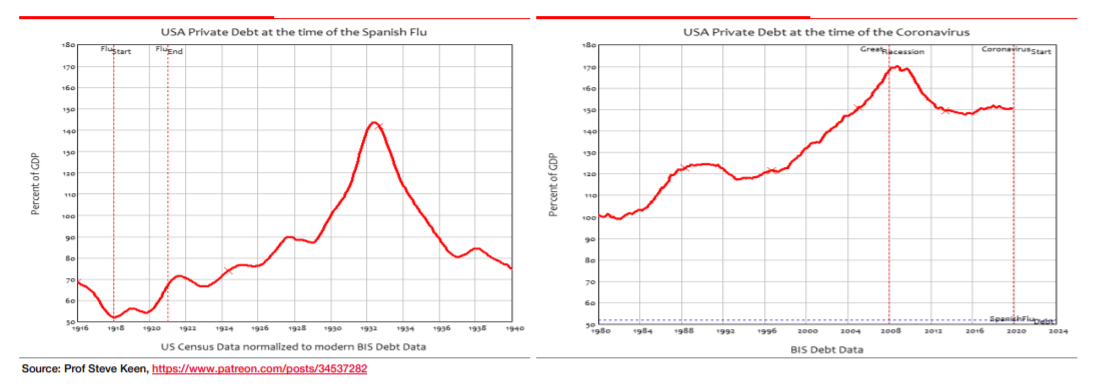

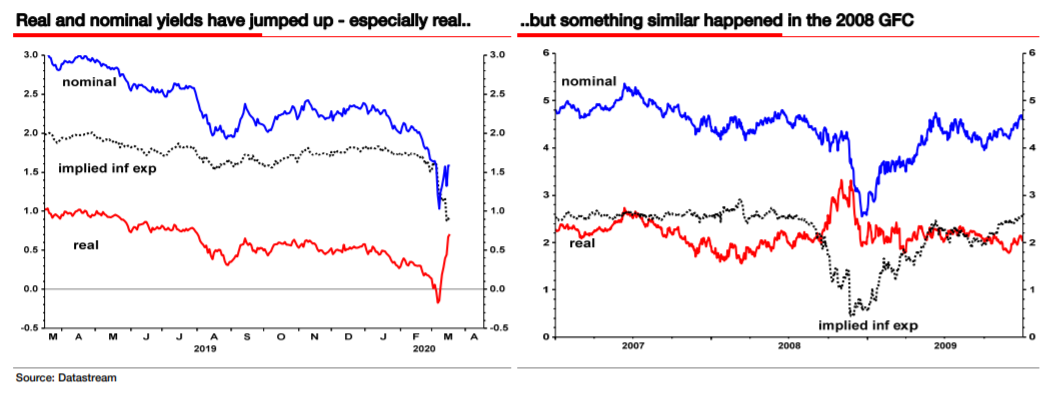

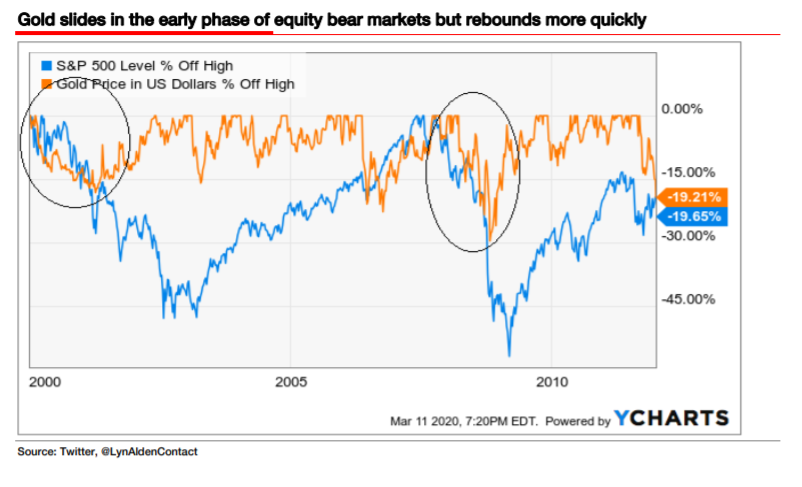

| Is the ice about to melt? For a decade many stubborn bears have refused to accept the long-standing bull market in U.S. stocks. Now they are readying for the moment when they at last switch and recommend buying. As "perma-bears" have a bad press, let me offer two charts to show that their ideas aren't so ridiculous. First of all, the great bull market since 2009 is a strictly American phenomenon. Stock indexes for the rest of the world have recently dropped below where they were at the beginning of 2000 — the last two decades have looked like the protracted range-trading that bears expected after the dot-com bubble burst, and not like a bull market at all:  Further, the bears also — quite logically — expected a bull market in bonds. That we have had in spades. The long-term downward trend in 10-year Treasury yields has appeared to be interrupted on several occasions, and plenty of people were prepared to call a new secular bear market in bonds a couple of years ago. But the downward trend persists, and is one of the most remarkably reliable phenomena in modern finance:  So, the argument goes, we should avoid the distraction of the great performance by American stocks in the post-crisis decade, and look at the message coming from bond markets the world over, and from equity markets outside the U.S. These add up to what Albert Edwards, one of the most famous "perma-bears" and the current chief investment strategist for Societe Generale SA in London, dubs an "Ice Age." Following Japan, the idea is that the world will sink slowly but steadily into a deflationary slump. Bond yields fall ever further, but this isn't good news for stocks, because these are a symptom of a deflationary environment, or "Ice Age," that kills opportunities for equities to make money. Europe has joined Japan in its own Ice Age over the last decade, but defiant action by the Federal Reserve and — even bears should admit — a few remarkably successful American companies kept things warm in the U.S. Until, suddenly over the last month, bond yields dove to fresh lows, and stocks fell into a bear market. Many will say that this doesn't constitute vindication for Edwards and his team. Indeed, Edwards doesn't deny that his call proved way too early — and that on Wall Street or in the City, that is the same thing as being wrong. Buying the U.S. stock market on March 9, 2009, and holding it until Feb. 19 of this year (still only a month ago), would have been a better call. He also has to confront the widespread belief that this stock market crash doesn't even prove the bears right, because it rests on the unpredictable appearance of what now appears to be the world's worst pandemic in a century. We approach a fascinating juncture. His call has always been that the Ice Age would end with American yields joining bund yields in negative territory, stock markets back to their 2009 lows, and the economic situation so desperate that governments have no choice but to change tack so dramatically that they create inflation. At that point, stocks would become a far better bet than bonds and the world would embark on a new direction. It struck me that the moment when the ice melts could be getting close. When I phoned Edwards to ask him this, I discovered that he was wrestling with just this question, and on Thursday he published a piece in which he did, indeed, predict that the end of the Ice Age could be imminent. (Full disclosure — possibly because of our chat, I am one of a number of people who get a name-check in his piece, which is worth reading, and can be found behind the SG paywall here). His reasoning is fascinating for bulls and bears alike. He remains convinced that the scale of the downturn now is due to the build-up of debt that preceded it. The coronavirus turns out to have been the trigger for a debt reckoning that would have happened at some point: leverage was built up on the premise that nothing bad happens. And something very bad has now happened. Hence many of us believe that central bank actions over the last decade have made the current already bad situation much worse than it otherwise would have been. This is how he summarizes what he had expected to bring the end of the Ice Age (in the era pre-coronavirus): I expected the anger of the populace and the populism it would engender would bring a transition in economic policy away from the increasingly discredited Quantitative Easing (QE), which I believe actually did very little good (in reviving the economy), but much bad (in that it exacerbated wealth and intergenerational inequality - helping to drive the rise in populism). Instead of more QE, I wrote that some variant of Helicopter Money such as the increasingly fashionable Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) would be adopted in some shape or form. It would in effect be the monetisation (of rapidly increasing public sector deficits) in all but name. It would not be announced with great fanfare. It would just be done. It looks to me as though he is in the process of being proved right about this. With Republicans in Congress anxious to send out checks to all Americans, and Angela Merkel ready to expand the German deficit, it seems as though the case for helicopter money has suddenly become almost the undisputed orthodoxy. And that lines up with the Edwards belief that the regime would be "such a major event that it can only be implemented during a crisis." The crisis is here, and the synchronized use of fiscal and monetary measures has, in Edwards' words, begun to cross, if it hasn't already, the Rubicon. "It was going to happen anyway, but it has come sooner than we expected. What now for The Ice Age?" Don't worry, Edwards is still not wildly positive. His reading of the coronavirus crisis is dire indeed. He cites the following charts, from the iconoclastic U.K.-based economist Steve Keen, which contrast U.S. indebtedness during the Spanish flu of a century ago with indebtedness today. The world was still on a war footing when that happened, and used to war-time discipline; this time will be different and more damaging economically, Edwards believes:  As for bond yields, the sheer deflationary impact of the recession he sees ahead should still bring Treasuries down to the negative level of bund yields. The last week has seen a stunning reversal in the bond market, with real yields positive again after moving well into negative territory:  Edwards points out that something very similar happened at the outset of the post-Lehman phase of the last crisis, with everything sold off, including even bonds, in the initial liquidation phase. Subsequently, yields went far lower:  So the moment when the ice melts is still a way away in terms of the money to be lost. His base case, which he shares with financial historian Russell Napier, is that U.S. stocks will need to revisit their lows of 2009, or fall even lower. But in terms of time it isn't far away. From now on, when central banks intervene in the bond market, he says, it "is not about yield suppression or yield curve control. It is about financing fiscal expenditure and tax cuts." Once bond yields go back down again, that will be a signal that the moment is approaching. The same is true of a reversal for gold, which has fallen so far in this crisis. It did so at the outset of the last two big market breaks, so a reversal could be useful signal:  For a man who has enjoyed his reputation as a cussed and contrarian perma-bear for the last decade, and has sometimes come close to self-parody in that role, it is interesting that Edwards isn't displaying his characteristic certainty about the coming turn. He admits that after being wrongly out of the market for so long, he badly wants to get the call on when to buy right. Timing is hard, particularly when the coronavirus has introduced the possibility of economic damage on a scale that even he didn't predict. On the prospect of helicopter money, he says: "Of course it will ultimately work to trigger a recovery, but we collectively have no idea how deep this economic and financial market meltdown will be — especially if you adhere to my own view about the inherent extreme vulnerability of the system even before the coronavirus hit." With so much uncertainty, he is prepared for the possibility of calling a turn even if Treasury yields never sink into negative territory, or if stocks don't drop below their 2009 lows. Many will still say that he has been so wrong for so long that he is best ignored. But ad hominem arguments like that are never the best. The framework he presents is a good one. There will be a buying opportunity soon, which will likely come amid an epic crisis for the West. He might well help us to find that opportunity. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment