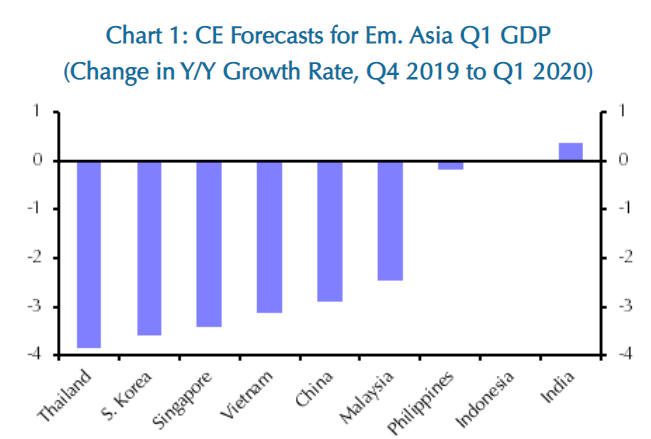

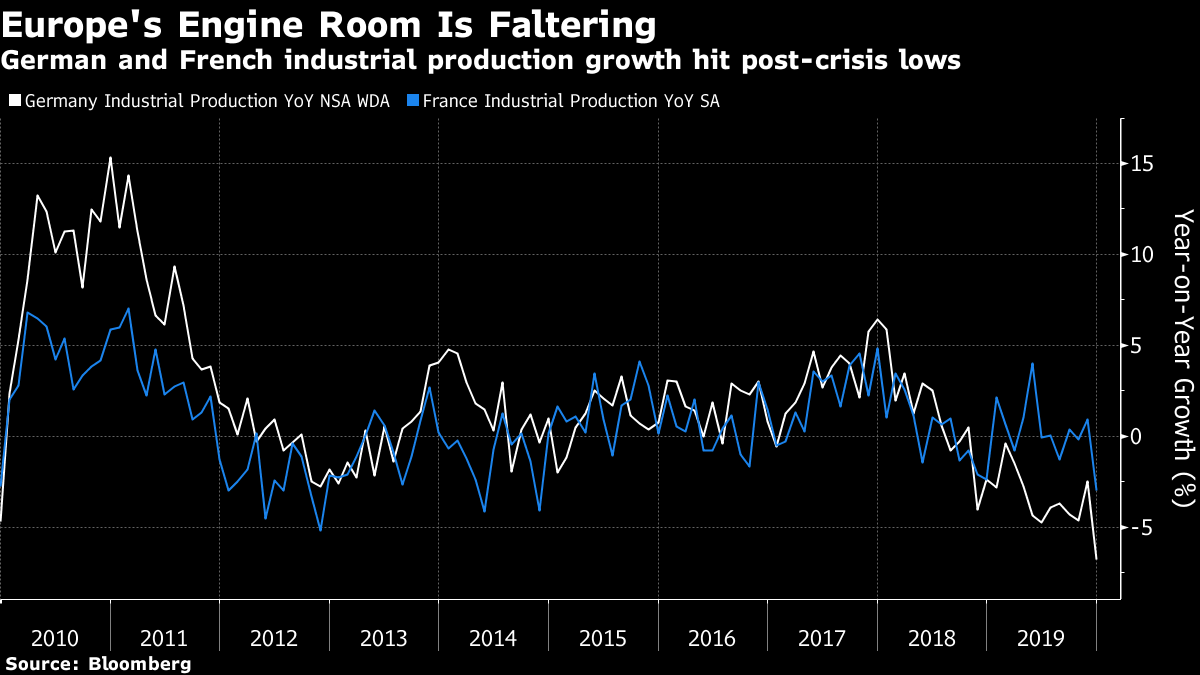

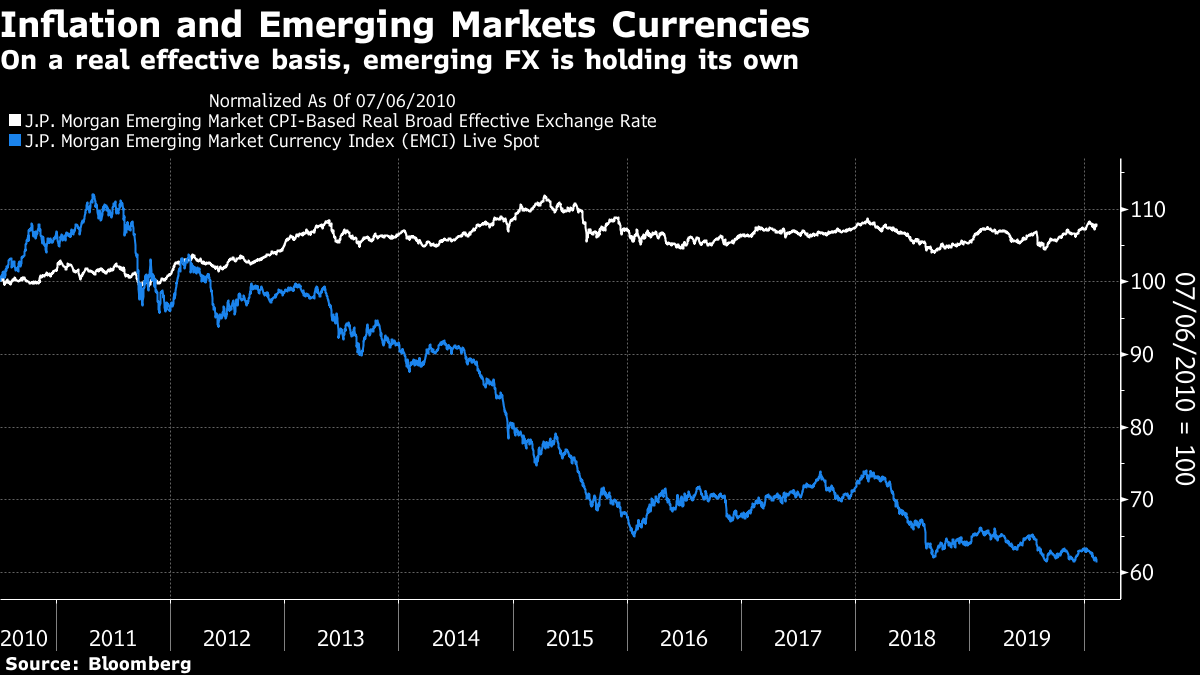

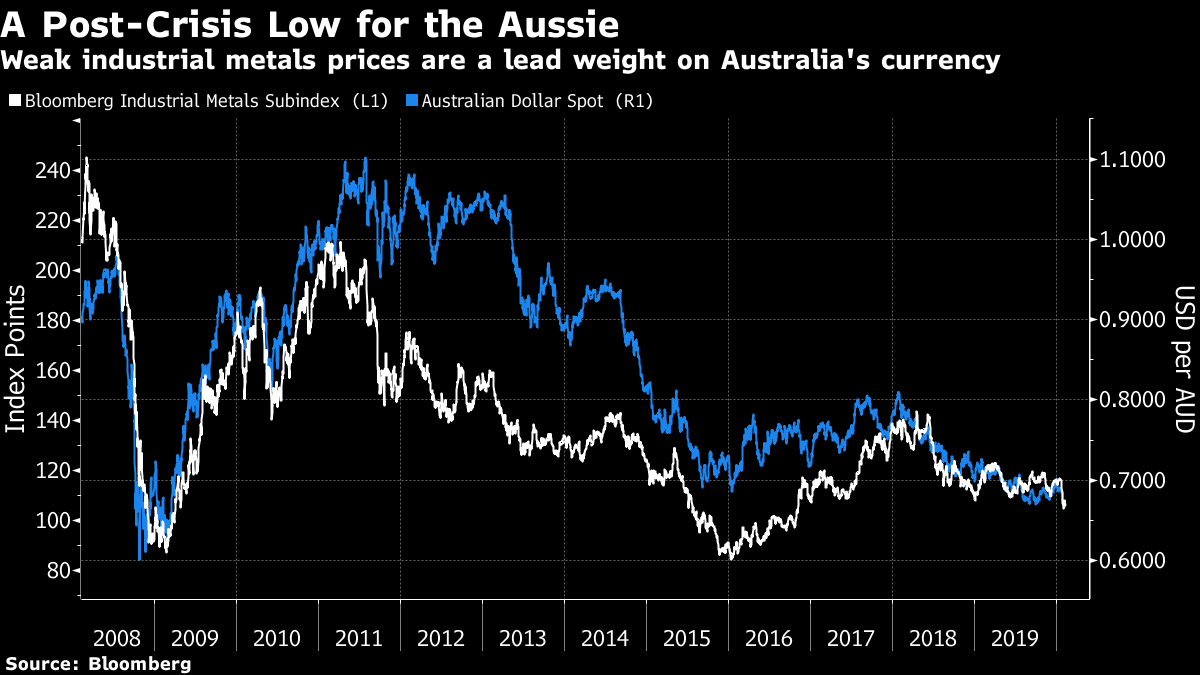

Dollars, Germs and Cents It's still unclear whether the coronavirus outbreak is coming under control. In human terms, the news continues to be dreadful, and to cast Chinese authorities in a negative light. But the data, to the extent that we can trust them, suggest the disease is spreading at a slower rate. That is positive, even if the death toll is now greater than for SARS 17 years ago. Assuming the spread is controlled, and we avoid an outcome in the "tails" of probabilities, such as a modern version of the Spanish Flu of 1918, we still have to confront the lasting economic cost. That may be great. An analogy with cancer treatment is in order. The medical profession is getting better at catching cancer early and saving lives; but the short-term costs of treatments such as chemotherapy, or surgery to remove tumors, can be very high indeed. In the same way that chemotherapy often has a dire immediate effect on the patients it will eventually cure, we need to look at the effect that measures to contain the coronavirus will have on China's economy. Pictures of cities with no people or cars are alarming. As China is the world's second-biggest economy, that means asking about the short-term economic health of the world.  The global economy has grown for 43 quarters in a row, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. At the end of last week, Capital Economics Ltd. of London became the first group of economists (to my knowledge) to forecast that the coronavirus will break that streak. This seems reasonable; China's measures will depress activity, and take time to reverse. That creates issues for economies across Asia.  Capital Economics' bottom line is that the coronavirus and its reaction will merely delay this year's global recovery, and that year-on-year (as opposed to quarter-on-quarter) growth will remain positive. But markets had been priced on the assumption that the recovery was ready to start already. It will be difficult for markets to process what will almost surely be the worst quarterly growth numbers in a decade. We also need to look at the patient's underlying health. Drastic measures have less of an effect on a healthy body, and become much riskier on a weak patient. Friday brought dreadful news about industrial production in the heart of the European economy. French and particularly German industrial production was falling sharply as the year ended. It was reasonable to hope that the easing trade relationship between the U.S. and China would help a recovery; it's now reasonable to fear that the coronavirus will postpone recovery for many months:  One optimistic take is that these developments increase the chance of more intervention by central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve. Indeed the pressure on emerging markets currencies is growing severe. On Friday, JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s widely followed index of emerging markets foreign exchange dropped to its lowest level since inception 10 years ago.  Much of the fall is the natural consequence of higher inflation in the emerging world. On a real effective basis, emerging currencies haven't lost much ground:  But weakening currencies have an impact. Latin American currencies now have much less inflation to deal with, which has brought lower rates and made them less attractive to carry traders. And the effect of weaker emerging market currencies, and a weaker euro, is a much stronger dollar. Despite the protestations of the president, who badly wants a weaker dollar, the U.S. currency is now stronger against the euro, and against a broad group of trading partners, than it was on the day he was elected:  China's measures to deal with the coronavirus can only exacerbate this. Look at the Australian dollar. Traditionally the most commodity-dependent of the major developed market currencies, the Wuhan-driven fall in metals prices has brought the Aussie to a post-crisis low:  We should all hope that the virus is indeed coming under containment. But it is growing clear that it will alter the international balance of economic power, at least for a while, through weaker commodities, weaker emerging markets, and a delayed economic recovery in Europe. A stronger dollar will mean lower profits and diminished competitiveness for American companies, and greater problems for countries that have borrowed in the U.S. currency. We might be paying the cost of containing the coronavirus for a while. Japanese stocks have set another nadir. The Topix index last week hit a fresh low compared to the rest of the world (represented by FTSE's index for the world excluding Japan). Since stocks hit bottom in the wake of the global financial crisis, the Topix has lagged the rest of the world by almost 40%:  Japan's deflationary stagnation had been a fact of life for more than a decade before the rest of the world lapsed into crisis. Its slow economy was amply priced in. And the country has avoided fresh crises while other parts of the world, most notably the eurozone, have suffered horribly. So why exactly is Japan performing so badly?

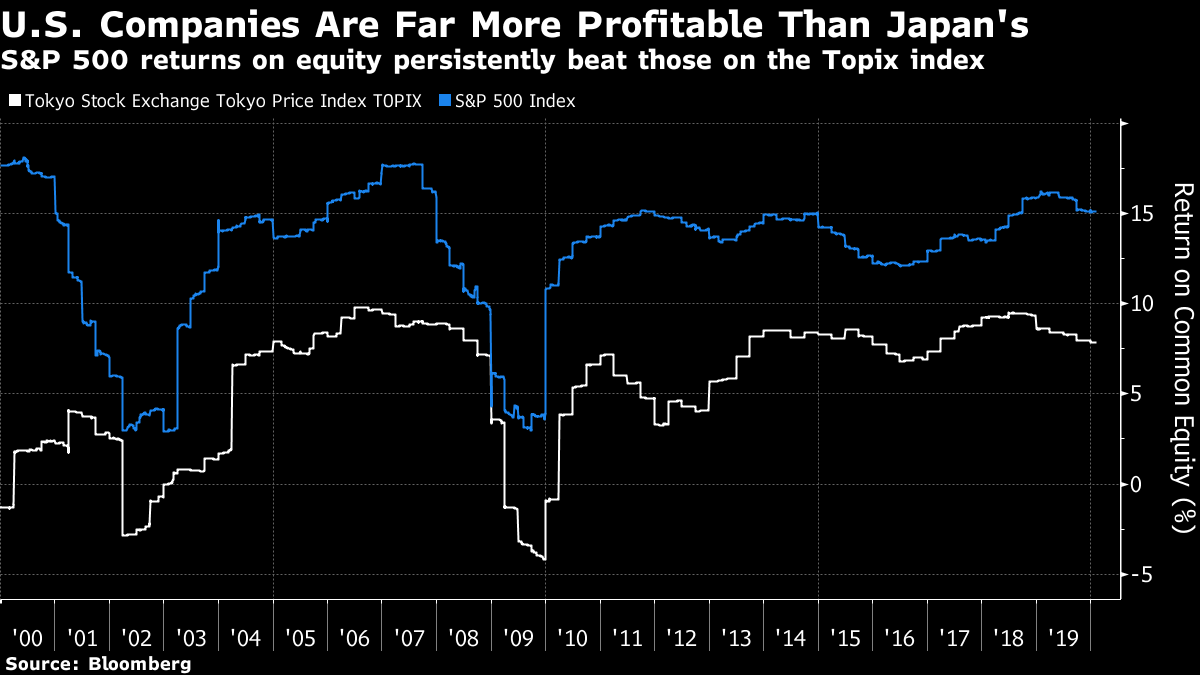

This fascinating piece by veteran Japan watcher (and optimist) Jesper Koll of WisdomTree Investments Inc. argues that the problem is the country is too competitive. Contrary to perception, Japan hasn't allowed its companies to consolidate and form into oligopolies, largely by making bids by shareholder activists prohibitively difficult. In the U.S., many industries are controlled by companies that enjoy monopoly (or at least oligopoly) rents. Certainly if we look at the profitability of S&P 500 companies compared to Topix companies, the gap is wide and persistent:

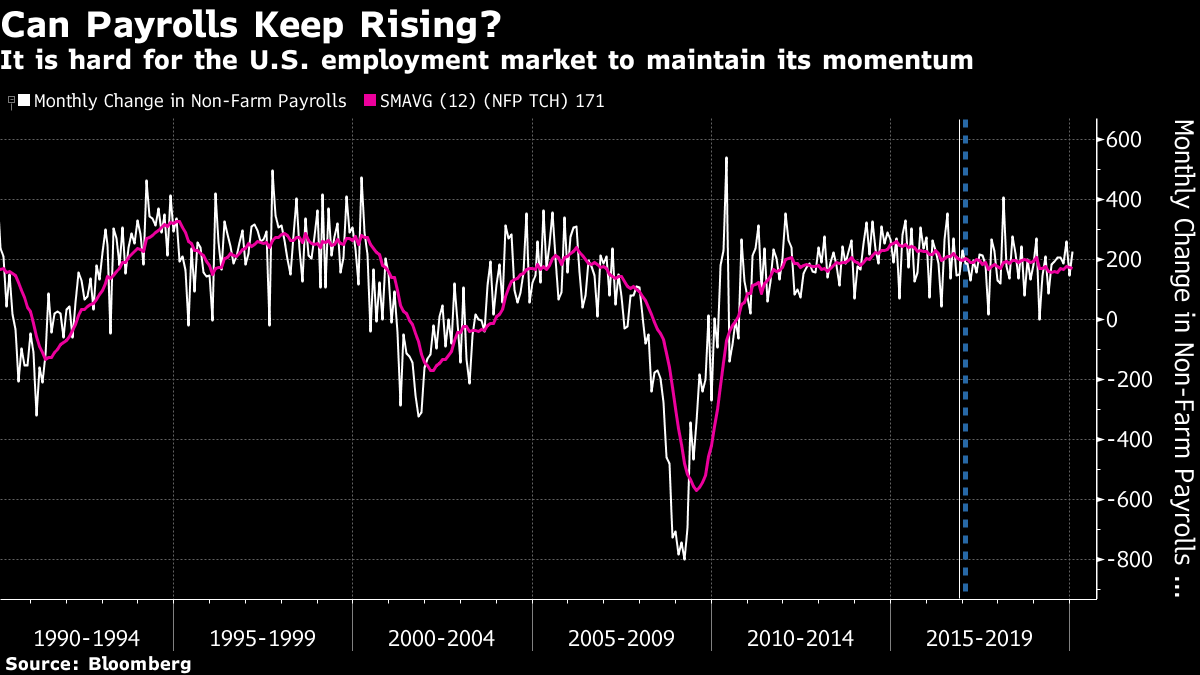

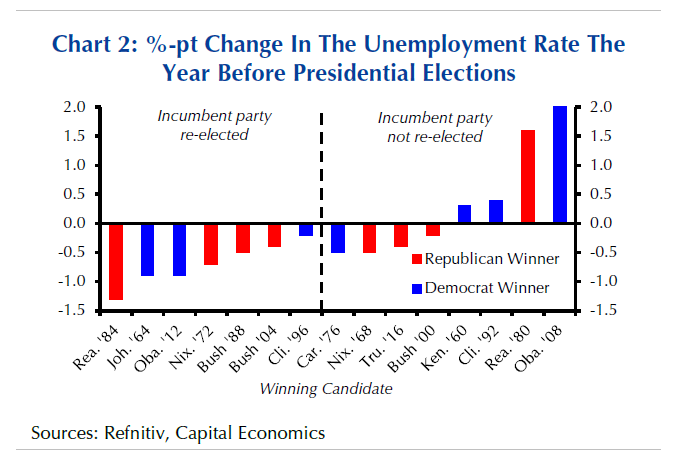

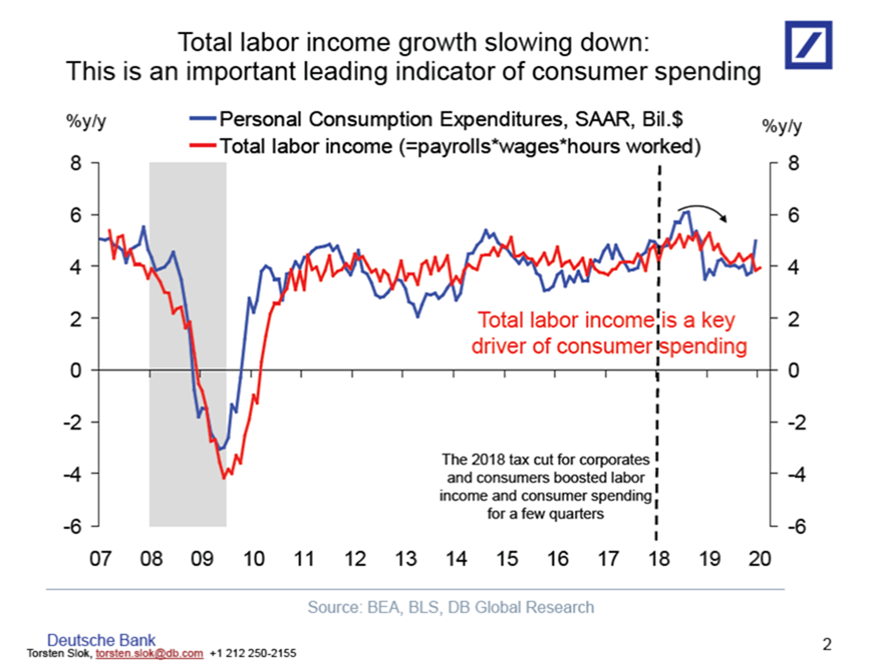

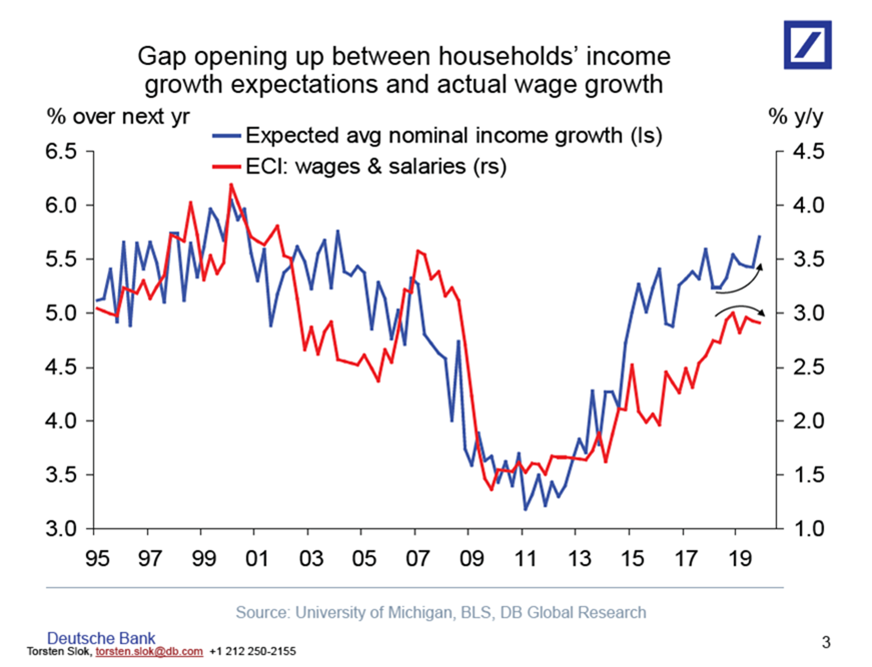

This might be because American companies are just fantastically managed, of course, but Koll argues convincingly that Japan is more serious about competition and capitalism — and that might well, in turn, mean that they deliver more value for customers and keep less in profit for themselves: Interestingly, over the past 20 years, Japan has become more competitive, while America has become more monopolistic or oligopolistic. Between 1997 and 2017, the market share controlled by the top four companies fell in Japan from approximately 15 percent to 11 percent. In the U.S., the top four domination rose from approximately 26 percent to approximately 35 percent over the same period. This is quite a gap. But with Abenomics, there is good news for shareholders in corporate Japan (and presumably bad news for Japanese consumers). Companies are under more pressure from investors to consolidate. Japan's dystopian shrinking demographics mean this might be the only way to avoid an ugly contest for the best talent. There are fewer good employees to go around; the best way to acquire them might be to buy their companies, Koll argues. Many Japanese companies are holding on to a sliver of market share but are barely even ghosts of their former selves. Eliminating them will raise profitability and returns. Maybe, just maybe, corporate Japan can start to give its investors a positive surprise. Trump Rampant Last week was by common consent the best for President Trump's political fortunes since he was elected. The Democratic mess in Iowa, combined with the president's acquittal in his impeachment trial, a positive and optimistic State of the Union address, a fresh record for U.S. stocks, and more healthy economic numbers reinforce the impression that Trump will probably win again in November. The best measure of conventional wisdom, arguably, is the prediction markets. They are far from perfect. You can tell this from the fact that Predictit now gives the Republicans a 56% chance of winning, and the Democrats 46%; they aren't perfectly efficient. But last summer there was a 15 percentage point lag for the Republicans, which has now turned into a 10 percentage point lead, and that plainly indicates the belief that Trump's political fortunes have strengthened greatly. If anything this understates the odds that many in Wall Street tend now to put on a Trump re-election. Trump's rising odds and the rising stock market have tended to reflect and reinforce each other. Very few investors are comfortable with the idea of President Bernie Sanders, and that appears now to be their most likely alternative:  Politics and epidemiology tended to flood out Friday's employment data. They were good, and have become an important plank in the president's plan to win re-election. But it may be difficult to keep this up. The following chart shows the monthly change in non-farm payrolls, going back three decades. It is hard to see that on this headline measure the advent of Trump in early 2017 had any effect on a very well-established trend. Indeed, the trend is perceptibly — albeit only very gradually — slowing:  This could matter a lot. Ronald Reagan famously posed a direct question to voters in 1980 and again in 1984: "Are you better off now than you were four years ago?" In practice, it appears memories aren't quite that long. Voters appear to ask: "What have you done for me lately?" If things are perceived to be getting better in the year before the election, the incumbent benefits. Since 1960, no party has held on to the presidency if the unemployment rate has risen in the last year of their presidential term:  With unemployment at a record low, the risk that it rises between now and the election is significant. At 3.6%, it is slightly higher than it was from September to December (3.5%). Broader indicators of the employment market suggest things are beginning to slow. This chart, from Deutsche Bank AG, shows total growth in income from labor is falling:  Prolonged prosperity also encourages greater expectations for the future. Growth in actual wages and salaries has leveled off; growth in expectations for those wages continues to increase. It would be politically difficult if these trends were to grow more accentuated over the next nine months:  Things do look very good for the president, and his opponents are in a mess. It would be absurd to say anything else. But it's easy to see how the perceived chance of a Trump defeat, or even of a Sanders victory, could rise. Richly valued markets would have difficulty dealing with that. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data- journalism based in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment