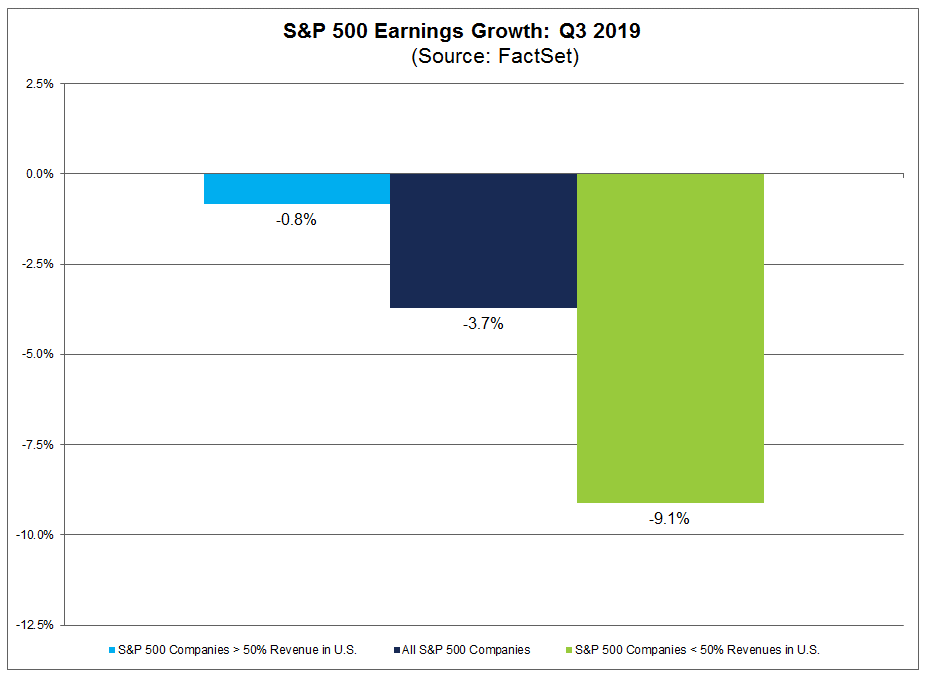

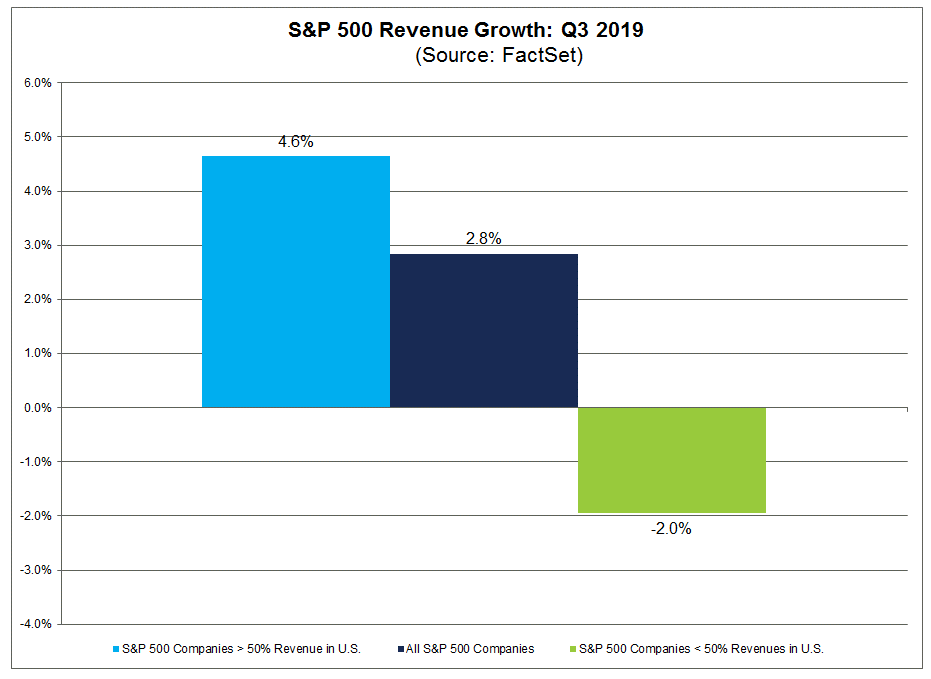

The Open Veins of Latin America In a classic of Latin American literature, the Uruguayan leftist Eduardo Galeano referred to the "Open Veins of Latin America" . His subtitle was "Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent," and he meant that the rest of the world was permanently bleeding the continent and robbing it of its natural resources. It is brilliantly written, but espouses a philosophy with which most of the world's investors are probably in deep disagreement. Which makes it somewhat ironic that they tend to value the continent's stock markets as though Galeano's analysis was exactly right, and the whole region could be treated as one gigantic mine:  MSCI's Latin American index has underperformed the rest of the world ever since the commodity cycle started to turn negative at the beginning of this decade. Previously, its rise mirrored that of industrial metals as China's economic growth entered its heyday. A look at how the continent has performed compared to emerging Asia — a region with very limited natural resources by comparison, but a far more dynamic private sector — again shows the importance of the commodity cycle. It also shows that views of one monolithic "emerging markets" complex are over-simplified.  As is now evident, Latin America has been trapped in a bear market for a long time, in large part because of over-simplistic views of the region. This isn't great for Latin America, but does at least help to explain recent market events. October has been a torrid month. Beyond the public disorder in Chile, there have also been similar protests in Ecuador, while there is a disputed election in Bolivia, and another close election is going to a second round in Uruguay, while Argentina has voted a Peronist back into power after only a four-year interregnum. The market hated the populist policies of Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner when she was president; now she's back as vice president. Added to all of this, the Mexican city of Culiacan was turned into a virtual war zone after the authorities arrested the son of a narcotics kingpin. His henchmen forced his release. Added to all of this, the region suffers from the uncertainty over U-S.-Chinese trade, while Mexico is dependent on a successful passage for the USMCA trade agreement. This is a chapter of disasters of the kind that Galeano reels off in his book. And yet October has been a good month for Latin American equities. They have performed comfortably better than the rest of the world:  Why? Primarily because of Brazil, which accounts for more than 60% of the MSCI index (while Argentina and Chile, the two troubled countries of the southern cone, account for less than 10% between them). With much of the international money in the region now flowing through passive or benchmarked funds, strength for Brazil tends to translate into flows for the other countries in the region as well, despite their problems. Virtually ever since the credit crisis, foreign investors' perception of Brazil has been dominated by pensions. Its existing plan was seen as dangerously over-generous and fragmented, and posing a grave risk to the country's credit. Jair Bolsonaro, the country's right-wing populist president who was elected last year, showed little serious interest in the issue during the campaign — but has now succeeded in bashing heads together to get a deal that should save Brazil some $200 billion over the next decade. There is much more to be done — it is good that Brazil can avoid bankruptcy, but it really needs to grow. The symbolic value of getting a deal is immense, however, as far as investors are concerned. With its passage, they moved the spread of Brazilian over U.S. bond yields to below even its pre-crisis level:  Significantly, Brazilian debt is now seen by markets as less risky than Mexican equivalents. Mexico also has problems with violence, poverty and weak growth, of course, but for the last quarter-century it has had a far more conservative fiscal policy than Brazil, and has been rewarded for that by the credit markets and rating agencies alike. Until now:  Mexico's relatively stable credit spread shows that its own new president, the left-populist Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, know as AMLO, has managed to avoid antagonizing investors who were wary of him when he arrived. But the performance of Brazilian debt is extraordinary. All of the three main rating agencies still rate Mexico's debt as several notches safer than Brazil's — and it will now be very interesting to see whether they follow the market. Where does the region head next? Investors enthusiastically buying Brazil might bear in mind that a chief grievance of the protesters in Chile was that country's pension system, on which pension reforms in Brazil were modeled. Chile's president had to promise improvements to pensions just as Bolsonaro was getting agreement to slash entitlements. As Brazil has a tradition of taking to the streets it will be interesting to see whether his breakthrough deal gains public acceptance. The issues that angered Galeano have also not gone away. Inequality in Chile, a highly stratified society, has actually reduced somewhat over the last few decades, while the economy has grown. But it remains the most unequal country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, in a virtual tie with Mexico. At a certain point, slow growth coupled with a perception of injustice became intolerable. And the most critical issue is also much as Galeano saw it. The region remains hostage to the whims of foreign great powers, although now it is China, rather than North America or Europe, that matters most. A durable new U.S.-China trade relationship, and a return to stronger growth in China, would make life far easier for the entire region. Will it happen? Globalization, Schmobalization The S&P 500 hit a new all-time record Monday, on the back of good earnings. There is much to say about this, but one point that needs to be made is that those earnings were largely "Made in the U.S.A." Not all companies break out their profits and revenues by country, so this is difficult to track, but FactSet has made a heroic attempt. This shows mediocre profit figures for domestically focused companies, and terrible results for those who derive more than half of their profits from outside the U.S.:  This is largely because of revenues (which in turn are not flattered by a strong dollar). Domestic companies managed to increase their sales compared to a year earlier, while those most thoroughly based outside the U.S. suffered a fall:  Since the worst days of 2008, the S&P 500 has outperformed the rest of the world's stocks by some 150%. A big part of that is that American companies have a more vibrant home market in which to do business. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment