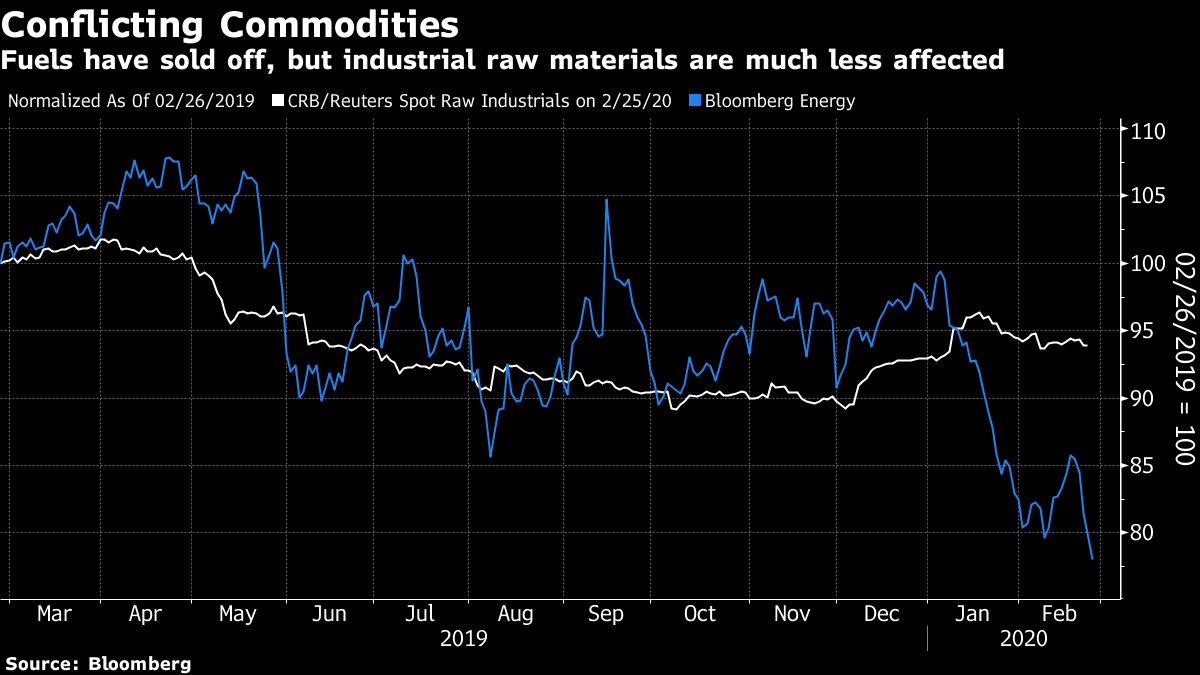

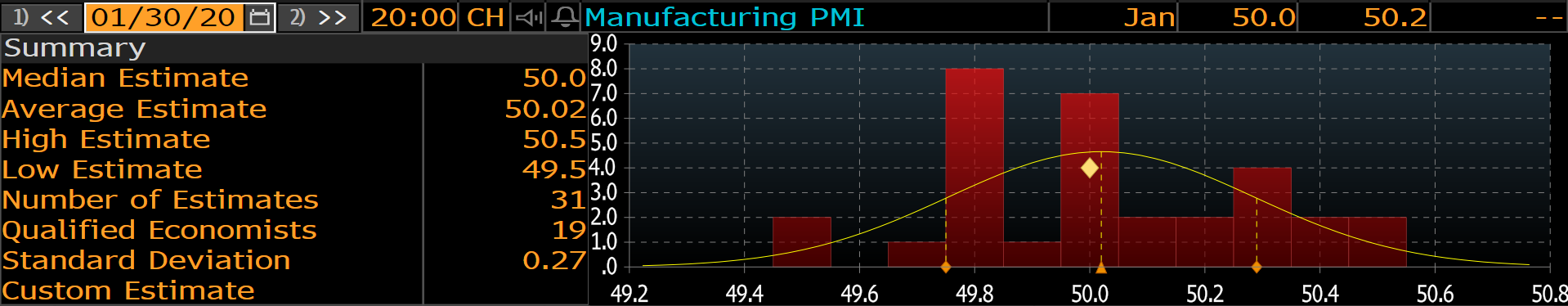

A Spreading Corona Another day into the saga of the attempt by politicians and investors to work out how to respond to the terrifying threat of the novel coronavirus, and the story remains the same. There is still no true panic in markets, and there is no attempt to correct the many imbalances that had built up before the virus started to take hold in the Chinese city of Wuhan. Instead, we continue to see a classic random walk in response to news. This doesn't mean that all is calm. The S&P 500 started the day in rebound mode. It went negative after a headline from a local New York radio station hit the wires, announcing that as many as 40 people in neighboring Long Island were suspected to have been infected. Closer examination revealed that none had yet been shown to have the virus, but the market damage had been done. There was also some brutal punishment for any confirmed case. Brazil announced that it had one, the first in South America, and its stock market had the worst selloff since the day in 2017 when its then-president was revealed to have been caught on tape negotiating a bribe. The punishment was specific to Brazil, and wiped out more than half a year's worth of outperformance of the rest of the region:  The news in China is relatively positive. The virus's rate of growth has slowed and it appears to be coming under some kind of control — even though there is still no clarity on the extent of damage to the economy. Market fears are now focused so clearly on the spread of the disease that stocks in both the U.S. and the rest of the world have now performed worse than China for the year to date:  This looks overdone. Even though these market ructions are plainly motivated by an attempt to discount the damage that will be caused, it is plain that some overshooting is happening. There is also some very wishful thinking. One suggestion doing the rounds on Wall Street was that stocks that benefited from people staying indoors would rise. Netflix Inc., scarcely an undiscovered gem, fit the bill, and rose in Wednesday's trading, even as hotels and cruise operators, which obviously stand to suffer, were sold. A "long stay at home/short going on vacation" trade would have generated about 60% so far this year:  To be clear, this looks wishful. Mass quarantining might not happen. If it does, then it's a fair bet that use of streaming services will rise. This won't necessarily help Netflix and its competitors, which earn their money from the number of subscriptions they sell, rather than from the amount that subscribers use their service. This isn't a broad market panic, then, but there is plenty of panicky behavior. This was predictable. Now that we know that SARS, Ebola and the other epidemics of recent years don't work as templates for this outbreak, we simply have no precedent to guide us. Gauging risks in such an environment is difficult going on impossible, and people will make mistakes. The uncertainty is so severe, though, that it will be hard to take advantage. The Story So Far For markets, the overriding issue is the economic damage wrought by the virus, rather than the human cost. We have a count of the victims and cases so far; there is very little hard evidence about the economic effects. That is about to change, and it could make for excitement at the end of this week and the beginning of next. As last year ended, amid great hope for U.S.-China trade relations, there was at least some evidence that the economy was perking up again. Since then, commodity prices — generally regarded as the market's first and most reliable sign of economic trouble — have been contradictory. Oil prices have taken a spectacular dive, after a brief swoon over the hostilities between the U.S. and Iran in the first week of January. Even so, the Reuters/CRB RIND index, which tracks spot prices of industrial raw materials, is still up for the year. No shock from Chinese demand has yet fed through.  That means that much will rest on the publication of Chinese economic data for February, which will start on Friday with the manufacturing PMI. The survey, in which numbers above 50 show expansion and below it show contraction, is about as good a leading indicator of the economy as we have, based on straightforward questions to purchasing managers about whether their volumes of business are going up, staying the same, or declining. As with virtually all Chinese data, they are subject to suspicion of manipulation. Since 2009, China's PMI has never gone lower than 49.0. But large tracts of the country have deliberately shut themselves down for much of this month, which must surely mean a bad number. The question is how bad; and then also, how bad a number the authorities will admit to. Put simply, nobody has a clue what the data will show, as some terminal screen-shots will show. This shows the distribution of estimates for last month's PMI, as polled by Bloomberg from 31 economists, on the eve of reporting:  The standard deviation of estimates was 0.27, and everyone agreed that the number would come out between 49.5 and 50.5. The outcome was exactly 50.

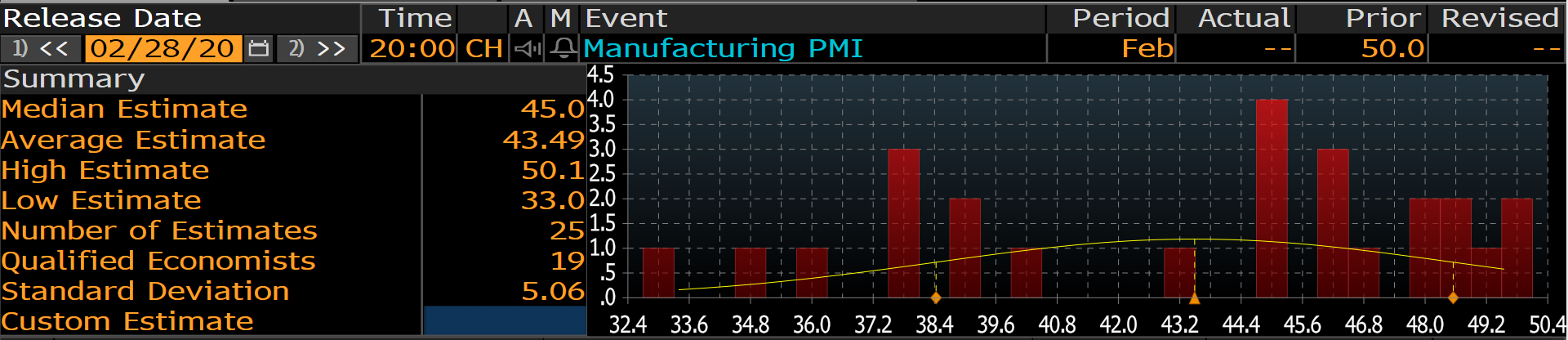

Now, here is the same exercise for the PMI number we will receive Friday:

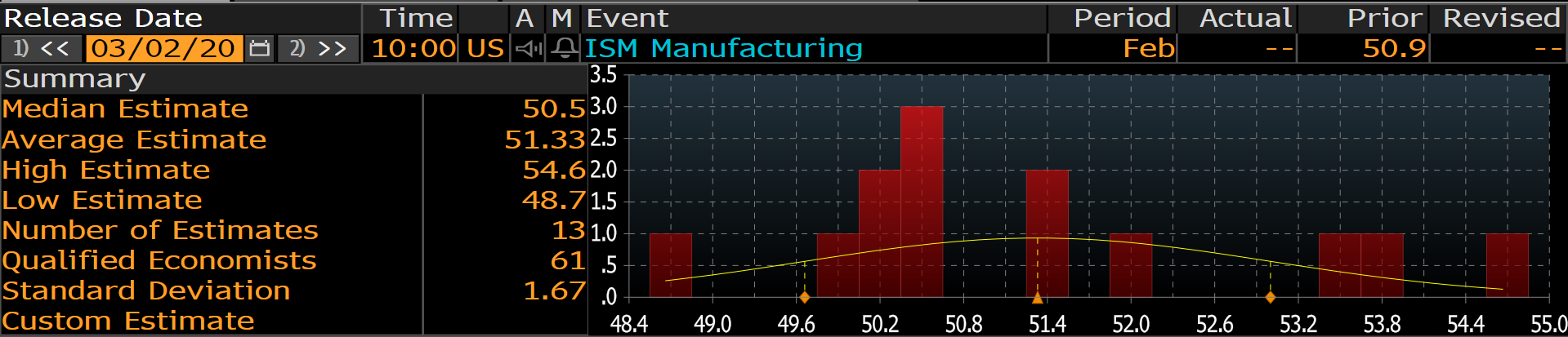

Of the 25 estimates reported to Bloomberg, the standard deviation is an astounding 5.06. Six of the 25 believe that the PMI will be below its all-time low of 38.8, set in November of the crisis year of 2008. That prompted China's historic fiscal stimulus. Meanwhile, two economists think that China will try to hold the line with a print of 50. With nobody really knowing what will happen, the most positive gloss we can put on Friday's announcement is that nobody will be very surprised. The sheer range of estimates hammers home the point that nobody yet really has a clue how much damage the virus has done to the Chinese economy. The uncertainty is affecting other economies. This is the same chart for the U.S. manufacturing PMI, which is due out on Monday, and for which Bloomberg has 13 estimates so far. They range from 54.6 to 48.7, with a standard deviation of 1.67:  For the previous month the standard deviation was 0.93. While the uncertainty isn't as radical as for China, the lesson remains the same; nobody really has any confidence that they know what economic effect the virus has had so far. As for the future impact, which is what markets really want to know, nobody has a clue. It is quite possible that markets are already over-compensating for the full extent of the eventual damage — but it is hard to see how anyone can know that. Political Contagion The virus may well have political effects, to go with the human and economic costs. Those political effects, in a U.S. presidential election year, could yet radiate back on to markets and the economy. For several months now, prediction markets, and polls, have shown President Donald Trump's chances of reelection steadily rising. This has come in tandem with a strengthening stock market. The chart compares the spread between Republicans' and Democrats' chances in the election, according to the Predictit prediction market, with the S&P 500. The two might affect each other; a strong stock market will make voters happier with the status quo, while good political prospects for Trump reassure investors, who were particularly alarmed by the brief ascendancy of Senator Elizabeth Warren last autumn. Now, we will discover which was cause and which was effect, because the stock market has taken a dive:  The presidential press conference on Wednesday evening showed that the virus was already becoming a political issue, even without a major outbreak in the U.S. The president evidently see this as a politically risky moment. If there is a major outbreak, we can expect the stock market to dive further, and the president's chances to fall with it. Incumbents take the credit and the blame for the state of the nation, even for those things that aren't their responsibility. Trump has taken the credit for a rising stock market and so would find it difficult to avoid the blame for a falling one. It is possible that within a week the avowedly democratic socialist senator for Vermont, Bernie Sanders, will have all but wrapped up the Democratic nomination. So any spread of the disease into American cities will likely be accompanied by a growing perceived probability that the White House will fall into the hands of a socialist. Markets are already on a random walk as they try to assimilate the medical risks. That walk could easily become far more volatile. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment