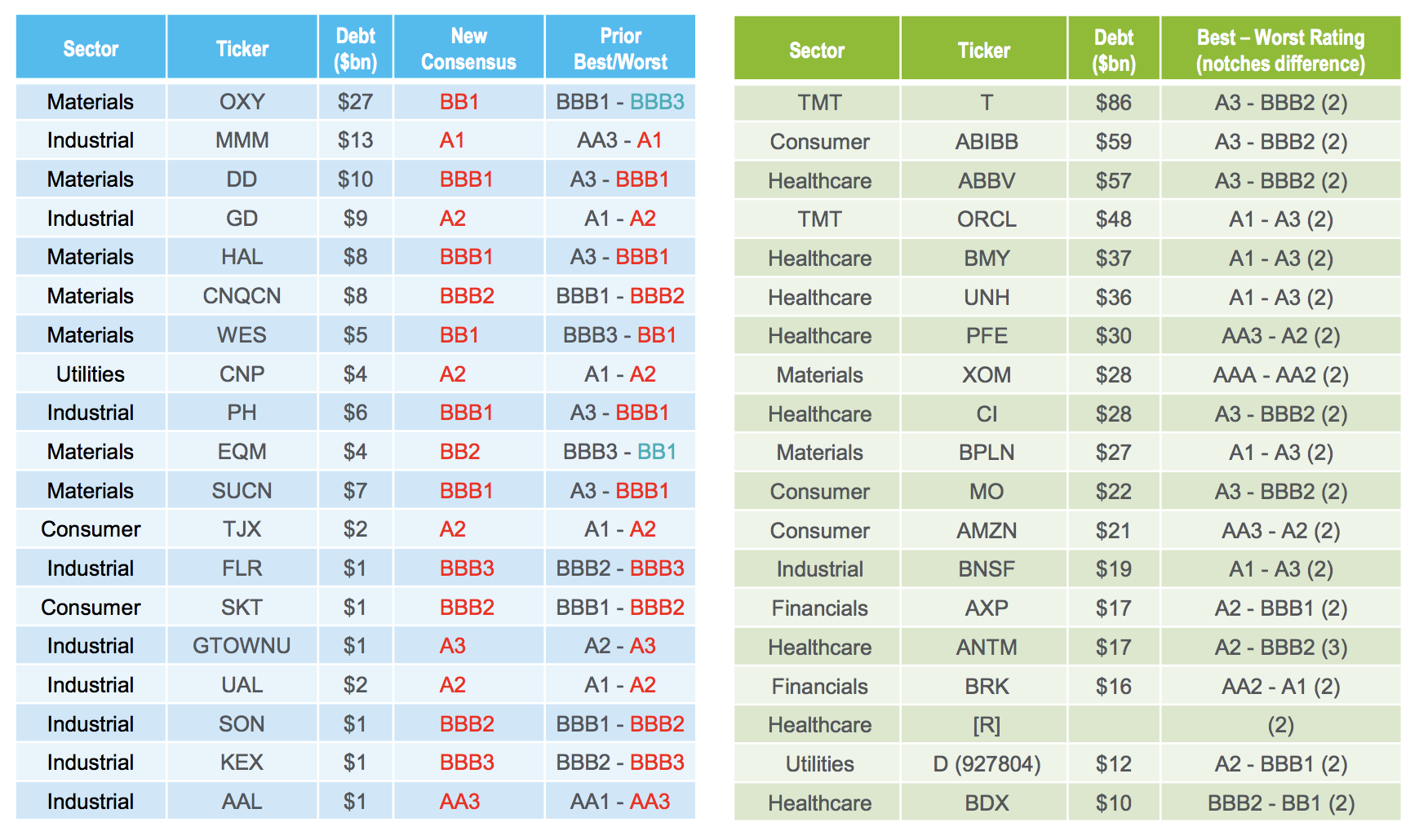

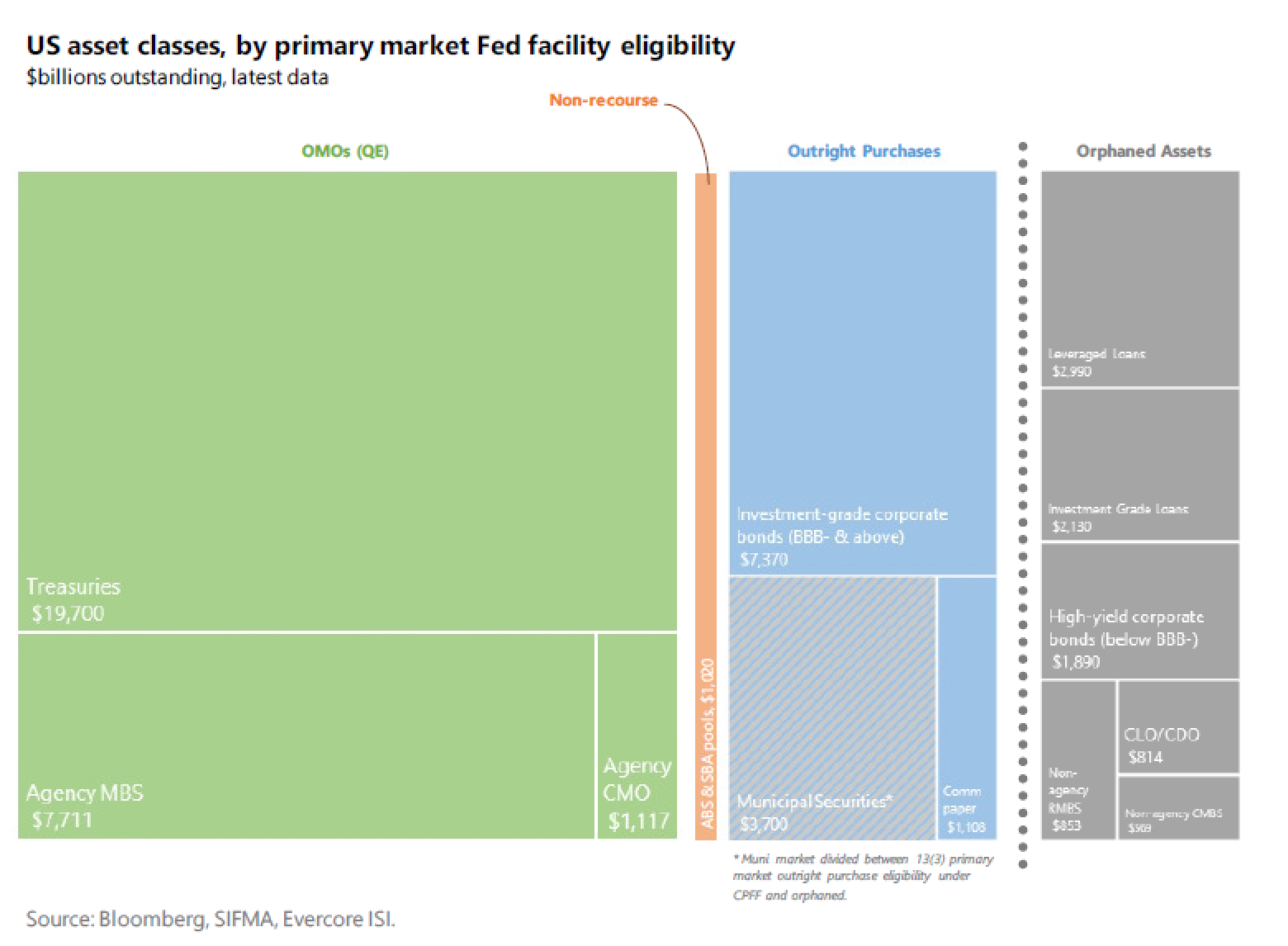

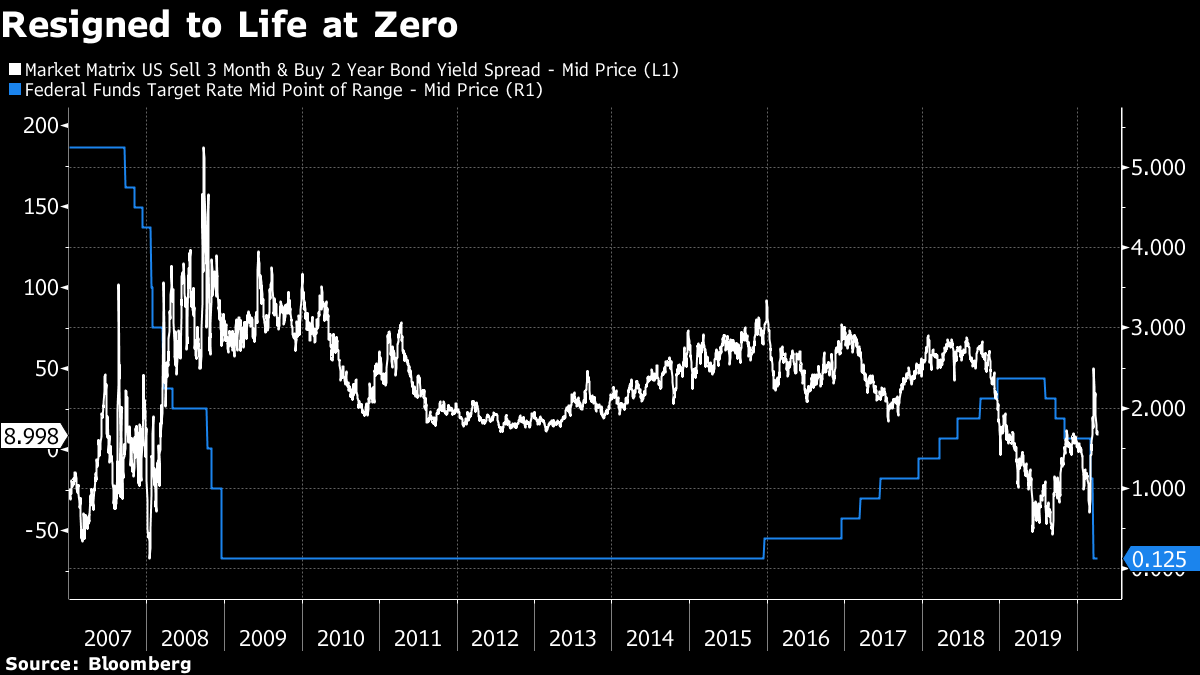

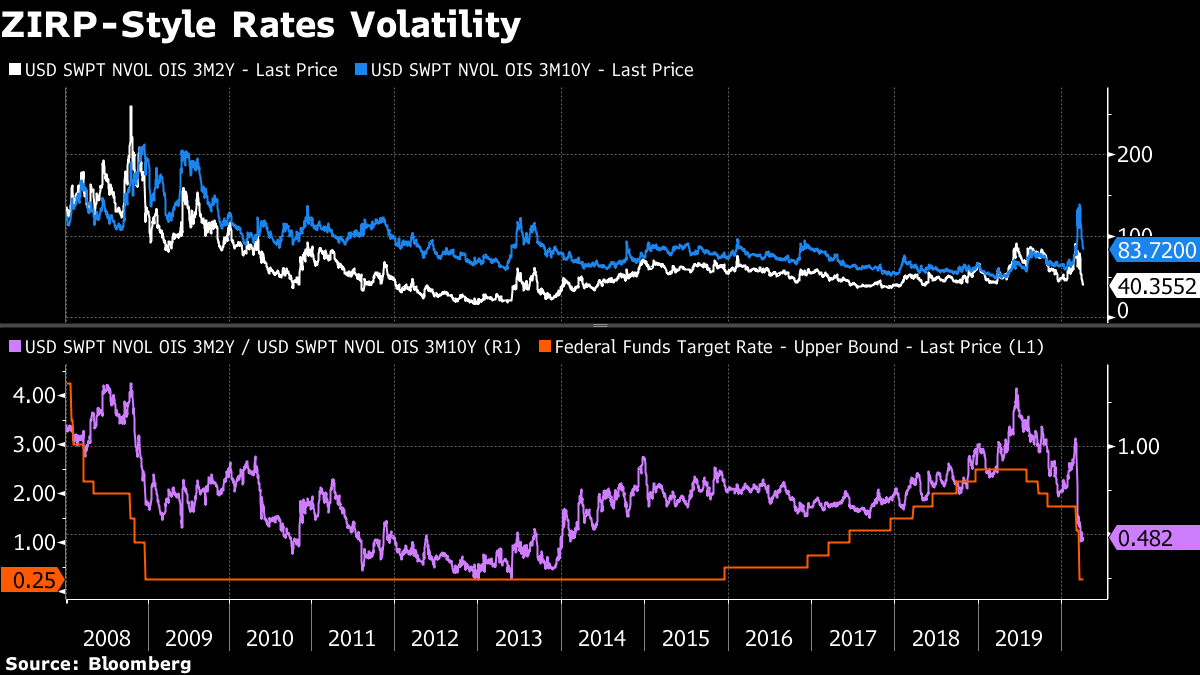

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that wonders how quickly the bond market will internalize the lessons of the last time the Fed cut rates to zero. --Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter Junk Food for Thought As the Federal Reserve cranks up its slew of new credit-support programs, with the potential for more to come, there's an increasing debate over whether or where red lines should be drawn around no-go areas. Like avoiding junk-rated debt. Former Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Bill Dudley suggests that market is composed of companies leveraged up via private-equity buyouts -- actors who "made a conscious choice to take on more debt in the hopes of generating bigger returns for equity holders." But that's not universally true. Consider the case of junk-bond issuer Tesla. No buybacks. No dividends. Even some of its debt issuances have tended to be dilutive to shareholders, as they've been convertible. Dudley argues that the Fed would be creating "moral hazard" by bailing out the high yield market, and suggests it could be "more expensive" than other initiatives because of an additional use of U.S. Treasury funds. But it's unclear why a special purpose vehicle for high yield would have to be more capitalized, and not just more leveraged via funds from the Fed. As it stands, the central bank is deferring to two different institutions in deciding which asset classes get adopted and which get orphaned. One is Congress, but the second is, effectively, ratings agencies. The Fed's goal in rolling out a suite of emergency measures is to short-circuit coronavirus-induced impulses to financial markets that would adversely affect its ability to achieve its dual mandate. Fed easing is inherently counter-cyclical. Ratings downgrades amid the global economic curtailment in activity is highly pro-cyclical, and there's more pain in the pipeline. The market carnage means that some credit ratings have migrated to the previous worst rating (such as 3M Co.), and in other cases there is still wide dispersion that's likely to be resolved with more downgrades to the low end (such as Exxon Mobil Corp.), according to Daniel Sorid, head of U.S. IG credit strategy at Citigroup Inc. ``Many of the largest IG issuers' debt ratings continue to reflect differences of two notches (or more) between the three major agencies," he writes. "In many cases, we expect the most optimistic agencies to face pressure to cut."  Citigroup Citigroup Dudley's feared slippery slope may in any case be unavoidable, at least in a small way. That could happen when the central bank starts buying investment grade corporate bond ETFs, because -- fun fact -- most such funds hold a small amount of high-yield debt. LQD is one of the biggest, with $39.5 billion in assets, and 0.82% of its holdings are BB-rated (in other words, junk). For the iShares Short-Term Corporate Bond ETF, the proportion is 1.33%. The share is 0.86% for the iShares Broad Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF, and 1.67% for the iShares 0-5 Year Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF. (All figures are as of April 1.) Meantime, the Fed's Main Street Business Lending Program suggests that the credit quality of beneficiaries is not the top priority in determining access to liquidity assistance. It could be argued that the Rubicon of credit risk has already been thoroughly crossed; all distinctions from here are a matter of degree rather than kind.  Evercore ISI Evercore ISI Keeping all this in mind, Roberto Perli, founding partner of Cornerstone Macro, quipped, "The time to worry about moral hazard and the like is before a crisis, not during a crisis. A similar thought process applies to the banks in providing the (federally guaranteed) money going to small businesses. As University of Oregon professor and Bloomberg Opinion columnist Tim Duy tweeted, "if you aren't making bad loans in this circumstance, you aren't doing it right." Maximizing winning, as much as victory is within the scope of possible future economic and financial market outcomes, might entail some more openness to losing. Life at Zero, Déjà vu All Over Again The last episode of U.S. interest rates at the zero lower bound wasn't quickly accepted and internalized in all bond market metrics. And though acceptance is a lot quicker in coming this time around, it still hasn't fully sunk in. All of the limited experiences with cutting rates to, or below, zero, have shown difficulties in getting them higher thereafter, due to sinking global so-called neutral rates or the persistence and magnitude of the economic shock that prompted the easing in the first place. This episode, as with the financial crisis, had a lot of both. If investors are convinced the economic shock is sufficiently large to keep rates at zero for an extended period, the spread between three-month and two-year Treasury yields should be fairly small. That wasn't the case in 2008: that gap lingered at 75 basis points for most of 2009, which reflected expectations that before long, this too would pass and the Fed would be back to hiking. It wasn't until 2011 (during fears of a double-dip recession) that this spread compressed to tiny levels. This time, it barely broke 50 basis points and now lingers in single digits, lower than any time from 2009 through 2018.  George Pearkes at Bespoke Investment Group provides a useful lens for viewing the global sovereign curve. "Monetary stimulus around the world is proving much more successful in reducing the front end than fiscal stimulus is in pushing up the long end," he writes. Investors fearing a repeat of the 2008 experience might be wondering not why 10-year Treasury yields are so low, but why they're so high. One possible explanation is that the Fed's zero (and not negative) lower bound is seen as sufficiently credible that the longer end is predisposed to send a more optimistic message given a perceived asymmetry in the possible distribution of outcomes for short rates. In either case, swaptions are showing a bit of trepidation that any outcomes are set in stone. The implied volatility of two-year yields over the next three months is at historically depressed levels, but was materially lower for virtually all of 2012 and most of 2013. Current readings are consistent with what prevailed from mid-2017 until the fourth quarter of 2018 – the most accelerated part of the Fed tightening cycle.  The implied volatility of 10-year yields over the next three months went haywire when markets were in peak liquidation mode, but has since settled. This volatility has compressed meaningfully, but perhaps could go even further, to the extent that the Fed is able to employ forward guidance and asset purchases that effectively cap borrowing costs at the longer end. "Indeed, in general one expects short term rates around the zero lower bound (ZLB) to be a volatility dampener," writes BofA Securities Bruno Braizinha. "That is clearly the case at the front end of the curve, but the flattening pressure that lower neutral rate expectations put on the curve should serve as an amplifier and propagate its impact out the curve." Don't Wait, Intermediate and Accommodate One common criticism of traditional central bank easing is that it runs smack-dab into the law of diminishing returns, and before long is just pushing on a string. A rate cut of 25 basis points – even if transmitted one-for-one across the curve – may not move the dial for anyone considering purchasing a house or durable goods like a car. The Fed's recent regulatory easing is designed to avert such a fate. The central bank elected to exclude Treasuries and reserves from the assets for which banks have to maintain capital (the supplementary leverage ratio, or SLR). That's material relief given how a deluge of Treasury issuance and jump in bank reserves could otherwise impinge on lending. "Even as the Fed has in recent days called on banks to use their capital and liquidity buffers to support lending to the real economy and distribute liquidity from Fed programs to the wider financial system, the big banks have generally acted as if they are – or could become – balance sheet constrained," writes Evercore ISI's Krishna Guha. "The big banks faced a dual squeeze – from drawdown of loan facilities / increased financial market intermediation and from the growth in central bank reserves driven by surge market-functioning QE and the start of credit programs – all of which count towards the supplementary leverage ratio in normal times." This is all about enlisting banks as allies in the financial fight to mitigate the economic fallout from the coronavirus by providing more balance-sheet space. "More balance-sheet capacity also allows banks to buy assets and pledge them at the Fed via the new alphabet soup facilities, making them more effective," writes TD Securities' Priya Misra. "By exempting Treasuries from SLR, the Fed may have removed one potential seller of Treasuries from the equation." Right now, banks certainly aren't the proximate cause of the imminent downside in global growth, as was the cause in 2007-2008. But when the economy weakens, by nature they tend not to be counter-cyclical. For example, while Bank of America has let 50,000 mortgage borrowers skip payments, it's also aggressively tightening standards for homeowners looking to raise funds via home equity lines of credit. That's why Skanda Amarnath, director of research and analysis at Employ America, urges government interventions to ensure that financial institutions are fully enlisted as partners in preventing economic damage. "It is because we are in a period of contracting economic activity that each bank is increasingly unwilling to voluntarily concede losses that flow to the benefit of borrowers," he writes. "Voluntary actions will fall short; regulators will need to synchronize the effort so that all banks give borrowers a fair opportunity to defer debt service payments through this crisis." |

Post a Comment