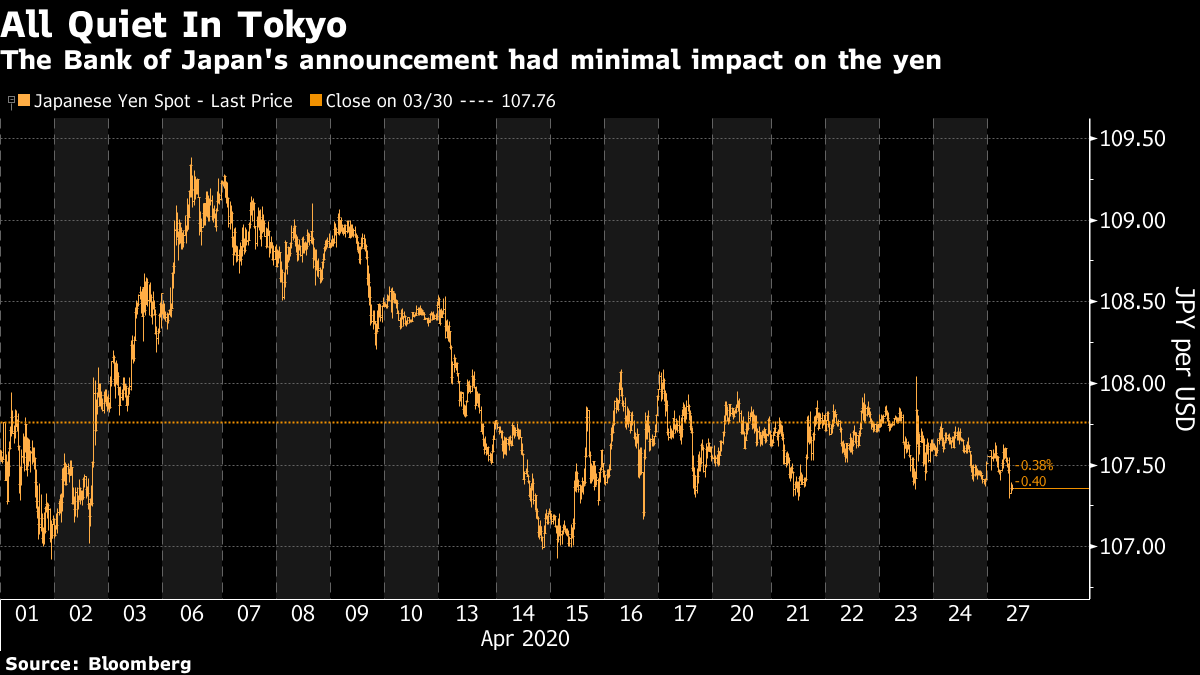

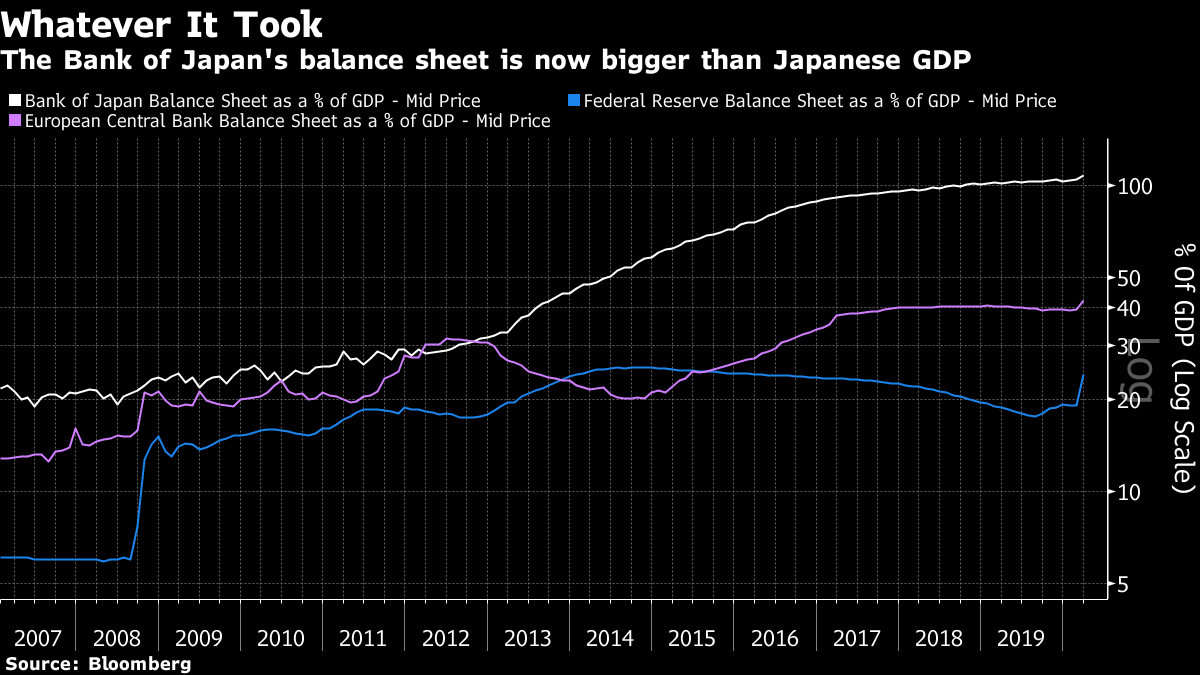

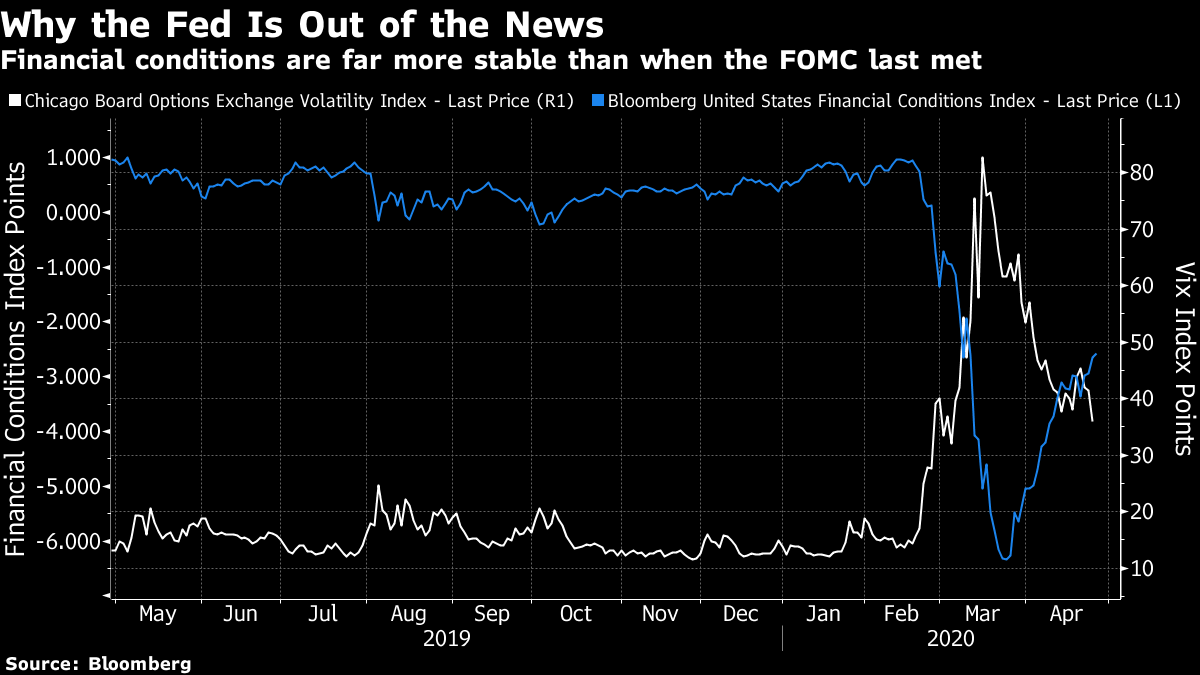

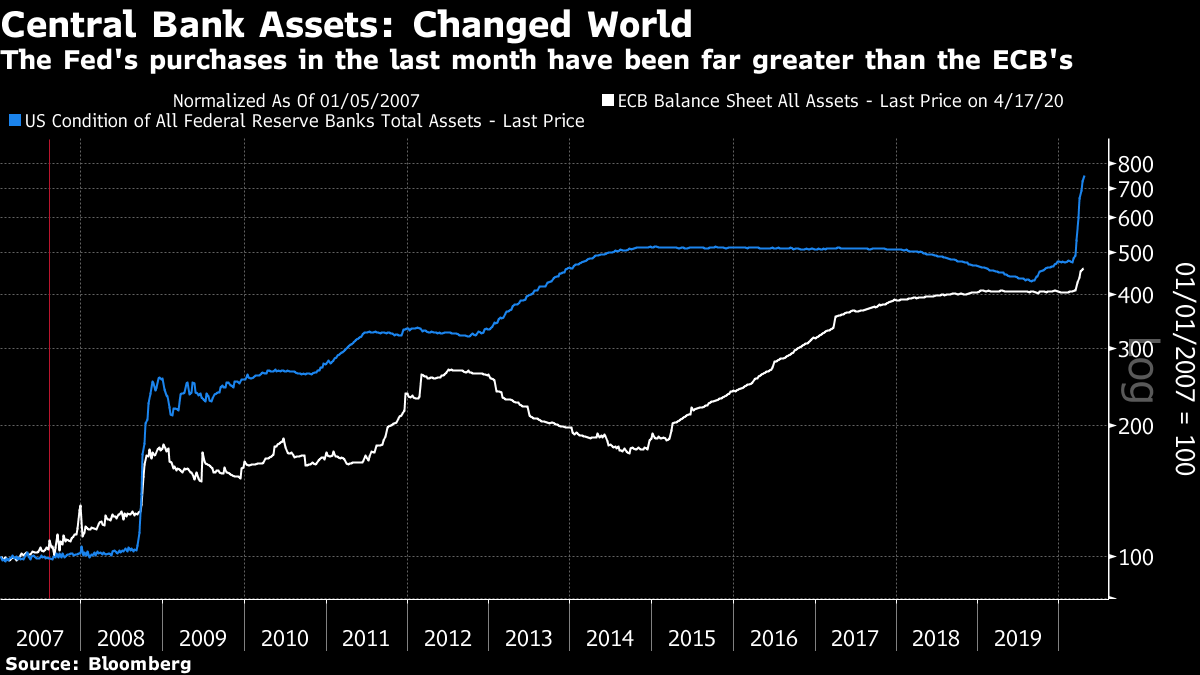

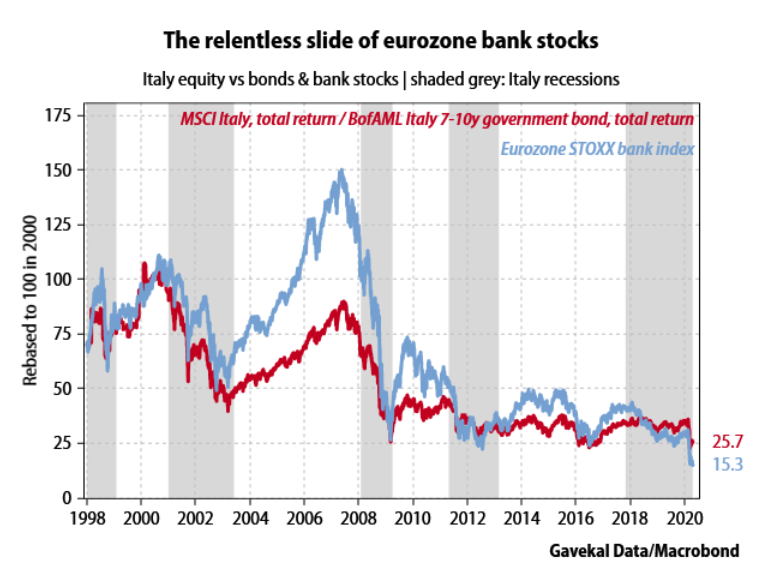

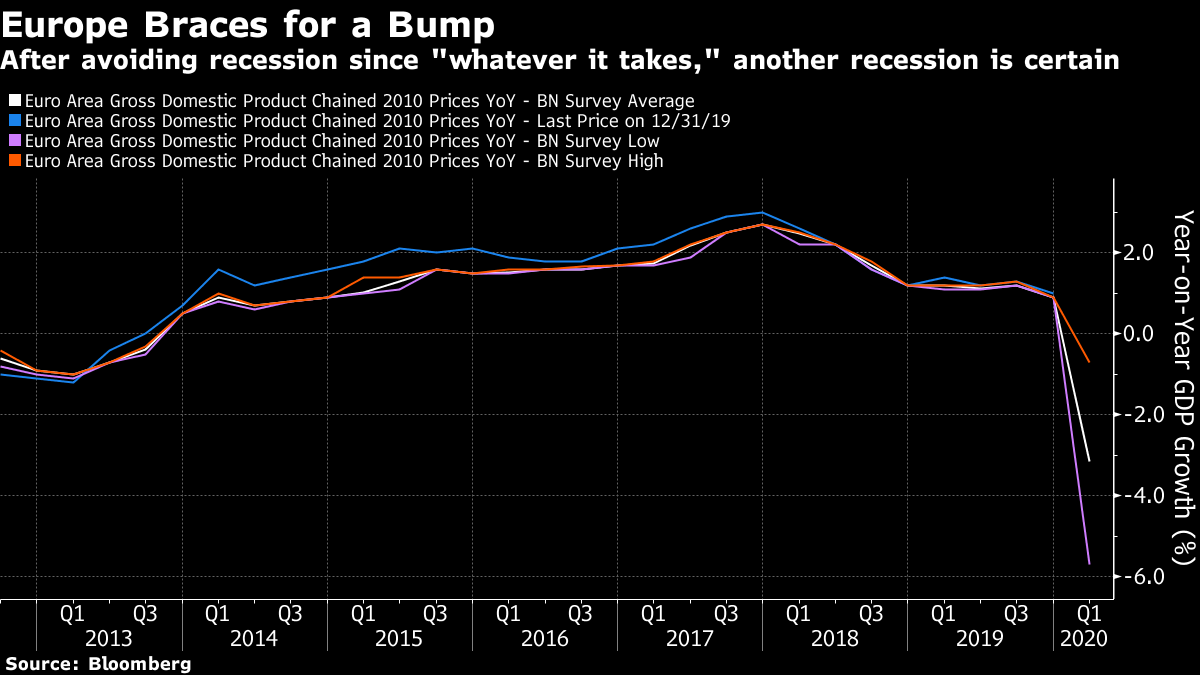

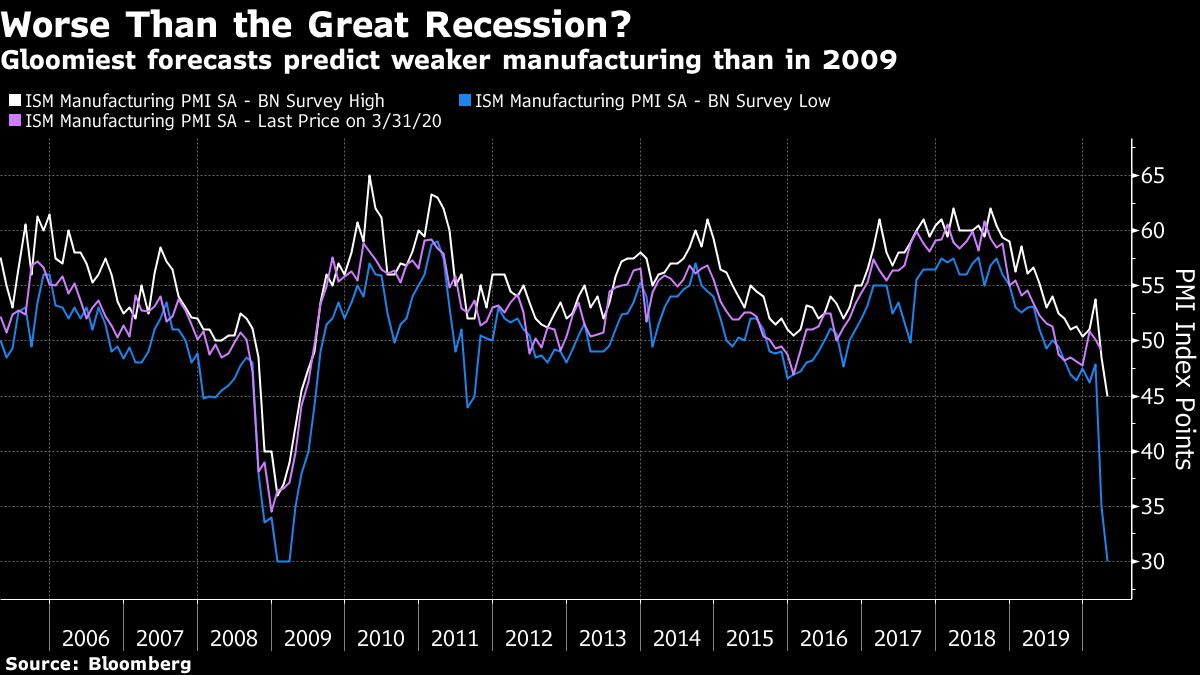

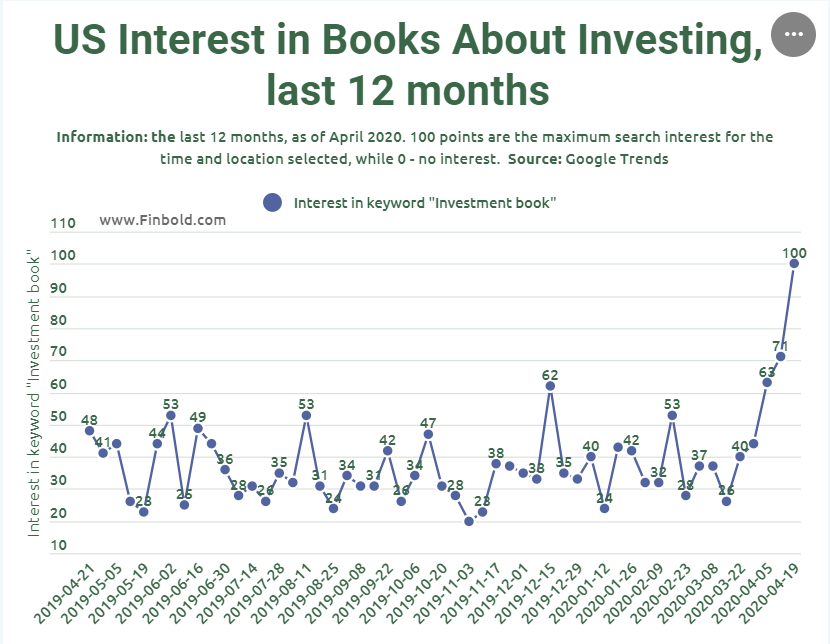

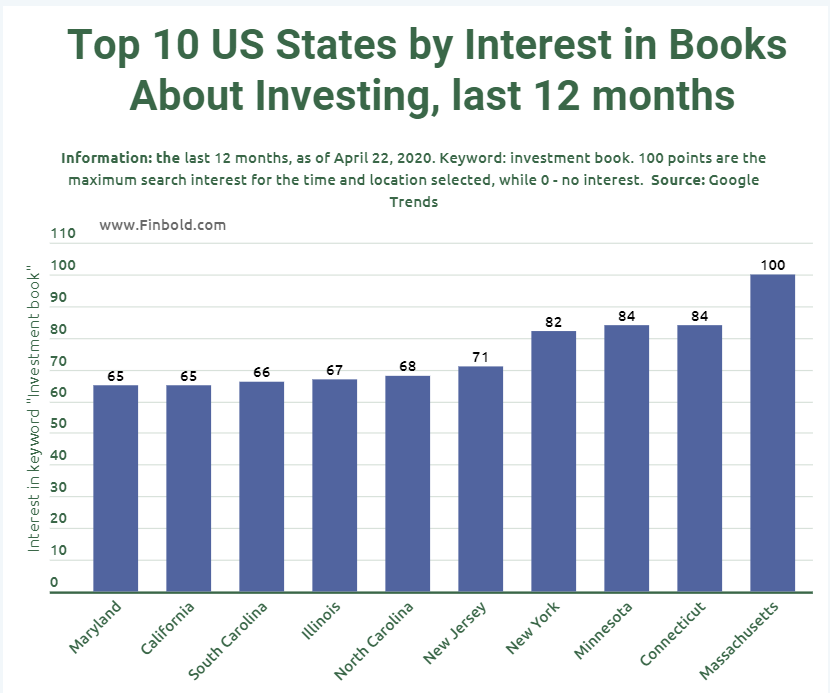

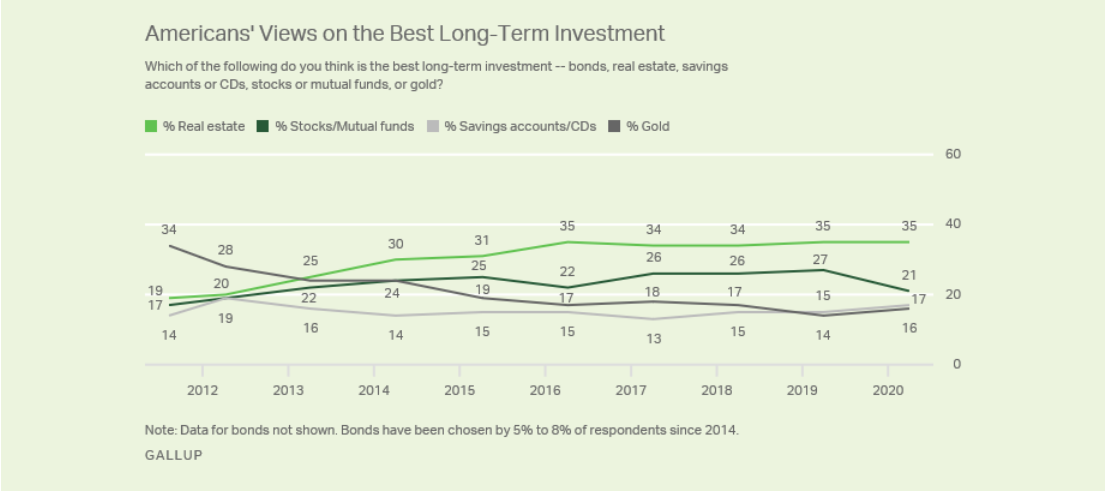

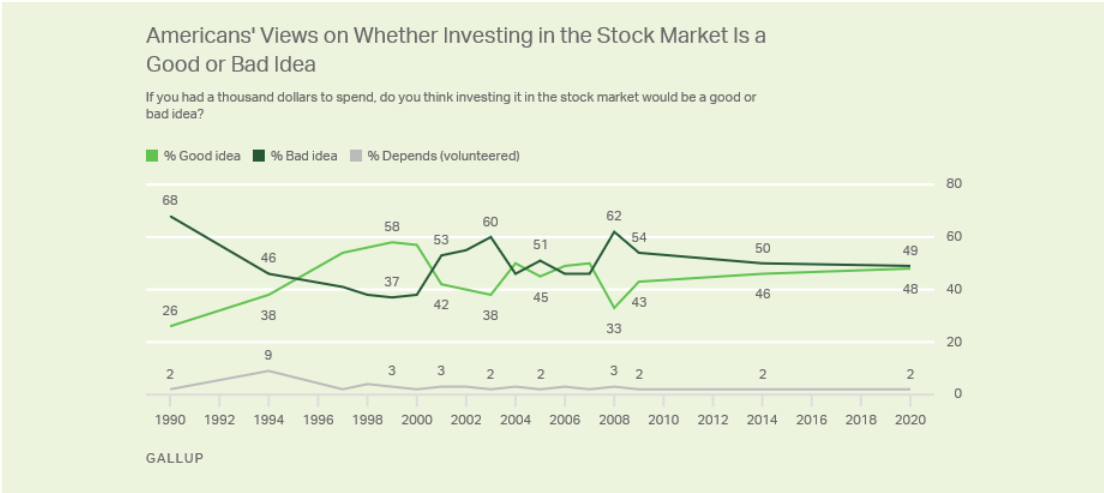

| Normal life hasn't vanished completely. This week brings a reminder of that, with one of those calendar combinations that in normal times would dominate international markets. In quick succession, the world's three biggest central banks — the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan — meet to discuss monetary policy. The BOJ started the week, with the Fed and ECB to follow Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. As Friday is also May Day (which might have some unfortunate resonances this year), we also get the beginning of economic data downloads for April, a month in which Covid-19 effectively closed the economies of western Europe and the U.S. for the duration. The supply manager surveys due at the end of the week will begin to let us know how much China's economy has managed to rebuild; and should also give the gravest evidence yet of the scale of the economic hit to the West. On top of that, we have the busiest week of the first-quarter earnings season. All of this will take a back seat to the intensifying debate over how quickly to withdraw the social distancing measures that appear to have saved the world from a public health catastrophe, but at the expense of a possible economic catastrophe. It is never safe to ignore central bank announcements altogether, but this week is likely to be underwhelming. The BOJ's announcement, which centered on removing an upper limit to its purchases of bonds, looked like a virtually infinite promise of action. But this had been expected. As a result, reaction in the currency market was scarcely visible. This is the yen against the dollar over the last month, with the BOJ announcement coming at the end:  The BOJ has long since been pressing against the limits of what a central bank can do. Fiscal policy is already beginning to pick up in Japan, which is just as well, as the BOJ's balance sheet is now bigger than Japan's GDP. It has been by far the most active of the big three central banks:  There is possibly, and very unusually, even less pressure on the Fed. That's because the U.S. central bank has already taken such drastic action that market conditions have calmed significantly:  That doesn't mean the Fed has nothing to discuss. It is working so closely with the Treasury Department as to bring its long-term independence into doubt. Having expanded its buying operations into high-yield bonds, the Fed also has to face the issue of whether to follow this policy to its logical conclusion and try buying stocks. But the greatest focus for now is, rightly, on Congress, which has control of fiscal policy. The greatest interest will come last with the ECB. Since the day in August 2007 when the ECB intervened in the frozen European money markets, subsequently dubbed "the day the world changed" by executives of Northern Rock, the British savings bank that suffered a catastrophic run the following month, the world has changed a lot more. A look at the scale of the ECB's balance sheet shows that it has twice since tried to normalize, and reduce its assets, only to be forced into a U-turn. Proportionately, it is yet to take action anything like as aggressive as the Fed's:  The ECB faces two problems that the other central banks don't have. One is the risk to the integrity of the euro zone. The other is the weakness of the European banking system. These problems are linked, as the euro zone remains far more reliant on bank finance than the U.S., where the bond market is more important. The following chart, produced by Charles Gave of Gavekal, demonstrates the problem neatly. Euro-zone bank shares have steadily ebbed away since the crisis, roughly in line with the ratio of Italian stocks to bonds. When Italian stocks look that bad, it means the economy is weak, which puts further pressure on Italian banks, which puts pressure on all European banks. Italy, as the largest economy on the euro zone's southern periphery, is also the best stand-in for the risk that the zone falls apart:  Fiscal policy is supposed to pick up the pace. But last week's conference of European leaders failed to reach agreement on any comprehensive plan for shared debt-raising through so-called "coronabonds," which would have been a major step toward a common fiscal policy that the northern euro-zone nations don't want. That leaves the ECB to try to cajole governments into taking fiscal action, while also averting disaster while they wait. Even more awkwardly for ECB President Christine Lagarde and her colleagues, their meeting will come immediately after the first print of euro-zone GDP for the first quarter. As the chart shows, forecasts, as reported to Bloomberg, are all over the place. But everyone agrees that the first quarter was very, very bad:  So the ECB is under greater pressure to do something. Confidence in the banking sector is ebbing away worryingly. But it isn't at all obvious what it can do. On May day, U.S. manufacturing PMI data should give the first decent indication on the extent of the viral hit to U.S. industry. Again, the estimates are unprecedentedly wide. Everyone agrees the outcome will be terrible. Some are braced for something worse even than the depths of the Great Recession:  That is what the central banks will have to cover this week. In better times, we would care about it far more. Latin America's Inverse Boom The "boom" in Latin America used to refer to literature — the wave of magical realist novelists like Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Mario Vargas Llosa, who put the region on the map in the 1960s and 1970s. Now, the boom is real but in no way magical; it is suffering the financial effects of the coronavirus like no other. Latin America has a tendency to move in long financial waves. Twenty years ago, the continent saw a series of startling events — the ejection of the Institutional Revolutionary Party after 71 years in power in Mexico; the failed coup against Hugo Chavez in Venezuela; the default and devaluation of Argentina after years of a pegging its currency to the dollar; and, most importantly, the election of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, a former union leader, as Brazil's first leftist president. Lula's election proved to be the catalyst for an extraordinary period of outperformance by Latin American stocks compared to the rest of the world. But that peaked a decade ago and, as the chart shows, the region's underperformance so far this year has been spectacular. All its outperformance of the all-world index in the last 20 years is now erased.  Why? The coronavirus so far isn't reversing financial trends. But, just as it is most dangerous to humans who are already vulnerable in some way, it has a way of attacking where there is weakness. At the outset of the year, the region already appeared to be lapsing into secular stagnation. Even success stories such as Colombia seemed stymied. With less demand for commodities, or other exports, the region's inability to generate its own growth becomes all the more painfully apparent. Covid-19 also attacks perceived weak leadership. The presidents elected by Brazil and Mexico in 2018, the populist right-winger Jair Bolsonaro and the populist left-winger Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador respectively, have both taken an oddly relaxed attitude to the pandemic, which has shaken investors' confidence. At times like this, Latin America acts like a derivative of the rest of the world. When the Fed surprises by hiking interest rates, as happened in 1994, it is Latin America, and not the U.S., that suffers a wave of devaluation and default crises. When Chinese demand sends commodity prices through the roof, Latin American assets do best of all. It might just work that way again. But with the mandates of Bolsonaro and Lopez Obrador still having many years to run, there will be no clear political catalyst, as there was at the beginning of the last boom. And the stagnation in Latin America's economies will make any rebound much less impressive than the one that started after Lula's election. Survival Tips Correlation doesn't prove causation. That's a shame, because we're reaching the anniversary of the Authers' Notes Bloomberg book club, which held its first online chat last April. Since we launched, the financial news aggregation site Finbold.com finds that interest in investment books on Google Trends has more than doubled, rising by 159%.  Greatest interest was in Massachusetts, birthplace of the mutual fund:  I find it a little surprising that people want to read books about investment when they might be psychologically more in need of something escapist. Brushing up on investment at a time like this also suggests a kind of contrarianism that Americans as a whole do not have. The latest Gallup poll finds that stocks are lagging ever further behind real estate as the perceived best long-term investment — even though it's little more than a decade since the last real estate crash. And the bull market in gold hasn't dissuaded people from ranking it behind even cash:  Much of my life is spent immersed in a debate between bulls pushing stocks, and bears pushing gold. Most Americans, plainly, live in a different world and see the choice as between investing in bricks and mortar or putting their money in the bank. A majority of Americans still think investing in stocks isn't a good idea, even after what many regard as the longest bull market for stocks in history:  Confidence appears never to have recovered from the dot-com bust. So I suppose it is a good thing that interest in investment is picking up. Finbold also offers that wonderful thing, a list of books. I don't agree with all of their top 15, in part because I haven't read a number of them. I suggested five books to read while in isolation last month; I'll happily come up with another five. As for the book club, we felt it was a necessary casualty of Covid-19. The club is in abeyance for now. Still, online discussions about books can be a great way to maintain sanity under these conditions. If we resume, maybe we can raise interest in investment books by another 150%. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment