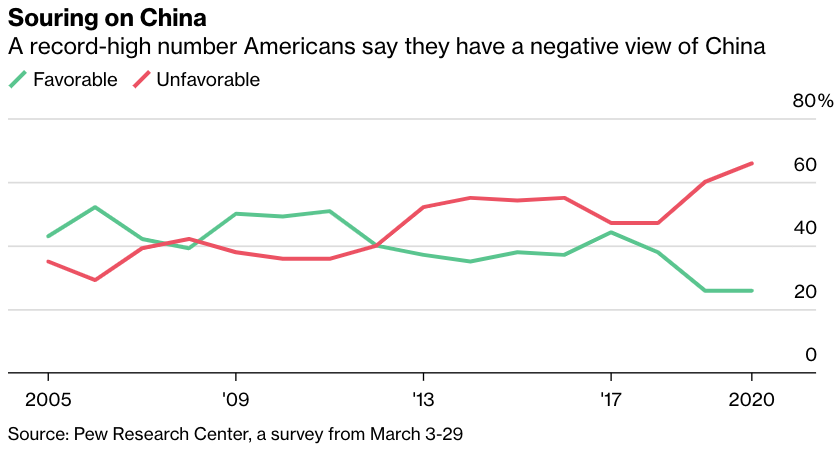

| Talking tough about China has become one of the more predictable features of American presidential elections. And while Beijing has mostly stayed out of the fray in the past, there's reason to suspect this time could be different. In the four years since the last election, China has shown a new-found willingness to mix it up in the forum of public opinion. State media bought four-pages in the Des Moines Register in 2018 to argue that the trade war was hurting Iowa's farmers. Last year, a Chinese diplomat spared on Twitter with former U.S. National Security Advisor Susan Rice. The risk of course is that a more aggressive Beijing begets a cycle of escalating rhetoric that unhinges the relationship with Washington. There have been hints of it before. The advertorial in the Des Moines Register, for example, prompted President Donald Trump to accuse China of meddling in U.S. elections. And the Chinese diplomat who feuded with Rice later propagated conspiracy theories linking American soldiers to the virus, which infuriated Trump and became one reason why the President insisted on using the term "Chinese virus." And as Washington has ratcheted up its criticism of China's handling of Covid-19, Beijing has ramped up its own rhetoric. When Secretary of State Michael Pompeo said there was "enormous evidence" linking the virus to a lab in Wuhan, China's foreign ministry challenged him to show it. State media was more direct, accusing him of telling lies and "spitting poison." It's hard to imagine either side toning it down. Even before Covid-19, China seemed certain to loom larger than ever in this year's U.S. election thanks to tensions over trade and technology. Now with more than 70,000 Americans dead and millions out of work, the relationship promises to be at the top of many voters' minds.  That's something both Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, his presumptive challenger this November, appear to have noticed. Each is already trying to paint the other as being weak on China. For Beijing, the implications reach beyond ties with America. Authorities are dealing not just with brewing angst abroad, but also simmering unhappiness at home. That makes sitting on the sidelines a less tenable option when Trump and others blame the Communist Party for Covid-19.

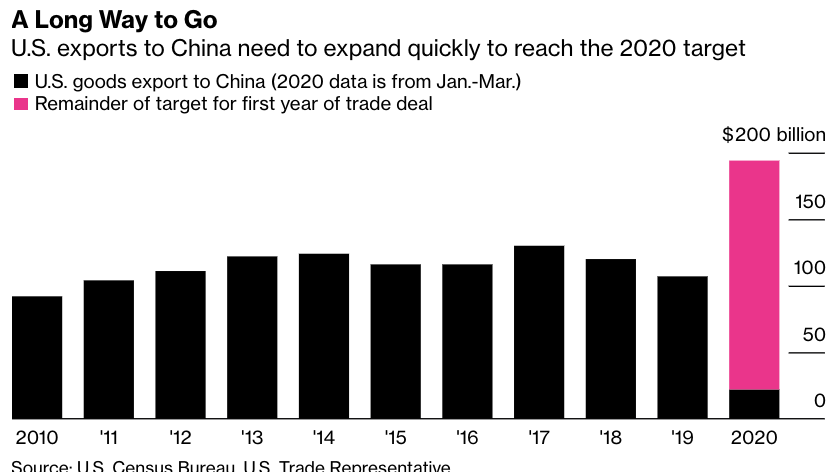

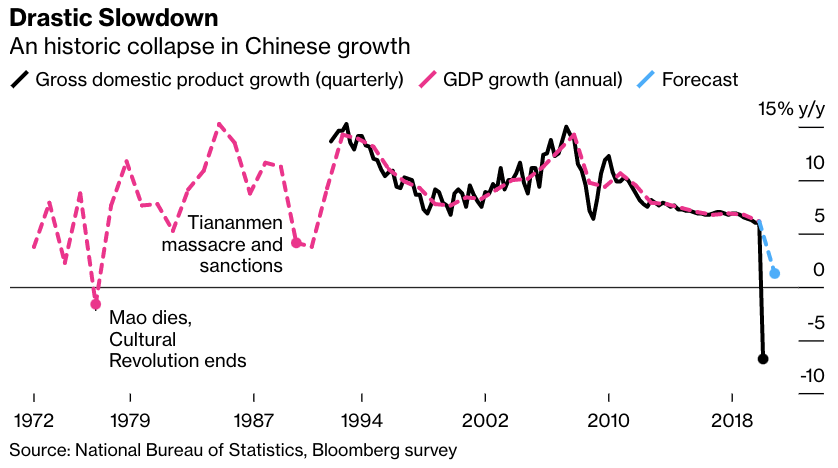

But not all hope is lost. There are still plenty of people on both sides making the point that a breakdown in the relationship is bad for everyone. China's ambassador to the U.S. took such a measured approach this week when he wrote in the Washington Post that the world's foremost powers should put an end to the blame game. It's also worth noting that amidst the heated rhetoric, both countries have abstained from directly attacking each other's presidents. The relationship between Trump and Xi Jinping has become the most reliable lever for cooling tempers. It was a phone call between them in late March that put an end to Trump's use of the term "Chinese virus" and the Chinese diplomat's conspiracy theories. A lot can and probably will happen in the months ahead that exacerbates tensions. Whether it irrevocably damages China's relationship with the U.S. is far less certain. Trade Deal It's easy to forget that U.S.-China ties began the year on a high note. After three years of tariffs and tensions, Chinese Vice Premier Liu He signed the phase-one trade deal in Washington on January 15. The world looks very different four months on as Liu and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer prepare for their first meeting to review implementation of the deal, which could take place as soon as next week. It's hard to imagine Covid-19 not being part of that conversation, but any change to the pact appears unlikely. Trump has already signaled that he expects every pledge to be met, even if that looks more challenging than ever for Beijing to achieve. It's a position Trump will find hard to move off of with Joe Biden's campaign already suggesting that the deal made him weak on China during the early days of the outbreak. What was once supposed to bolster Trump's reelection chances looks ever more like a hindrance.  Origin Search China has so far resisted the notion that an independent inquiry should be conducted into the origins of the coronavirus. When Australia proposed it, China's ambassador to the Canberra blasted the idea and said it was likely instigated by the Americans. There does, nonetheless, appear to be growing support for one to happen. The European Union this week said it will put forward a plan for such a probe later this month. The World Health Organization also said it's considering a new mission to China to seek the source of the virus. That puts Beijing in a tricky position. U.S. assertions about the lab in Wuhan and claims that China has withheld information have fueled Chinese concerns that an investigation will be used to blame it for Covid-19. But resisting growing international consensus for a probe could just as easily paint Beijing as the bad actor. Ultimately, the outcome will depend on how skillfully China can find some middle ground. GDP Target With the National People's Congress officially rescheduled for May 22, there has been much anticipation for where China might set its 2020 growth target. Traditionally announced on the first day of the event, a high number would have suggested more stimulus was on the way. A lower one would have signaled Beijing was ready to shoulder more economic pain to avoid a potential surge in debt. It now looks like we could get neither. It was revealed this week that policy makers are considering breaking with tradition and avoiding a numeric target altogether. It's not a new idea. Economists including Ma Jun, an adviser to the central bank, have publicly advocated scrapping the target as it would free policymakers to focus on other factors, such as employment and financial risk. If authorities do decide to forgo a numeric target for 2020, it could well be the start of a new tradition.  What We're Reading And finally, a few other things that got our attention: |

Post a Comment