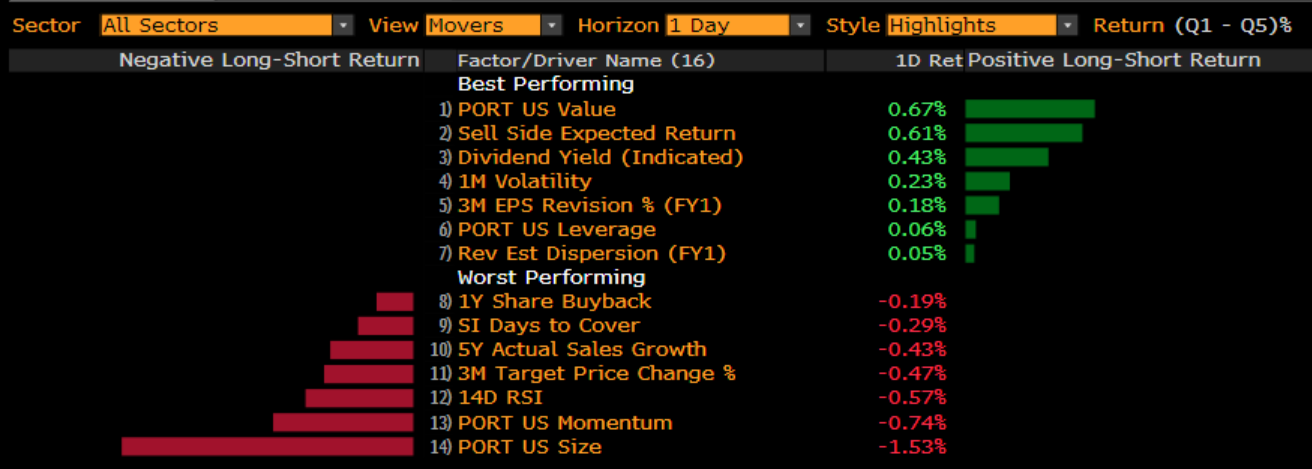

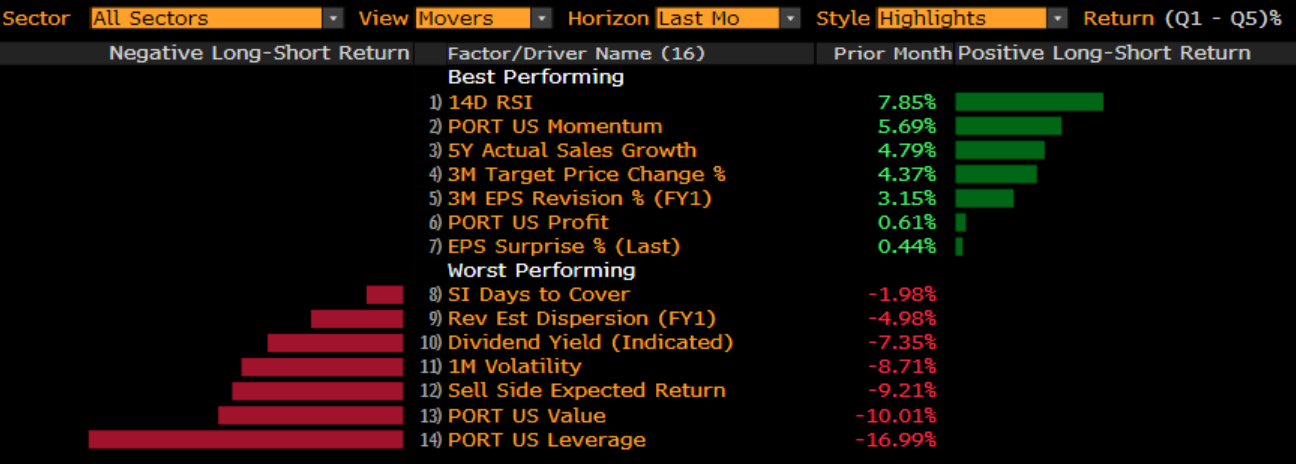

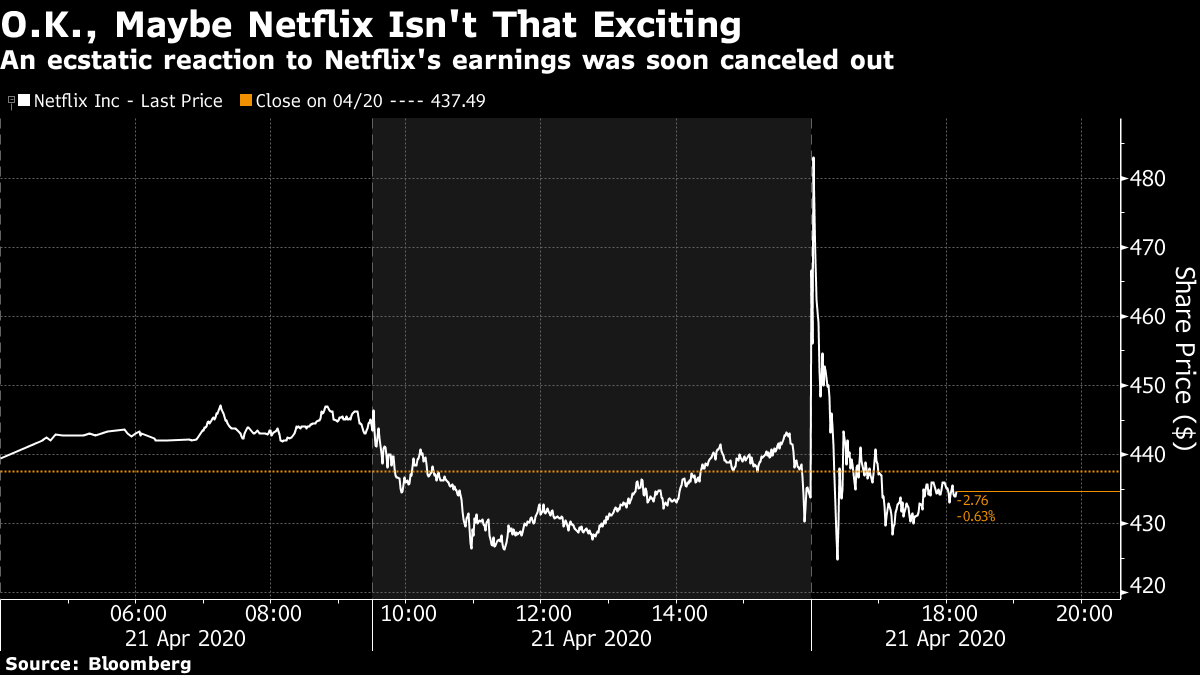

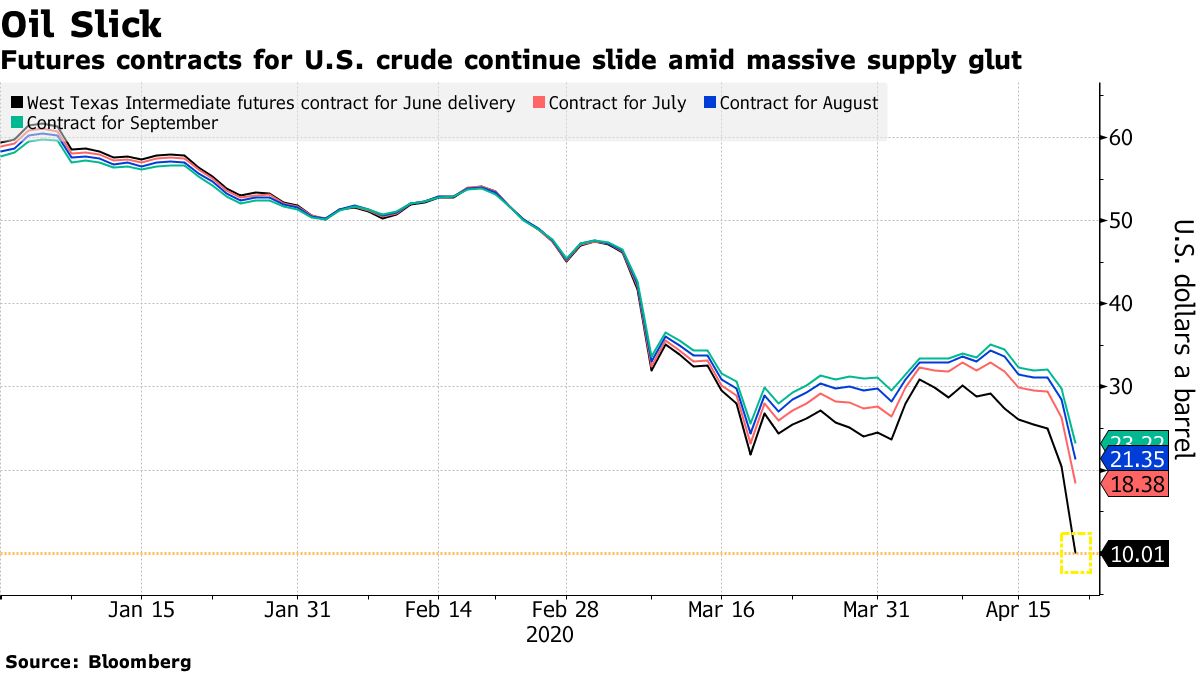

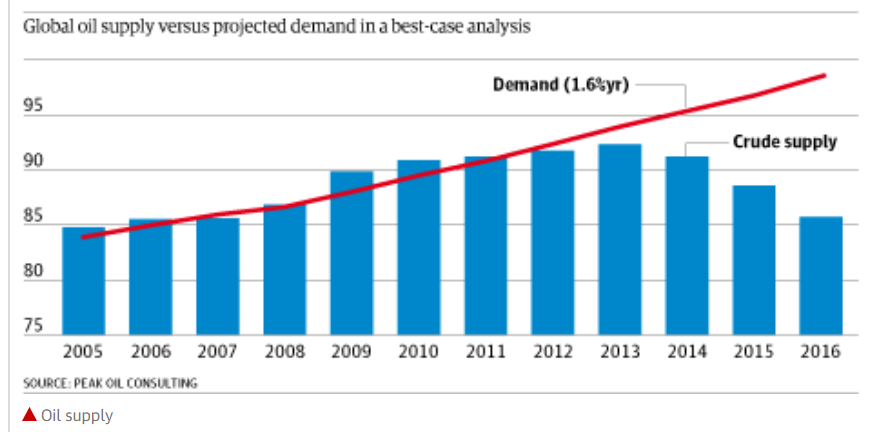

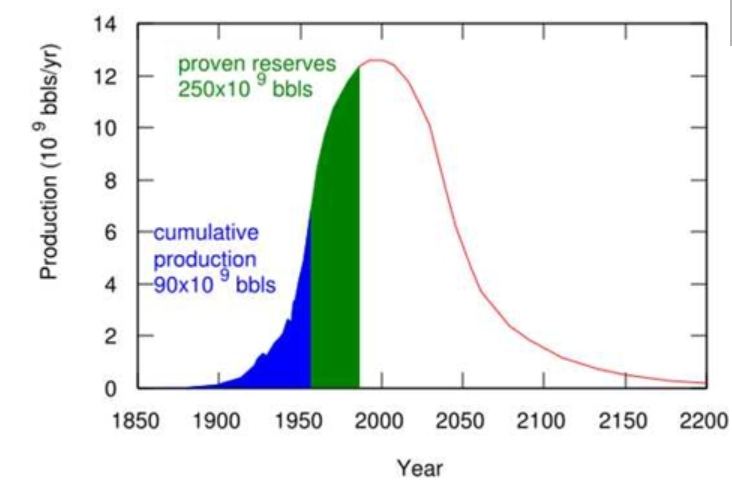

From Drowning in Oil, to Peak Oil, and Back We have a new narrative, and it has us floating inexorably to hell, borne on a flood of oil. That, at least, is the story being offered to explain why markets have turned decidedly risk-averse again, with U.S. stocks suffering their worst day since April 1. Meanwhile bond yields are falling, with the 10-year Treasury below 0.6% once more. Put these together and stocks are lagging behind bonds by 33% since they peaked in January:  As stocks' rally had looked premature and overdone, this isn't necessarily bad news. Further, it is interesting to look at a radiography of how the U.S. market behaved, using the Bloomberg factor analysis function (FTW on the terminal). It is too soon to build much on this, but for the first time in a long while, the strongest-performing factor Tuesday was value, while large companies and stocks that had momentum behind them did worst:  This was an almost exact reversal of the trend of the last few weeks, when the market rallied in a narrow way behind a few large companies perceived as having strong growth prospects. Over the last month, heavily leveraged and value stocks were pummeled, while growth companies with momentum outperformed. This is very unusual during a rebound, and always suggested that this was more of a rally within a bear market rather than the start of a new bull phase:  With information technology the worst-performing sector, this looks like a straightforward "risk-off" correction day, which might be healthy. After-hours trading in Netflix Inc. suggested that even appetite for streaming might be wearing out. The darling of the moment gained roughly double the number of forecast new subscriptions in the first quarter (and much better than warned by skeptics like me). Yet:  The reason for the gloom was, of course, the continuing pain in the oil market. Horrible performance by contracts for delivery of crude in June, July, August and September swiftly dispelled any optimism that Monday's crash into negative pricing was a unique technical accident afflicting only the May contract:  Historic changes are afoot in the energy market. It is no longer possible to deny that. In the words of Edward Morse, the veteran oil industry analyst who now heads commodity research at Citigroup Inc., the future could be "a benign low cost price arena or a higher cost politically charged one." Whichever comes true, the growth of the U.S. position in the wake of the shale revolution has left it at the center of what he calls the "management" of how the energy order will evolve. The glut of supply shows that it isn't yet ready for that role, just as Saudi Arabia and Russia are working out their own changed parts. But a new order will emerge. What's important is to avoid seduction by an exciting narrative, or to over-extrapolate from the present into the future. Oil, with all its attendant geopolitical drama, is particularly susceptible to grand theories that go further than they should. Morse makes this fascinating point about beliefs in 1999, the last time when oil was anything like as cheap as it is now: Oftentimes a prediction of the future that seems almost axiomatic could instead be radically upended: in this case a future of abundant oil supply and low prices. Thus, it is worth highlighting the March 4, 1999 issue of The Economist magazine, focusing on $10 oil forever — except that oil might fall to $5. At that time, four OPEC countries — Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, and Venezuela — sitting on huge low-cost oil reserves, were planning to add 1-m b/d of oil production per year for the next decade, if not longer. But, five and ten years later, their group production was lower than it was in 1998. That Economist cover has indeed gone into history, as has a follow-up produced in October 2003, in the wake of the invasion of Iraq:  What instead happened was the greatest oil spike in history. With low prices failing to encourage extra production, the oil industry was taken completely by surprise by the rise of China, and of other emerging markets, and the huge demand for oil that came in its wake. Add in financial speculation, and oil prices would reach an all-time record by the summer of 2008. Again, the price gave rise to an explanation, or a narrative — not the other way around. By 2008, many took it as axiomatic that the world had reached "peak oil" and that production would begin a slow decrease while prices ground inexorably ever higher. This view was everywhere that year, and had great charts to back it up. In October 2008, this graphic accompaniedan alarming piece in The Guardian, which detailed a task force that had been appointed to help prepare the U.K. for the coming peak and then decline in oil production. Such diagrams portray a sense of inevitability — note that this was a "best case" scenario:  Another perfect example of the genre came in Seeking Alpha, complete with a battery of charts making clear that oil supply had nowhere to go but down. Here is one of the neatest:  I think it's fair to say that none of the peak oil scenarios were consistent with prices going negative in the spring of 2020 owing to a glut of supply. This isn't to say that we will emerge from this predicament unscathed. The bursting of the oil bubble in 2008 hastened the dislocation of markets that was about to plunge the world into crisis. The long-term fall in prices that followed came mainly because the spike had spurred the growth of the shale industry. But it would be wise not to assume that we are doomed to float on an oil lake for eternity, and instead try to work out what the next narrative is going to be. Meanwhile, Back in Europe... Oil has slipped into unprecedented territory this week, so it has been easy to miss the goings-on in Europe. They are very concerning, and go far beyond the coronavirus. Last month, spreads between yields on Italian and German government bonds ballooned after Christine Lagarde, newly installed president of the European Central Bank, said that it wasn't her job to close them. She then apologized for the comment, and the ECB went to great lengths to narrow the spread. Now it is widening again:  Is Italy, recently stricken by the virus, to be helped by the rest of Europe? After an editorial in Germany's Die Welt argued against aid that would inevitably find its way into the hands of the mafia, it is plain that a fight is in prospect, and that European unity is at stake. Italy isn't Greece (which, ironically after all its tragedies of the last decade, has handled the pandemic better than almost anywhere else on the continent), and its economy is on such a scale that it will be far harder for the nations at the center of Europe to play hardball. Meanwhile, the heart of Europe's problem remains. Its banking system entered the 2008 crisis in a bloated state, bought a lot of the U.S. credit securities that subsequently went sour, and remains hobbled. As the Federal Reserve and the ECB have deployed their bazookas over the last few weeks, shares of U.S. banks have recovered, as have those of non-financial European companies. Shares in euro-zone banks have not, and are now at a fresh low:  On Thursday, EU ministers meet by teleconference to discuss their response to Covid-19. The published agenda includes work on a "European Recovery Fund." The EU has had plenty of make-or-break, existentially important summits over the last decade. This could be another one. Its financial system is in a weak condition, even after much central bank largesse. The coronavirus could yet turn out to be the disease that at last tears it apart.

Survival Tips Music has powers to make people feel better. In Spain, hit by one of the worst Covid outbreaks, the song on everyone's lips is Resistire ("I will resist"). This is the latest version, prepared in conditions of social distancing. It has also spread to Mexico, where another bunch of musical stars have made this slightly glossier and lisp-free version, as that country braces for what could be a serious outbreak. A sweet solo version, recorded by an American with an impeccable Castilian accent, can be found here. The original version , which goes back to the 1970s, was by the Duo Dinamico, and can be found here. Should I point out that all these versions seem to owe a lot to the karaoke classic "I Will Survive" by Gloria Gaynor, which might also make a good anti-Covid anthem? I will resist. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment