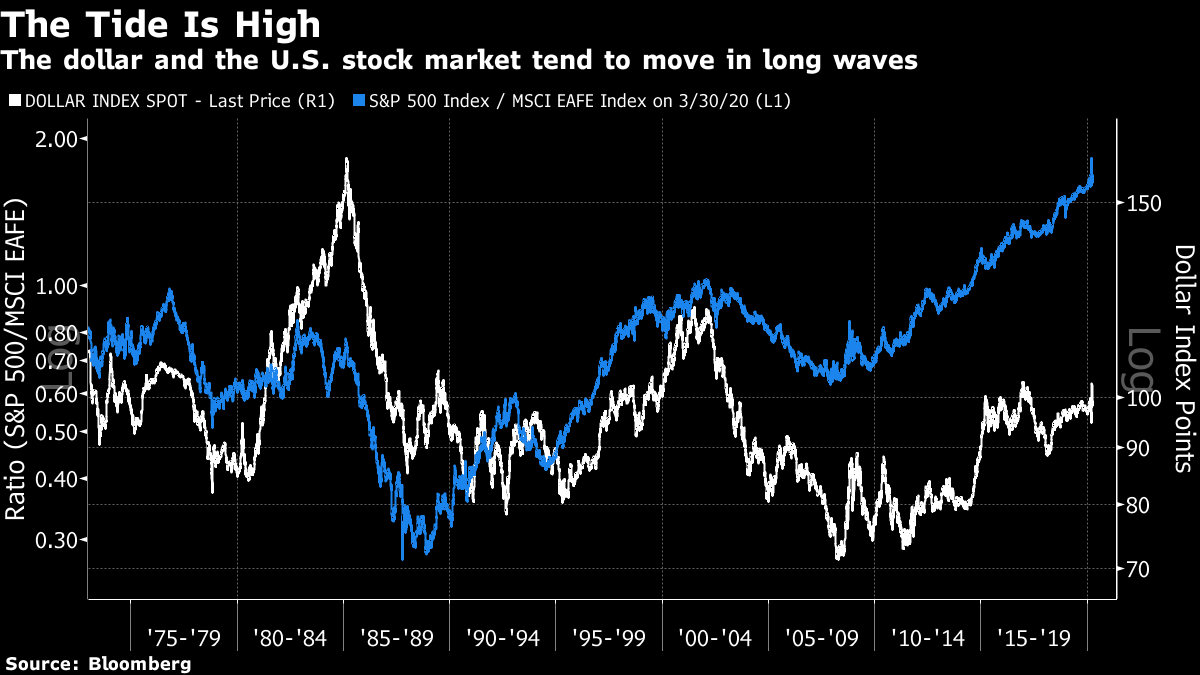

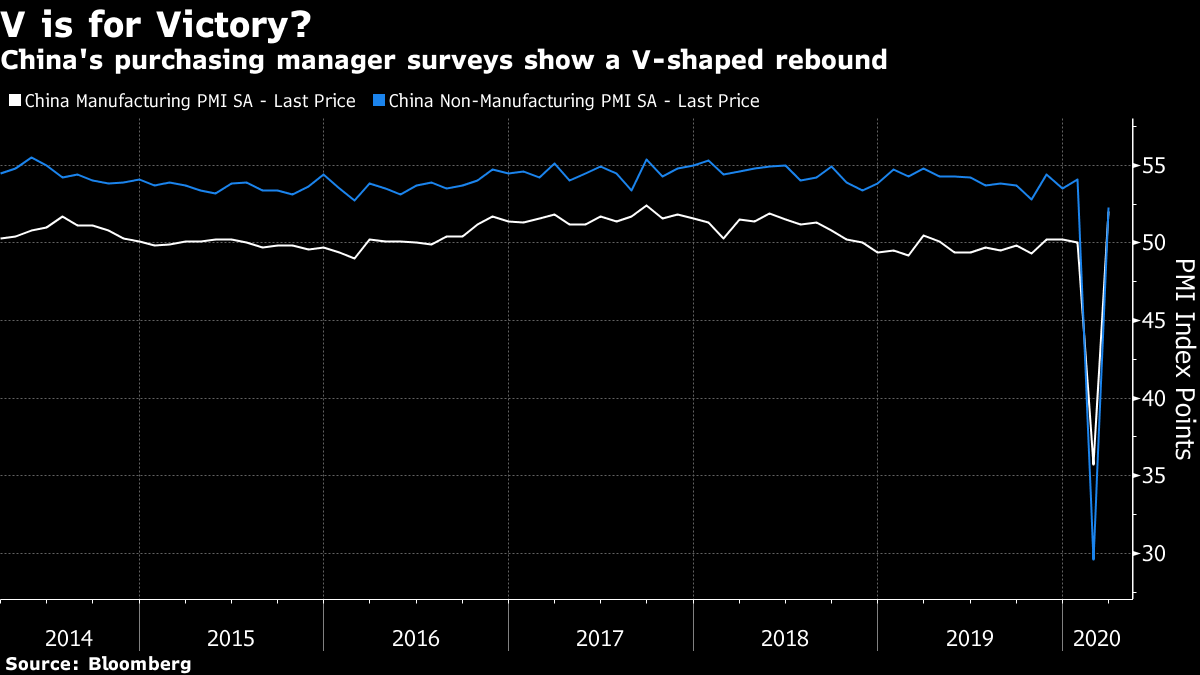

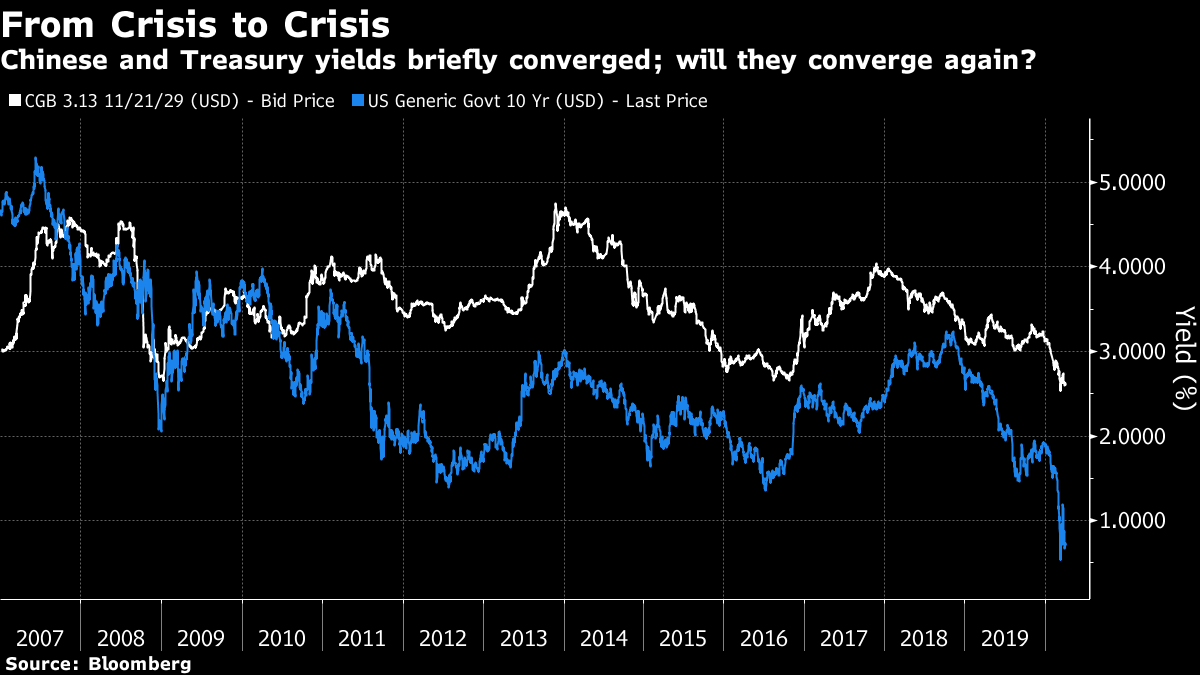

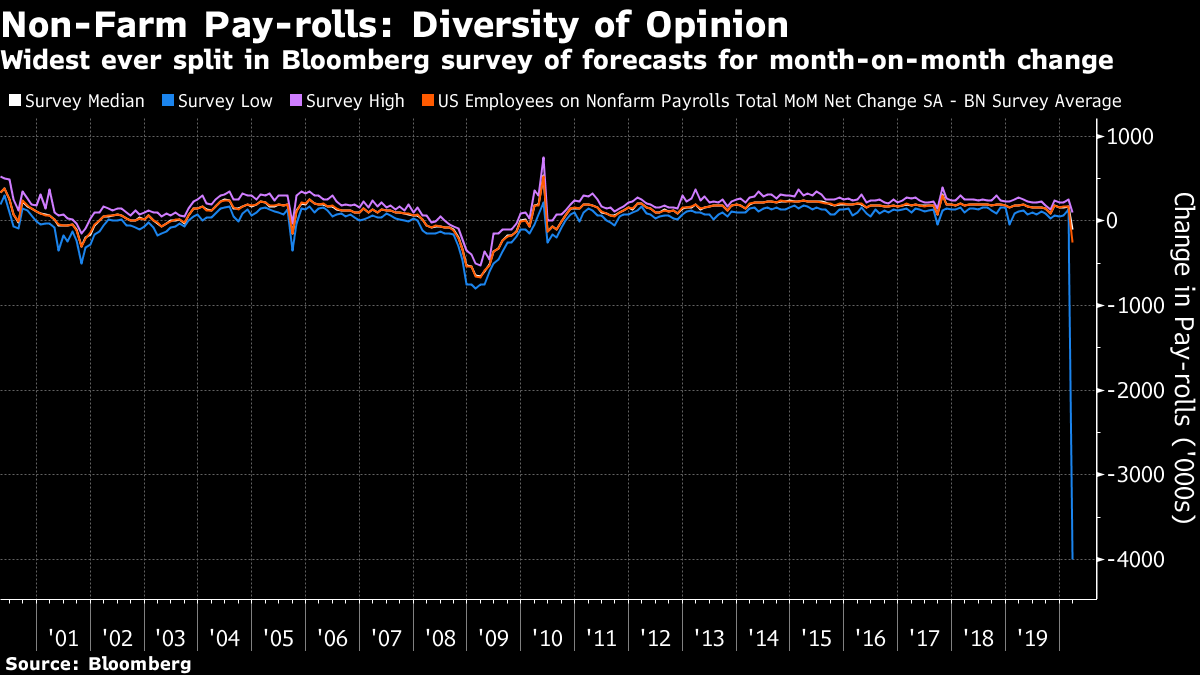

A Shot Heard Around the World In the summer of 1914, as the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo ushered in the First World War, the U.S. dollar was quoted and convertible in far fewer international markets than was the contemporary Austro-Hungarian krone. The moral: huge global events can mean swift and sudden change to the financial order. The coronavirus crisis should still wreak far less human damage than the Great War, which precipitated the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but the shock to the global system may be comparably great. According to Michael Howell of London's CrossBorder Capital Ltd., this is reason to prepare ourselves for another change of global financial leadership. After a century in which the financial world orbited around the dollar, he believes that we are at the beginning of the Chinese century. If this sounds outlandish, remember that almost everyone suddenly seems to agree life after the coronavirus will be different. This crisis will change us. The disagreement is over exactly what it will change us into. When it comes to which nation will benefit the most, two camps are emerging. The first holds that the U.S. is already using its immense fiscal and monetary firepower and this will ensure it comes out on top, just as after the last great crisis. A second camp holds that it will lead to a changing of the guard. In 2008 it fell to China to "save the world" with an enormous fiscal stimulus. It did the trick, but China has been struggling with the after-effects for the past decade. This time the job falls to the U.S. The Fed's balance sheet is already the biggest it has ever been. The money Congress is preparing to throw at the problem will come to about a tenth of GDP. Howell contends that, like China a decade ago, the chances are that it will buckle under the challenge. Both camps need to be taken seriously. Today, I am only going to look at the belief that China, where the virus originated, will "win" this crisis — much as the U.S., where the subprime crisis started, "won" the last one. The detail of the argument can be found in a new book by Howell called "Capital Wars." First, the dollar tends to move in long waves, taking the relative performance of the U.S. stock market with it. The dollar has been on an upward trend since 2011 (with occasional interruptions), while the S&P 500 has massively and consistently outperformed the MSCI EAFE index, covering the rest of the developed world:  This looks like the kind of crescendo that signals a peak. The catalyst for a reversal is the coronavirus. If this comes to pass, not all is disastrous. During the dollar weakness from 2000 until the 2008 crisis, commodity prices boomed, taking emerging market assets with them. The total value of Europe's stock exchanges even briefly exceeded that of the U.S. And U.S. assets themselves performed well for much of the period. To support the notion of a weakening dollar, note that the Fed's intervention in the past few weeks has matched the level of its intervention in late 2008:  The Fed will have little alternative but to carry on. Meanwhile, the People's Bank of China has been surprisingly reserved. It has eased its reverse repo rate to relieve some pressure on banks, and plenty of debt overhang problems remain, but it doesn't look over-extended. As Howell puts it: "A lot of the instability is that China is leaning too heavily on the dollar system and the dollar can't cope with it." Since the last crisis, huge cash piles have built up in sovereign wealth funds, and in the foreign exchange reserves of Asian central banks, while U.S. companies are also sitting on large cash holdings. All of this adds to the demand for safe assets denominated in dollars, and there aren't enough to go around. Under the pressure of the crisis, this has shown up in an epic collapse of Treasury yields. Safe dollar-denominated assets are much more important to the global system than they used to be because banks are less important. What matters now is the ability to use safe assets as collateral. Without them, it grows far harder to refinance debt, no matter how low the interest rate. That opens the chance that the world will be forced to look for a different anchor currency. Then there's the issue of a post-virus recovery. Having led the world into the slowdown, China has the advantage of leading it out. Its purchasing manager indexes for March, just released, show a "V-shaped" recovery, with both manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors back above the level of 50 that signals the difference between recession and expansion. This isn't quite as impressive as it looks; all managers are asked whether things are getting better, worse, or staying the same, and it would have been alarming if they hadn't shown an improvement. But it still suggests that China might pull off a decent economic recovery:  We now await the outcome in the U.S. The longer it takes to draw a line under the problem and restart the economy, the greater the pressure on the dollar, and the greater the pressure on public finances. A longer lockdown will mean extra debt issuance, which will put pressure on bond yields. Howell points out that the most important number in the global economy tends to be the "price of the dominant economy's debt." This has been Treasuries for generations but "we should be closely watching the yield spread between U.S. and Chinese government bonds. If our fears are correct, this looks set to narrow as economic power shifts from West to East."  Put differently, this is a call that the U.S. is about to lose its "exorbitant privilege" of having the world's reserve currency. This has kept its funding costs low and enabled it to buy foreign assets cheaply. "This mantle may be passing to China," says Howell. Such predictions have been made before, and failed miserably to come true. There is at least a clear reason why it might be different this time: the coronavirus. Bracing for Data This is the last day of March, so the rest of the week will be occupied by the splurge of economic data that greets the start of each month, followed in another week or so by corporate earnings announcements for the first quarter. Whether a company profit, or a macro number, is better or worse than expected won't tell us much. That is because, with only the very slightest of exaggerations, nobody knows what to expect. Non-farm payrolls data for the U.S. are due Friday. This graph shows the median forecast as reported to Bloomberg on the eve of the release, along with the highest and lowest estimates on each occasion. It is a logical necessity that most people will be surprised by the data:  As it's hard to read the numbers from the chart, the average forecast is for a fall of 252,000; the median is a fall of 100,000, the most optimistic is a gain of 100,000, and the most pessimistic is a loss of 4 million. Take your pick. When it comes to earnings, the situation is so confused that analysts are reluctant to revise estimates. This may reflect the justified fear that any assumptions about economic conditions will be garbage.

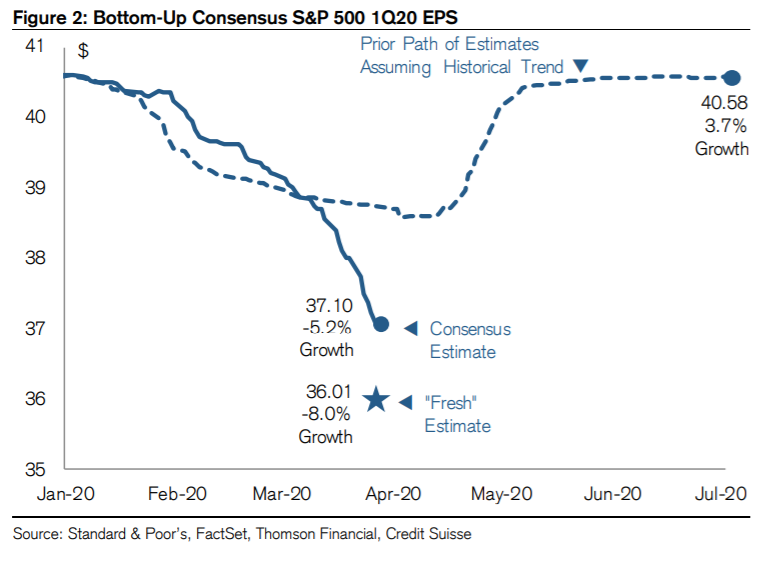

Jonathan Golub, chief U.S. equity strategist at Credit Suisse Group AG, is keeping a handy running total of the official consensus estimates, compared with "fresh" forecasts published in the last week. Estimates are prone to come down anyway in the weeks before the announcement as investor relations people try to lower the expectations bar. This is what has happened to estimates for the quarter about to end. It is drastically more than earnings management:

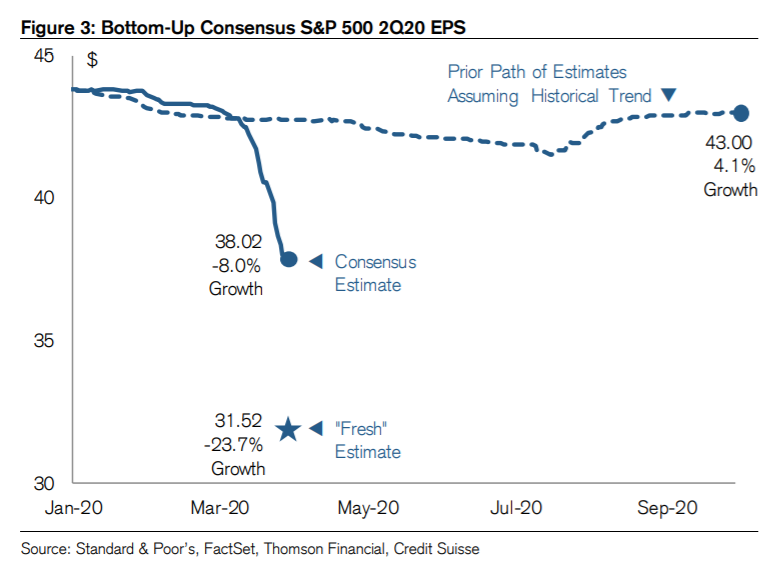

As only 17% of analysts have adjusted their numbers in the last seven business days, the official consensus is probably very stale by now. Now, here is the same exercise for the quarter about to start:  Those who in the past week have tried to put an estimate on the damage to come in the next quarter think that we should brace for a drop of 23.7%. Depending on the course the virus takes over the next three months, that number could change a lot in either direction. For now, the point to grasp is that markets are effectively trading without any notional numbers at all. Don't expect volatility to go away for a while. Survival Tips Podcasting was all the rage even before many of us found out what self-isolation was like. Now, podcasts seem like a life line — a human voice to keep you sane, the ability to discuss something in detail, all without the nasty headache and pain behind the eyes that comes with hours of binge-watching. We all have our favorites, and I loyally think you should listen to all Bloomberg podcasts, as well as offerings from treasured former colleagues such as The Indicator and Behind the Money. But for now I want to recommend a great British institution that has made the seamless transition from being broadcast over the "wireless" on the "BBC Home Service" to a great podcast: Desert Island Discs. For non-Britons, this show has been running since 1942. In each of the 2,252 episodes, the guest has to name the eight records they would take with them if they were shipwrecked on a desert island. In the course of 45 minutes, they talk about their life, explain why the music they are choosing means so much, and at the end nominate one luxury and one book they would take with them. The BBC has made its entire archive available. Guests range from Alfred Hitchock in 1959, to musicians such as John Cale and David Byrne, to politicians and even people I write about such as Mariana Mazzucato or Daniel Kahneman. The website lists every guest's eight records, and the one they would keep if they had to surrender the other seven. It's a seductive format. Your chances of finding things that will keep you entertained for hours on end are roughly 100%. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment