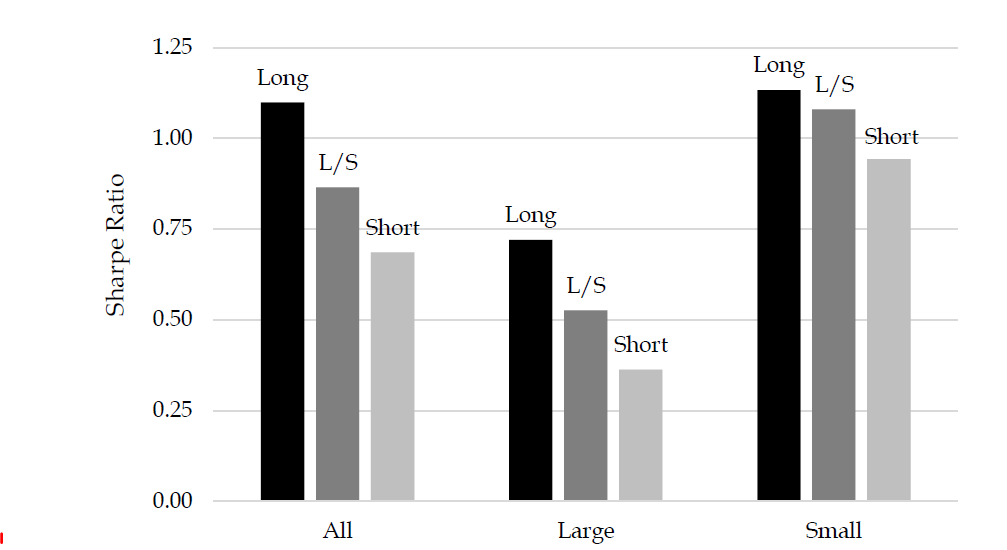

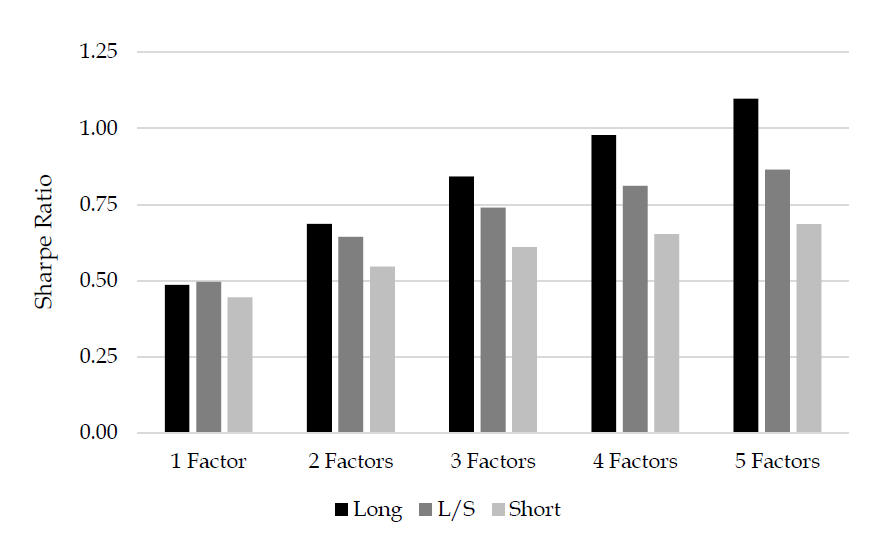

Gentlemen, Drop Your Shorts Quant investing, and indeed much of the hedge fund industry, is built on the power and freedom that come with the ability to sell short. When you short a security (borrow and then sell it, meaning you make money if the price falls and you then re-buy it), you can profit when markets go down as well as up. Hedge funds, unlike mainstream mutual funds, can sell short, and this opens exciting new strategies. In 2000 and 2001, as the dot-com bubble was bursting, equity hedge funds succeeded in making money, and many investors noticed. "Liquid alts" — hedge fund-like strategies on offer to retail investors — tend to be based on this, as is much of the emerging work in "smart beta" — tweaking well-known indexes to emphasize particular factors. Academic finance is also implicitly based on the power of shorting. The investment factors identified in the academic literature are usually expressed on a "long-short" basis. For example, the value factor (buying stocks which look cheap compared to their fundamentals) is expressed as the gap between the performance of the cheapest (long) and the most expensive (short). The same is true of momentum strategies (long stocks that have been winning, short stocks that have been losing), and low-volatility (long low-volatile stocks and short more variable ones), and so on. The factors laid out in the massive empirical work by Eugene Fama of the University of Chicago and Kenneth French of Dartmouth College are expressed on a long-short basis, and so the rest of the academic community tends to follow. Now comes an academic wrecking ball, from David Blitz, Guido Baltussen and Pim Van Vliet, a group of quants who work for the Netherlands-based fund manager Robeco. In this new paper, called "When Equity Factors Drop Their Shorts," the Robeco team breaks down the contribution to performance made by the long and short legs of equity positions — and finds that the short position is scarcely worth the bother. The article is published today, and is about to go through the academic wringer (as have other pieces by the Robeco team). For now, I will outline the main findings. Very many people have an incentive to prove them wrong, so we can expect a robust academic and professional debate over this. Arguably the central finding is contained in this chart. The researchers looked at returns on U.S. stocks from 1963 to 2018 which have already been closely researched. After testing a long strategy, a short strategy (merely betting against the worst stocks according to a factor), and a long-short strategy, risk-adjusted returns turned out better in all cases for the long-only strategy. As might be expected, though, returns were higher and the gap between the long and the short end of the trade was narrowest, in small-cap stocks, where we can assume there is less information and the markets are less efficient:  To be clear about what is being measured here, the "long" is compared to a straight long position on an index, while the "short" position is compared to a short position on the relevant benchmark. Markets tend to go up over time, so the long will naturally tend to do better, but that isn't what is being measured here. Instead, we see that the "long" side of a factor (that it is very cheap, and so on) is a better predictor of outlying performance than the "short" side of that factor. Extremely expensive stocks aren't as likely to lag the market as extremely cheap stocks are to lead it. Also, the research stands up that there are diversification benefits from adding extra factors. All the strategies improve their risk-adjusted returns this way; and the advantage of the "long" over the "short" widens with extra factors.  One other important finding is that while the long sides of different factors tend not to correlate with each other, the short sides do. Put more in layman's language, there are a number of different ways to spot a stock with a good chance to outperform, but stocks with a good chance to underperform look bad according to a number of different factors. Expensive stocks ("short value") also tend to be volatile ("short low-volatility"), and so on. This again suggests that there is little point in using factors to identify individual stocks to short. All of this research is on the basis of "zero friction." In other words, it assumes that it is as cheap to maintain a short position as it is to maintain a long one. In real life, this isn't true. Selling short requires paying interest to someone, and that interest will increase if the stock is a popular one among short-sellers. There is a risk that the lender will demand their stock back. And shorting requires a thick skin. Companies seldom complain about investors buying their stocks, but tend to get very vocal about being shorted. Finally, there is a risk-reward issue. The returns on a short position are capped at 100% (if the stock goes to zero), while the potential losses are infinite. So the balance is set against shorting even before starting. None of this excludes forensic short-selling by specialists. Selling short isn't just the opposite of choosing stocks to buy; to short a company with confidence requires a close examination of its books and its business confidence, and a conviction that it is fatally wounded. To be sure the strategy works, short-sellers need to be prepared to talk about their ideas a lot in public, and take a lot of flak. Some famous successes show that short-selling like this is a vital part of the market eco-system — think of Jim Chanos's attack on Enron, Bill Ackman's attack on the monoline credit insurers before 2008, or David Einhorn's attack on Lehman Brothers. But this research shows that using factors to identify short candidates the same way that we identify stocks to buy isn't a good way to deploy capital. For those who don't want to expose themselves to the overall direction of the market, it is far cheaper and easier, and no less effective, just to take a short position in the index. All of this implies that a lot of hedge funds and quants are wasting their time and money, so we can expect this paper to face a robust response. But the outline of the argument looks clear and persuasive. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment