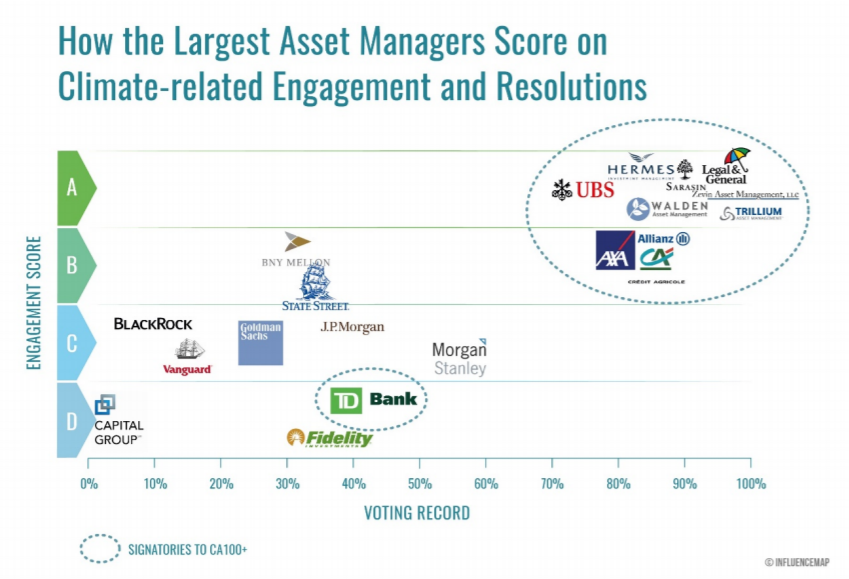

| If you want to see the future of climate-based investing, you need to look at Harvard and Yale. For those tired of debates dominated by elite universities, note that I am not talking about what goes on inside those hallowed halls. I am referring to last weekend's football contest between the two Ivies, known as "The Game." This edition of the ancient rivalry was certainly exciting (Yale came from behind to win 50-43 in double-overtime), but all attention was stolen by events at halftime. Students from the two universities' campaigns to divest from fossil fuels (Yale Endowment Justice Coalition and Divest Harvard), staged a joint invasion of the field. Both want their endowments (the two largest university nest eggs on the planet) to get rid of all exposure to oil, coal and gas. They also called for divesting from holdings in Puerto Rican debt. This is important because university divestment campaigns have a history of working. In the 1980s, when the apartheid regime in South Africa was the target, such campaigns contributed to the pressure on the country that eventually led to the release of Nelson Mandela and black majority rule. Universities tend to be averse to negative publicity, while trustees of their endowments tend to prefer the quiet life. The incident also casts light on a new report, Asset Managers and Climate Change, by the London-based climate-change think tank InfluenceMap. Their analysis found that the world's 15 largest investment institutions, which have $37 trillion in assets under management between them, are collectively deviating from the "Paris-aligned" allocations needed to reach the Paris Agreement goal of stopping global temperatures rising by 2 degrees. Doing this primarily requires divestment from automakers, while making big investments in alternative energy producers. World markets as a whole deviate by 18%; the big institutions deviate by 15% to 21%. This has little to do with choices made by the institutions themselves. With passive funds increasingly dominating all others, many of the biggest fund managers offer big exposures to carbon-emitters simply because of their weight in the index. The institutions are merely passively (in several senses of the word) doing what their clients ask them to do. At this level, passive investing can be seen as an obstacle. The growth in Wall Street's offering of investments based on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles can be seen as a way to fight back, as it justifies the existence of active managers. The problem with this is that index providers have already provided ESG benchmarks that can minimize carbon exposures without the need for active portfolio management. They can also do some financial engineering to make sure that your investment performance doesn't suffer as a result. This chart compares the performance of two exchange-traded funds. One is based on MSCI's all-country ACWI index, while the other is in a low-carbon version of the same index, which claims to reduce the carbon emissions of the portfolio by 77%. Spot the difference:  Now, compare the market cap of these two ETFs whose performance is virtually identical. The ACWI index holds $11 billion. The low-carbon version, almost five years after its launch, has just $450 million. So any overweighting of high carbon-emitters isn't really the fault either of asset managers or of index providers, but of the ultimate clients. That is why the behavior of the young Harvard and Yale activists at halftime last weekend might matter; as the South African divestment campaign shows, it only takes a little activism to move a lot of money, and thereby change the behavior of some powerful people. Fund managers can be active in more ways than selecting stocks. They also have a key role as stewards, voting their shares and putting pressure on managements. The leading passive managers, such as BlackRock Inc., have adamantly defended their record on engagement in recent years. As they do not have the ability to sell their stocks, the argument goes, they have no choice but to be active. However, the InfluenceMap research suggests that the big U.S. passive providers are also passive in their dealings with company managements. It is left to smaller active fund managers, and to large passive houses such as Legal & General in Europe — where pressure on them to be active environmental students is intense — to put pressure on managements. In this chart, a higher voting record means higher support for resolutions on climate-related issues:  The key difference here is evidently geography. In Europe, climate change is now widely viewed as an emergency, and asset managers have little choice but to act as the public's agents and put pressure on companies. In the U.S., where a large chunk of the population thinks climate change is a hoax, the dynamics are very different. There is no reason why large passively run funds cannot make environmentally friendly investment decisions, and agitate boards as environmentally friendly stewards. The reason they aren't doing this in the U.S. is the lack of pressure from the public and clients. Should American opinion swing on this issue, we can expect sharp moves out of carbon-emitting companies, and much more pressure on industry in an environmentalist direction. What matters is whether the public as a whole is prepared disrupt the game the same way the Harvard and Yale students did. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment