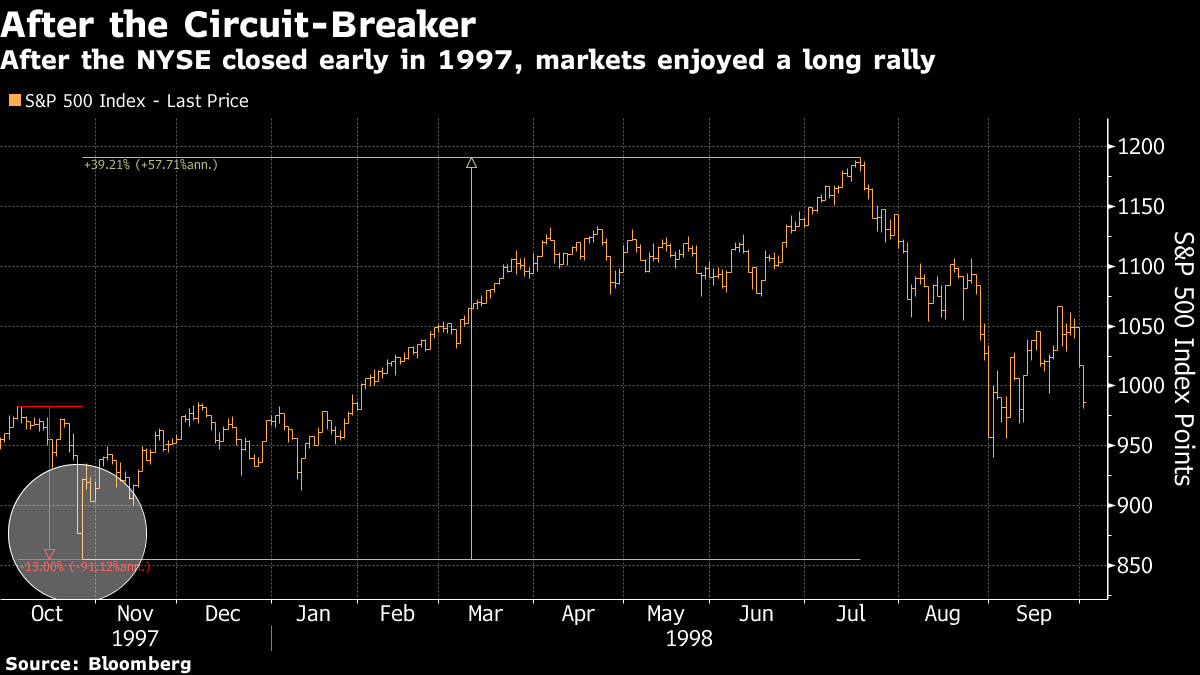

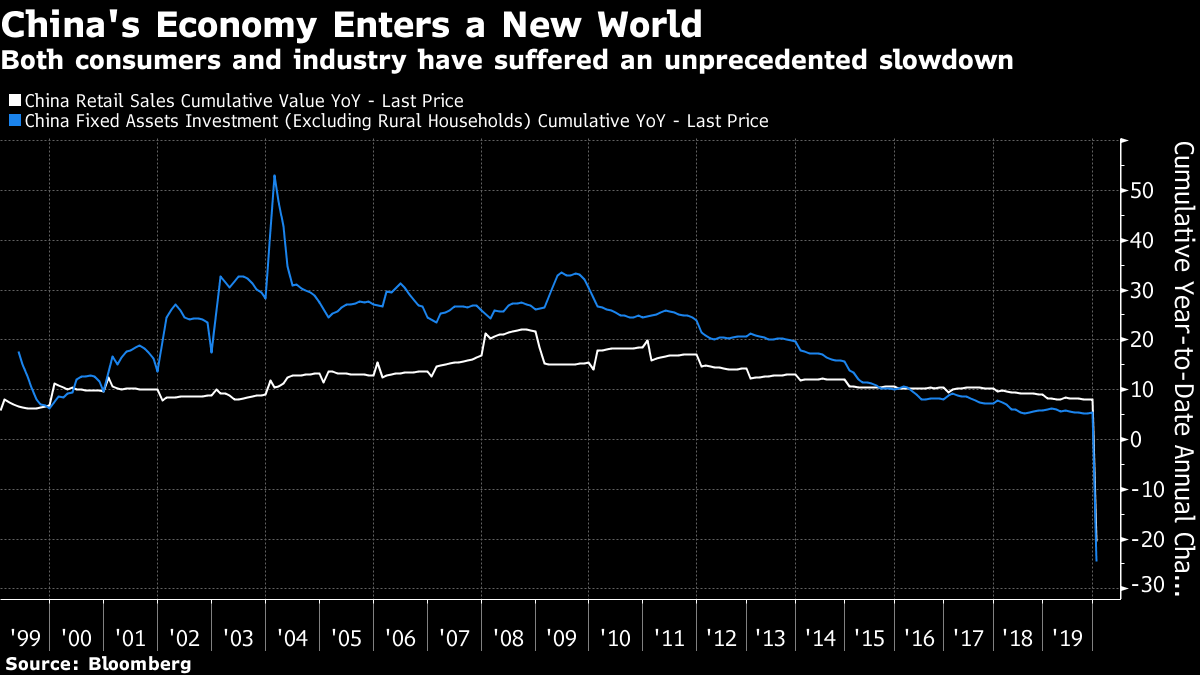

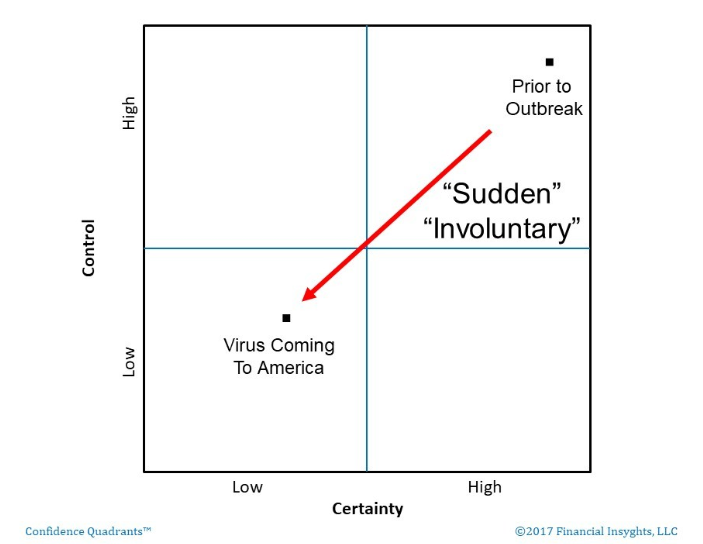

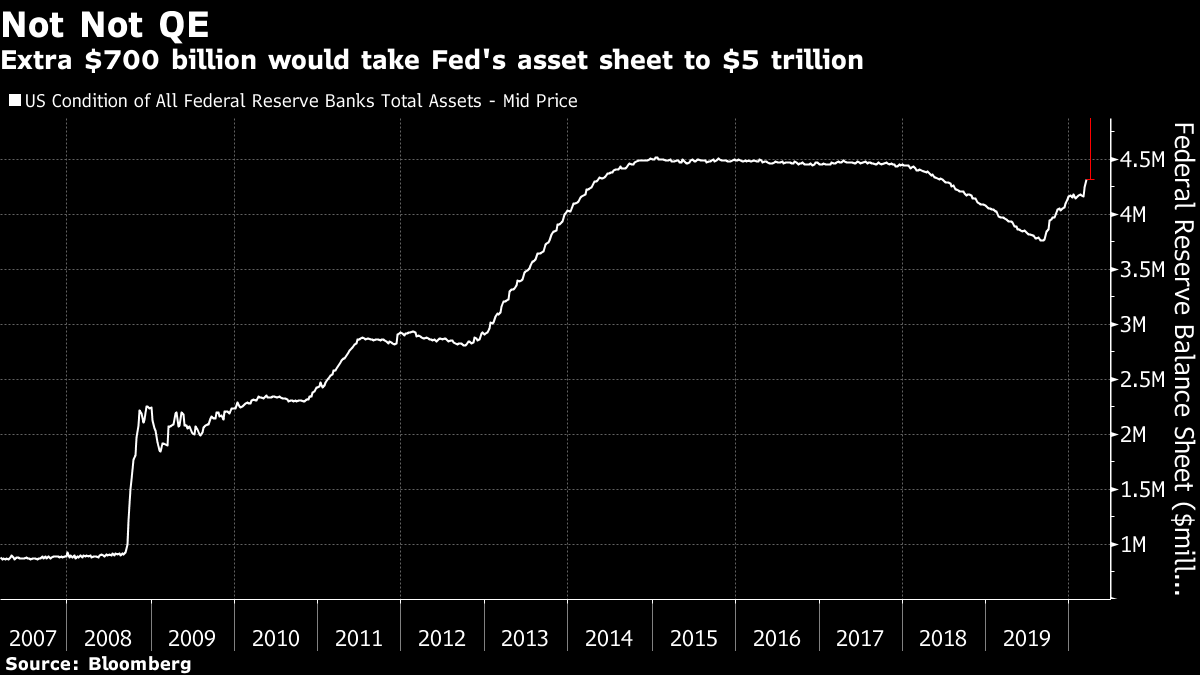

Time for a Break? No institutions in modern life have adapted social distancing more enthusiastically than financial markets. Thirty years ago, stock and commodities exchanges worked through large numbers of traders (mostly young and almost all men) gathering together in a confined space. Now, stock exchanges are quiet and dull places, with few people, and little noise above the slight hum of the computers. If any industry has already prepared itself for life under the coronavirus, it should be the capital markets. That said, many now seem attracted to the idea of closing down altogether. Circuit-breakers, rules requiring trading to halt for a while after indexes fall by a certain percentage, were triggered twice last week in the U.S. On both occasions they thwarted what had been vertical sell-offs. They didn't avert an extremely bad week, but they seem to have helped. Over the weekend, as the effect the coronavirus will have on life became ever more apparent, calls for a longer break became more audible. In my experience, this is new. People were horrified and dispirited during the credit crisis of 2007-09, and many predicted an outcome even worse than the one we got; but I don't recall any enthusiasm for simply turning off the machines. So, I will now set out as best I can the case for markets to be closed for a while. At the outset, I would like to make the following caveats clear. First, I'm not at all convinced of this argument myself — but I think it needs to be laid out. Second, it is still unlikely to happen, at least unless things get considerably worse. No administration would want to close the stock market. This administration, so proud of stocks' performance, really won't want to. Third, I continue to believe that markets are for allocating capital much as Churchill said of democracy for government — the worst way of doing it, apart from all the others that have ever been tried. The precedents Stock exchanges tend to stay open. In the last 30 years, there are only two examples of the New York Stock Exchange making an unscheduled closing. The first came in October 1997, when circuit-breakers introduced after the Black Monday crash were triggered for the first time, as traders belatedly tried to come to terms with the Asian financial crisis. At the time, there was a firm belief that circuit-breakers had been counterproductive. After heavy selling triggered the first halt in the early afternoon, traders were freaked out, and spent the pause filling out fresh sell orders. The market dropped like a stone as soon as trading reopened, and triggered a second circuit-breaker that forced the exchange to close for the day. The incident is little remembered now because retail investors took the opportunity to buy on the dip the following afternoon, and the bull market of the 1990s soon took off again with full force. The circuit-breakers might actually have done a decent job of interrupting a sudden cascade of selling. (Or, you could argue, they may have helped the market convince itself, incorrectly, that it was safe to take an already overpriced bull market up to the extremes it would reach in 2000):  The second time was after the 9/11 attacks of 2001, when the damage from the collapse of the twin towers made it impossible for the nearby stock exchange to function. Trading was aborted on Tuesday, Sept. 11, and didn't resume until the following Monday, by which time the scale of the damage, and of the government's fiscal and monetary response, was much clearer. The sell-off wasn't as great as many had feared, reaching 13% at its worst. By Oct. 11, the S&P 500 was back at its level from Sept. 10. Given the scale of the shock, which was as close as it could have been to many traders, this was a remarkably calm and orderly response. The 9/11 precedent is interesting. Then, as now, there was a true external shock. Nobody meant for the stock exchange to close, but it may have helped. Conor Sen of Bloomberg Opinion makes exactly this argument here. No great purpose would have been served by trying to trade during the dreadful days immediately after the attacks. Confidence was rattled. Information was scarce and likely to be wrong. There are two broad arguments for closing the markets now: Data Uncertainty about all the data that matter most to markets could scarcely be more radical. We don't know the eventual human cost, or the extent of the measures that will be needed, how long they will last, or how quick a recovery can be. Corporate earnings will unquestionably be lower than previously hoped. But nobody knows exactly where they will come to rest. Data published Sunday night U.S. time on Chinese retail demand and fixed-asset investment showed that on both sides of the economy the hit to activity has been truly staggering and unprecedented:  The U.S. and Europe need to know whether the economic hit will be as bad as in China, how long it will go on and how quick the recovery can be. Any attempts to put a price on stocks are just going to produce volatility, which sows confusion and ultimately creates disappointment. They will be guesswork. Take Friday, for example. U.S. stocks had their best day since Oct. 28, 2008. That produced some hope, but what happened next in 2008 shows that hope is likely to be dashed. From the end of that day, the S&P 500 still had to fall 29% before reaching a bottom more than four months later. Big convulsions are characteristic of a bear market, and they are likely to be particularly severe given the nature of this sell-off:  Psychology That leads to another reason to shut the markets down. Confidence is on the floor, and it is hard to see how it can get up again for a while. At such times, it might be best to make a clean break. Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts, who studies confidence in society and its effect on decision-making, maps confidence on a set of quadrants, with two dimensions — the sense of control over a risk, and sense of proximity. When a risk seems distant and under control from your perspective, as it seemed to Americans when the coronavirus was viewed as an epidemic in central China, then it can be ignored. When it seems hard to control and frighteningly close, confidence dips drastically:  Once in America, it needs to get close to home, and affect lifestyles. As I write, sitting in New York, the virus has now closed the city's schools for the next month, and restricted bars and restaurants to a take-out service until further notice. Nothing like this has ever happened before. It is hard to conceive of turning off activity as totally as the Chinese authorities managed in Wuhan, a city of about the same size. But this will come close. Measures like this have a potentially fatal effect on confidence. Atwater made the following prediction earlier this weekend, and I think it makes sense: In response to an imminent threat, people will try to now slam the door shut. Over the next several days, it would not be at all surprising to see all schools and most businesses close - likely the financial markets, too. And given what we have already seen in China, Italy and Spain, some kind of national shutdown appears to be inevitable. As we get closer and closer to that lower left-hand corner, and anxiety naturally spikes, leaders across the public and private sectors are going to respond aggressively. At the very lows, I expect that we will see widespread, dramatic capitulation - something akin to what we saw on 9/11, when the decision was made to ground every plane in the sky. Once we reach lows where people are sufficiently threatened and frightened, it may simply be desirable for markets to join in the shutdown. With the real economy effectively closed, there would be little to be lost, and potentially something to be gained. A Squeal of Covid-19 From the Fed Sunday evening commenced with a massive cut of 100 basis points in the overnight fed funds rate, bringing it back effectively to zero. That was coupled with an announcement that the Federal Reserve will buy another $700 billion in assets, which will bring its balance sheet up to $5 trillion, well above the $4.5 trillion at which it peaked at the end of the quantitative easing campaign.  Jerome Powell, the Fed chairman, made no attempt to deny that this was QE, saying merely that the labeling didn't matter. When I asked the Twitterverse to help him with a label, Philip Coggan of The Economist suggested SQUEAL — "Secondary Quantitative Easing Additional Level" — though my marginal favorite was Niall Ferguson's "QEVID-19." Whatever label we put on it, the move indicates deep concern among central bankers that liquidity in the vital Treasury bond market is drying up. A number of other measures show what worries the Fed. The announcement of swap lines with other major central banks to facilitate buying of dollars echoes measures taken after Lehman, and demonstrates concern that some currencies are taking a pummeling. Exhibit a) is the Mexican peso. The last thing the U.S. needs is a fresh crisis in the large nation next door:  The Fed also made clear its concerns about the mortgage market, and in particular the banks. Since the crisis, the governing philosophy has been to require banks to hold greater reserves of capital. The idea is that this should be contra-cyclical; banks should keep higher capital buffers in good times, and then be allowed to use them in bad times. This notion seems to have been taken to extremes, as U.S. banks will now be allowed not to have any capital buffer at all. That implies that the Fed is worried about a credit crunch, as borrowers have difficulty repaying loans amid an almost total shutdown. It is good that the Fed is taking action, but not surprising that action like this has scared the markets, with U.S. futures positioned for a renewed fall in stocks as I write. Another fascinating week lies ahead — assuming the markets stay open. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment