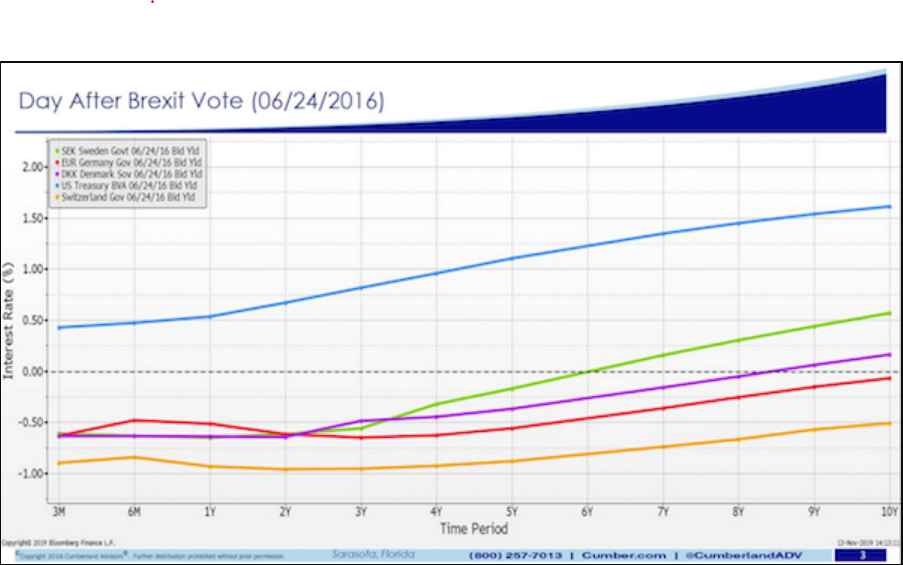

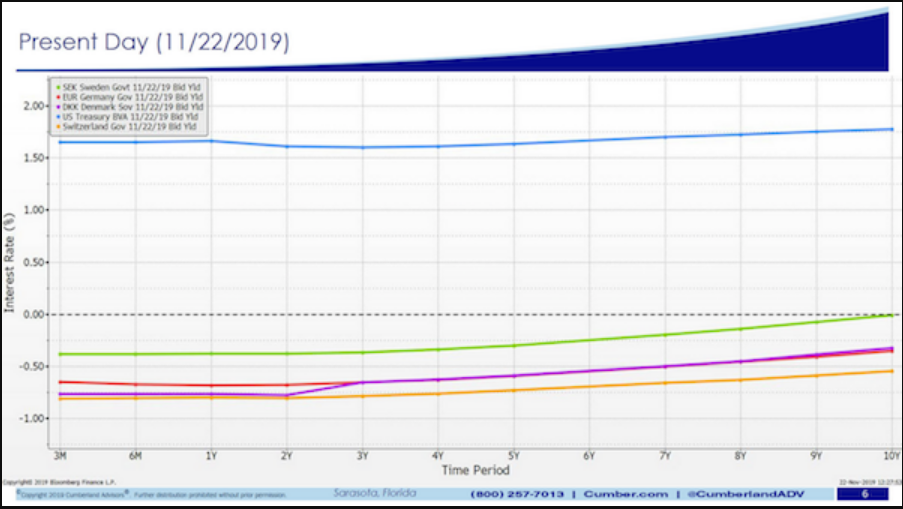

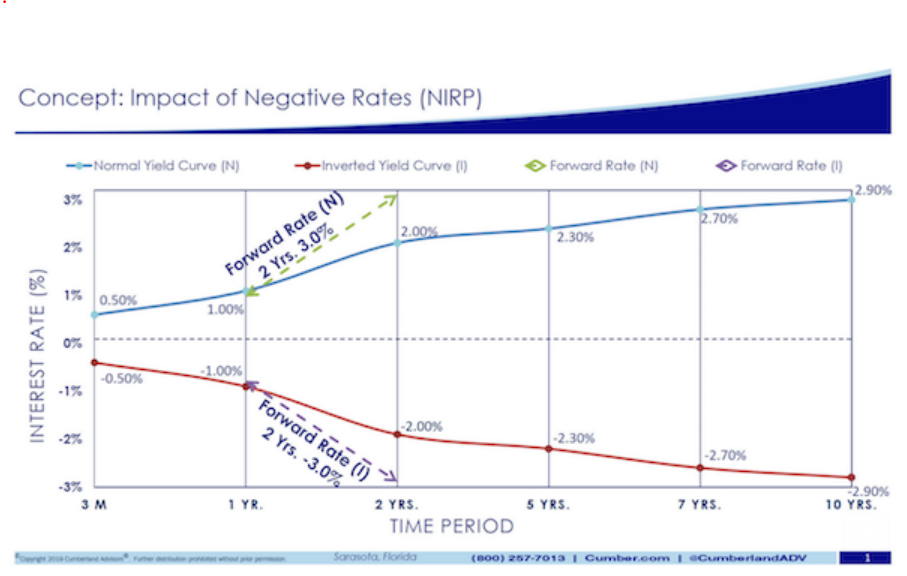

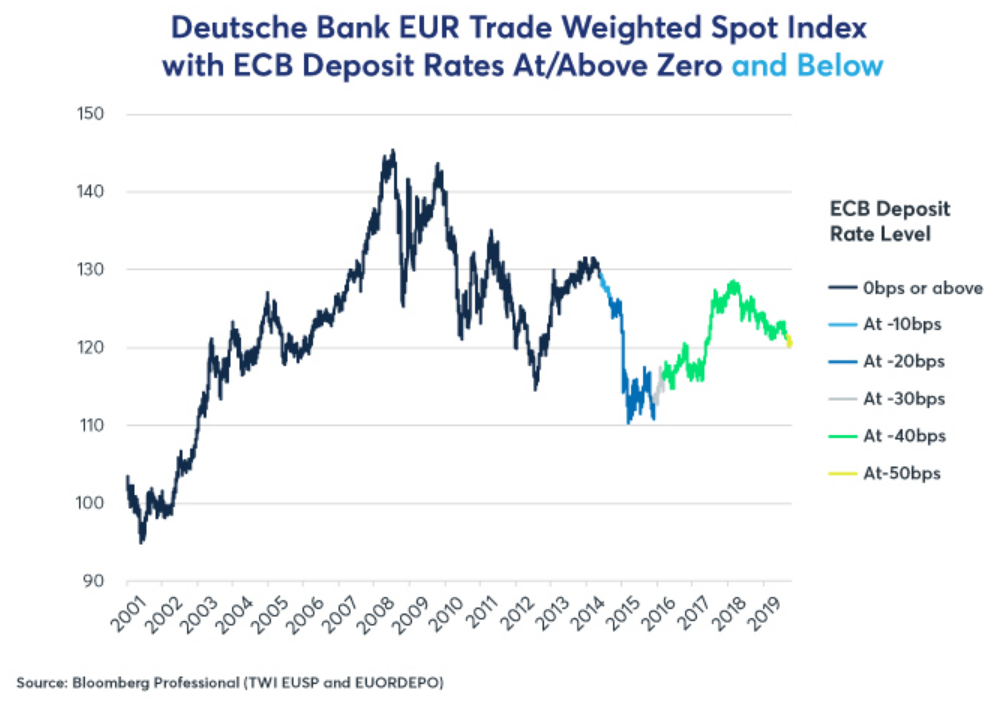

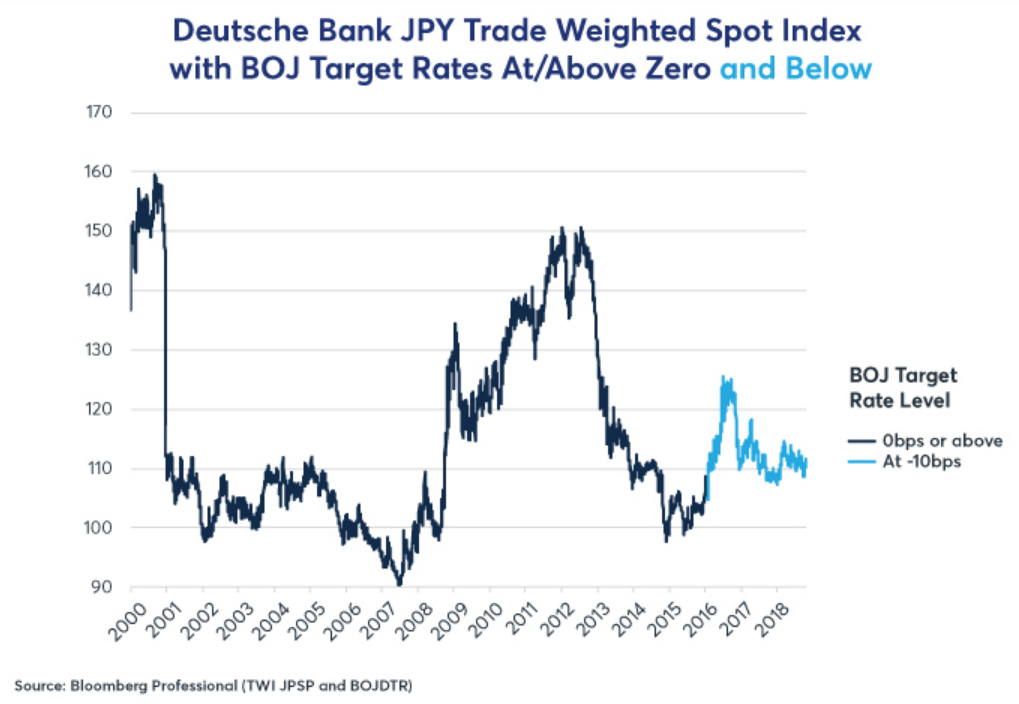

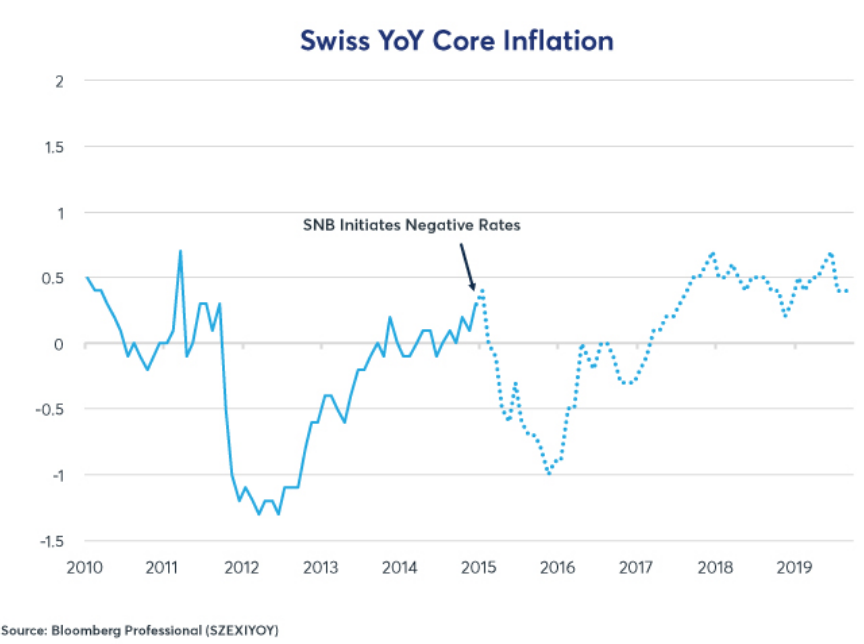

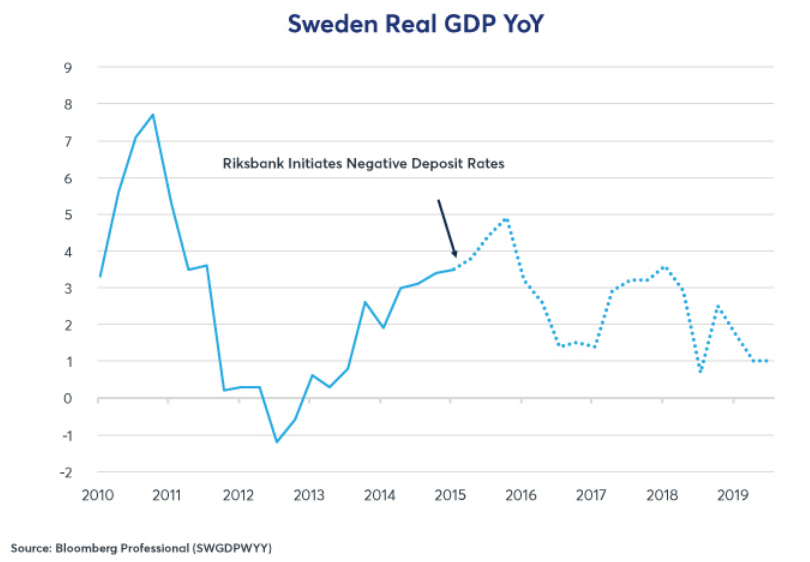

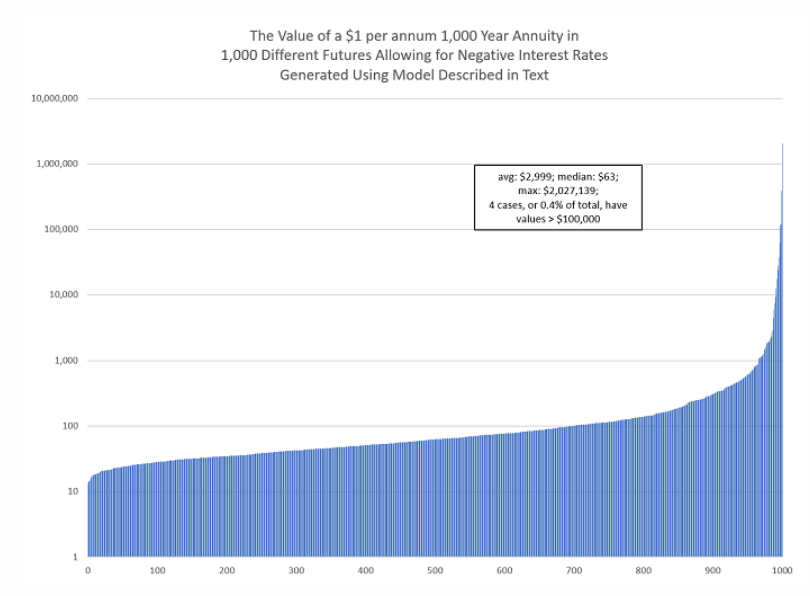

| What is so bad about negative interest rates? We know that President Donald Trump would like to see them in the U.S., and is angry with the Federal Reserve for not cutting rates below zero. Plenty of other central banks have of course done so. We also know that negative interest rate policy, or NIRP, makes many of us viscerally uncomfortable. Interest is supposed to be positive. We aren't supposed to pay people to look after our money. And plainly there is a rate below which rates cannot go. After a point, depositors would pull all their money from banks, and use a good solid safe filled with cash instead. Handily, the last week has brought some great and clear-cut work to show that NIRP could be deadly. Let me summarize it: Forward to the Future In a major paper to be published this week, David Kotok of Cumberland Advisors Inc. makes a devastating attack on the policy. The key insight concerns the effect on yield curves and future interest rates. Look at the yield curves for the NIRP countries compared with those for the U.S. in June 2016, when the shock of the Brexit referendum brought the 10-year Treasury yield down to what remains its recent low:  At this point, bond yields were shockingly depressed, but the NIRP economies still had clearly upward-sloping yield curves, and positive rates of interest over longer terms. Here is the latest update of this chart:  All the curves are far flatter, and the NIRP economies are settling at a lower level, roughly parallel with each other. Kotok goes through the mathematics of the forwards market to show that negative rates force the curve lower for years into the future. Currency forwards become ever more complicated because the forward market magnifies the difference between negative- and positive-rate currencies. Here is Kotok's stylized version:  If one country starts at +0.5%, and the other at -0.5%, the logic of the forwards market forces them to diverge over the longer term. That is what theory predicts, and history shows it is happening. Kotok's paper will soon be available on the Cumberland Advisors website. The basic point is that critical market signals no longer work, and that transaction costs increase: the notional pricing of the trillions of dollars and euros in swaps and derivatives is thrown into disarray. As a result, the banks and market agents sponsoring those derivatives must raise their pricing to protect themselves from this added risk induced by NIRP. When they raise their pricing, they add to transactional costs and therefore suppress economic activity at the margin. That is a reason NIRP slows growth and raises risk. Painful Nordic Experience Scandinavia has blazed a trail toward negativity, and it hasn't been a success. Finland, which Monty Python cruelly pointed out doesn't have a reputation as an exciting country, has been through the wringer. Mikko Mursula, head of Finland's Ilmarinen Mutual Pension Insurance Co. told Bloomberg that the impossibility of finding positive-yielding government bonds in the eurozone had driven funds into much more illiquid territory: The steps he's taken so far have led away from easy-to-sell assets, as liquidity becomes a luxury of a bygone age. It's a way to preserve returns, but also means the pension industry is delving into much murkier asset classes that might prove hard, or very time-consuming, to offload if markets turn. In some ways this is merely following the example of endowment managers. Yale's endowment long since showed the advantages of piling up on highly illiquid investments in private markets — this is where the market inefficiencies are, and endowments, with an infinite time horizon, can take on illiquid assets that others cannot. The problem is that pension funds have to disgorge far more cash over a shorter time horizon. For good reason, they have less appetite for risk, and for illiquidity. Not the gift that keeps giving CME Group Inc. earlier this month publisheda survey of the experience with NIRP in the jurisdictions in which it has so far been tried — Denmark, Sweden, Japan, the eurozone and Switzerland. It describes them as "not the gift that keeps giving." In terms of the core macroeconomic goals that central banks presumably had in mind when they cut rates below zero, the record is terrible. Negative rates might be expected to help weaken a currency. President Donald Trump plainly views the eurozone's negative rates as a weapon in a currency war. But while the euro weakened once rates hit zero, it has rallied as they have turned negative:  The same is true of the Japanese yen. The initial reaction to negative rates saw the yen weaken, but it is now about as strong against the dollar as it was when NIRP started:  Another obvious aim of NIRP would be to force inflation up. Making money so easily available certainly ought to lead consumers to bid up prices. This hasn't happened. Indeed, in the case of Switzerland, negative rates were followed by a collapse of core inflation well into negative territory. More than four years later, inflation isn't significantly higher than it was when the policy started:  Ultra-low interest rates might also be expected to spur economic growth. Again, this hasn't happened. In the case of Sweden, real GDP growth is noticeably lower now than when interest rates first dived below zero:  We can never know the counterfactuals, of course. In all these examples (and the CME cites many more) it is quite possible that outcomes might have been even worse if central banks hadn't resorted to negative rates. But with negative rates now an established fact of life in much of northern Europe, the fact remains that there is no clear example of a successfully applied NIRP. This isn't like Keynesian spending splurges or big tax cuts, which can have big short-term impacts; there is simply no evidence yet of NIRP having a positive effect at all. From Negativity to Infinity and Beyond In this piece, the brilliant Victor Haghani of Elm Partners Management LLC in London wrestles with some of the impossibilities of negative rates. The problem is that they send some mathematics into hyperspace. Critically, a perpetuity (a bond that pays forever without ever being repaid) can be valued by dividing its coupon by its yield. If that yield is negative, the value of the bond becomes infinite. Rather than bothering with infinity, Haghani then tried looking at a 1,000-year bond, which has many of the same characteristics as a perpetuity. Introducing negative rates as a possibility rendered the exercise of valuing such a bond absurd. In the following example, Hagani looks at the range of possible values for a bond paying $1 per year for 1,000 years, with probabilities based on the current rates for German bonds with maturities of one, five, 10 and 30 years. A few enormous values skew everything:  My colleague Brandon Kochkodin explored Haghani's ideas here, and you can watch the man himself being interrogated on Bloomberg TV here. The mathematics is difficult so it is worth reading and re-reading Haghani's original piece. And if you feel awkward that you have never conducted the thought experiments that Haghani is trying, don't be. As he points out: "Marshall, Fisher, von Mises, Hicks, Hayek, Knight, Keynes and Friedman, all wrote books and articles proposing differing theories of interest rates. One common thread was that none of them envisioned negative interest rates as a realistic phenomenon they needed to explain." If a roll call of the greatest economists ever to have lived, on all sides of the ideological spectrum, never thought through what would happen if rates went negative, we needn't feel too bad about omitting it ourselves. It also tends to suggest that NIRP isn't a terribly good idea. The NIRP Nerds Have It There is a bottom line to all of this. The mathematics are counterintuitive, but those prepared to do the calculations have shown clearly what we might have expected in the first place. Once rates go negative, it grows harder and harder for financial markets, and hence modern economies, to operate. Whatever the U.S. president might want, we should expect in the next few years to witness a difficult and hazardous retreat from NIRP. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment