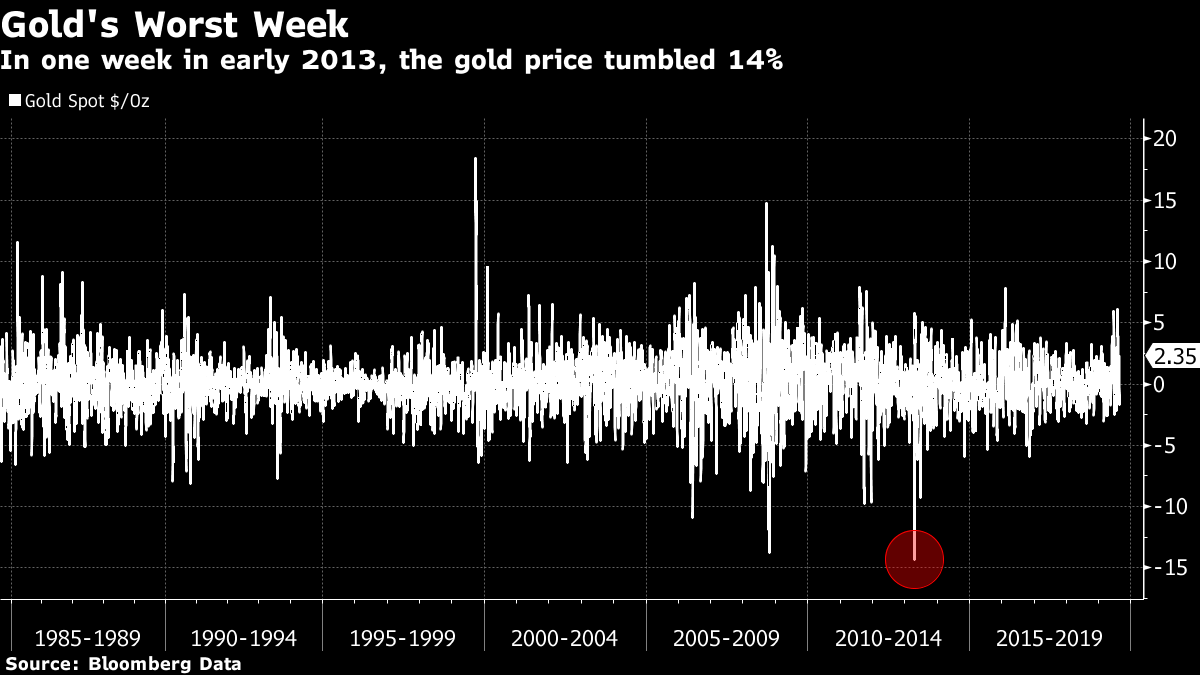

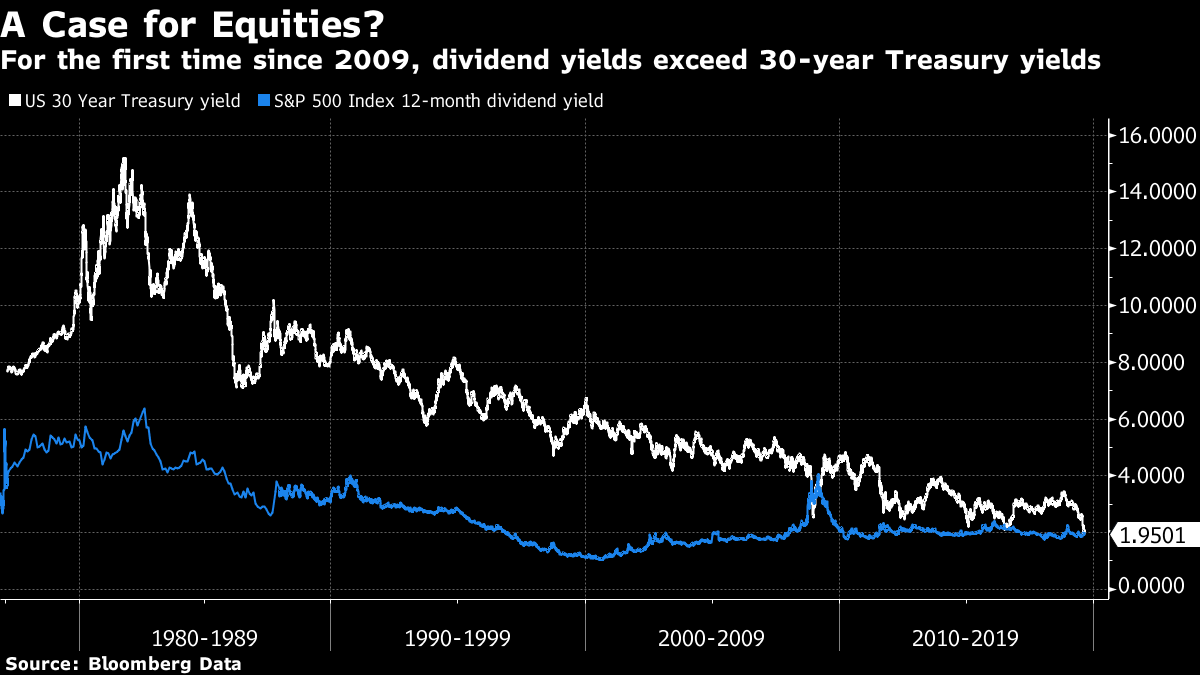

| The decade since the financial crisis feels like one long drawn-out, asset purchase-fueled rally, but it has had some turning points. Of these, the excitement of 2013 does not get the attention it deserves. And gold was at the heart of the action. By the spring of 2013, it was growing apparent that ultra-easy monetary policy had not, as widely and reasonably feared, sparked faster inflation. The Fed seemed ready to start to normalize policy, easing off quantitative easing asset purchases and then maybe even raising interest rates. So it was that gold suddenly had its worst week in more than three decades. This chart shows weekly moves in the price of gold in dollar terms.  Hot on the heels of that almighty shock in the gold market came the so-called Taper Tantrum, as a few words from then-Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke about the possibility of steadily reducing asset purchases at some time in the future led to a sharp increase in bond yields around the world. In a few weeks, and with a few almighty bumps, global markets appeared to accept that higher rates of inflation was not fated, and that a more normalized interest-rate policy was on the way. The dramatic moves of the last few days have, in aggregate, signaled the belated moment when the market at last rethinks this judgment. Gold is one good day's trading away from regaining its level at the beginning of its fateful week at the beginning of April 2013. The bear market in the precious metal has given way yet again to a belief that it is worth holding.  This has happened even though there is no sense that inflation is coming back. Gold is traditionally seen as a haven from faster inflation, but it is also seen as a haven from feckless central banks. And its greatest negative – that it produces no yield – turns into an outright source of attraction when rival havens, such as bonds, carry outright negative yields. Treasury bonds have avoided negative yields, at least in nominal terms. But in real terms, arguably the single most important measure of the tightness of financial conditions, yields are negative. The U.S. 10-year break-even rate the projects what bond traders expect inflation to be over the life of the securities is now higher than the yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury note, meaning that the real yield investors make from those securities is negative. Real yields were negative until the Taper Tantrum, when they suddenly stormed into positive territory. Now real yields, like gold, have rethought the narrative of normalization that took hold of the market in 2013:  Barring a few days in the global scare that followed the Brexit referendum in mid-2016, yields are their lowest since Bernanke uttered the word "taper." All of this has happened despite current Fed Chairman Jerome Powell doing his best to channel his inner Bill Dudley and resist speculation that the Fed will inevitably cut rates radically in the months to come. Now to find a new narrative. More adventures in negative rate-land. Let me start with the obligatory mention that the U.S. Treasury yield curve inverted further on Tuesday, with 10-year note yields falling deeping below two-year yields. This anomaly has been extensively discussed, but there is one final market anomaly that is almost in a class of its own, and I thank Bespoke Investment for spotting it. It is not a spread that would have occurred to me to check. But Bespoke revealed, and I checked and they were right, that the dividend yield of the S&P 500 Index is now higher than the yield you can obtain from a 30-year Treasury bond. This is not the way things are supposed to be, but here is the chart:  This has happened only once in the post-Bretton Woods era, and that was during the tail end of the financial crisis in 2008-09. Back then, there was a run on stocks that caused their dividend yields to spike. This time, it's not that dividend yields have surged, but rather that 30-year bond yields have plunged. On the face of it, this is a sign that equities are a "buy." Bu they are not inexpensive relative to bonds, as we have heard many times from people selling stocks over the last decade. It is more useful to view this as a signal that negative yields are scrambling all the most basic assumptions of financial markets. In case you missed Bill Dudley. The Federal Reserve is an independent institution. Does that mean it can exert its independence by refusing to cut interest rates even if an ill-advised lurch toward protectionism brings the U.S. economy towards a recession? William Dudley, until recently the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Fed, opined in Bloomberg Opinion column Tuesday that it does. If the government wants to do something that stupid, Dudley argues, the Fed needs to do what is necessary to stop it from happening. Meanwhile I argued in a Bloomberg Opinion column at the beginning of this month, after tweet from President Donald Trump promising more tariffs on China was widely interpreted as a move to force the Fed into cutting rates, that "it has no choice but to offer insurance in the case that politicians do something really stupid that severely damages the economy." On balance, I still think that I am right. And the huge cast of central bank experts who reacted to Dudley's views were unanimously lined up against him. It is easy to get caught up in the increasingly nasty and personal invective that Trump is showering on Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, the man he nominated to run the central bank. It is a squalid but compelling story, and the increasing risk of an escalating trade war understandably concentrates all our minds. But there are broader principles at stake, and versions of this drama are playing out all over the world. The European Central Bank tried hard to step back during the euro zone's sovereign debt crisis in the hope that this would force politicians into making the needed political and fiscal reforms. The gambit failed, and the ECB instead promised to do "whatever it takes" to preserve the euro. The lasting legacy of that attempt to maintain orthodoxy has been the persistently sluggish European economy. In the U.K., the Bank of England is battling over whether to ease the path towards a no-deal Brexit. And in Mexico, the central bank cut rates earlier this month amid pressure from the country's newly installed left-wing president, but published a statement giving the government a laundry list of measures it needed to take "in addition to prudent and firm monetary policy." That provoked a presidential response saying that the central bank had offered "too much opinion." Tension between central bankers and elected politicians is normal, natural and usually healthy. Now, though, politicians of left and right find themselves wanting central banks to cut rates, and central bankers plainly seethe with a desire, which Dudley has now made public, to force politicians to do their job and make difficult decisions. And even if the consensus seems to be strongly against Dudley, the individual premises in his argument make sense. It is worth reading his piece in full, but here is a key passage: according to conventional wisdom, if Trump's trade war with China hurts the U.S. economic outlook, the Fed should respond by adjusting monetary policy accordingly — in this case by cutting interest rates. But what if the Fed's accommodation encourages the president to escalate the trade war further, increasing the risk of a recession? The central bank's efforts to cushion the blow might not be merely ineffectual. They might actually make things worse. Many commentators, myself included, have made exactly this point this month. The tweet from Trump unveiling new tariffs at the beginning of the month was very much an attempt to force the Fed's hand. Maybe the central bank could find a way to avoid being forced into helping the president do something stupid. Dudley's suggestion is as follows and similarly makes sense: Yet the Fed could go much further. Officials could state explicitly that the central bank won't bail out an administration that keeps making bad choices on trade policy, making it abundantly clear that Trump will own the consequences of his actions. Such a harder line could benefit the Fed and the economy in three ways. First, it would discourage further escalation of the trade war, by increasing the costs to the Trump administration. Second, it would reassert the Fed's independence by distancing it from the administration's policies. Third, it would conserve much-needed ammunition, allowing the Fed to avoid further interest-rate cuts at a time when rates are already very low by historical standards. Again these statements make sense as far as they go. Powell had to add the trade situation to the factors that might cause the Fed to act, and thus prompted the president into his most recent course of action. If we are unhappy with the outcome (and many of us are), why not explicitly rule out the president's behavior as an option? My own take on why these ideas do not hold is two-fold. First, the Fed has to look at its role as an institution and safeguard it. The Fed has responsibility for monetary policy, and a mandate to reduce inflation and unemployment. Many argue that even these responsibilities are too great to free them from tight oversight from elected politicians. To act further requires the legitimacy that only an election can provide. Recall that in the darkest days of the financial crisis, the Fed blinked at the notion of printing money to fund the entire rescue operation for banks. Instead the "TARP" plan went to Congress, and after being narrowly and dramatically approved, went on to be a critical element in eventually resolving the crisis. Going further, expressing an opinion on matters of policy beyond its remit, and even trying to force others to follow its prescriptions, would take the Fed into extremely dangerous territory as an institution. It does not have the necessary democratic legitimacy to do those things, and such actions would hasten a radical change for the Fed itself. For an analogy, look to the U.S. Supreme Court, which has long stayed somewhat out of the partisan fray despite being one of the three constitutional branches of government and despite handling intensely political issues. The current Chief Justice, John Roberts, appears to be working on the view that he needs to safeguard the court as an institution, and therefore limit the extent to which the court's conservative majority will strike down relatively liberal legislation. This is an intensely political and contentious issue in itself, but the need to conserve an important institution is rightly among his priorities. A second issue is moral hazard – the concept that insurance, or providing bail-outs, only gives incentives for more risky behavior. Letting Lehman Brothers fail in 2008 was intended to draw a line under moral hazard. In fact, it revealed that there was so much moral hazard in the system that the authorities could not possibly allow another large institution to fail. By trying to draw a line under moral hazard, it was an unwittingly revealed that it was now too late to do so. Refusing to cut rates in the event that the economy subsides amid a trade war might well fall in the same category. Like the Fed in 2008, or the ECB in 2012, the chances are that the Fed would have no choice but to buckle under and ease the situation. Ultimately, any decision that would deliberately as much pain as to cause a recession can only be taken by politicians subject to re-election. And it is those politicians who must ultimately take the blame – even for the actions of central bankers. Dudley's argument elicted a negative response, but there will be many in central banks who sympathize deeply with his core messages that central banks should not bail out politicians. Unfortunately, in the end, they have no choice. And those who hate central banks for their role in QE asset purchases and steadily creating the weird zero-rate world we inhabit today should perhaps direct their ire more at politicians. |

Post a Comment