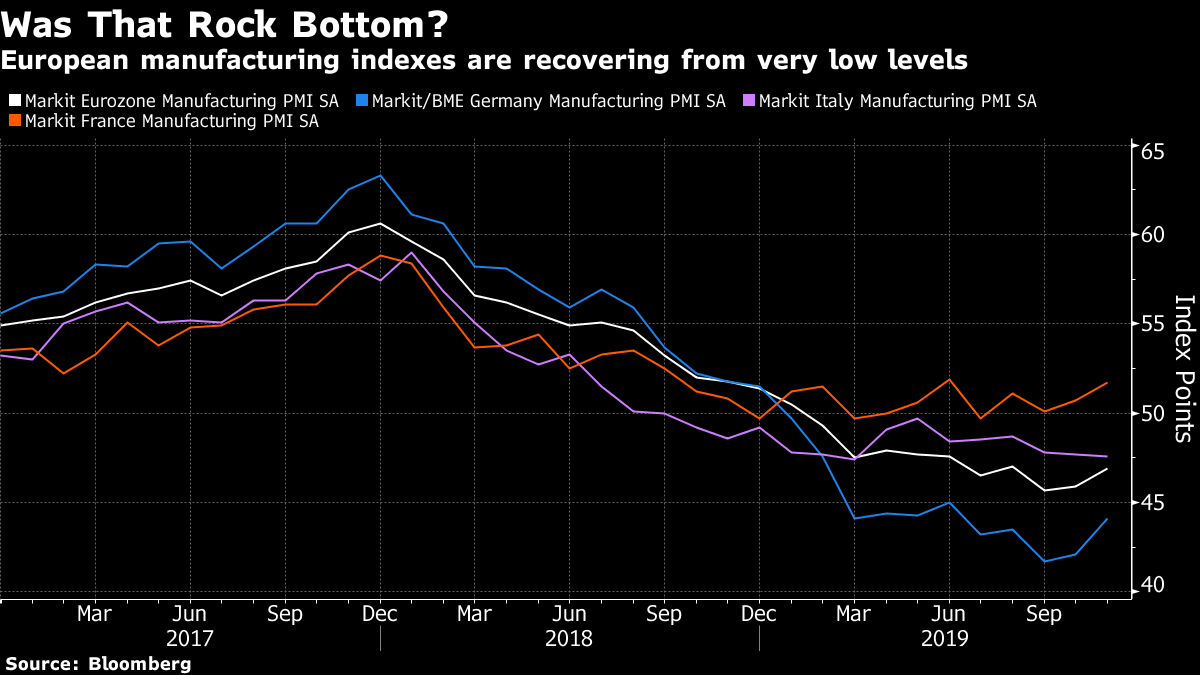

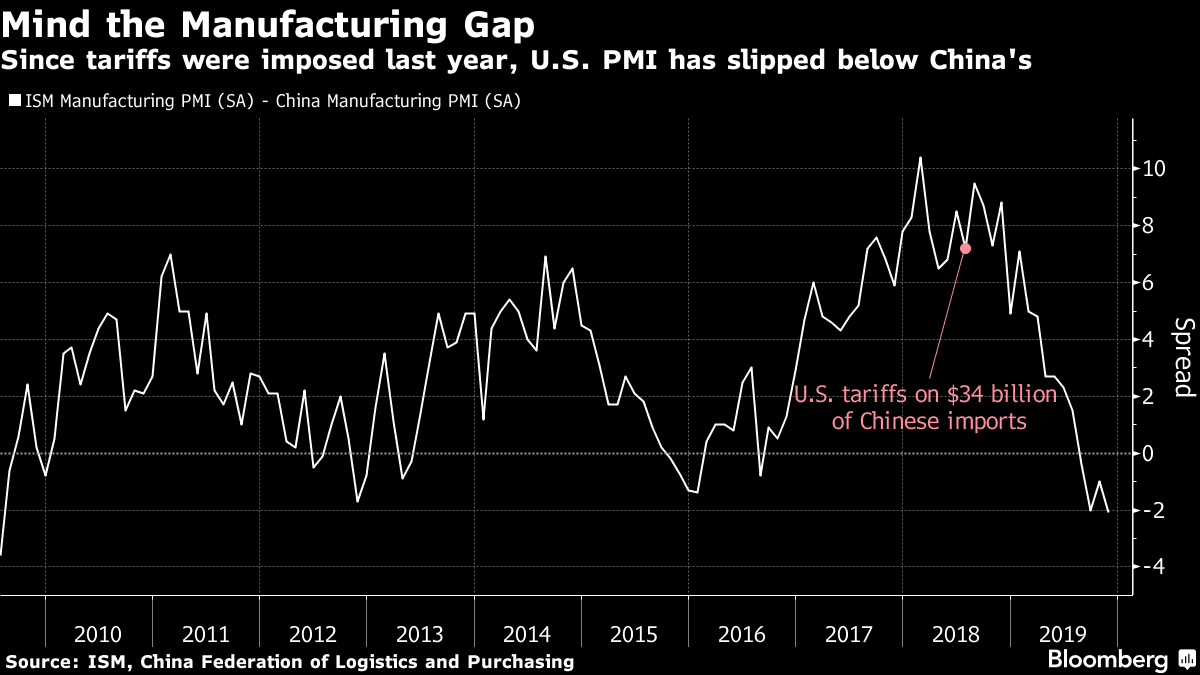

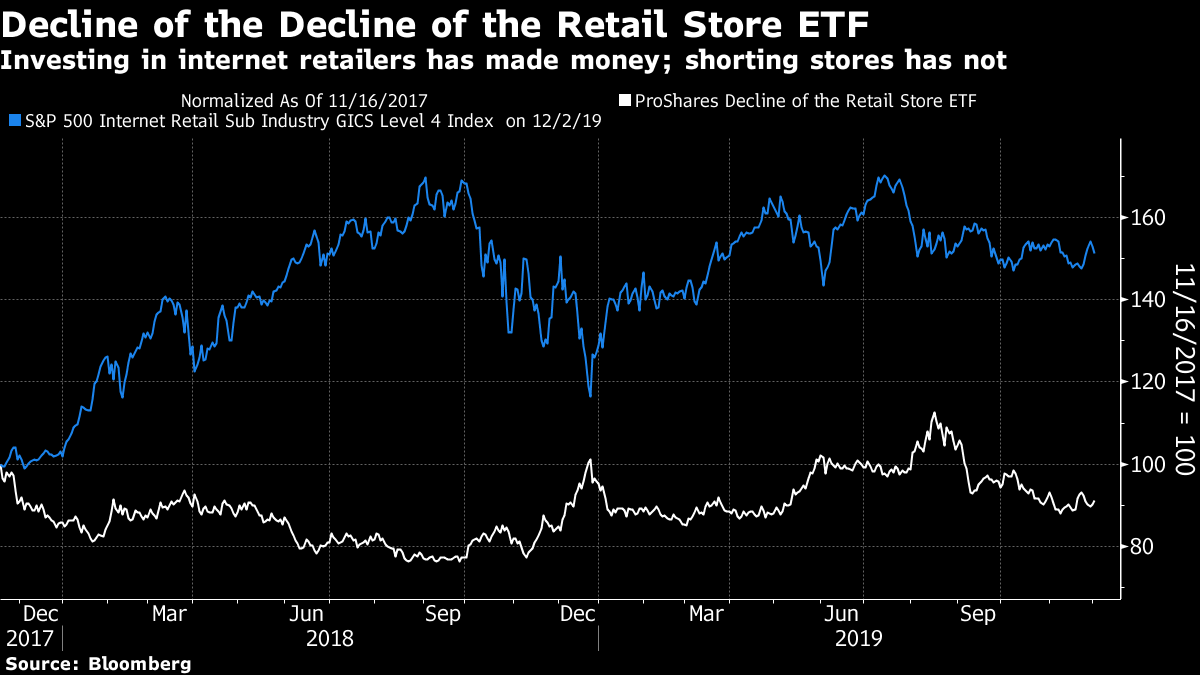

| What should we make of the world stock market's failure to set a new high just when it seemed within reach at last? To answer that, we might need to answer another question I asked in a column yesterday, about President Donald Trump's ludicrous announcement that he would levy tariffs on Argentine and Brazilian steel imports to retaliate against those countries' weak currencies. Did he do this to be "crazy like a fox," in accordance with some bigger strategic plan? Or because he didn't have a clue what he was talking about? I originally used Occam's Razor, and decided the likelier explanation lay in utter failure to understand the workings of currency markets and international trade. But it is just possible that Trump is being crazy like a fox. Either way, stock markets disliked the new tariffs, which spoiled the good cheer that had been spread by surprisingly good Chinese manufacturing data announced over the weekend. The dollar fell, and bond yields rose. Global stocks had one of their worst days in a while, dashing the chance for the MSCI All-World index to set its first record since the January 2018 high. The index reached within 0.12% of the landmark before slipping:  On top of the Chinese news, there was also relatively encouraging news from the eurozone. Germany is particularly reliant on the auto sector, and on exports, and this has made it the most obvious victim of the trade war to date. But the latest Markit purchasing manager indexes for eurozone manufacturing show a pattern of clear recovery from a very low base. (As is usual, the indexes are set so that 50 should be the border between expansion and contraction):  All of this was enough to help European stock markets open a tad higher, and should have been enough to bring world stocks to their record. Then came the presidential tariff-by-tweet, followed by some deeply disappointing U.S. manufacturing data. Thanks to the U.S. consumer, the American economy remains in good health, but the manufacturing sector looks more and more as though it is in recession. There are some idiosyncratic factors to explain this (the troubled aircraft-maker Boeing Co. being the greatest one), but the PMI is now at 48.1, and has been below 50 for four months in a row. So far, this manufacturing downturn is comparable to the one at the beginning of 2016, which also lasted four months and bottomed at 48. That one ended with Chinese stimulus and a recovery, without a recession. Will that happen this time? What's different now is that the manufacturing slowdown in the U.S. is worse than in China. For most of the last decade, the U.S. manufacturing PMI has been higher. It has now dropped 2 points below the Chinese equivalent, for its worst relative performance in a decade. Early last year, on the eve of the first tariffs, the U.S. was briefly 10 points ahead. On the face of it, the trade war has been a disaster for the U.S. manufacturers it was meant to help:  This brings us to the Trump tweets. As I argued in my column, it is absurd to complain that Argentina, a nation with inflation of more than 50% and a history of default crises, has a weak currency. The country would be only too happy to have a stronger peso, as this would aid the battle against inflation and ease fears of another default. Trump's tweet, at first glance, was plain stupid. But what if it was strategic? Trump badly wants an excuse to drop tariffs, which appear to be hurting U.S. manufacturers more than China's. He also badly needs a victory, with an election to come in a year. Increased tariffs on China are due to be imposed Dec. 15; can he find a way to cancel them? And if not, is there a way to limit the political damage at home? That leads to the notion that he is crazy like a fox. Argentina and Brazil aren't manipulating their currencies, but they are prime beneficiaries from China's hunt for new suppliers of agricultural products now that tariffs have been erected against the U.S. The tariffs may be a way to focus minds in China, and in the EU, on his preparedness to escalate if necessary. And by putting pressure on China's new key suppliers, he also puts pressure on China. Also, for domestic consumption, he gets his political base riled up about a new enemy. And this time, the enemy is nowhere near as powerful as China. A trade war with economies of South America really should be "easy to win" in his phrase. Finally, and most importantly, he continues to put pressure on the Federal Reserve. The Fed's U-turn this year has enabled the stock market to flourish. As Trump has turned the market into a referendum on his own performance, this helps him. Deliberately stirring up trouble ratchets up uncertainty and increases the chance that the Fed will feel obliged to ease policy again — thereby possibly delivering more months of strong stocks performance into the election. This strategy is much more likely to work if it is cloaked in the language of someone who doesn't understand the most basic principles of economics. So yes, it is very possible that Trump is being crazy like a fox. The only problem is that he is also being incredibly reckless. This chart shows how the industrial sectors of the S&P 500 and the mainland Chinese CSI-300 have fared since election day in 2016. Given that both are affected by the trade war, and operate in the same increasingly globalized economy, the divergence is extraordinary:  It looks very much to me as though the U.S. stock market is priced on the assumption that the next round of tariffs isn't going to happen. The Chinese market, still dominated by locals, is working on the opposite assumption. In this context, the fact that Trump feels the need to make high-stakes gambling ploys like opening up a new South American front looks alarming. There is a long way for the stock market to fall if some accommodation on trade cannot be thrashed out. But Trump really, really doesn't want the market to fall. If he is genuinely as crazy as a fox, he will find a way out of those tariffs. So let us hope that is the explanation. If I was right the first time, and he doesn't understand what he is talking about, we have problems. Finally, one last Thanksgiving footnote. This is the season for singing requiems for the bricks-and-mortar retailing industry. The weekend just gone featured photos of large and empty department stores. But even if the collapse of traditional retailing at the hands of internet retailers is a trend we can all see coming, it is hard to make money out of it. Two Thanksgivings ago, there was the birth of the exchange-traded fund with the cruel ticker symbol EMTY — the ProShares Decline of the Retail Store ETF. It took short positions in traditional retailers, and so offered a handy way for people to make money from the trend. The only snag is that, two years later, EMTY has lost a little money. Internet retailers have roared ahead, but stores have found ways to arrest their decline, at least for now:  Shorting has its uses, and the chances remain strong that EMTY will perform well in the long term. The business model of many large brick-and-mortar retailers continues to look doomed. But two years on we can see that even the strongest and most inevitable of trends can take a long time to work themselves out — and that the best way to take advantage of any trend is to identify the beneficiaries (internet retailers in this case) and invest in them. It's simpler that way, and it seems to work. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment