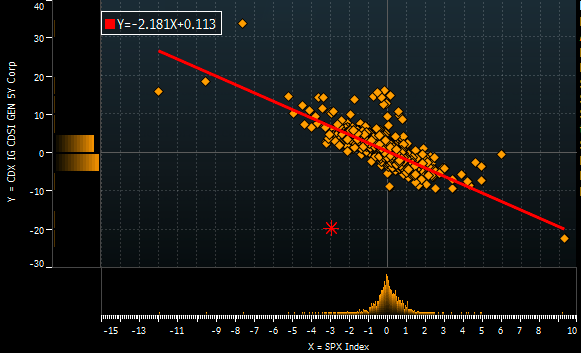

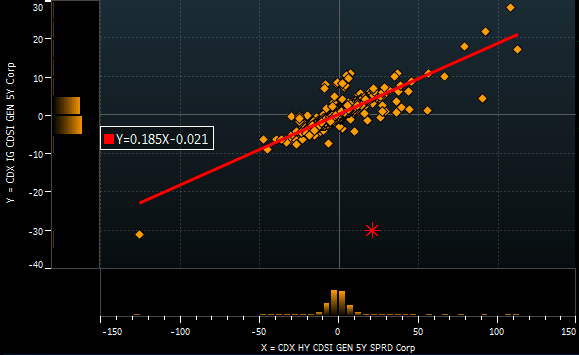

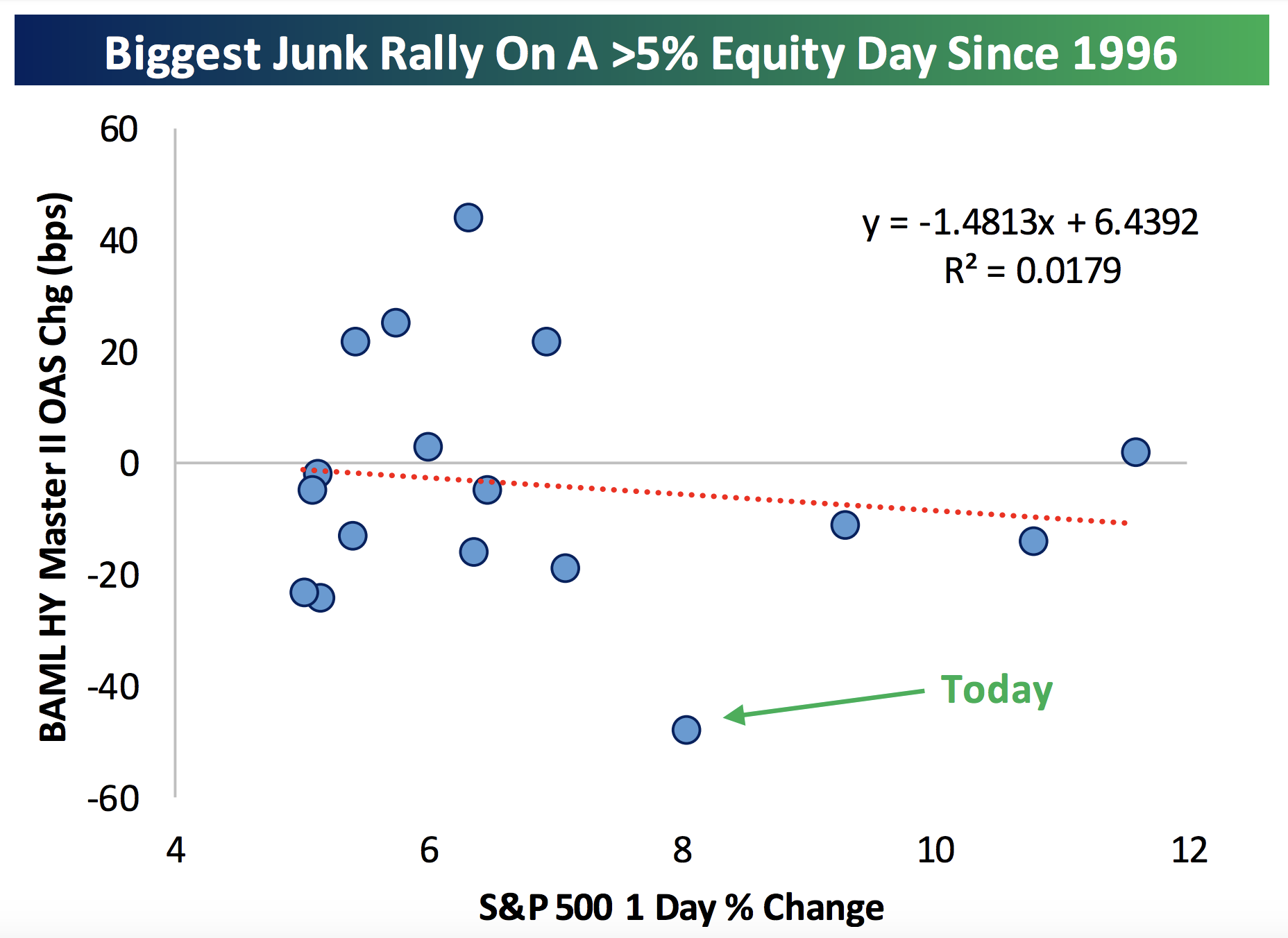

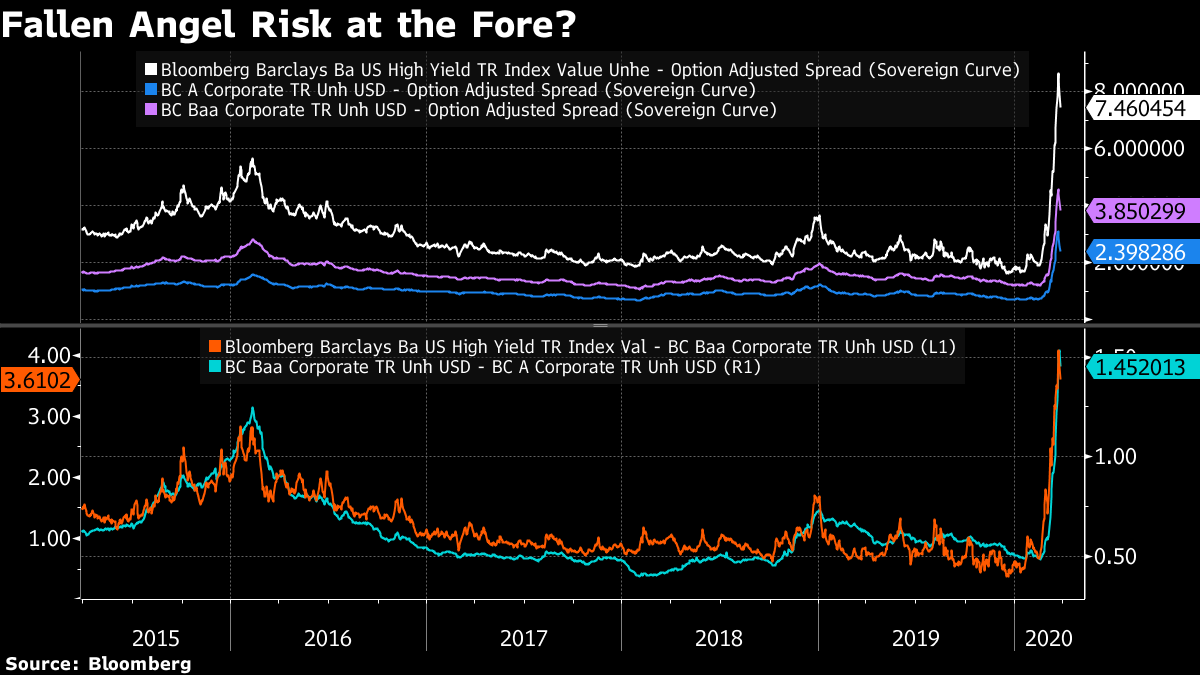

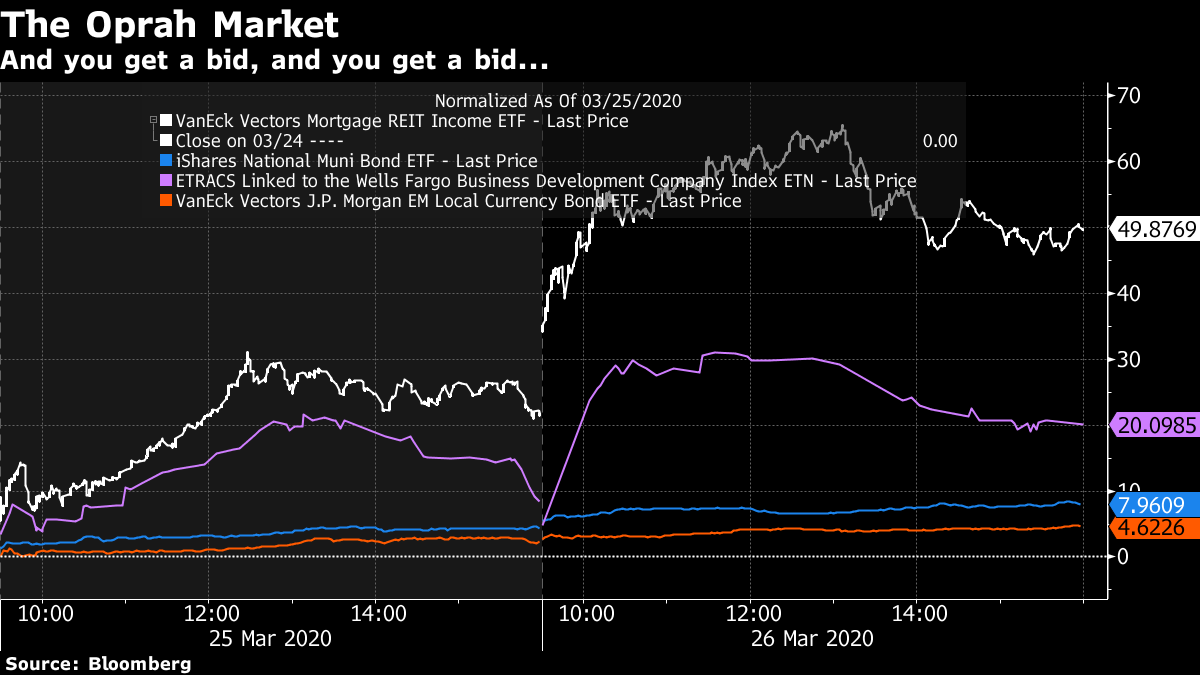

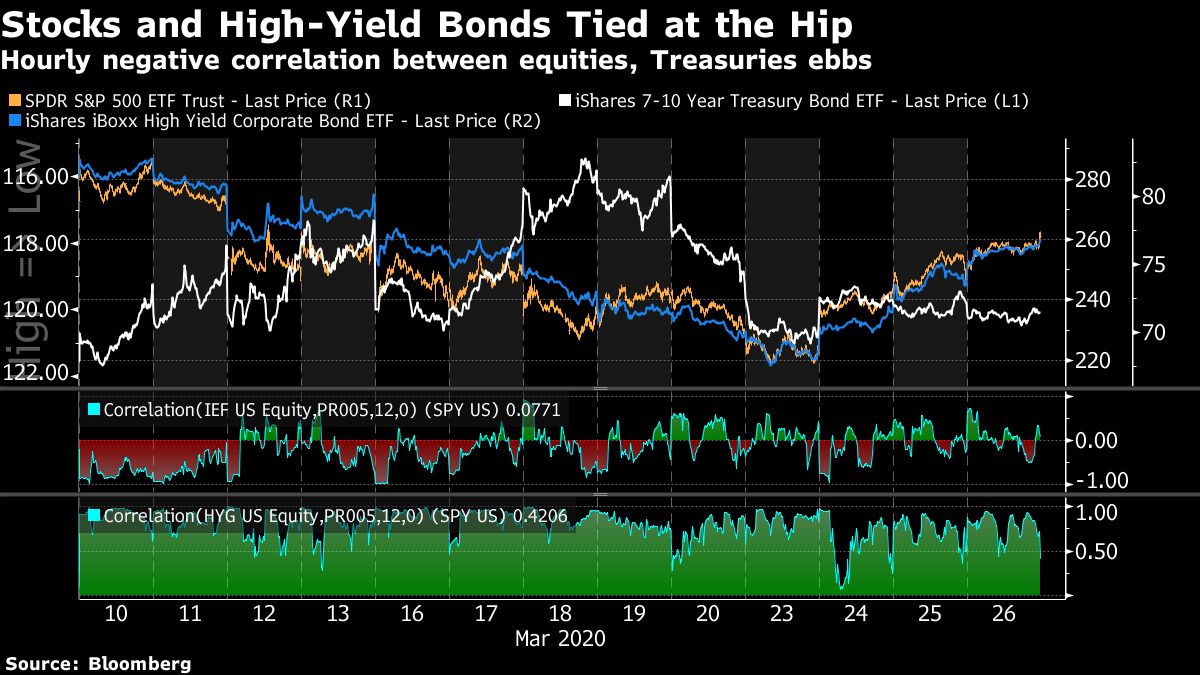

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that thinks whenever the Fed runs out of ammo in its pistol it picks up a bazooka. --Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter Days Like These So, uh, that happened. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (technically) entered a bull market, with a more than 20% gain in a three-day stretch that culminated in a massive advance on a day when U.S. initial jobless claims posted a surge that was quadruple the previous record. Last week, we discussed how liquidity conditions were so poor and raising cash was so front-of-mind that there was a pan-asset sell-off. Rather than risk-on versus risk-off, the recent price action could be more charitably described as a return to "liquidity-on" conditions from "liquidity-off." Everything rose: it was the first time since at least 2002 that the S&P 500 Index rose 6% or more and the long bond (as proxied by the TLT ETF) rose at least 0.4%.  There's a lot of talk about the mother-of-all-rebalancings coming, thanks to the extreme market moves to date this month. Deutsche Bank estimates pensions may dump about $40 billion in Treasuries. JPMorgan Chase is touting rebalancing as a $850-billion spark for global equities. But on Thursday, it seemed a whole lot simpler: more like a rebalancing from the cash everyone had been pining for back into the financial assets they had eschewed. Lessons Learned A trip down memory lane is required to attempt to comprehend the scale of this week's market moves. The superlatives associated with the immense swings take us back to the 1930s. Think of what was going on in America back then, and what the policy response was! We all learned it. Even foreigners (well, Canadians at least) get taught about some of it in grade school. On Tuesday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average posted its biggest one-day gain since March 15, 1933. That was the first session markets reopened following an extended bank holiday instituted by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt – because so many of them were failing in the midst of a bank run. In the interim, the Emergency Banking Act was passed. That gave the federal government the powers of receivership over all national banks threatened with suspension, helping bolster confidence that Americans could trust the banks with their savings. Thursday marks the culmination of the biggest three-day rally in the S&P 500 since the period ending April 20, 1933, when FDR took the radical step of de-pegging the U.S. dollar from the gold standard. (Technically we are backdating the index here, as it only began in the 1950s.) These were policy actions that succeeded in chopping off the left tail of systemic financial instability – much like the modern-day Federal Reserve's rapidly expanding suite of programs to address liquidity and credit risk. In the 1930s, these measures were accompanied by expansive fiscal policy, as is expected today. Think about the size and scope of FDR's New Deal programs. Even they were insufficient to bring an unemployment rate of 25% in 1933 into signal digits before World War II was well underway. The lesson from history: policies sufficient to shore up the financial system and spark furious rallies in risk assets are not enough to completely ameliorate supremely negative outcomes in the real economy. That bears remembering when assessing the fiscal package that's on the verge of clearing Congress. There's no sign the bond market finds it a game-changer in terms of the outlook for growth and inflation. "In the U.S., we see the 10-year reach a low of 30 basis points and end the year at 65 basis points as the Fed buys a significant amount of net issuance to support the economy," writes Priya Misra at TD Securities. "Since we don't forecast the Fed hiking until after 2021, we expect the 10-year to stay below 1% through 2021."  Stimulus Funding Nathan Tankus, research director at the Modern Money Network, deems nearly a quarter of the funds in the fiscal support bill to be a "useless accounting gimmick." At question here is the funds devoted to special purpose vehicles that will be backed by the Fed to facilitate assistance for beleaguered asset classes. There's no reason to park so much cash there unless officials are worried about the potential of exposing the central bank to losses that leave it in the position of having a negative net worth, which is effectively just an accounting exercise with little true meaning. ``Each SPV associated with a specific Federal Reserve facility could be capitalized by a single dollar,'' Tankus argues. "It really does seem to be the case that Congress people are taking large political hits for an irrelevant accounting gimmick." Allowing the Fed to hyper-leverage a smaller amount of funds would allow the "fiscal space" embedded in this bill to go elsewhere. On that note, governors are lamenting that the plans don't sufficiently address their financial needs. There is no indication, from the bond market or ratings companies, that this Congressional bill maxes out America's fiscal capacity, far from it. Even Fitch reaffirmed the sovereign AAA credit rating on Thursday afternoon. Interest rates are near historic lows. Yet the interest rate on the money we're not spending by the delay in getting a fiscal package out the door is sky-high. As Andrew Maragni quipped on Twitter, it's like forgoing repairs on your roof and ultimately spending 10 times more to fix it after it caves in. Massive red ink on the federal ledger – with uncertain implications for Treasury yields – are a forgone conclusion. As Bloomberg's Joe Weisenthal puts it: "Government deficits are going to soar. It's a fact. Question is whether we do it the hard way or the easy way. Easy way: Spend a ton of money up front to save the economy. Hard Way: Let the economy collapse, and watch the tax base shrivel. Either way: Deficit soars." The Fed Has Done More Some feared the Federal Reserve was "out of ammo" after lowering interest rates to the zero lower bound more than a decade ago. It wasn't, and it really never will be. (Bloomberg Opinion columnist Tim Duy makes the case that the central bank can do even more, but let's take stock of what's already been set in motion.) The central bank first set into motion facilities that would improve funding conditions and liquidity. The Fed has since embarked upon open-ended quantitative easing and credit support, and the effects are rippling beyond the asset classes it's directly (or quasi-directly) helping. BlackRock, as it happens, is assisting the central bank in carrying out credit purchases. LQD, an investment grade bond ETF, soared 7.4% on Monday on the heels of the central bank's announcement. The relative outperformance of investment grade five-year CDX (tightened dramatically) versus the S&P 500 Index (crushed) was the biggest in the history of the index.  Bloomberg Bloomberg Fund flows into investment-grade bonds have been steeply negative despite the Fed's actions and price recovery, which suggests inflows into IG bond ETFs are a function of issuers catching up to the premium to net asset value that's developed as these more liquid expressions of the high-grade market get Fed backing. But at the start, this was just a case of investing alongside the Fed winning, and everything else losing. Monday also saw the most anomalous underperformance of high-yield CDX versus IG on record.  Bloomberg Bloomberg "However, high yield should eventually benefit indirectly as credit risk is removed from the market and potential fallen angels receive necessary capital," wrote Daniel Sorid at Citigroup. Right he was, at least for now. Bespoke Investment Group flagged that the subsequent tightening in high-yield spreads on Tuesday was the best such showing for a 5% in advance in the S&P 500 since at least 1996.  Bespoke Bespoke Nonetheless, the potential for investment-grade creditors to lose that rating is in focus – especially after Ford became a fallen angel. Citing the European Central Bank's experience, Hans Mikkelsen at BofA Securities argues that the presence of the Fed as a high-grade quasi-buyer will firm the resolve of borrowers to retain that credit rating (even if an economic downturn makes that tough). "A sizable rating upgrade cycle in European high-yield followed the launch of the ECB Corporate Sector Purchase Program" in 2016, he writes. "Now obviously we are not predicting a US HY upgrade cycle as there is a recession, but would think that at the margin lower-rated U.S. IG companies should now be willing to fight more for their IG ratings." If investors were overly concerned about fallen angel risk, it seems odd that the relative surges in A-BBB spreads and BBB-BB spreads during the stretch of risk aversion would map so cleanly onto their 2016 peaks. Perhaps the perception of downgrades was sky-high then, too. Or perhaps it reflects Fed support for many credits that may lose high-grade status.  It wasn't just high yield that found buyers: all the orphans of credit/income – municipals, shadow-banking lending vehicles, emerging-market debt and even mortgage REITs (a space which has been an absolute zoo) caught a bid over the middle of the week.  A solidifying high-yield market similarly bolstered stocks. As in accordance with a "liquidity-on" regime, a hyper-correlation between stocks and junk bonds has remained intact.  There's no way to ascertain whether the Fed-induced improvements will have staying power. But that's what's been happening so far this week. |

Post a Comment