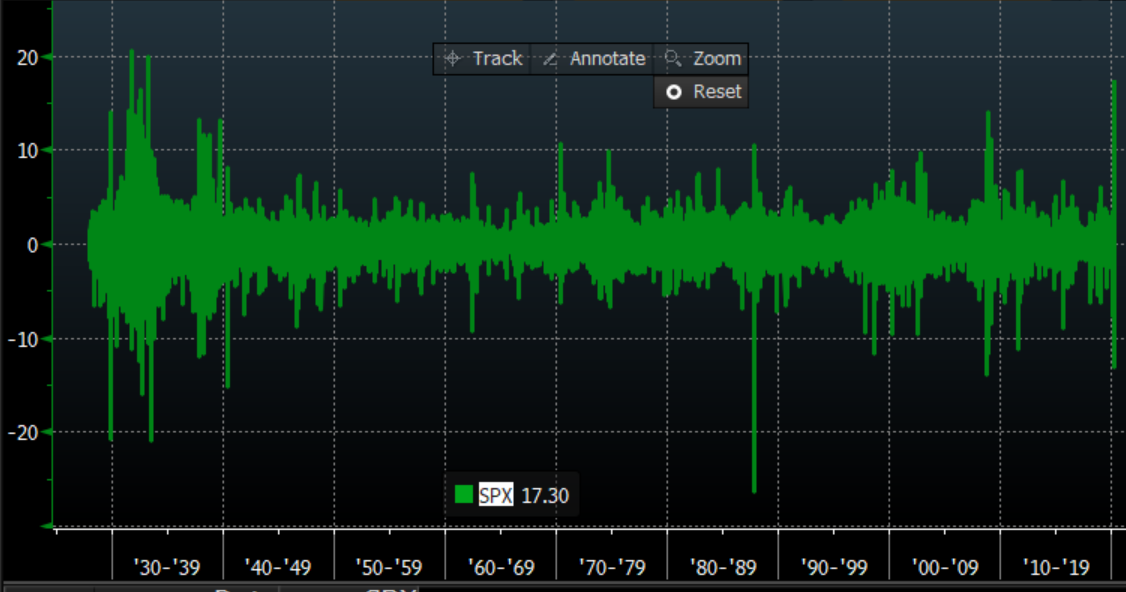

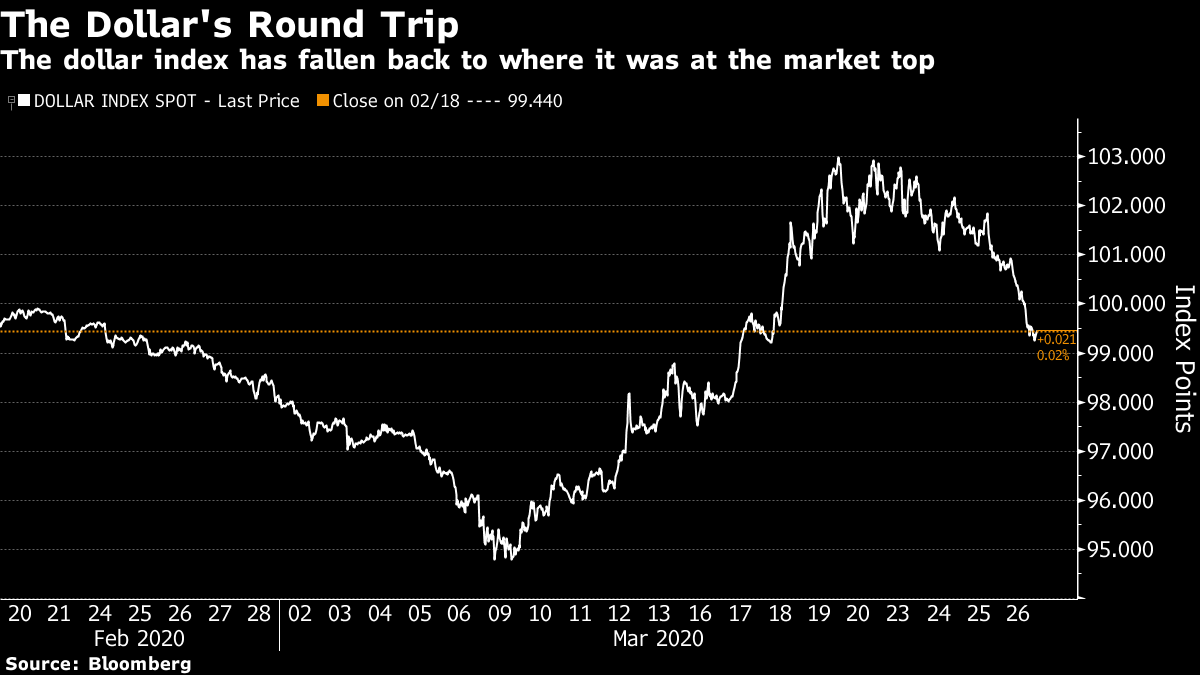

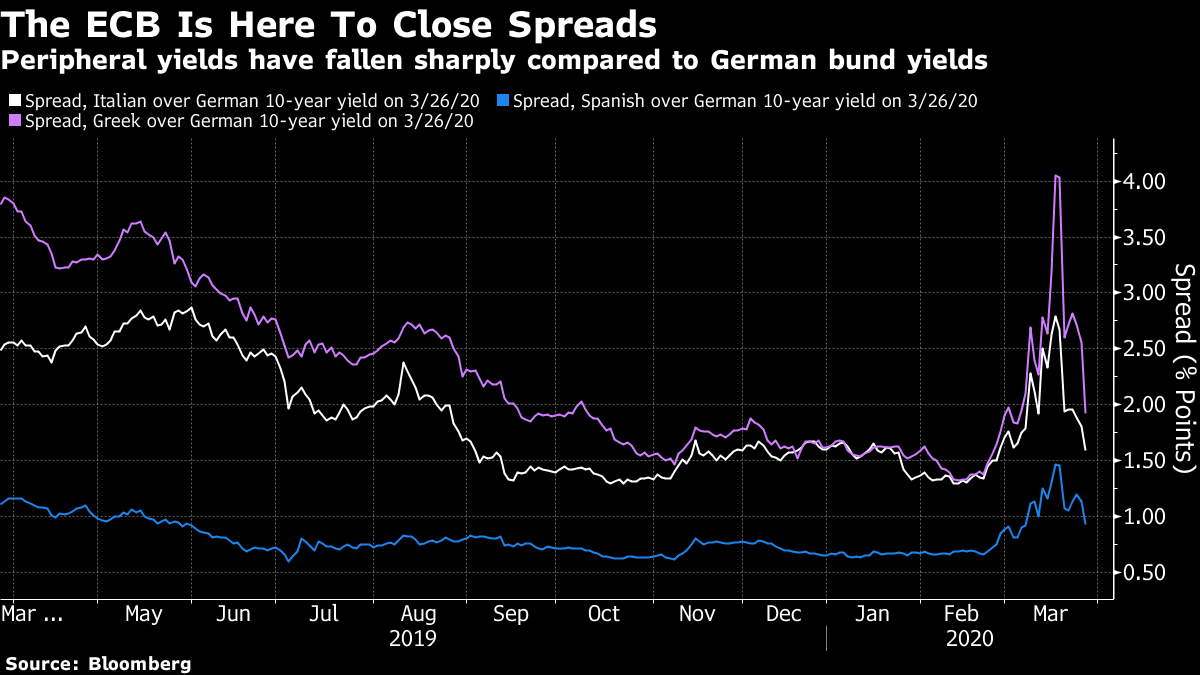

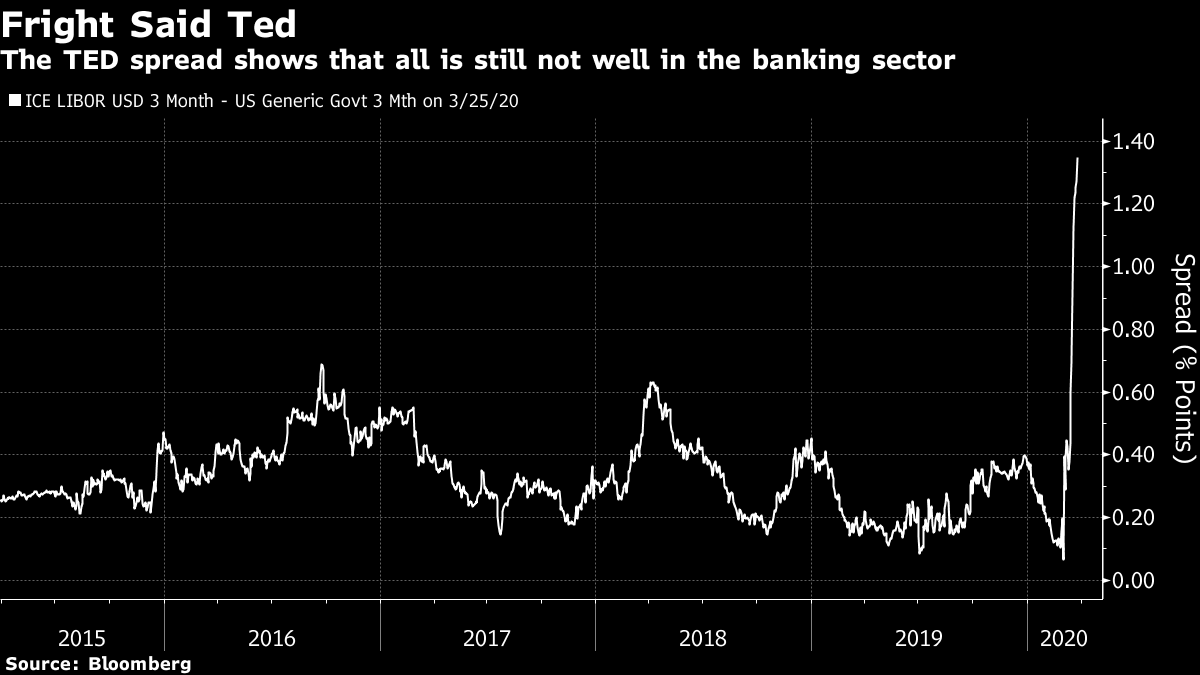

| Markets don't do subtle. Thursday brought news of the worst week for new jobless claims in history, and also a renewed rally for the U.S. stock market. The S&P 500 has logged its best three-day return since 1933. Only two such three-day periods have seen better returns, and both were during the Great Depression. Here is a snapshot of a chart (produced on ECWB, for Economics Work Bench, on the terminal):  After a fall that was unprecedented in its speed, a rebound that was almost as fast isn't necessarily that surprising. But it's still impressive that those who bought an S&P 500 exchange-traded fund Tuesday morning had already made profits of 18% by Thursday. The index did this despite the announcement before trading started Thursday that a record 3.3 million Americans had signed on for unemployment insurance the previous week — a number quite without precedent, and worse than most economic forecasters had predicted. As I said, markets don't do subtle. After the announcement of such horrible news for so many Americans, why not make lots of money on the stock market? I hereby confidently predict that the stock market won't carry on gaining at this rate for the rest of the year. Beyond that, what should we make of it? There is an inevitable tendency to try to link any given market move to that day's news, which should be resisted. The fiscal stimulus has obviously been coming down the pike for the last few days, and the virus figures couldn't clearly be read as either better or worse than a reasonable expectation. Even so, I do think it is fair to attribute this rebound to some extent to an absence of bad news. The greatest financial alarm of recent weeks was the dollar shortage, which led to a sharp strengthening in the U.S. currency. That appears to have abated. After a remarkable round-trip, the dollar index, mapping the dollar against its main trading partners, is back to where it was at the top of the stock market on Feb. 19:  From the other side of the Atlantic, there is reassurance from the sharp reduction in the yields of peripheral nations' government bonds, after the European Central Bank stepped up its support for the bond market. A recurrence of the sovereign debt crisis that roiled the euro zone a decade ago at one point seemed a real possibility; it looks as though the ECB has done enough to stop that from happening. Although people won't forget that it was largely thanks to some dreadful communication by the ECB that sovereign debt ran into trouble in the first place:  This doesn't mean that all the worries about credit or the banking system have gone away. Far from it. Most disconcertingly, the improved animal spirits of the last few days have done nothing to unblock the plumbing of the banking system. Veterans of the financial crisis of 2008 will probably remember obsessively checking the TED spread, which shows the spread of the Libor rate at which banks lend to each other over the equivalent T-bill rate. Arguably it is the ultimate measure of stress and distrust in the banking system and, driven by the intense demand for dollars, it is looking just like it did in 2008:

Somehow, there was enough enthusiasm around to ignore the TED, at least for a day. To the absence of bad news, add what looks to me like over-confidence that the state has done all the market wanted, and that asset prices will be great in the future. One of my favorite macro market participants sent me an email which, with tongue firmly in cheek, asserted that "the 'state has taken over capitalism' explosion is on." This might be tough on Ayn Rand, the University of Chicago and libertarians in general, he said, but "it is what it is." He concluded: "Just like in 2008-09, states have given the market all it wants. Even faster."

And with such enthusiasm at its back, the stock market rebounded. Even faster.

Another Solomonic Trade-Off

How do you measure the life of a woman or a man? The trade-offs society will have to make if it turns out that a lengthy lockdown is needed to deal with the coronavirus continue to be horrific to contemplate. Yesterday I offered a paper attempting to work out a mathematical structure for that trade-off, and suggesting that a recession as bad as the last one could cause as much loss of life as a lockdown had saved.

This piece in The Guardian by the prominent British economist Jonathan Portes is a rebuttal. You can also read this piece in Nature that suggests that recessions are actually good for longevity. If that sounds counterintuitive, there are fewer cars on the streets, less money for booze and tobacco, and more time for exercise. Against that it is always worth re-reading the seminal study by Anne Case and Angus Deaton on "deaths of despair" — in the U.S., life expectancy among mid-life non-Hispanic white Americans is actually falling, largely because of overdoses, deliberate suicides, and illnesses linked to obesity and depression. This is an economic phenomenon which has been exacerbated by the slow recovery, with deepening inequality, of the last decade. Technically, there was no recession for most of the time that they chronicle deaths of despair increasing. Case and Deaton's book on this subject has just been published, and without the pandemic it would have been a major event.

I will continue to say that an attempt to rush back to normal would be a dreadful error. But the risk of added deaths of despair, which the president has mentioned at times in his coronavirus briefings, is a real one. The pandemic seems virtually certain to exacerbate the flaws in capitalism that Case and Deaton identified. So whatever happens, we have a very different economy to look forward to in the future. Enjoy the weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment