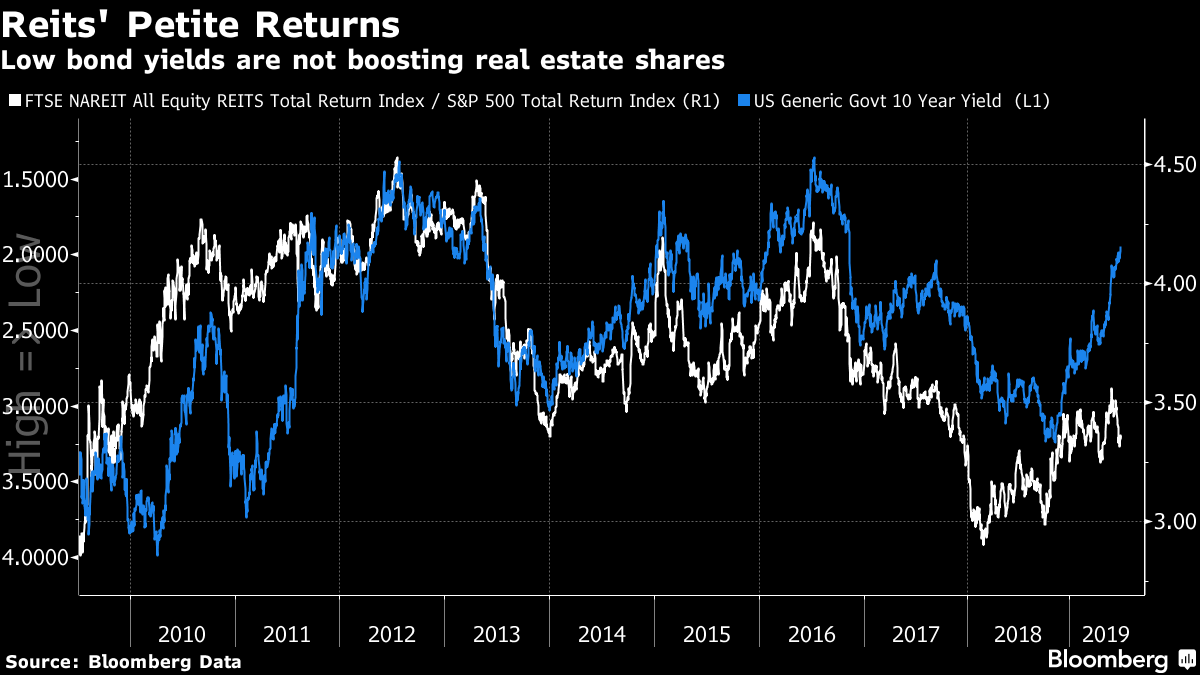

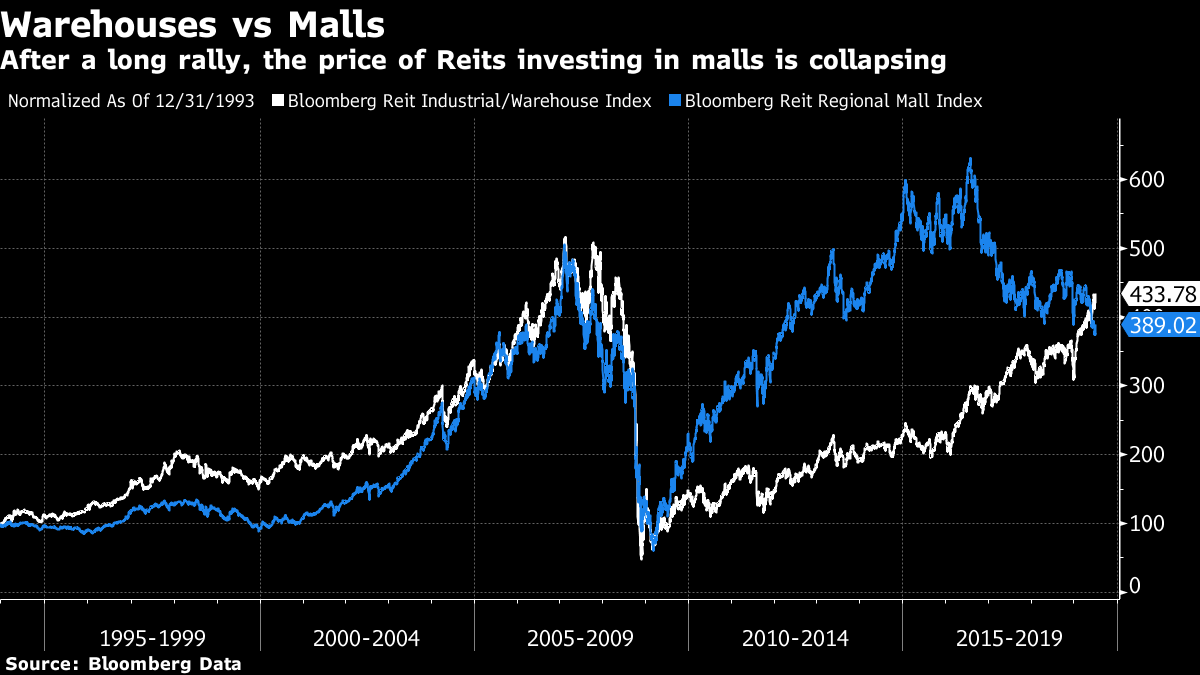

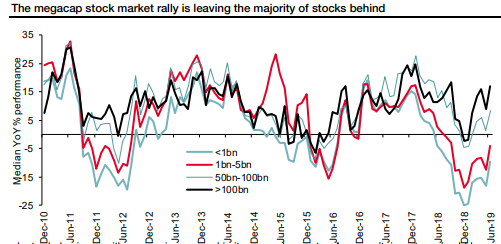

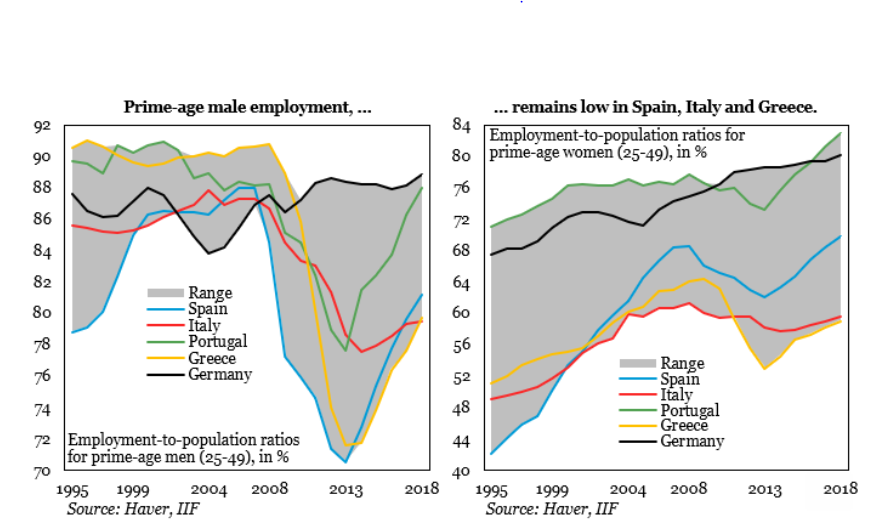

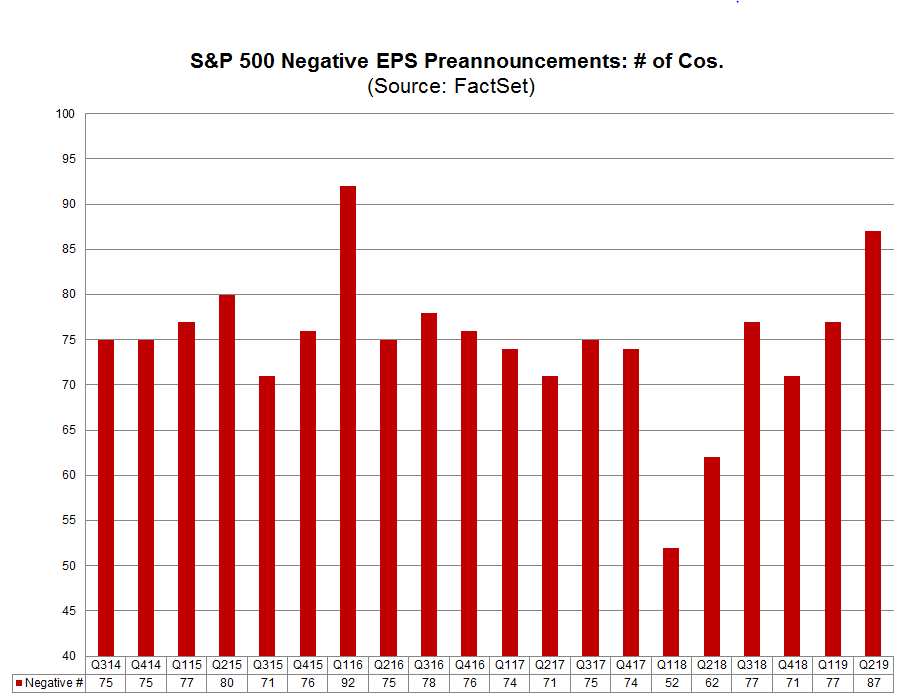

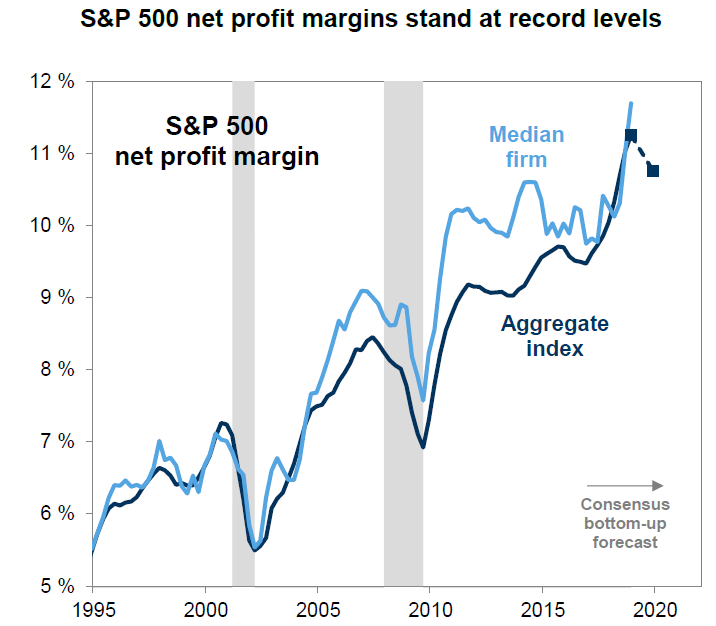

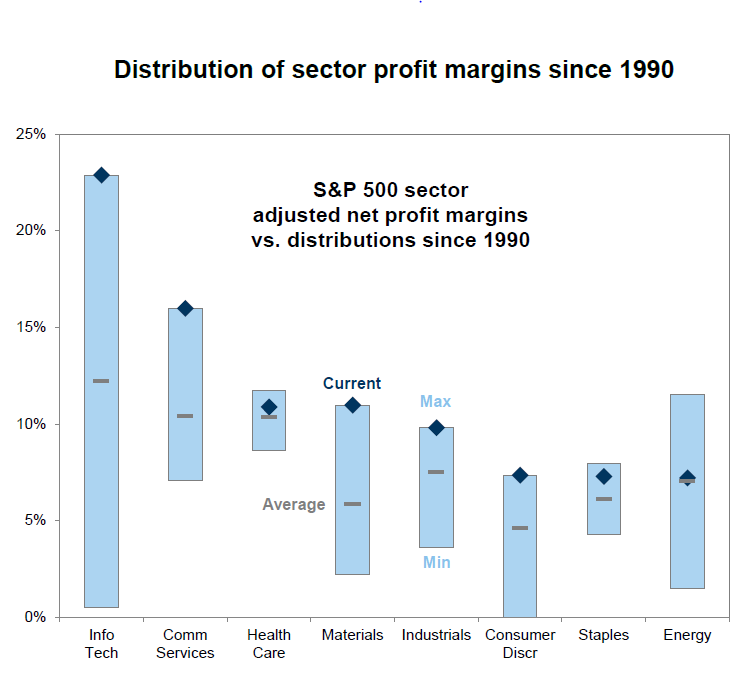

Happy Fourth of July. Americans have a fair amount to celebrate on this national holiday. Or at least, those who have money tied up in the stock market do. The main U.S. stock indexes closed at all-time highs on the eve of Independence Day. There are many reasons to find this surprising or disconcerting, which I will come to, but it is worth stepping back to look at the awe-inspiring way in which Corporate America continues to outpace the rest of the world. U.S. equities may be at a record, but the rest of the world is not. In fact, the U.S. has far out-performed the rest of the world since at least 1988, which is when MSCI launched an index of the world outside the U.S. The only times this was briefly not true came during the Japanese boom at the end of the 1980s, and the rage for emerging markets in the aughts before the financial crisis. Other than that, dominance has been total:  Whatever the reason, it is quite remarkable. Reason to enjoy the fireworks and barbecues. Real estate. One sector that has missed out on the U.S. stock market party is real estate. The sector has marginally beaten the market this year, but not by anything like what would normally be expected given the way long-term interest rates have collapsed. The great advantage of real estate investment trusts is that they have certain tax advantages that allow them to pay a reliable yield from their rental income, so they usually function as a pure play on rates, gaining when borrowing costs are low and falling when they rise. But not this year:  What is going on? The difficulties created by extremely low rates are part of the problem. And the sector is also being blighted by fear of "Retailpocalypse." Brick-and-mortar retailers are, as everyone knows, under threat. That means that the rents paid to REITs investing in malls and shopping centers are under threat – although the rents for the warehouses that are displacing them might be a little more secure. Over history, mall and industrial/warehouse REITs traded almost as if they were the same thing. But not recently:  Beyond the substitution effect of the "retailpocalypse," the broader reason for the weak performance of the REIT sector as a whole is more concerning. Lower bond yields are usually taken as presaging a rebound in economic activity, and thus boosting rents. This time around, real estate investors are more bearish about the economy. REITs investing in apartments and offices have also seen anemic performance. So the failure of real estate to rebound as rates fall can be taken as a symptom of negativity. Inequality. Another odd thing about this rally is that it has been led by big-cap stocks. The "size" effect has long been acknowledged, in that smaller companies are held to outperform larger companies in the longer term. That means that equal-weight indexes, where each stock has the same weighting regardless of its market value, tend to do better than indexes weighted by market cap over time. In the last quarter century, the only two exceptions came in the lead up to the dot-com crash of 2000 and to the financial crisis in 2008. These are not encouraging precedents, as the equal-weighted indexes are lagging behind again, although not to anything like the extent of those two great market breaks:  This is painful for active managers, as it grows harder to beat the market if the average stock fails to match the index. It also creates alarming incentives for everyone, as it leads to pressure on managers to pile into the stocks that are already biggest. This helped to create the "FAANG" phenomenon over the last few years. And this trend is not limited to the U.S. The following chart was produced by Societe Generale's quantitative equity department. It takes 17,000 stocks and splits them by market value. Small stocks have lagged behind throughout the post-crisis period, reflecting a reluctance to take risks, but the dominance of the biggest "mega-caps" is much more recent:  We are used to shocking inequality figures by now. This one applies to markets rather than humans. Of the 17,000 stocks covered in this universe, only 77 – less than 0.5% of the total - had a market cap of $100 billion or more. And yet they accounted for 27% of the entire market value of the world's stock markets. That sounds like an unhealthy degree of concentration, and it also implies a bull market in its last stages. Male resentment, European edition. Women are about to take over what are arguably the two most powerful jobs in the European Union. That could yet stoke what are already high levels of male resentment. The Institute of International Finance this week published this analysis of unemployment patterns in the main euro zone countries by gender. There is a huge range between countries even though they share a common currency. But the difference in experience for men and women is plain. Women's entry to the workforce started much later in Greece, while Italy and Spain started much later than it did in other parts of the developed world. In all of those countries, female employment is at least as high as it was pre-crisis. Meanwhile, in all three cases, male unemployment remains far lower than it was before the crisis.  The risks of serious social disorder is obvious. There are few things more dangerous than a large population of under-occupied and disaffected men. But the IIF also makes the point that there is more "slack" in the euro zone economies than might appear from the aggregate data. The overall rise in employment in these countries is more about a belated entry of women to the workforce than it is about a recovery in the labor market. And hence the jobs of the women now in charge of the EU Commission and the European Central Bank promise to be even harder than they look. Earnings prospects. One of the strangest things about the latest crop of stock market records is that they have come just as companies are trying to talk down their earnings prospects. Of course, they always try to manipulate expectations to an extent, but as this chart from FactSet makes clear, they are doing so to an unusual extent:  Added to this, falling bond yields show a fear in the market that economic activity will decline. This makes it hard to justify any great optimism that more profits will be coming from higher sales. So if investors do expect greater earnings, that implies that they must expect wider margins. And that seems greedy in the extreme. As this chart from Goldman Sachs shows, profit margins are in record territory. Usually cyclical, they have been on a barely interrupted rising trend ever since the crisis. And so, according to Goldman, the consensus is that they will fall.  Further, this phenomenon is virtually universal. As this chart shows, energy is the only major industrial sector where margins are not already at the top of their historical range:

People -like me - who have expected margins to revert to the mean have been proved wrong more than once during this expansion. But it does seem very strange to achieve a market record when always optimistic equity analysts expect margins to fall, while the bond market implicitly expects revenues to fall. Where exactly are the earnings going to come from?

These are good reasons for concern come Friday morning, when the monthly U.S. jobs report will help to focus attention on what is likely to be a day of thin trading. But there is no reason to worry about such things on the Fourth of July.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return?Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment