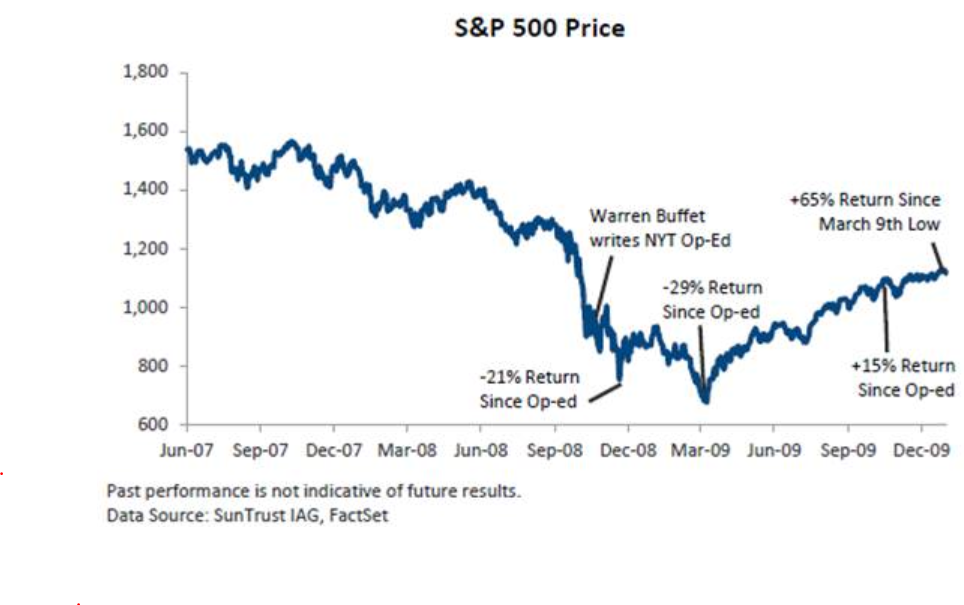

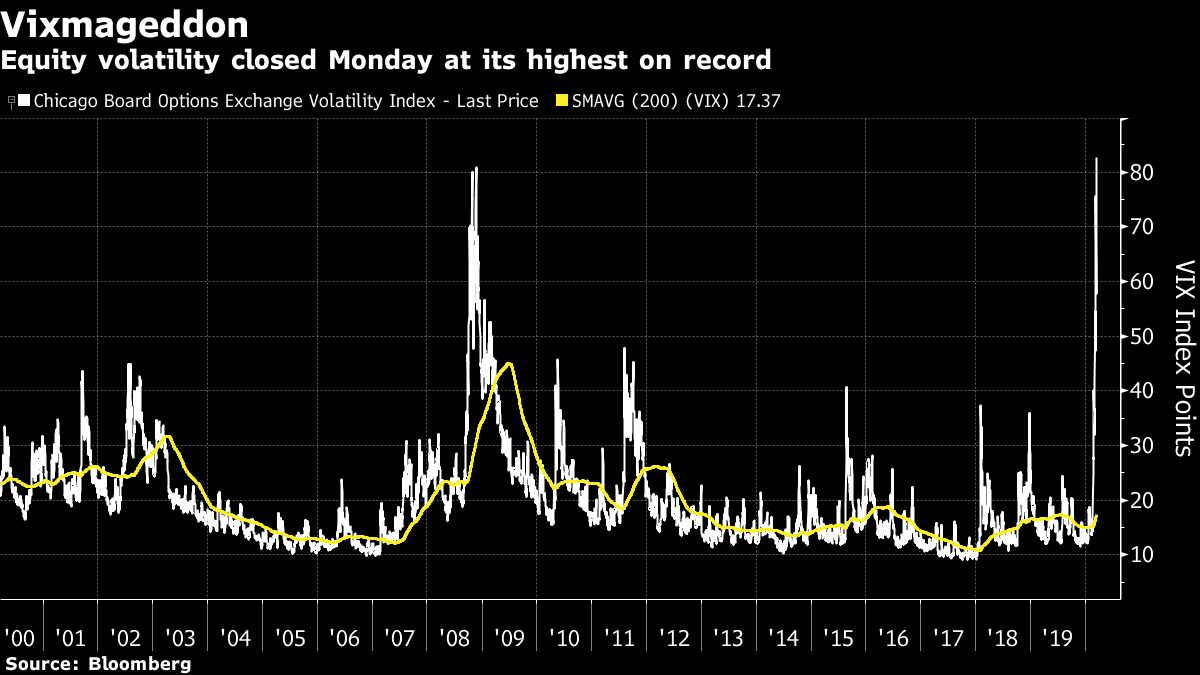

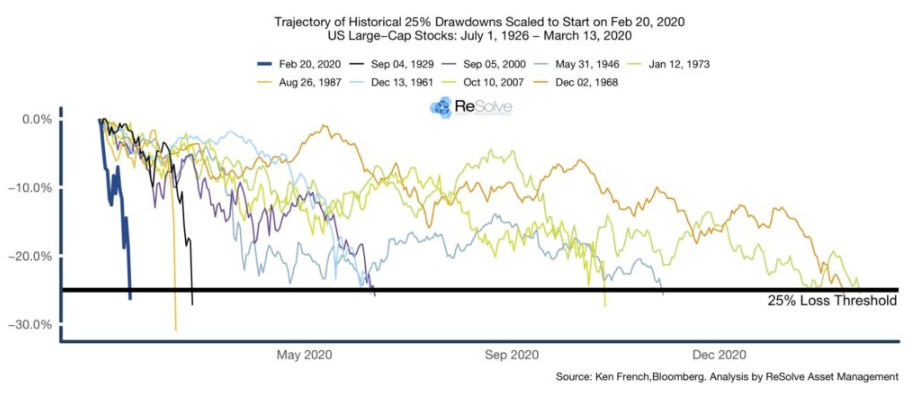

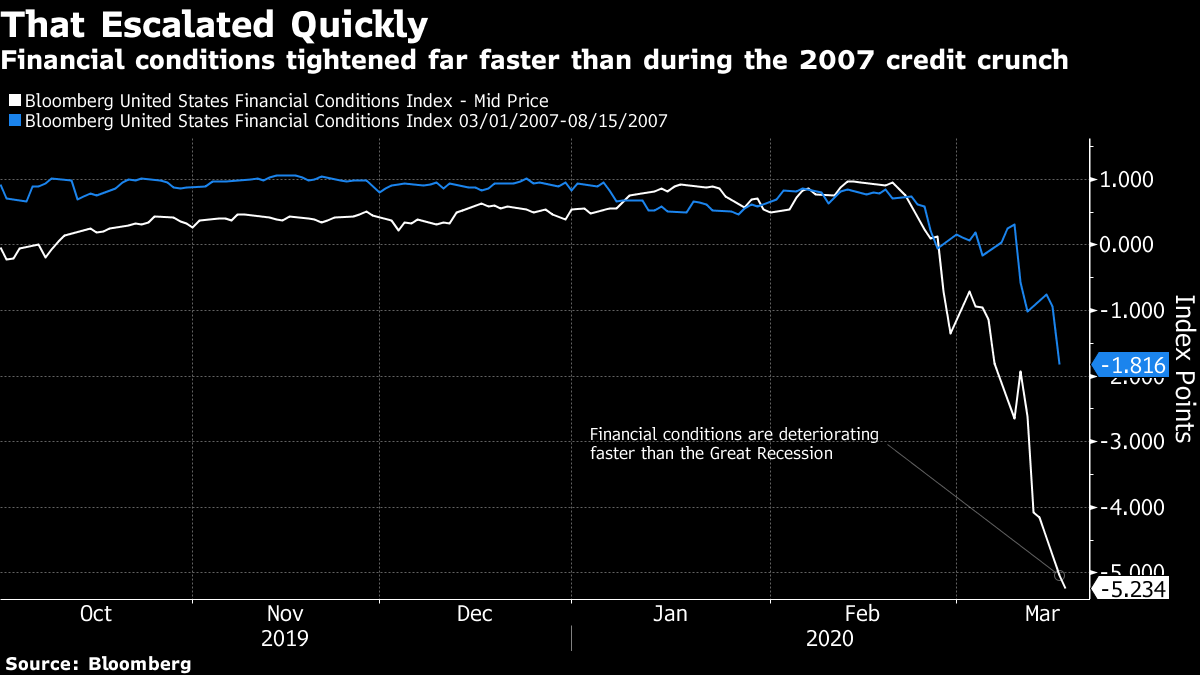

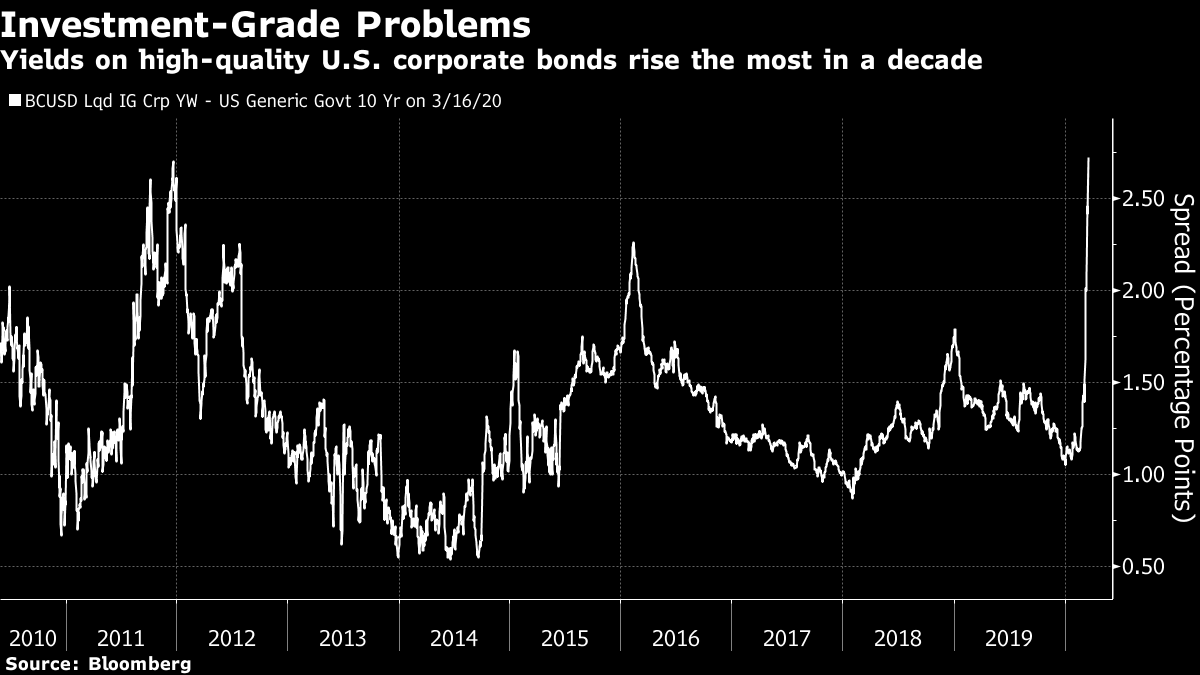

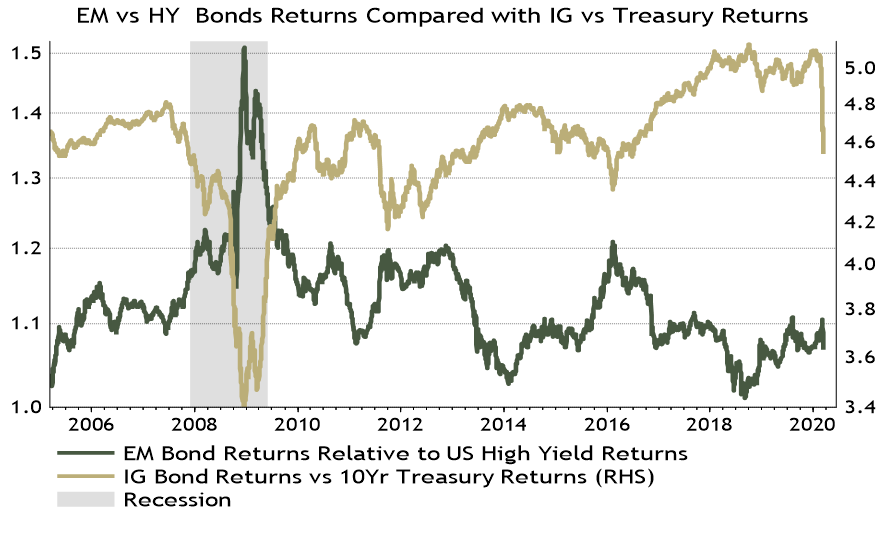

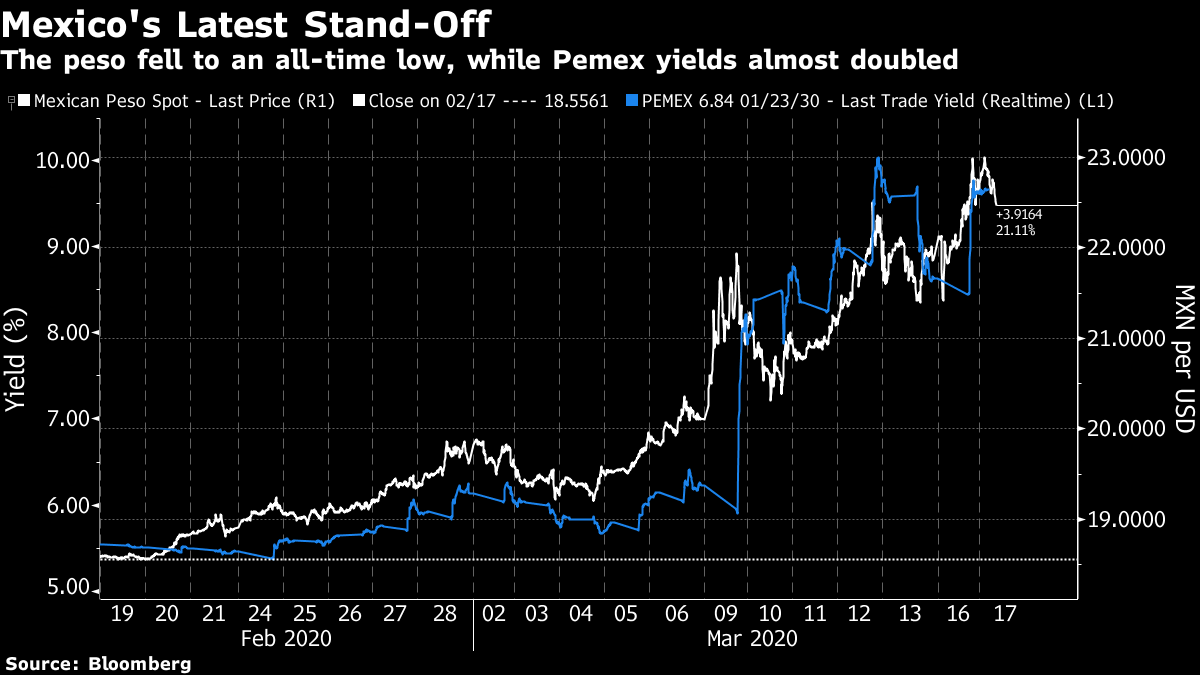

Do Something? In times of crisis, the imperative is to do something — anything. Watching and doing nothing at times like this merely accentuates a sense of powerlessness. The U.S. stock market has just suffered its single worst day since the Black Monday crash of October 1987, while the world shuts down in the face of the gravest pandemic in more than a century. Surely there is something we can do? Back in October 2008, Warren Buffett penned a famed op-ed. for the New York Times, announcing that he was buying stocks and urging others to do the same. As the following chart from SunTrust shows, his timing wasn't perfect, and at one point he was sitting on losses — but by the end of 2009 he already looked prescient. If opportunistic buying is good for Buffett, why shouldn't the rest of us try it?  Extreme situations create opportunities; they also offer the chance to lose ungodly sums of money. That is why we need to be careful with what psychologists call activity bias. It is a natural emotion, as I have written before, and doing nothing requires great self-discipline. But it is often what the situation calls for. To mention two examples from sports, soccer goalies generally dive in one direction or another when attempting to save a penalty, because to stay standing in the middle makes them look dumb. This means strikers have come to realize that sometimes their best chance is to blast the ball straight down the middle. In baseball, the statistical revolution of the last two decades revealed that one of the most valuable skills, and one of the most difficult to develop, is to have the courage to let a pitch pass by without swinging at it. So what is the case for masterly inaction in the current extraordinary market conditions? By the end of Monday's trading on Wall Street, the CBOE VIX index, which measures equity market volatility, had topped 80 for the first time since the Lehman Brothers crisis in 2008:  The last time volatility spiked this high, it came after more than a year of a steadily escalating credit crisis. This time, volatility has erupted within a month of an all-time high for the U.S. stock market. In such conditions, placing money in the market, or trying to estimate the best timing, is surely no more than gambling. I hate to repeat an ancient and irritating cliche, but there is nothing that markets dislike as much as uncertainty. And at this point, it is hard to see how uncertainty could be greater. The world's major economies have voluntarily shut down large tracts of activity. They have effectively chosen to impose a recession upon themselves, correctly judging that this is preferable to allowing the pandemic to do its worst. So markets now work on the total certainty of a recession. Yet if we look at the "Nowcast" produced by the Atlanta Federal Reserve, intended as a high-frequency and up-to-the-minute measure, the U.S. economy is booming:  At a point where all data are uselessly backward-looking (even a "Nowcast"), the basis cannot be there for informed investment. Then there is the argument made this week by Mebane Faber, an asset allocation expert. If you worked out a sensible asset allocation coming into the crisis, it should have suffered far less than the stock market — particularly if it had a decent chunk in bonds. If this was a portfolio that was built with the notion that a crisis like this would happen at some point, you should have the courage of your own convictions. Stand still as you look the striker in the eye, keep the bat on your shoulder, and leave your portfolio where it is. Or to quote the late Jack Bogle (as cited by Faber): "My rule — and it's good only about 99% of the time, so I have to be careful here — when these crises come along, the best rule you can possible follow is not "Don't stand there, do something," but "Don't do something, stand there!" This Is a Financial Crisis. Sorry. One more point needs to be made. Evidently the world currently faces a public health crisis, and everybody should give priority to fighting that over everything else. It is the virus that has triggered problems in the financial world. But that doesn't mean that this isn't a financial crisis. It is. And if it isn't fought with the usual financial weapons, it risks doing deep damage. The only real difference is that this crisis has happened very rapidly. This chart, from Faber, shows that this is the quickest 25% drawdown for U.S. stocks on record. (And that was before Monday's renewed sell-off.)  With such a rapid deterioration, it is unsurprising that financial conditions have also tightened at a record rate. As the following chart produced by my Bloomberg colleague Michael Cassidy demonstrates, financial conditions have tightened further and faster than they did in the summer of 2007, when a rash of bankruptcies for subprime borrowers caused several sections of the credit market to freeze:  What started the crisis is no longer relevant to people in finance. They should leave fighting the virus to the public health authorities — and get on with averting deeper financial damage. Where Is the Crisis? U.S. Credit The market is good at revealing where the problems are, and so is the Federal Reserve. Its support for credit markets makes clear that there are concerns there — even investment-grade credit has deteriorated remarkably quickly. Compared to Treasuries, Bloomberg's index of liquid investment-grade corporate debt is at its highest yields in a decade, after a breathtaking deterioration:  Emerging Markets Then, look at emerging markets. The Fed also announced swap lines with other major central banks, in an attempt to ease what appears to be a shortage of dollars. This is traditionally a problem for emerging markets — and the following chart, from Ian Harnett of London's Absolute Strategy Research Ltd., makes that point. Usually, in a crisis, emerging market sovereign bonds are perceived as much safer than U.S. high-yield bonds. Unlike small U.S. companies, emerging-market governments are free to raise taxes. But they have fared no better than junk bonds so far:  Meanwhile, emerging-market currencies continue to plumb all-time lows. The most spectacular performer is the Mexican peso, which dropped below the previously unheard of level of 23 per dollar. Yields on bonds issued by the national oil company, Pemex, have almost doubled in the last week:  Europe: Back in Trouble Meanwhile, the deepest trouble may be in Europe. Obviously the continent is currently in the forefront of fighting the virus, which has become a full-blown tragedy in Italy. But it also suffers from a banking system that never regained confidence after the 2008 crisis, and an apparatus for fiscal and monetary policy that leaves it open to speculative attack. The price-book multiple of euro-zone banks is at an all-time low. And the spread between Italian and German bond yields is widening again, in a familiar sign that the structure of the euro zone, still largely unreformed after its existential crisis of almost a decade ago, still inspires little confidence:  As for Europe's stock market, I commented a month ago that it appeared to be at a moment of revulsion. That was just before the virus hit with full force. So I stand corrected — but this certainly begins to look like revulsion now. It is the kind of extreme action that policymakers will have to deal with. The fight with a deadly virus only adds to the urgency:  This is a far-spreading financial crisis, which has now enveloped much of the world. The likelihood is that these problems can be resolved, because that is what normally happens. Betting on disaster (for example, by betting on European spreads to widen) can be costly and dangerous. But this is only the second time that crises have hit so many different parts of the world financial system at once. Even if these financial problems can be resolved, public health authorities still need to tame the virus. Masterly inaction won't do for the world's policymakers. They need to make some huge decisions that could shape the world for generations to come. For investors who entered the crisis with reasonably balanced assets, though, inaction looks like a masterly strategy indeed. Correction I made a bad error in yesterday's newsletter. There have been three unscheduled closures of the U.S. stock market in modern times, not two. In addition to 9/11 and the chaotic day when Wall Street woke up to the Asian crisis, I forgot that the market was also forced to close by another natural disaster — Superstorm Sandy in October 2012. Thankfully, the error doesn't greatly change the analysis, as the closure for Sandy had no obvious ill-effects. Despite a damaging storm that directly harmed many of the people most active in trading the market, volatility stayed low. The closure is marked:  I don't think the arguments for and against a market closure are affected. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment