Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that wishes they did as many reps of lifting the bar as Fed Chair Jerome Powell did this week. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter

Powell Deadlifts

A Fed chair walks into a bar. He raises it – in both directions.

That's both a poor, niche dad-joke straight out of Alice in Wonderland and also the story of the Federal Reserve's third consecutive interest-rate reduction delivered by Chairman Jerome Powell.

The language in the central bank's statement Wednesday was left almost entirely unchanged, except for the removal of the willingness to "act as appropriate" to sustain the expansion. Back in June, the introduction of this language was proof that the Fed would indeed act, rather than be "patient," and teed up the subsequent cuts. During the press conference, Powell indicated that monetary policy is in a "good place" right now, and is "likely to remain appropriate." It would require a "material reassessment of our outlook" to boost accommodation, he added, while risks like trade and Brexit had also subsided since the September meeting.

The Fed is now putting forward the view that acting as appropriate means not acting at all. It's the kind of retort that a kid – like the one I was – might use when his parents suggest his bedroom needs tidying. But markets are taking the line better than parents might. Although two-year Treasury yields spiked on the heels of Powell's remarks, they soon calmed down. That's because he also indicated that the bar for hikes is even higher.

"We would need to see a really significant move up in inflation that's persistent before we would even consider raising rates," he said.

This is more important than you might have thought. The time at which the Fed would resume hiking rates had been pulled forward since the September meeting. Powell effectively crushed those expectations.

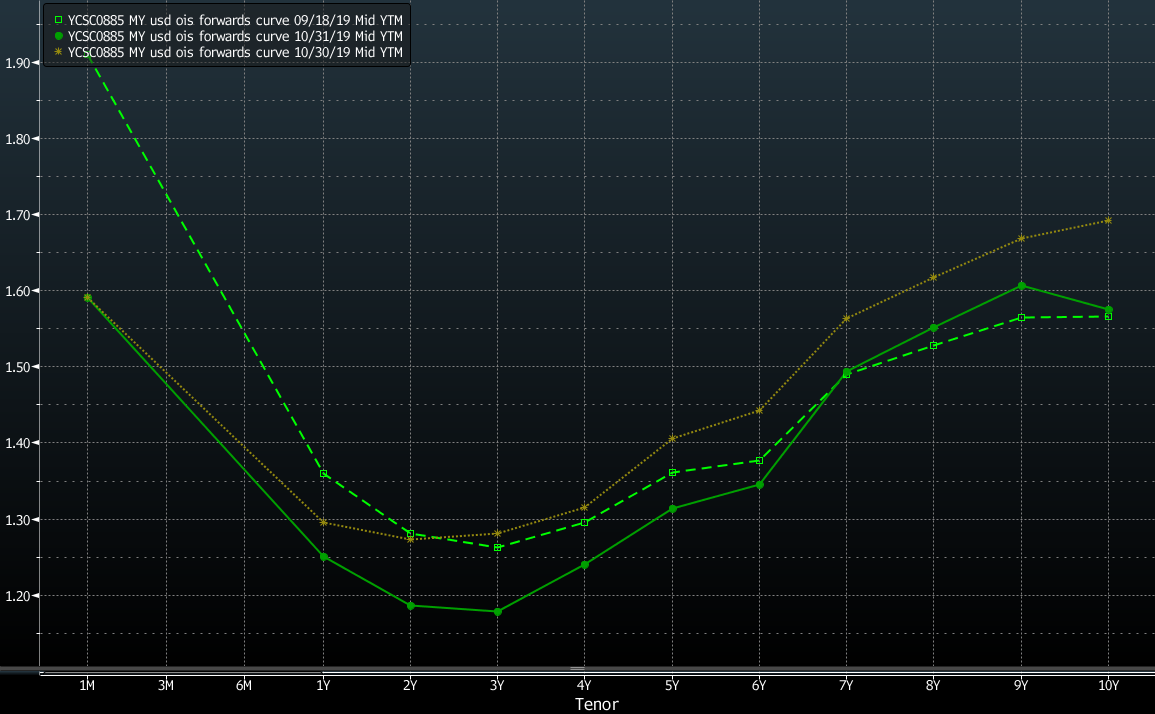

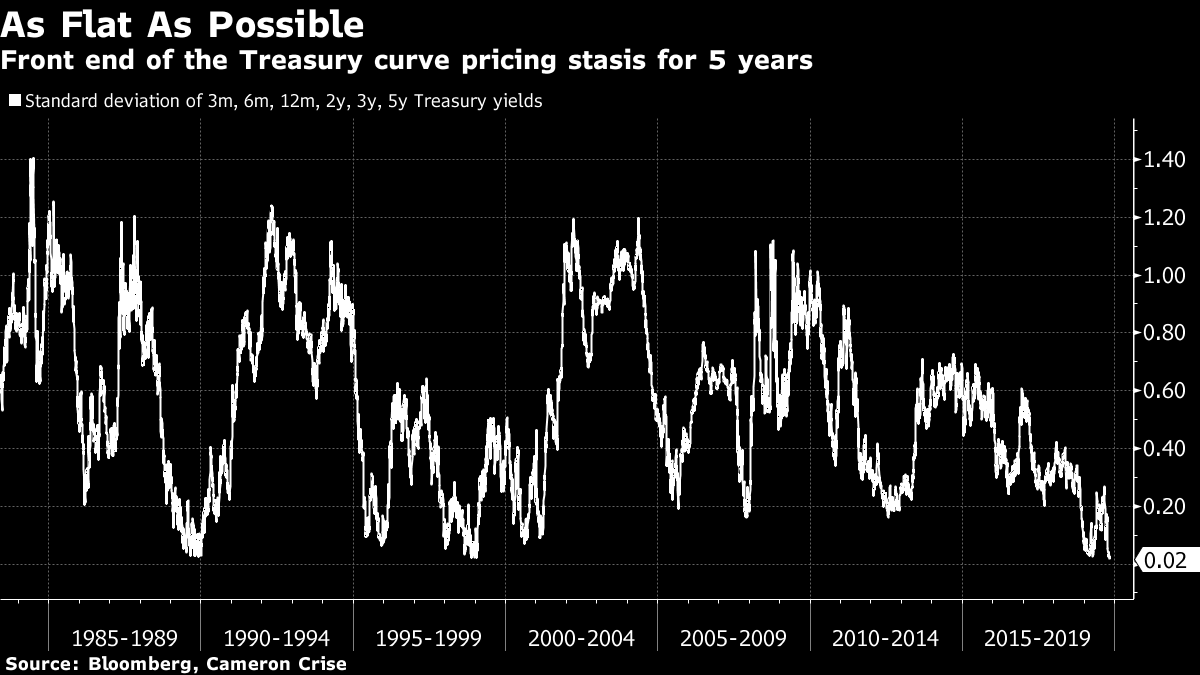

The ensuing result is that the dispersion in Treasury yields from three months to five years is at its lowest level on record. A flat curve is pretty much a feather in Powell's cap, even if there's little chance rates will be on hold this extent.

Powell's desire to move the Fed to the sidelines raises the question: just how long could any pause be? If history is a guide, the longest Fed pause in the past 30 years (excluding its time at the zero lower bound), was from March 1997 to September 1998. However, within the ZIRP period, one could argue that there was a longer stretch, from October 2013 until lift-off in December 2015, when policy – including balance sheet policy – was static.

To be sure, the market pricing, on its face, indicates some doubts as to whether any pause will be lengthy. In the event that traders really believed the Fed was on hold for a long time, you might expect to see the spread between January 2020 and 2021 fed funds futures compress significantly. Alas, it's actually widened since the Fed meeting, though Thursday's risk-off session on trade concerns bears some of the blame.

Morgan Stanley's Matthew Hornbach helps reconcile this seeming dichotomy.

"This guidance cuts both ways with respect to further rate cuts: 1) it means the bar is high for the Fed to cut rates again, however 2) a "material" change in the outlook may lead to a "material" reduction in the target range for the fed funds rate. This suggests that the net rate cut, should it come, could more easily be a 50bp rate cut instead of a 25bp cut. This idea should serve to keep a healthy negative term premium in the pricing of Fed policy for 2020."

Stocks Don't Care About Bonds (As Much)

The equity market's resilience this week amid the twists and turns of the Treasury market was a sight to behold.

The idea that the Fed was done on delivering easing didn't really rattle stocks much. Think back to the start of the year, when the risk rally hadn't been so reliant on lower real rates since 2012. We're clearly in a new market regime.

Such an outcome might have been expected, based on how the market's been operating in a "good news is good news" paradigm during at least the second half of this year, but it was nonetheless impressive.

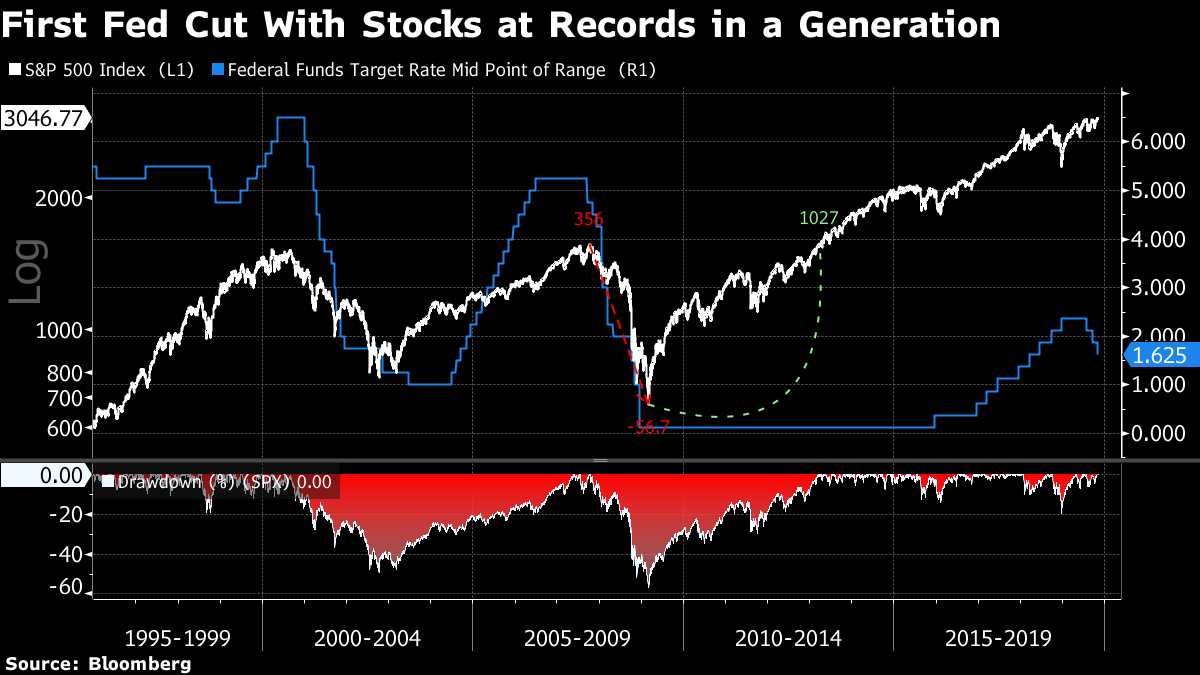

For most of the first half of 2019 – and even after the first rate cut, when the notion of a mid-cycle adjustment roiled stocks – the equity market was signaling that it needed the Fed's help. Now, traders are suggesting they only need the Fed to do no harm. The S&P 500 Index closed at an all-time high on a day when the Fed cut rates for the first time since January 31, 1996.

Ultimately, when central bankers say they'll only hike on a material pick-up in inflation and such an increase is not on the horizon, that's a pretty big endorsement of risk-parity oriented portfolios.

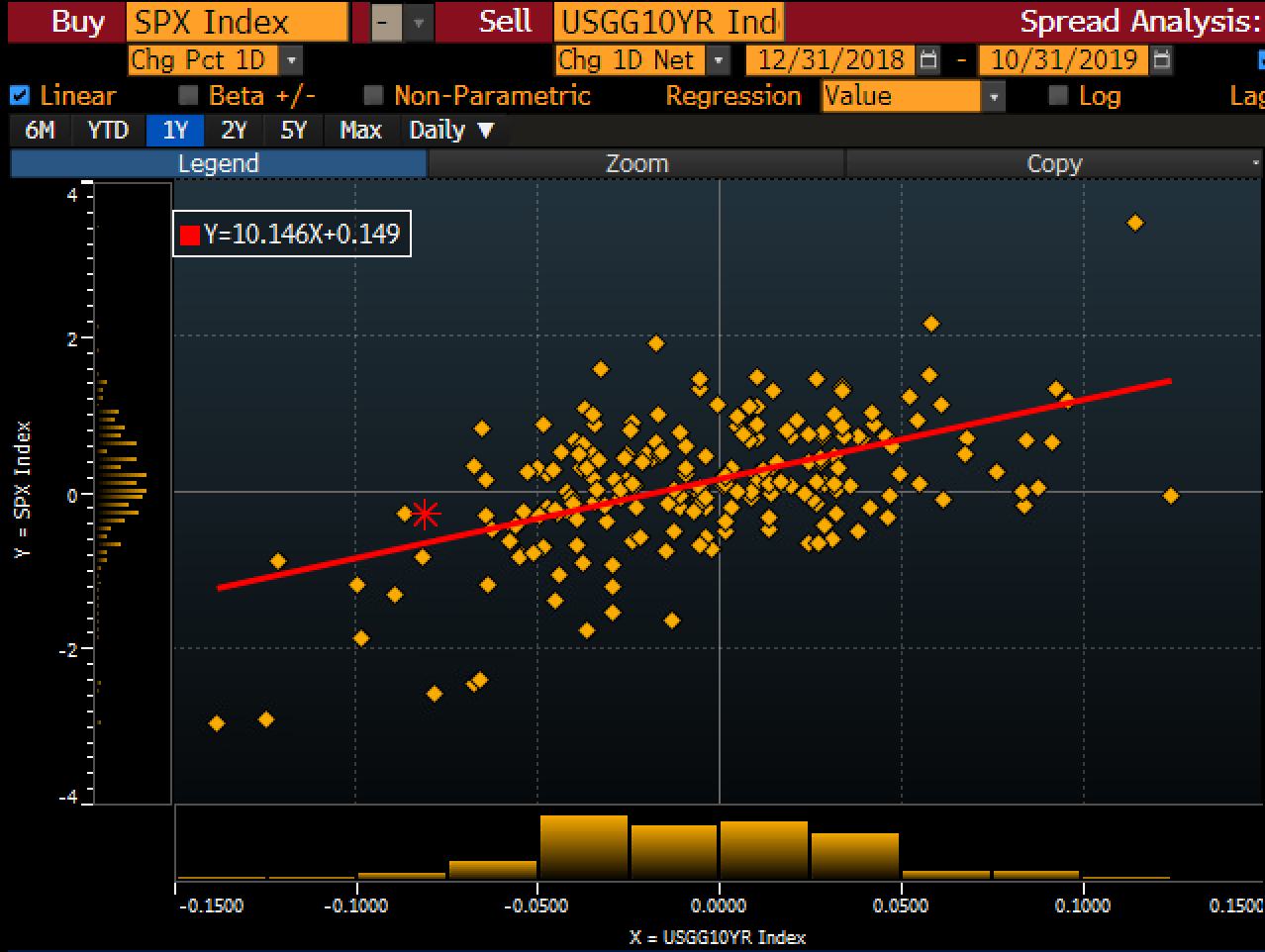

The equity market's newfound relative ambivalence to the Treasury market continued on Thursday. Ten-year Treasury yields tumbled about 8 basis points amid a rash of underwhelming data and reports that a comprehensive U.S.-China trade deal wasn't nearly as likely as the barebones so-called phase one deal. The benchmark borrowing cost dipped below 1.68% – nearly 20 basis points off its highs of the week.

And yet, the S&P 500 Index only fell 0.3% on the day. That's tied for the smallest loss of the year for a session in which the 10-year yield posted a decline of that magnitude. U.S. stocks have dropped 1.4%, on average, during such a furious rally in rates in 2019.

Post a Comment