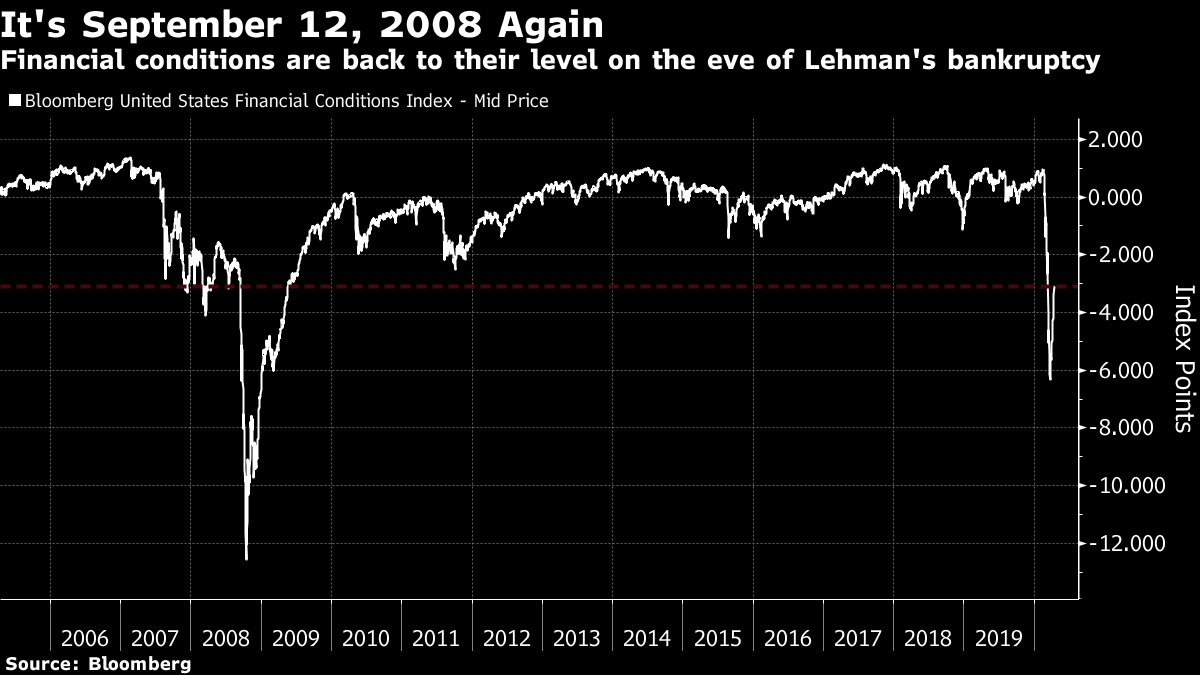

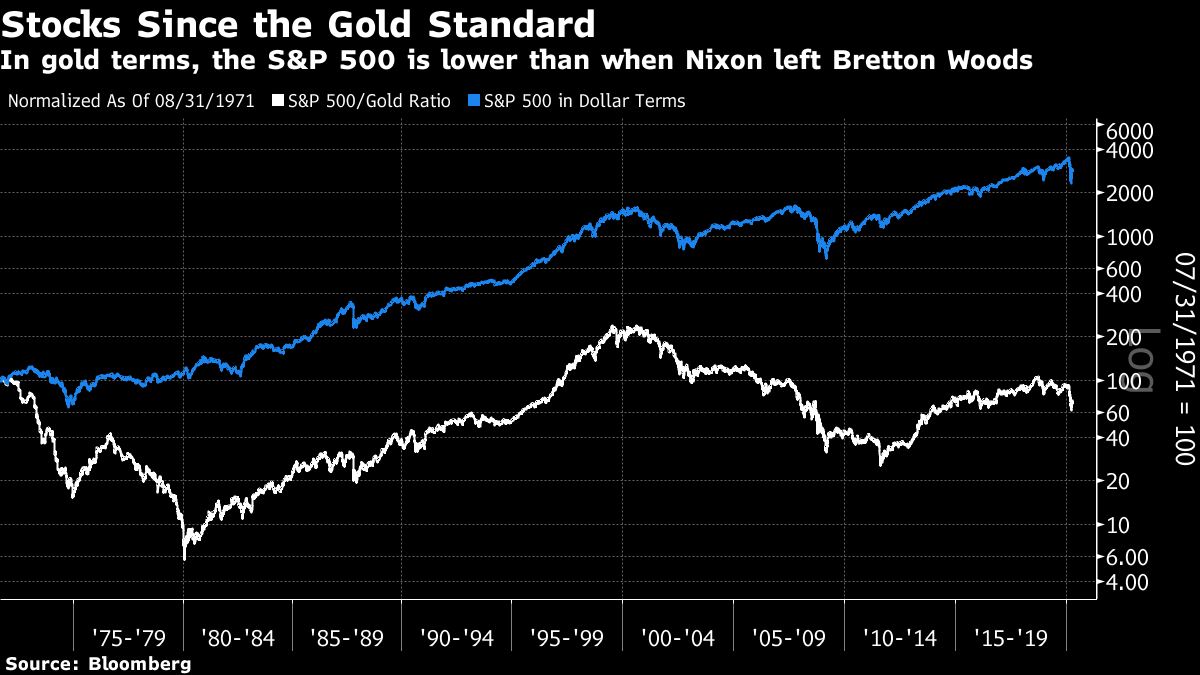

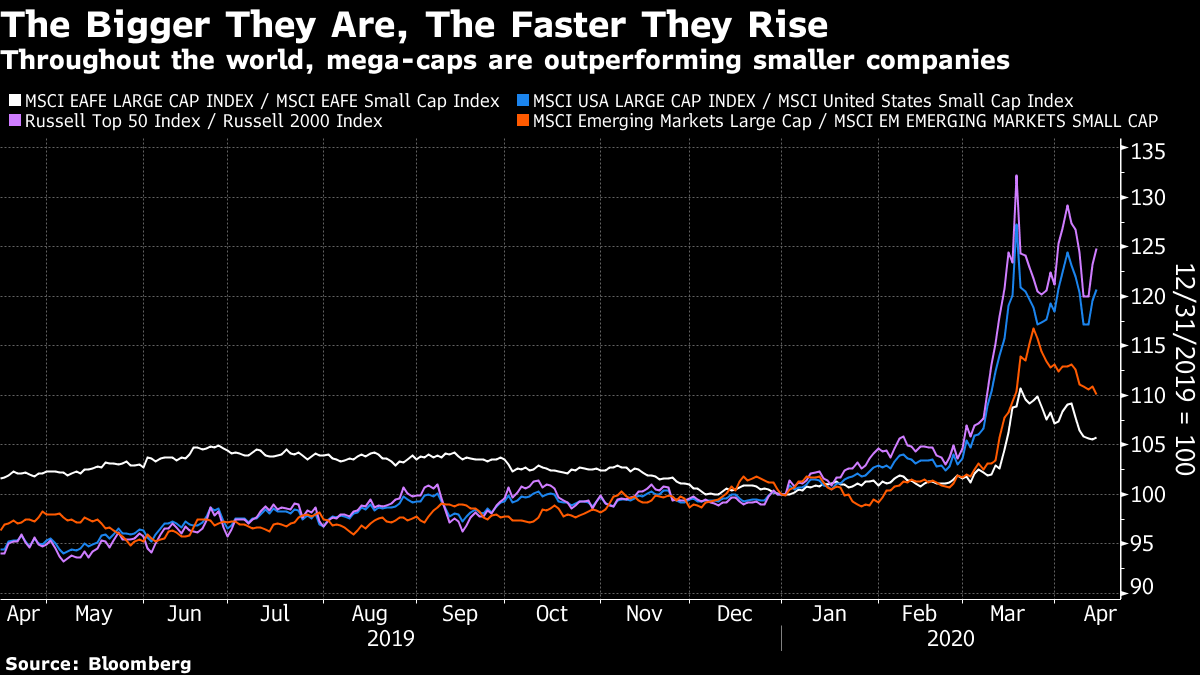

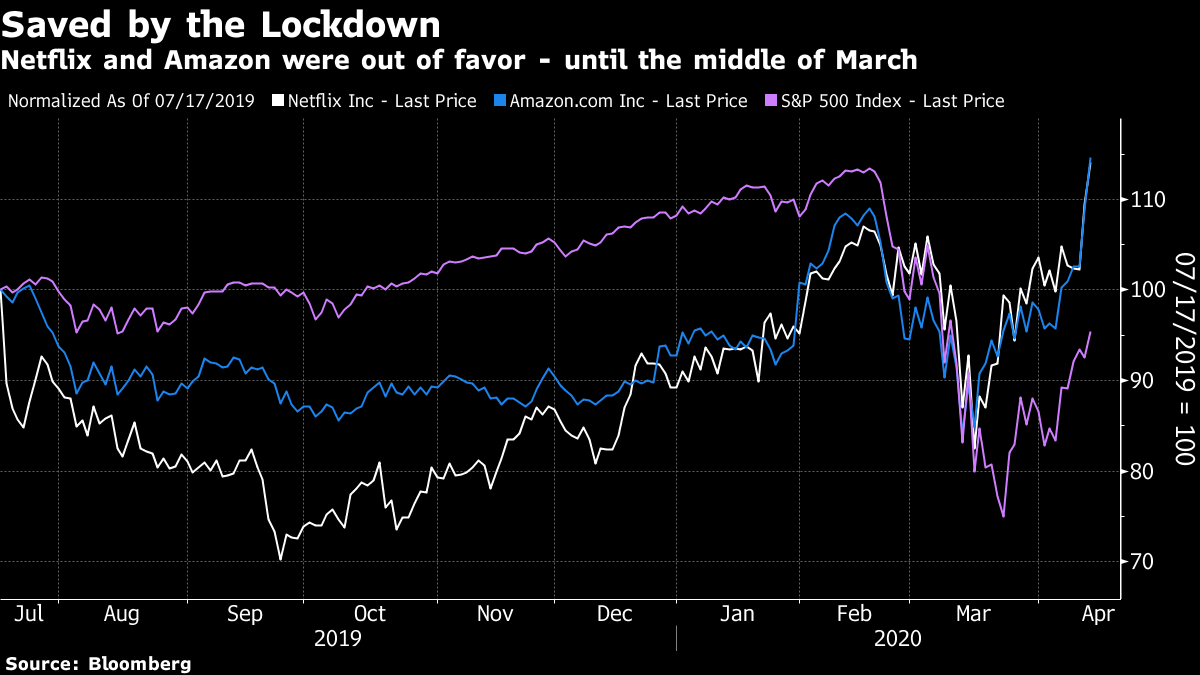

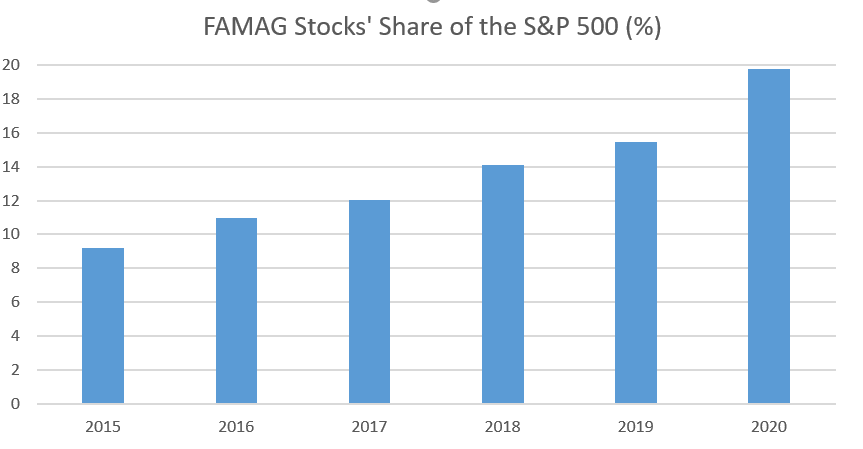

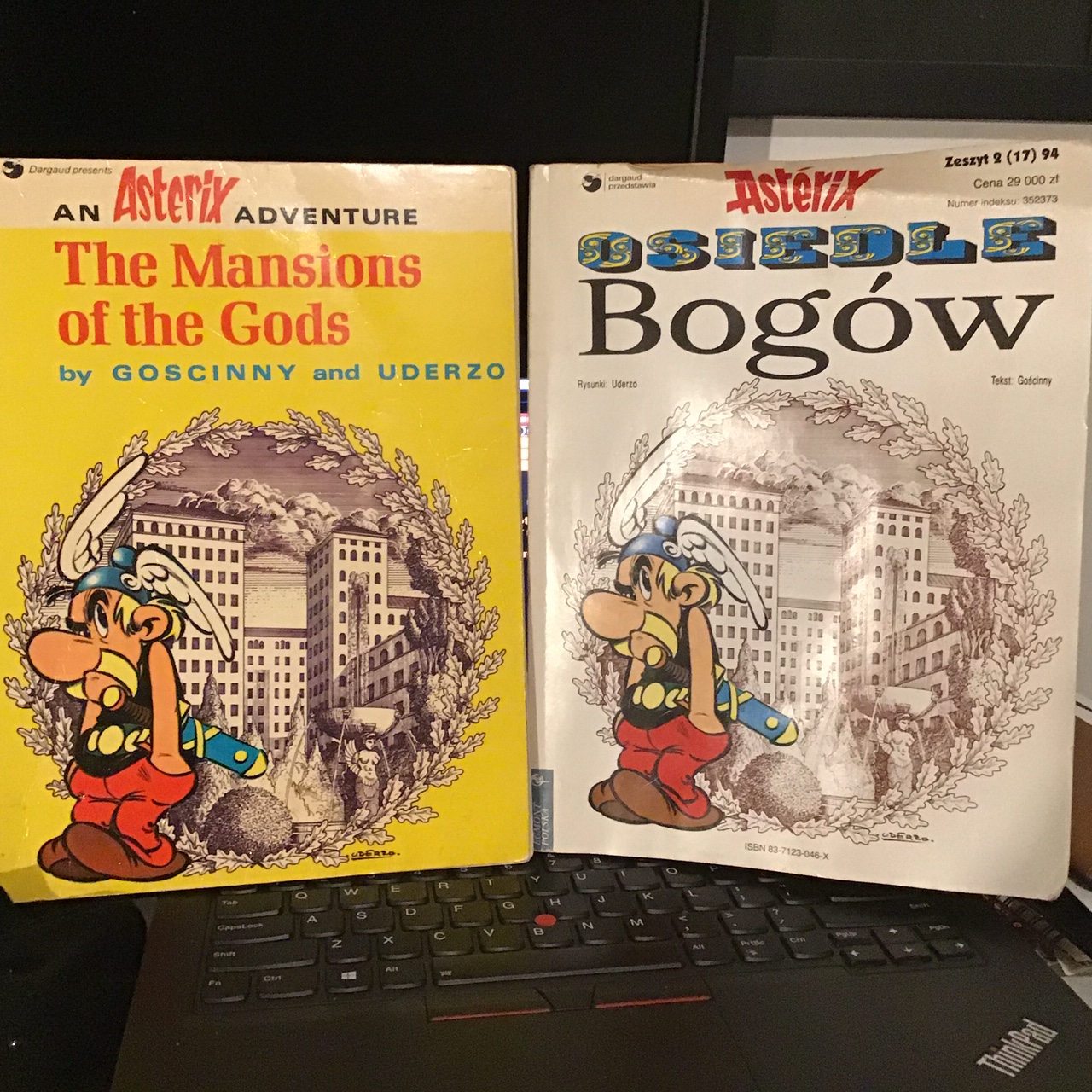

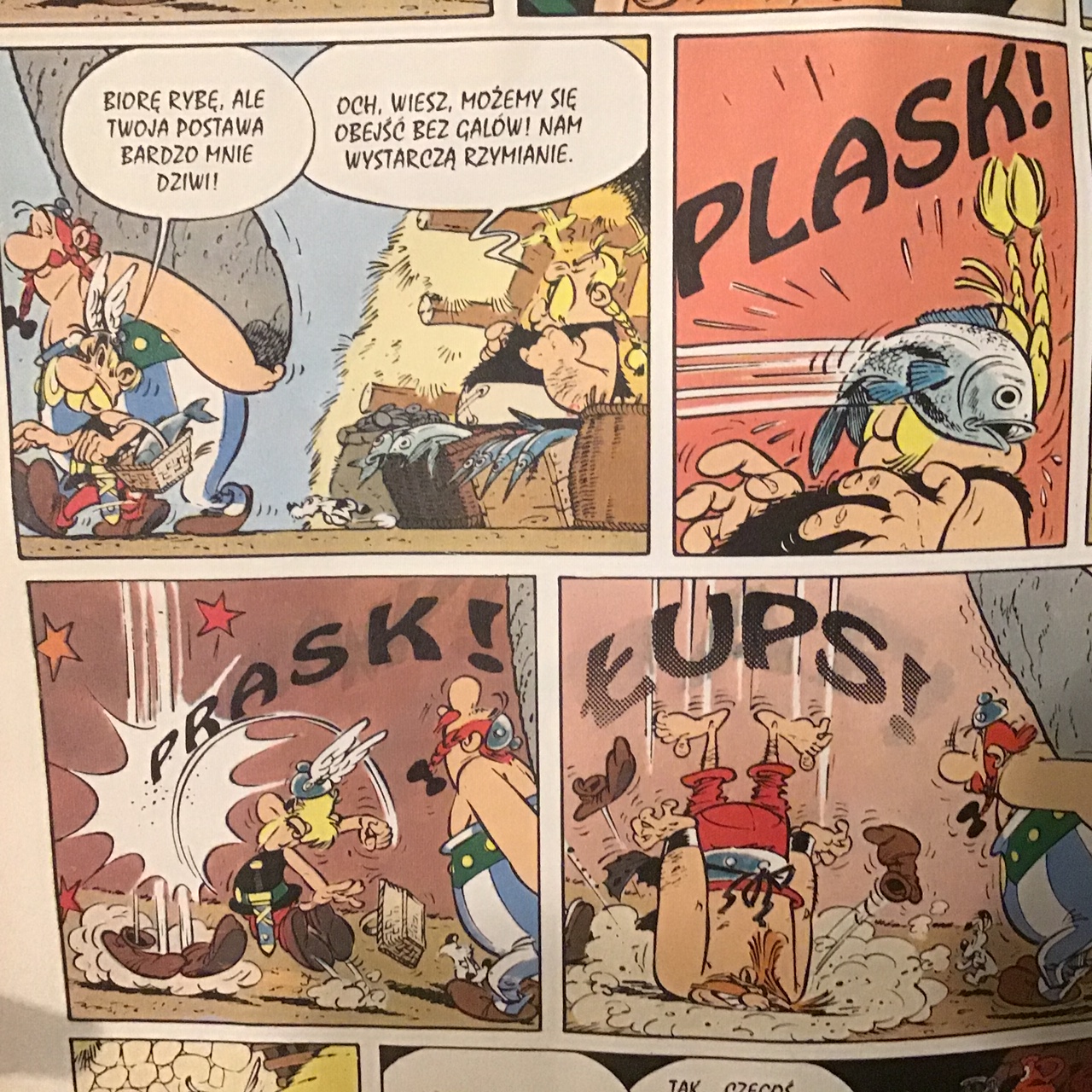

| The stock market, home of optimists everywhere, is doing very well at present. But gold, where pessimists find a home, is doing even better. In dollars, the shiny metal closed on Tuesday at its highest since 2012. The all-time high is in sight, and it has gained more than 60% since its nadir in 2015:  At one point last month, gold was selling off amid denunciations that it had failed as a safe harbor. That was more or less entirely due to its inverse relationship with real yields on bonds. Gold's greatest weakness as an asset is that it pays no income. Hence, when real yields go negative, gold grows much more attractive. As the bond market melted down last month, real 10-year yields briefly touched -0.6%, before gaining more than a full percentage point. They are now back around -0.6%, near an all-time low. As can be seen, gold's fall last month overlapped exactly with the brief rebound in inflation-adjusted yields:  The bond move has been driven more by a shift in inflation expectations than by the underlying yield. Inflation break-evens remain at levels lower than anything in the last 15 years bar the Lehman crisis and the Chinese devaluation of 2015. There's no way gold's rally can be seen as an attempt to hedge against an expected return of inflation:  Meanwhile, the fall in real yields is among many factors that have helped ease financial conditions, which has a lot to do with the stock market's recovery. Both can be attributed in large part to the historic actions by the Federal Reserve. There is much to debate over what the Fed has done (I suspect it is a Faustian bargain), but the Bloomberg U.S. Financial Conditions index, which combines nine separate measures from different markets, shows how powerful the effect has been. Whatever mistakes the Fed has made, it has at least corrected one error from 2008 and gone for broke straight away:  At its lowest, the financial conditions index was at its level from the week immediately after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in September 2008. It is now back to where it was at on the Friday before Lehman went down — which is to say that we are now out of the territory where the entire financial system appeared to be broken. As the financial world had been in serious crisis mode for a year before the Lehman bankruptcy, we cannot say we are out of the woods. And of course it is possible that the Fed has avoided repeating one mistake only to make a new one. A rising gold price is always a disquieting sign. What, meanwhile, does gold tell us about the stock market? I am not a fan of returning to the gold standard, but it is undeniable that the decision by President Richard Nixon to break that link in 1971 had a profound effect on what followed. If we regard gold as the continuing true measure of monetary stability, it suggests that stock markets' gains in the almost 50 years since are almost entirely due to "money illusion," or the erosion of the dollar's buying power. The following chart shows the value of the S&P 500 in dollar terms, and the ratio of the S&P 500 to the gold price, both set to 100 when Nixon left the post-war Bretton Woods agreement:  In gold terms, the stock market was higher than in 1971 for a few years around the top of the dot-com bubble, and again for a few months at the top of the latest bull market. It is now almost 30% below where it was in 1971. To be clear, stocks would still have been a better investment than gold in 1971, because these numbers don't include reinvested dividends. But this exercise suggests that stocks' function as a store of value is largely an artifact of the dollar. The higher gold price also suggests that confidence in the dollar is waning. Actually, Size Is Everything The U.S. stock market has now retraced more than 50% of its losses during the corona-crash. While this is surprising and positive, the composition of the rally is cause for concern. It is ever more dependent on a few large stocks, particularly the mega-corporations that dominate the internet. For one illustration, this chart shows how large-cap companies have performed compared to small-caps in the U.S., the rest of the developed world, and the emerging world, according to the MSCI indexes. In all cases, large-caps have greatly outperformed during the crisis. Mega-caps, represented by Russell's Top 50 index for the U.S., have outperformed particularly. In general, the leadership of the big is a U.S. phenomenon:  It should surprise nobody that this is primarily about the FAANG internet stocks. Initially named for Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Netflix Inc. and Google, the moniker has widened since then. The NYSE Fang+ index also includes Apple Inc., Nvidia Corp., and some of the big Chinese internet names, such as Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. Usually when an index is set up to exploit a popular investing acronym, that suggests it's about to run out of steam. Certainly not this time. This is how the Fang+ index has done compared to FTSE's all-world index since inception in 2014:  The lockdown has given this trend extra juice. In particular, Netflix and Amazon are seen as companies that will unequivocally benefit as a result of our current incarceration. The following chart, which starts with Netflix's poorly received results for last year's second quarter, shows that both companies had been out of favor until the lockdown — and then suddenly turned around:  As I said yesterday, I believe there are reasons to doubt that these two companies really will win in the long term. The bet on them looks over-extended. In the long run, what is perhaps more concerning is the extent to which the entire U.S. market has grown top-heavy. For these purposes, the acronym to worry about is "FAMAG" — Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft Corp., Apple and Google (which these days trades under the name of parent company Alphabet Inc.). These are the five largest companies in the S&P 500 by market cap, and have been for three years (Exxon Mobil Corp. kept Facebook out of the top five in 2017). The following chart shows the combined weight of the five FAMAG stocks in the S&P 500 on this date for each of the last five years:  (I drew it myself on Excel using Bloomberg data — apologies for problems with the graphic software). Their weight has doubled in five years, starting from a level when they were already ensconced as the greatest financial phenomena of the age. Generally, buying the largest stock in the S&P 500 over history has been a bad idea. Such stocks have nowhere to go but down. Just in the last 30 years, General Electric Co. and International Business Machines Corp. both spent a lot of time at number one, as more briefly did Coca-Cola Co. and Cisco Systems Inc. In the case of FAMAG, buying the leading juggernauts, holding them, and waiting for them to extend their lead over everyone else has been the right strategy for at least half a decade. When you buy a stock you are buying a share of its future profits, not its past. Are these companies really going to stay this dominant into the future? A market this narrow suggests that some bad news, or reason to shake confidence in one or more of the FAMAG stocks, could shock the whole market. While confidence in them remains this strong, though, the main index is unlikely to go back to its lows of March. Survival Tip: Magic Potion There is nothing like Asterix to get you through a day of enforced confinement. Last month, I noted that Albert Uderzo, one of the creators of the brilliant comic books about Asterix the Gaul, who sees off Julius Caesar and the Roman army with the aid of magic potion that gives him superhuman strength, had sadly died. I discovered at the time that lots of Asterix fans are subscribed to this email. Some of you even indulge in my old habit of trying to get hold of Asterix books translated into different languages. They rely on wit and satire, but have been remarkably well translated into many languages. I made one mask-clad trip today on an errand. Two blocks from our house, someone has left a wooden bookshelf, which is used as a neighborhood book exchange. Drop books off there, and pick up some others, for free. To my delight, I discovered a copy of Mansions of the Gods, a brilliant satire on the Romans' failed attempt to break the Gauls into submission by putting a new property development around their village, translated into a language I don't have in my collection — Polish:  I speak no Polish, so cannot judge the quality of the translation. But one of the enduring joys of this, which I am glad to say I find almost as amusing now as I did when I was seven, is to compare onomatopoeia in different languages. In English, as we all know, the noise a fish makes when it hits someone's face is "Splatch". And if Asterix should hit you into the air, it will sound like "Schplonk," while when you hit the ground again you will go "Paf!"  I have now at least begun to build my Polish vocabulary. "Splatch," can be translated into Polish as "Plask," when you get hit by Asterix the noise is "Prask!" not "Schplonk!" and of course the Polish for "Paf" is "Lups":  I suspect many weren't looking for Polish onomatopoeia when they subscribed to this newsletter. But few things have helped me more in the last month than the joy of discovering a rain-soaked Polish comic book on a street corner in Uptown Manhattan. If I have a survival tip out of all this, it's that rediscovering what made you happy as a child can be really good for you. Any other tips gratefully accepted. And if anyone out there has any more Asterix books in translation, let me know. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment