of how they did it:  Conflict on America's Streets Meanwhile, there is the sudden breakdown of order in the U.S., which has managed to push even the coronavirus from attention. Readers will be aware of what is going on, with protests of both the peaceful and the violent variety spreading throughout the nation. They were sparked by an appalling video of a Minneapolis police officer killing a black man, while many watched and remonstrated, by keeping his knee pressed against his neck for nine minutes. Anger and revulsion are only natural in response; the arguments against violence are already well rehearsed. The question is whether these scenes, which look like a country spiraling out of control, will have an effect on markets. In the short term, there is good reason to question whether they will. The S&P 500 rallied after the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014, and after the disturbances that greeted the acquittal of the police officers who were filmed beating up Rodney King in April 1992. Both times, the events happened just when the market had suffered a minor tumble. The same is true of the U.K.'s FTSE-350 index after the police killing of a black man in North London, which led to a week of riots and looting in cities across the country. The breakdown in order was shocking and appeared almost total. But the stock market, which had just fallen badly amid the sell-off that followed the debt ceiling crisis in the U.S., rallied throughout the week of televised violence. Arguably, none of these events were quite as alarming as the disorder of the last few days in the U.S., although the London riots of 2011 certainly came close. But collectively they suggest that investors feel confident in disregarding riots like this. There is an underlying sense that order will be maintained. Going further back, 2020 is now firmly on course to be America's most traumatic year since 1968. That year saw the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, any number of riots in the streets — most famously in Chicago during the Democrats' convention — and a heated and divisive presidential election. Yet the stock market did fine. Aided by rallies before and after the victory of Richard Nixon in the election, the S&P 500 was up more than 10% for the year at one point. It gave it all up the following year, but the social and political trauma of 1968 wasn't reflected contemporaneously in stocks:  If there is any one reason why asset prices got through this annus horribilis relatively unscathed, it is the election. After many different candidates with deeply divergent political agendas had seemed plausible winners at one point or another during the year, it grew ever more apparent in the closing months that Nixon, a Republican thought to be far more market-friendly than his opponents, was likely to win. He sealed his victory in large part by campaigning as the "law and order" candidate. A skillful politician, he used a slick campaign to take advantage of the violence. The situation in the U.S. is fluid at present, but reports so far suggest that the violence has been seeded by anti-fascist left-wing agitators. If problems on the streets intensify, the chances grow that it could help another conservative president to win election on a law and order platform. If it helps the chances of a Trump re-election, that would be regarded as positive by the equity market. The relationship between the chances of Trump's re-election and the stock market has weakened. For months, the S&P 500 had risen and fallen in line with the Republicans' margin over the Democrats' chances of presidential victory, as recorded by prices on Predictit. For the last two months, however, the prediction market has been flat, showing a very slight advantage for the Democrats, while stocks have kept rallying:  Part of this is because former Vice President Joe Biden is a far less scary prospect for the market than some of the other Democratic front-runners of the last 12 months. But it may also be because nobody has any great confidence in judging the odds in these unprecedented conditions. One of the candidates has scarcely been visible. And uncertainty should be high in such conditions; a Nixon victory was far from obvious at the beginning of June in 1968. We get some extra inkling of this if we look at the volumes recorded on Predictit. Even the political junkies who trade there have seen little good reason to shift over the last two months, so the market has flat-lined with reducing volume:  Evidently, this cannot last. One or other candidate will at some point before long appear to take over as a clear front-runner. Meanwhile, the stakes are rising. This isn't just because the domestic and international situations are so febrile. It is also because the Senate now appears, from the betting markets, to be a total toss-up. For months, continuing Republican control seemed a certainty. Now, a Democratic presidential victory might come with control of both houses of Congress, which would open the way for some radical new policies, particularly on healthcare:  Political uncertainty therefore seems a certainty to return before much longer. But the campaign for now has some important effects that may be market-positive. The president wants a strong stock market, just as he also wants to appear strong in his dealings with China. The two conflict at present. The market might itself help to ensure that there are no further escalations over Hong Kong. And a deterioration in the situation on America's streets may lead to a resurgence in the odds of a Trump re-election. A weak U.S. response to China and further domestic disorder wouldn't be good for the country or the market in the long run. In the short run, just as in 1968, there is a combination of circumstances that could help the stock market rise. New Month, New Data With a new month come new data. The ISM manufacturing survey starts a busy week around the world that will include a European Central Bank meeting — with many more chances for the nascent common euro-zone fiscal policy to collapse or take a step forward — and U.S. unemployment numbers. The Caixin version of the China manufacturing index is above the 50 level that signals the difference between recession and expansion once more. It is higher than it was for several months last year. But the single greatest interest will be in the U.S. manufacturing data. Looking at the forecasts offered to Bloomberg by economists, the range is still wide, but both the highest and lowest estimates are higher than they were last month, and there appears to be unanimity that the ISM won't plumb the low it hit at the end of 2008. As returning economic optimism is palpable, a number nearer to the lower end of expectations would be a serious rebuff:  Survival Tips It's almost three months since I set foot in my office — and I am well aware that I am much luckier than many others because I still have a job that can be done easily from home. It gets much harder to deal with these conditions when there are questions over whether they are medically or morally justified. I wrote at length on the latter issue yesterday, and judging by the feedback so far, it touched a nerve. A lot of the trade-offs and decisions involved in dealing with the pandemic are practical, even if they are difficult to solve given our lack of precedents and knowledge of this virus. But the moral trade-offs affect people deeply. All further feedback on the moral issues would be gratefully accepted. For now, the funniest thing I've received so far is this song, which could be viewed as a critique of utilitarianism — or as an attack on Dominic Cummings, Boris Johnson's Svengali-like adviser, who allegedly suggested that herd immunity would be a good policy and "if that means some pensioners die, too bad." Either way, amid all the dilemmas and dissension, it cheered me up. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment