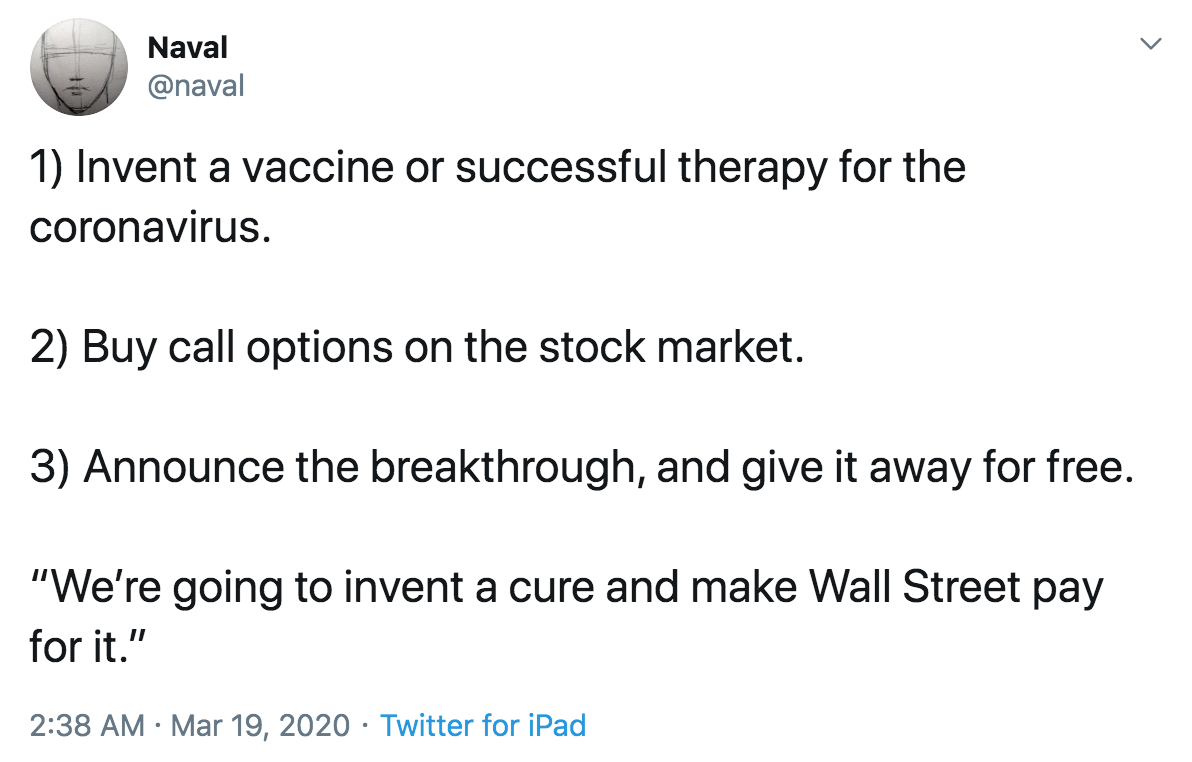

Financial engineering Here's a tweet from Naval Ravikant of AngelList:  It is worth saying that the first part is the hard part; if you could do it in five minutes in your kitchen, then this would be a great strategy, but really it would require money and time for science and clinical trials and regulatory approval and manufacturing and so forth. The second part is also perhaps not trivial, as you'll want to be able to put a lot of money to work buying call options. Actually pursuing this strategy would require a large team of people—scientists and managers and lawyers and doctors and financiers—and an organization that you'd have to fund with nothing but the promise of future stock-market returns, and you'd have to time the options right, and the market would incorporate news about your work over time, and if you didn't actually find the cure you'd be out of pocket a lot of money, etc.; it is all in all more of a thought experiment than a viable plan. Still it's a thought experiment.[1] In some ways it is reminiscent of Joe Weisenthal's thought experiment about disruption and short selling: You could imagine starting a company that provides some existing service better and cheaper than the current incumbent public companies, and then instead of making money by charging for that service, you make money by buying put options on the public incumbents and profiting as their stocks go to zero. It is a strange and ghostly form of capitalism: You efficiently provide a service that people want, but instead of charging them a fair price for it, you make money through the abstract workings of the financial system. The lost revenue of your competitors can itself be transmuted into money—weird, but almost true—and you can profit from it. This is like that in reverse: You efficiently provide a service that people want, but instead of charging them a fair price for it, you make money through the abstract workings of the financial system. But in a nice way. Also a rather more straightforward way I guess: The increased revenue of all the other companies doesn't need to be strangely transmuted into money; it is money, and you just buy yourself a leveraged share of it. But you know what it is really reminiscent of? The theory here is that if you own a company, and you also own all the other companies in the stock market, your incentives are not to maximize the profits of the one particular company, but rather to maximize the joint profits of all the companies combined.[2] That is a theory that we talk about all the time! Usually I phrase it as "should index funds be illegal?" Because typically this theory is part of an argument that big diversified institutional investors (including index funds) who own shares of all of the companies in an industry will want those companies to maximize industry profits (by raising prices) rather than to compete for market share (by lowering prices). That particular strong form of the theory is controversial for various reasons, but some weaker form of it is surely true. If 100% of your wealth is tied up in one company, the success of that company is extremely important to you. You want it to increase its market share and its margins, to put competitors out of business and to charge its customers as much as the market will bear, because that's how you get money. A certain amount of antisocial behavior by the company could, in some circumstances, be good for you. But if your wealth is passively indexed to all of the companies in the economy, the thing that matters most to you is the health of the economy. You just don't care very much about who has how much market share; what you want most is to expand the overall pool of profits. Here too you might be inclined to certain kinds of antisocial behavior—behavior, like raising prices or lowering wages, that will be good for profits but bad for other values—but they will be different kinds. More … social … kinds. You see this explicitly in some of BlackRock Inc.'s environmental and social statements. BlackRock is a giant diversified fund manager that runs trillions of dollars of index funds and it really just cannot be bothered with thinking about which companies are better at defending their competitive positions. What BlackRock cares about, at the highest levels, is the general long-term health of corporate capitalism, and where it focuses its energy is on ways to help that system with its coordinating power. Every company, looking out only for its own profits, might have incentives to pollute and degrade the environment, but the companies collectively will be better off if the earth remains inhabitable. Unchecked competition might lead to a race to the bottom, but BlackRock can be a check on competition, and so it demands that companies do things in the greater good rather than for their own immediate bottom line. Sort of. On environmental issues at least. I don't know what you do with this. I will say that if I ran one of the big index-fund companies, and a pharmaceutical company in my portfolio developed a patented fully effective cure for Covid-19 that it could manufacture cheaply and planned to sell to anyone who could pay $50,000 a dose, I would call that company right up and say "no, you give that pill away for free, because the value to me of Covid-19 going away quickly and the economy recovering—the value to me as an owner of airlines and hotels and chain restaurants and retailers and every other company—is vastly, vastly greater than the value to me of your profits on that pill." Strictly as a financial matter I mean, strictly as a matter of my fiduciary duty to my investors. I would call my index-fund-manager friends and tell them to do the same thing, and between us we might own enough shares of the company's stock to make it do what we want. Later the antitrust authorities would ask us some uncomfortable questions about our conversations, but in these extreme circumstances that is a risk I'd live with.[3] You could just about imagine going further. If you ran a big index-fund company, and big companies that you owned announced that they were going to lay off lots of workers, would you call them up and say "no, keep paying your workers, you will lose money but it will minimize the disruption to the economy in a way that is good for the long-term health of all companies, and I own all the companies"? Maybe; that's a harder calculation. But surely some part of any recession is a coordination problem—everyone reduces capacity to respond to reduced demand, which further reduces demand, etc.—and the traditional cure for recessions is a collective societal response in which the government steps in to prop up demand without worrying too much about the near-term cost. The government has some huge advantages in performing that function (taxing power, the ability to print money and issue risk-free bonds, police power, democratic legitimacy), and I would not exactly recommend that BlackRock perform it instead. Still here we are in the thought experiment. If governments didn't fulfill their function of saving the economy, maybe index funds would? Elsewhere Well you know a long-running theme of this column is that collective ownership of all the companies through index funds is its own quirky form of socialism, but there's always regular socialism too: The White House's top economic adviser, Larry Kudlow, said the administration may consider asking for an equity stake in corporations that want coronavirus aid from taxpayers. "One of the ideas is, if we provide assistance, we might take an equity position," Kudlow said Wednesday at the White House, adding that the 2008 bailout of General Motors had been a good deal for the federal government. ... "This is a very big slippery slope because the ownership of private capital by government is not traditionally consistent with capitalism," said Kevin Caron, portfolio manager for Washington Crossing. "This is a politically charged topic." It is a cliché at this point to say that a lot of capitalists become socialists in financial crises, but there's a reason for it! The crises demand collective responses. Meanwhile here is a proposal from Steven Hamilton of George Washington University and Stan Veuger of the American Enterprise Institute, those bastions of socialism: If every small- and medium-sized business in America was supported by the federal government to retain their workforce through the crisis, much of its economic impact would disappear. The government should provide immediate funding for

emergency loans to any small- and medium-sized business in America. Basically the idea is that banks would lend businesses their revenue during the crisis, the Fed would guarantee the loans, and then, if the businesses didn't lay off employees, the government would forgive the loans through tax credits. A similar proposal was "circulating on Wednesday among White House officials," and it seems like a good approach! What if you're short though? I mean, look, instead of (1) buying S&P call options and (2) inventing a coronavirus vaccine, you could have (1) bought S&P put options and (2) invented the coronavirus. I do not recommend it, for any number of reasons. (I believe it is covered by the Fifth Law of Insider Trading.) On the other hand: Billionaire hedge fund manager Bill Ackman made headlines with his "Hell is coming!" coronavirus rant that one CNBC anchor admitted was "a bit of a conflict" with Ackman's position as an investor looking to buy stocks low. During a midday interview on CNBC Wednesday, Ackman warned that "Hell is coming" if the United States doesn't immediately and completely shut down. That portion of the interview got a lot of attention, but Ackman's full interview was 28 minutes of abject and unrelenting doom that was peppered with bouts of near-sobbing, and which many CNBC personalities and others credited with contributing to the slide in stock prices. And later in the day, CNBC anchor Wilfred Frost admitted that there was "a bit of conflict" in allowing an investor to potentially influence a market environment that he stood to benefit from. I don't buy it. For one thing Ackman doesn't seem to be short—he mentioned both that he is buying shares of Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. and that "it's going to zero along with every other hotel company"—and the alleged conflict is that he wants to drive stocks down so that he can buy them. But also a completely normal and unremarkable function of financial television is for people who own stocks to go on TV and talk about how good those stocks are. That's a conflict, sure, but no one minds it very much most of the time, because most of the time it is all more or less honest: The people own the stocks because they honestly think they're good, and then they go on TV to tell you why. When the world is terrifying, it is perfectly reasonable to both feel honest panic, and to want to go on TV to tell everyone why. Covid MAC We talked yesterday about SoftBank Group Corp.'s desire to get out of its agreement to buy $3 billion of WeWork stock at $19.19 per share. That desire is totally normal and understandable. SoftBank struck that deal back in October, when WeWork's business was a laughingstock, sure, but in retrospect basically fine; now it is March, and a global plague makes monthly rentals of individual desks in open shared offices a tough business to be in. WeWork is worth less than SoftBank agreed to pay for it, and SoftBank hasn't actually paid yet, so it would like to pay less. But instead of just straightforwardly saying that, SoftBank is telling WeWork shareholders that the problem is some regulatory probes. The reason for this, presumably, is that SoftBank's agreement with WeWork probably says something like "if we are doing anything materially illegal that we haven't told you about, you can get out of the deal," but it probably doesn't say something like "if there's a big virus, you can get out of the deal." So SoftBank is asserting the excuse that works, not the one that really matters. Meanwhile of course if you are a WeWork shareholder who has thought for months that SoftBank would buy your shares for $19.19, you especially want them to follow through now that everything has gotten worse. None of this is really unique to WeWork or SoftBank. There are lots of contracts, in the world. Lots of companies agree to buy other companies; lots of investors agree to invest in companies; lots of lenders agree to lend money to companies. Then the world intervenes. In general if you agree to buy or invest or lend before a global pandemic, and then a global pandemic hits, you will regret your decision and want your money back; if you are on the other side, though—if you're the seller or the borrower—you will be happy with the deal and really want to keep the money. Who wins? Here is a blog post from law professors Matthew Jennejohn, Julian Nyarko and Eric Talley about Covid-19 and "material adverse effect" (or "material adverse change") clauses in merger agreements.[4] MAE clauses basically say that, if something very bad happens to the seller's business between the time the merger agreement is signed and the time it closes, the buyer can walk away. A famous fact about MAEs for a long time was that no MAE had ever happened: In the rare cases when buyers tried to walk away from deals, claiming an MAE, courts would always basically say "no it's not bad enough" and make the buyers close or pay damages. (That has changed, but they're still quite rare.) MAE clauses are also full of carve-outs saying that basically any bad thing that anyone imagined, before the deal was signed, don't count as an MAE, which is part of why they are so rare: The basic sorts of bad news that you'd expect to give an acquirer cold feet, recessions or stock-market crashes or whatever, explicitly don't count as MAEs; the acquirer has to close anyway. What about Covid-19? Well, there are not a lot of merger agreements explicitly addressing Covid-19, but there's at least one. Morgan Stanley's agreement to buy E*Trade Financial Corp. lets Morgan Stanley out of the deal if there is a material adverse effect on E*Trade, but there are lots of exceptions, and one of them is "any acts of God, natural disasters, terrorism, armed hostilities, sabotage, war or any escalation or worsening of acts of war, epidemic, pandemic or disease outbreak (including the COVID-19 virus)."[5] Other merger agreements don't mention it explicitly. Some have exceptions for "pandemics," and one even has an exception for "plague," and I tell you what if I were still in the business of writing merger agreements I'd definitely be updating my template to exclude plagues. But most agreements don't mention pandemics specifically; some have general terms like "Act of God" or "calamity," but some don't. The professors' basic conclusion is that there will be a lot of lawsuits—"If you are an M&A litigator on either the plaintiff or defendant side (and you remain healthy over the next few months), your timing couldn't be better"—and I suspect that they're right, though I also suspect that a lot of the litigation won't be over the MAE clauses. It'll be like the WeWork/SoftBank situation; the acquirer will try to walk away from the deal because of the pandemic, but the lawsuits will be over whether some other clause—something about government investigations or accounting irregularities or sexual misconduct—lets the buyer walk away. Meanwhile in debt markets: Lawyers are calling it the "corona clause": new language that has cropped up in loan documentation giving borrowers more leeway to absorb hits to their businesses caused by the viral outbreak. Such terms could allow for lost revenues to be added back to calculations of profits, say analysts, helping companies to avoid breaching limits on how much they can borrow. Basically if you put in the corona clause, the borrower can keep the money it borrowed, though it still has to make scheduled interest and principal payments, which might be hard enough if its business is crushed. If you don't put in the corona clause, then effectively the lender can demand its money back when the pandemic hits: If Covid-19 crushes the borrower's business, its profits will be too low to meet the covenants in the loan, leading to a default. The corona clause doesn't suspend interest payments during the pandemic or anything; it just provides an "Ebitda add-back." The loan requires the borrower to maintain at least a certain level of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization and any other expenses the borrower negotiates to exclude; the add-back excludes some expenses (or, here, some revenue declines) from that calculation. The last few years have seen a lot of articles criticizing Ebitda add-backs, which, critics say, allow companies to borrow based on fantasies about their income rather than reality. "In a market that's already in danger of boiling over, aggressive attempts to make companies appear more creditworthy could be masking the true amount of leverage in the system — and the pain for investors if the loans go sour," said a Bloomberg story in 2017. A coronavirus Ebitda add-back is a particularly stark case of this: Basically, if a pandemic hits, your lenders will pretend that you had as much income as you would have had without the pandemic, rather than foreclosing on your loan based on your actual income. Your borrowing capacity is based on entirely imaginary earnings. As it absolutely should be! This is obviously good! We are rapidly entering a recession due to an exogenous and hopefully temporary pandemic; foreclosing on every loan to every company because they are facing months without income would obviously make things worse; the right thing to do is for lenders to suck it up and be nervous about the credit quality of their borrowers for a while until things get back to normal. The lenders ought to show a little team spirit here, and the corona clause forces them to. But you can always find complainers: However, the new terms creeping into loan documentation could be worse for investors in the debt, warned Ian Walker, an analyst at Covenant Review, as they could find themselves "holding the bag" at the end of the downturn. "It's highly problematic. You are basically just masking the problem and not dealing with it," he said. Yes right forbearance from lenders doesn't solve the underlying problem of revenue going down in a pandemic, but it's not like some other clause would! Revenue will go down in a pandemic! Forbearance from lenders does solve the problem of everyone defaulting on their debts in a pandemic, which is its own problem, and which makes all the other problems worse. People are worried about stock buybacks On the one hand there seems to be some political support for blaming buybacks for the coronavirus crisis. On the other hand, people are also worried that they've stopped: Some analysts worry that by putting programmes on hold, companies are removing a pillar that the stock market has come to depend on. Repurchases have helped to power a record run in share prices that hit a peak last month before a rapid tumble into a bear market. Fewer buybacks "could amplify the downturn", said Lee Spelman, head of US equity for JPMorgan Asset Management. "Corporate buyback programmes have been the incremental buyer of equities over the last 10 years — it's been an extremely important factor for the market." We talked up above about bailout proposals that would give companies money so they can continue paying employees, which strikes me as roughly the right approach, keeping up some financial normalcy even as reality is very abnormal. I have not yet seen any proposals that would give companies money so they can keep buying back stock. Working from home Here is a story about how Wall Street traders are facing pressure to come into the office to look tough and make money: Wall Street's blanket directives telling workers to stop coming in aren't as simple as they sound, especially for traders. One said he's facing pressure to be "a tough guy" who follows the unwritten wartime rules. If there's money to be made, the trader said, his bosses would want him in the position to make it, even if there's a healthier and more soulful message being broadcast by the bank's chief executive officer. It's the power of metaphor, man. "Wartime rules"? What? "You're getting out of a Mercedes to go to the New York Federal Reserve," Lloyd Blankfein famously told a colleague during the financial crisis, "you're not getting out of a Higgins boat on Omaha beach." Make the money at home and keep everyone safe. Though here is Bloomberg's Cynthia Koons on working from home with kids: So it goes in households across America where employees attempt to work remotely while managing children whose schools or day cares have been closed to prevent the community spread of the virus that causes Covid-19. Optimistic parents have created schedules with "academic time" and "creative time" to manage their children's time. They're also flocking to virtual learning programs that promise precious hours or even minutes of distraction. But just days into the new normal, many are already panicking over how to sustain round-the-clock child care and their workloads. ... At best, workers will see a productivity dip, but some may have to step back from their jobs either partially or entirely. This is, shall we say, a matter of more than academic or journalistic interest here at Money Stuff. In about two weeks this column might consist entirely of lyrics from "Frozen." Things happen Dollar Soars With Funds Liquidating to Withstand Virus Siege. White House Mulls New 50-, 25-Year Bonds to Finance Stimulus. Federal Reserve Board broadens program of support for the flow of credit to households and businesses by establishing a Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF). Treasury bill yields turn negative in sign of investor fear. Bridgewater Associates Performance Hit by Coronavirus. CFA Exam Postponed, With No Tests Until at Least December. JPMorgan to close 1,000 Chase branches due to pandemic. "Instead of asking for a slice of lasagna, they'll buy all of it. Then they'll buy all of our root vegetables." How South Jersey Keeps Muskrat on the Menu. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] Is it insider trading? In the thought experiment? My short answer is no, come on, you can always trade on knowledge of your own plans. My longer answer is, you know, if this was really your business model, you'd probably have a company with a bunch of people, and you'd want to be clear on who is allowed to use the company's information to buy the call options, etc., it is all a little squiggly but not of any particular practical interest. I have a still longer answer about the likelihood of insider-trading enforcement when you are buying, say, call options on the S&P 500, but again there is no practical need to get into that. [2] Or more strictly: If you own a company, and it has the propensity to maximize the joint profits of all the companies in the stock market combined, the way to properly align incentives is to also own all the other companies. [3] Super not legal advice and also, like, super duper hypothetical thought experiment. This is what I'd do if things happened like this, but they wouldn't. [4] In my idiolect I tend to think "material adverse effect" but also "MAC," I dunno. Most modern merger agreements seem to use "material adverse effect," but "MAC" is more pronounceable. [5] As is customary, there is an exception to the exception "to the extent that any such event, circumstance, development, change, occurrence or effect has a disproportionate adverse effect on the Company and its Subsidiaries, taken as a whole, relative to the adverse effect such event, circumstance, development, change, occurrence or effect has on other companies operating in the securities brokerage industry or the other industries in which the Company or any of its Subsidiaries materially engages." If somehow the pandemic destroyed E*Trade but left other discount brokerages untouched, I guess Morgan Stanley could walk away. |

Post a Comment