And yet. And yet. And yet. The Federal Open Markets Committee of the Federal Reserve completed a meeting Wednesday, and made a statement about it. Then its chairman, Jerome Powell, gave a press conference. Only those with a deep interest in monetary economics can possibly have found it very interesting. My colleague Tom Keene described the statement as a "nothingburger snoozefest" after it came out, and the word "nothingburger" recurred in many of the emails of snap analysis I received about the meeting as the afternoon progressed. The headlines: - The Fed did not change its main target interest rate, the Fed Funds rate.

- It didn't change its program of intervention to support the repo market. Powell also made clear that the program will continue into the next quarter, and didn't embark on any discussion on how to exit from it.

- The central bank did make a widely trailed change of 5 basis points to the interest it pays on excess reserves in a bid to keep the fed funds rate closer to the top of its target range.

- Its statement changed a total of three words compared with the one that accompanied the previous Fed meeting. Those three changes: It is now "returning to" its 2% inflation target, not "near" it, and the Fed says household spending growth is "moderate" not "strong."

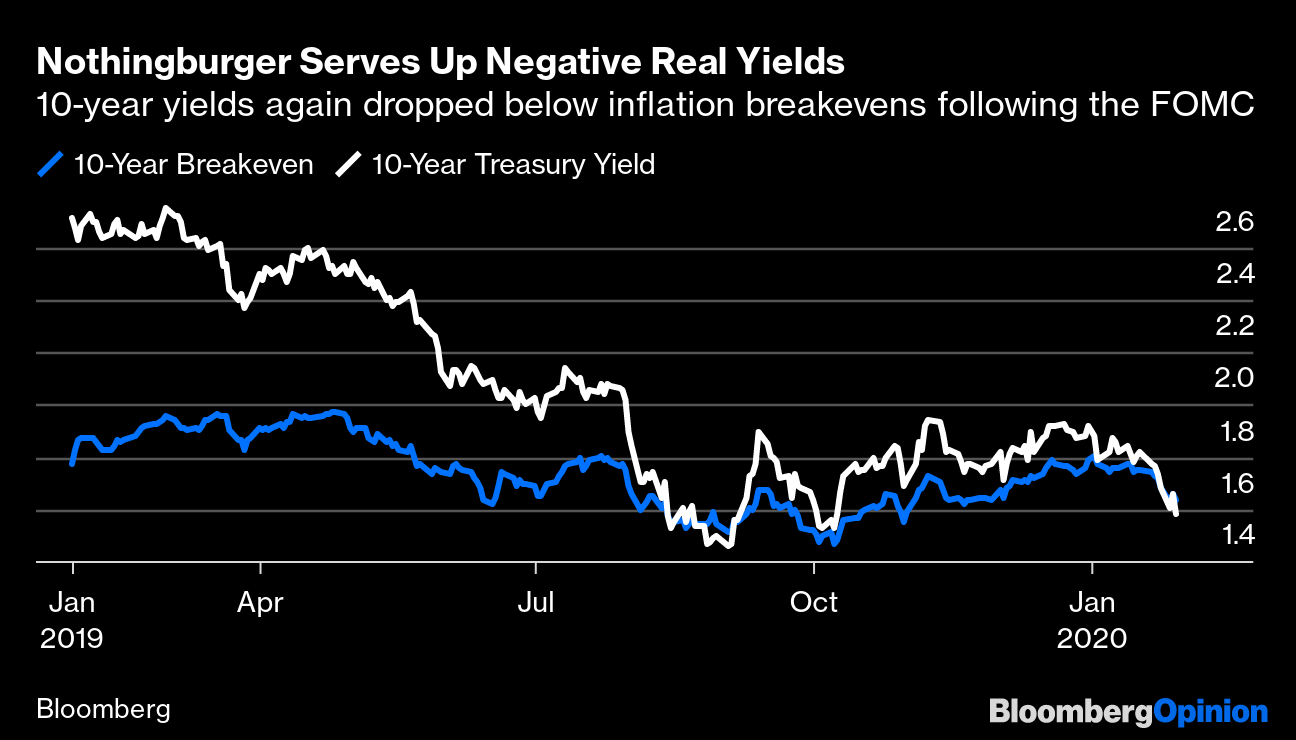

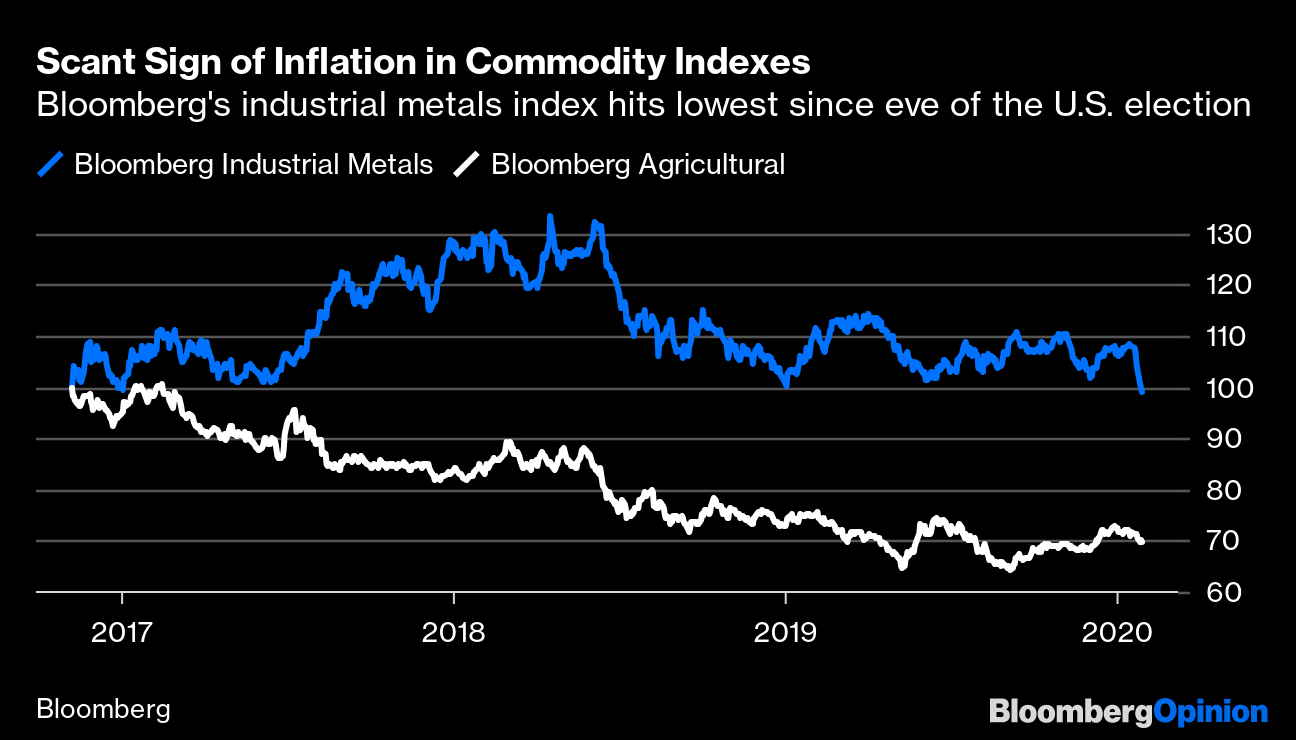

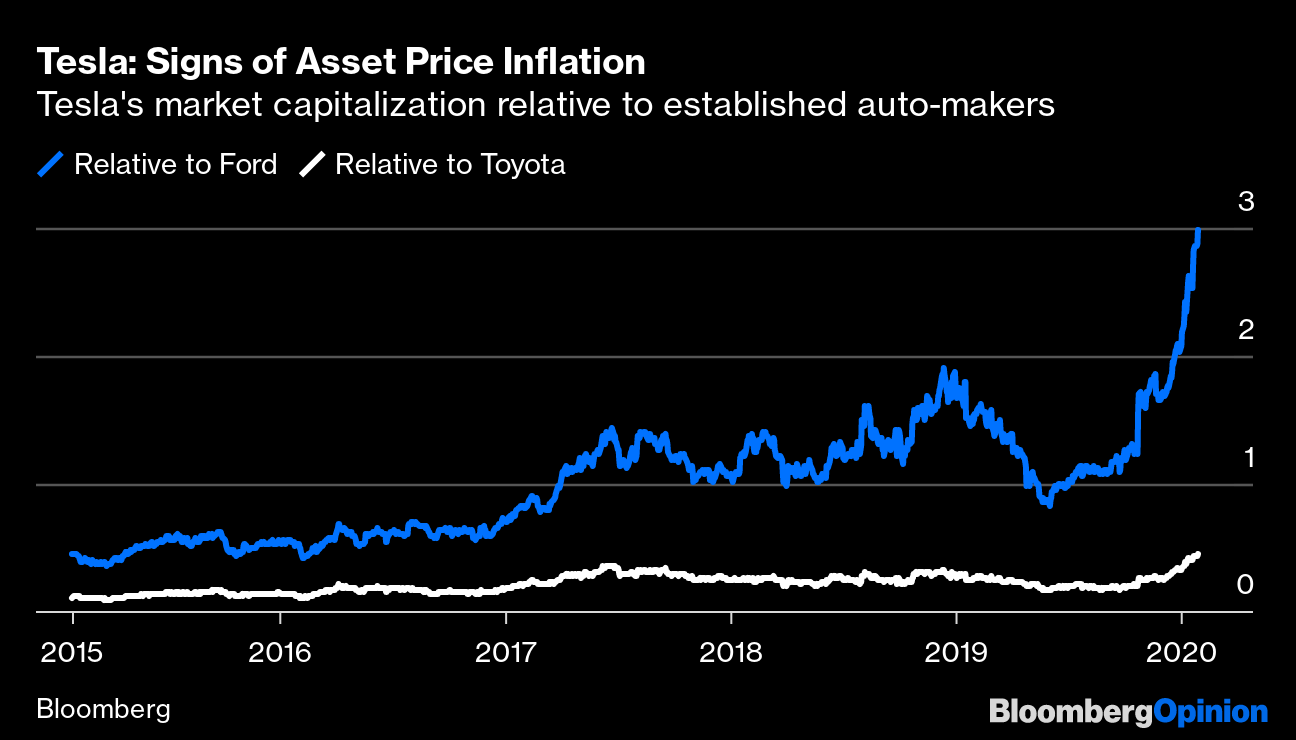

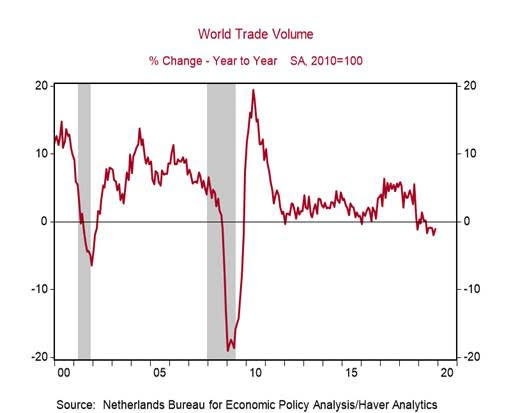

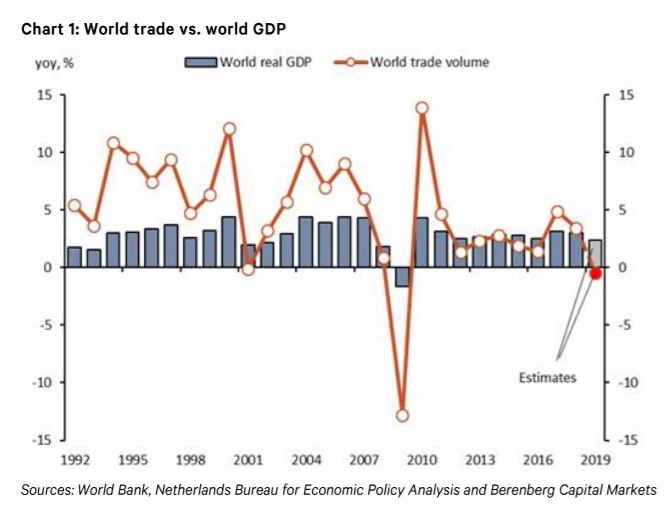

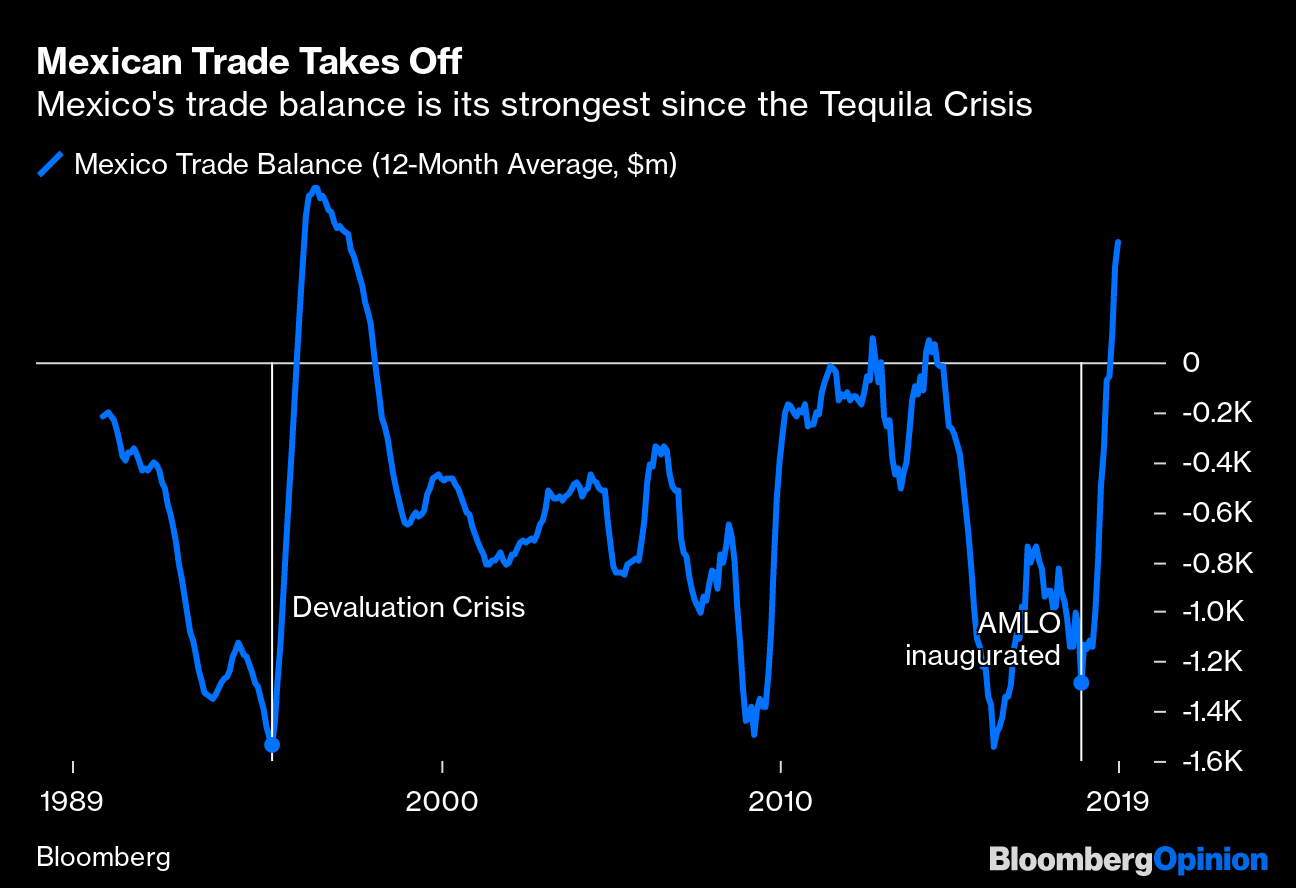

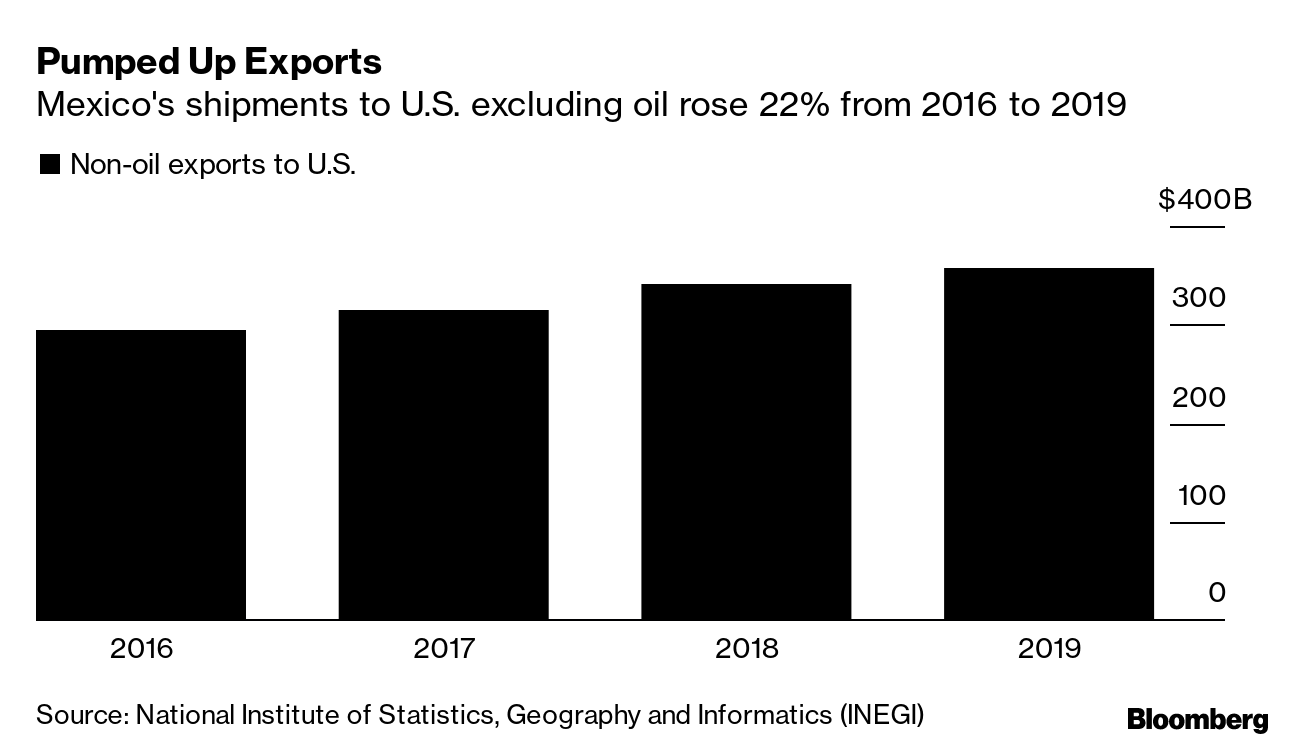

These are very important technical details that have little effect beyond the world of money markets, and — it has to be said — it was all pretty dull. On balance, the Fed seems more worried about low inflation than it was before, which implies rate cuts are a tad more likely. And that's about it. In my experience covering FOMC meetings, I can only think of one that was duller. That was the meeting overseen by Ben Bernanke in May 2006. Arguing against the May '06 meeting is the fact that the FOMC did on that occasion raise its benchmark rate by 25 basis points, which on the face of it is much more interesting. But it had raised rates by exactly that amount at every meeting for more than a year, in a policy begun by Alan Greenspan to ensure that the market never suffered a shock. Meanwhile, it only made one change to its statement, which was to add the word "yet." And somehow, I managed to write an 800-word column about the possible meanings of the word "yet," which is why that meeting is particularly burned into my brain for tedium. You can read that column here, if you are in need of help getting to sleep. However, we should never ignore the Fed completely. Back in May 2006, it seemed truly to be on autopilot. But we now know that U.S. house prices were about to peak in the next month, while credit markets were boiling up. By making life so predictable for markets, the Fed had created the conditions for complacency and excessive speculation. And this time, the ever so slight indications of dovishness from Powell were enough to move markets. According to the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function, the chance of a cut in June almost doubled on Wednesday, to 52% from 28%. And on balance the market now thinks two cuts are likely over the next 12 months, compared to only one yesterday. If we look at the bond market, we can see that real yields are negative again, with the 10-year yield dropping below the breakeven rate of expected inflation. These are exceptionally easy monetary conditions:  We also have a dreaded yield curve inversion once more. The whole of the curve flattened, with the five-year yield dropping slightly below the two-year, while the key three-month/10-year relationship inverted during Asian trading. This is as good a recession predictor as exists, and it isn't going away. That in turn increases the pressure on the Fed to keep cutting rates, and expanding its balance sheet — which will continue to convince many investors that There Is No Alternative (TINA) to stocks. This dose of dullness from the Fed need not yet have the calamitous consequences of the May 2006 meeting; but it could yet happen. Inflation: Some Contradictory Signs On the subject of inflation and the risk of more of it, Wednesday brought some contradictory news. First, looking to the commodity markets, Bloomberg's index of industrial metals dropped to its lowest since November 7, 2016 — which happens to be the day before the last presidential election. For the first time, industrial metals have lost value during the Trump presidency. Meanwhile, agricultural prices continue a steady decline. From the commodity markets, then, there is no sign of inflationary pressure, and no sign of any great demand in the world economy. Raw materials are growing cheaper.  Then we come to asset prices. Tesla Inc. announced its results after the market closed, and was rewarded with a pop of more than 6% in after-hours trading. Its share price had already doubled in the three months since its last quarterly results, inflicting immense pain on the doubters who had sold Tesla short. The stock is now on course to treble from a low last summer. To put this in perspective, the following chart expresses Tesla's market value as a proportion of Ford Motor Co.'s, and of Toyota Motor Corp.'s. It doesn't include the after-hours reaction to the Tesla results:  If the after-hours rally holds up on Thursday, Tesla will be worth three Fords for the first time, and also half a Toyota. These numbers bake in a great deal of optimism. In summary, it looks as though the Fed should indeed be worried that inflation, as conventionally measured, will drop well short of 2%. But when it comes to asset price inflation, the risk is the reverse. The Fed should probably be more worried about the latter than the former. For almost two years now, there has been a tendency to look at trade as a tale of almost binary outcomes. Will the U.S. and China go to war over trade? If they do it is bad for everyone, and if they don't it is good for everyone. That is a caricature of the common position, but some recent evidence gives much clearer context of potential winners and losers. First, and most importantly, world trade volumes are falling consistently, in a way they haven't done since the Great Recession. There is something to the notion that everyone loses from the trade conflict of the last 12 months:  This is concerning as trade tends to correlate with global GDP, as this chart from Mickey Levy, chief U.S. economist of Berenberg Capital Markets, makes clear:  The CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis has an excellent interactive trade monitor website, which you can find here. It is well worth going there to explore trading trends briefly (or to get very granular you can go to the MAPS function on the terminal and watch freighters and tankers as they move around the world). The Bureau's data show that Eastern Europe and Russia has been unscathed with a 4.2% growth in trade volumes from a year earlier. Latin America (-4.3%) and Africa and the Middle East (-4.6%) have been the worst hit. Even this conceals some big differences. Mexico's trade balance has just taken off dramatically. The following chart shows the 12-month moving average for its trade balance with the rest of the world, going back to 1990. Contrary to popular belief in the U.S., the Nafta trade agreement was not enough to give it regular trade surpluses. But the improvement over the last year is the most dramatic since 1995, when trade was buoyed by the devaluation crisis of late 1994.  It has done this largely by being the counterintuitive winner from the U.S.-China trade conflict. The manufacturing businesses massed at the U.S. border lost much business after China's accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. Now, with tariffs applying to Chinese goods, American importers are returning to Mexican suppliers. The following numbers show that Mexican non-oil exports to the U.S. have risen by 22% since 2016, the year before the arrival of Donald Trump.  These numbers are all the more impressive for being achieved despite a sharp gain in the Mexican peso since its current president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (known as AMLO for his initials) took office in December 2018. U.S. dollar investors have made a 16% profit on Mexican peso carry trades since then, while the currencies of other Latin American countries, and other similar emerging markets, have inflicted losses:  Part of this can be attributed to the scare ahead of AMLO's taking office. He was widely regarded as a dangerous left-winger, and has so far proved more pragmatic than expected in office. He was even praised by President Trump during the signing of the new USMCA trade agreement, which has allowed Mexico to avoid another potential bullet. But the situation remains precarious for AMLO. A lasting U.S-Chinese peace could be disastrous for Mexico, even if it helped much of the rest of Latin America, which has been suffering from lower Chinese demand and lower prices for its commodity exports. The trade conflict is already creating some unlikely winners and losers. But mostly it has created losers. A few more unexpected twists and turns could reverse the gains for winners such as Mexico. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment