Keep Calm "If you can keep your head while all about you are losing theirs — it's just possible you haven't grasped the situation." Many of us might agree with Jean Kerr's revision of Rudyard Kipling's poem. Keeping your head while others lose theirs might be laudable, but it is often the wrong thing to do. In markets, which create their own reality, standing against the crowd can often be a very bad idea indeed. But what to make of it when markets seem determined to ignore something that everyone else finds terrifying, and for good reason? There was a very brief but very sharp reaction to Tuesday night's news of an Iranian retaliatory missile strike on two army bases used by U.S. troops in Iraq. But all it took was a presidential tweet that "all is well" and the brief response in Treasury bonds and gold — the two classic safe-haven assets — was reversed. And on Wednesday, once President Donald Trump had gone on to give a disciplined statement in which he appeared to de-escalate the situation and declined to threaten further reprisals, both assets moved to be weaker than they had been before the news of the missile strike:  Meanwhile, the S&P 500 Index opened the new year by setting a new all-time high and continuing to surf on a wave of optimism, with only a brief leg down on last week's news of the U.S. killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani. Somehow, it even managed to regain its high from Jan. 2 after Trump's Wednesday press conference:  As can be seen then, there were immediate reactions to the shocking events in Iraq, but in the greater scheme of things they were relatively muted. Does this show cool, if cold-blooded, judgment — or dangerous complacency? I am nervously inclined to come down on the side of the former. None of the events of the last week directly affected the supply of oil, which is the reason the Middle East matters most to markets. Iran's choice of a retaliation that didn't target oil was almost good news, at least from the point of view of markets. The most alarming scenarios — a major Iranian-backed terrorist attack on American or European soil, or a full American land invasion of Iran — always remained as very low-probability "black swan" events. And with the risks of such things so hard to gauge, there was little point trying. Therefore, while "World War Three" trended on Twitter, the more measured market response — that on balance, such an outcome was still very unlikely — made more sense.

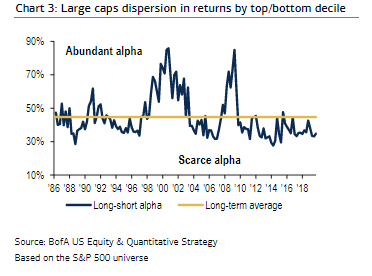

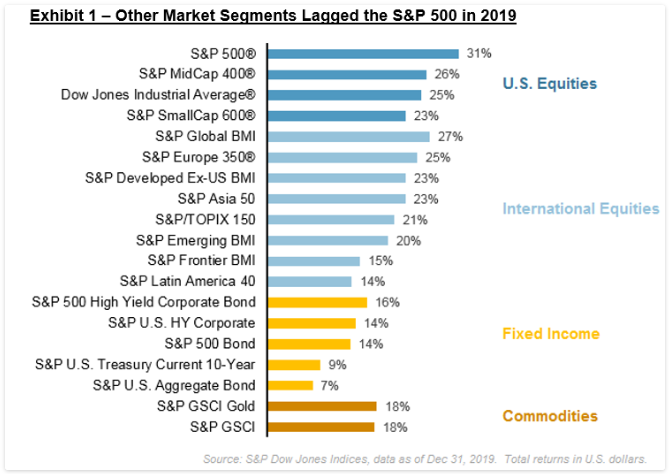

This doesn't mean I am totally confident the market has this right. To assassinate the second-most-powerful man in Iran was to take the long-running conflict between the U.S. and the Middle Eastern nation to a new and more dangerous level, and it is far from obvious that Iran will do no more in the way of reprisals. Wednesday afternoon, in fact, brought new reports of rocket attacks — this time in Baghdad's Green Zone — which caused risk assets to trim some of their gains. Risks in the Middle East indubitably remain higher than they were a week ago. And there are plenty of other things to worry about as well. But this still looks like a rare occasion when the market is right to be cold-blooded. For Active Managers, It's Just Not Fair As Donald Trump rose to make that statement on Wednesday, nobody knew what was coming next. And that in itself highlighted the painful problem for professional investors. Their claim to have a superior ability to manage people's money in many ways boils down to a claim that they have an informational advantage. Active equity managers spend their lives crunching through company reports and interviewing managements, leaving them with a far better grasp of whether companies can really perform than the rest of us. But these days, much is driven by broader macro trends that in turn, as we have just seen, can be driven by the latest words from President Trump's mouth or Twitter feed. That means nobody has a truly useful informational advantage unless they know what he is going to say next — which is to say that nobody does. Small wonder then that life remains so difficult for the many hedge funds who endeavor to make money by calling macro conditions and moves between asset classes better than anyone else. But the misery also continues for conventional active equity managers. We all know that their task of beating market benchmarks grows ever harder as the weight of institutional money moves into passive funds, which enjoy the critical advantages of low overheads and minimal trading costs. Last year turns out to have been particularly brutal for active managers. One good reason for this was covered by Savita Subramanian, quantitative strategist for BofA. An active manager's chance of beating a benchmark by enough to cover their fees grows with the degree of dispersion between different stocks' returns. If there is a wide gap between winners and losers, then there is more of a risk of badly losing compared to the index — but at least it should also be easier to beat the index if you make the right choices. Last year, dispersion was unusually low, making it harder to beat the benchmark:  Chris Bennett, of S&P, offered a litany of further problems for active managers in S&P's Indexology blog. He pointed out that stock selection within the S&P 500 was "handicapped" by the fact that the five biggest stocks made an average gain of 51%. "Since few active managers (and few factor indices) allocate as much to the largest companies as the benchmark does," he said, "when the very largest stocks outperform, stock selection becomes harder." No active manager would be comfortable overweighting a company that is already a major share of the index. A further problem was that the largest sectors of the S&P 500 also outperformed their smaller peers. Just matching the benchmark already required having a bigger weight in information technology than anything else. As this sector gained more than 50%, it grew very hard to beat the index without having a very large weighting to technology. For those who wanted to go beyond U.S. equities in search of better value — which certainly seemed like a good idea at the start of last year, and also looks good now — the problem was that literally no major asset class anywhere on the planet did better than the S&P 500. This is from the Indexology blog:  For the record, three of the world's 94 primary equity indexes as defined by Bloomberg managed to beat the S&P 500 last year — and good luck to any fund manager trying to explain to clients why they had decided to leave the U.S. and put money into Greece, Russia or New Zealand.

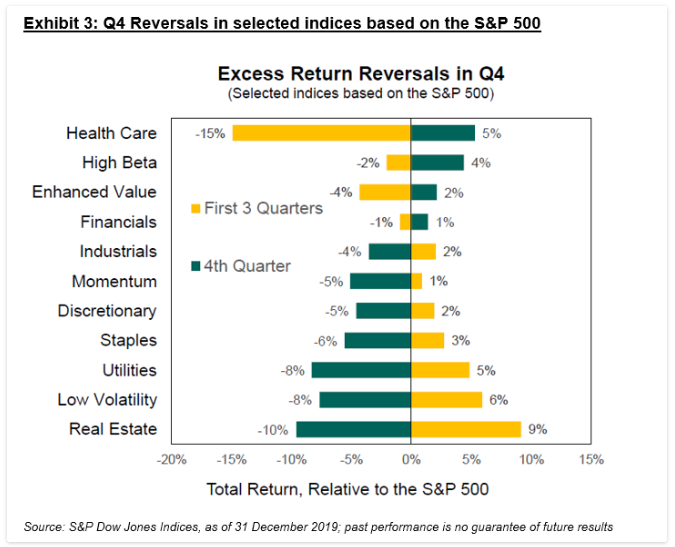

A final nightmare for active managers was that 2019 proved to be a year when you had to get your timing right and ideally make a big shift in the last quarter. Anyone who belatedly jumped on the bandwagon of the sectors that had performed well at the beginning of the year stood to be embarrassed. Markets wobbled lower in the third quarter after Trump intensified the U.S. trade conflict with China, while investors worried about the success of the campaign of Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. In the fourth quarter, there was a series of reversals. Health-care stocks started to beat the index, while a number of more conservative sectors — including staples, utilities and low-volatility stocks — that had prospered when people were worried started to lag the index badly as optimism returned:  Active managers, then, had a luckless year. The mathematics dictate that most of the time, most active managers will fail to beat the index after fees — but this was a year when that proved exceptionally difficult. Beyond that, the active management community has one very legitimate gripe. It is only human to divide the world into calendar increments. It is customary to take stock at the end of each calendar year, but this doesn't help individual investors, and it certainly doesn't help the managers bidding to run their money. There are plenty of sensible strategies that have a good chance of beating the market in the long term, but they involve making concentrated bets on a few companies that are true bargains, and having the patience to wait for the rest of the world to see the value in them. Managers investing money this way might well be doing so very successfully for their clients, even if they under-perform the index for a few calendar years. As we are human, and hot-wired to think in terms of calendar years, let's just agree on two things: - We can give active managers a mulligan for their dreadful 2019; and

- If they perform this badly again, we may not be so forgiving.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment