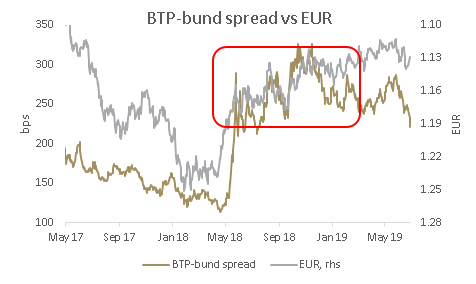

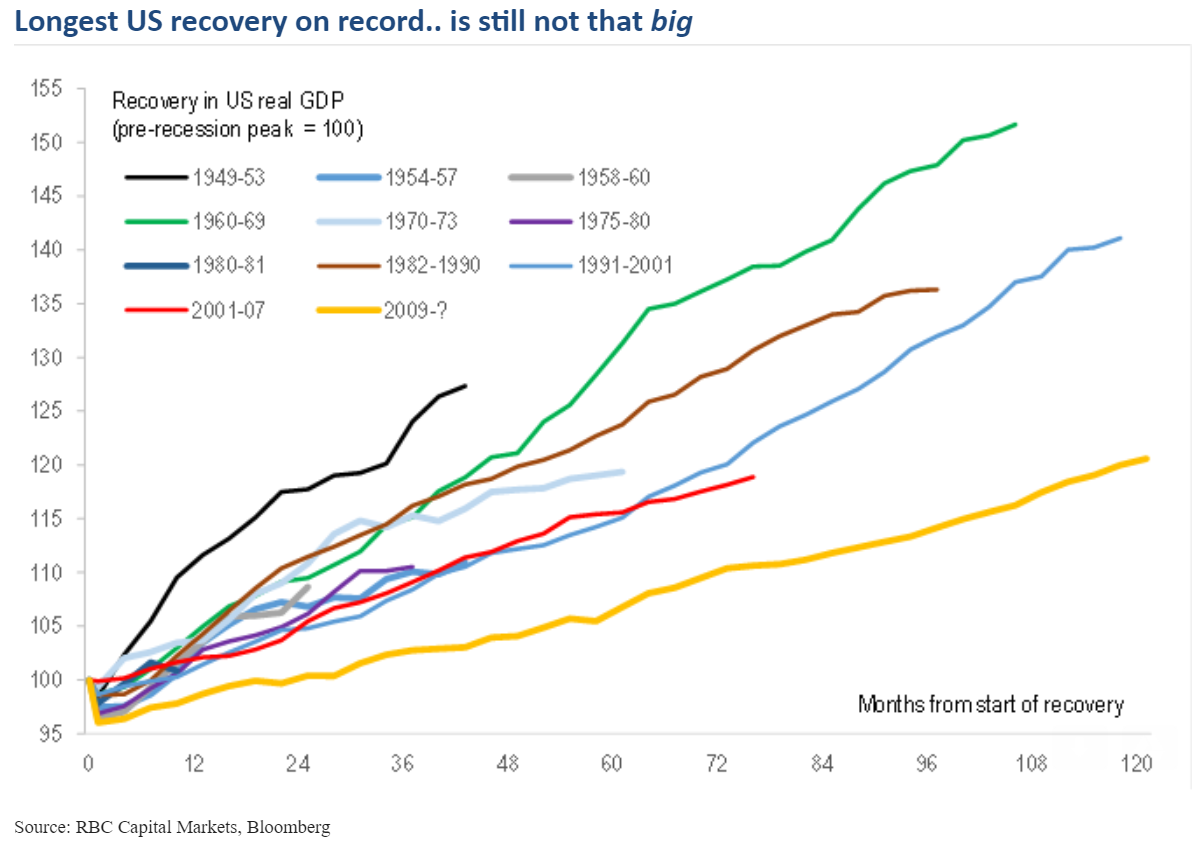

| Some people are just gluttons for punishment. Christine Lagarde served as France's finance minister during the financial crisis, and followed that up with a long stint running the International Monetary Fund. Now she is poised to take on a harder job than either, becoming only the fourth chair of the European Central Bank. The ECB has shown itself over the last decade to be arguably the only European Union-wide economic institution that actually works. With governments free to set their own fiscal policy and banking regulations, and more inclined to push the envelope with both, the ECB has been the only institution with the freedom to act decisively. It has been by far the most conservative of the world's main central banks for most of its existence, raising rates in 2008 as the crisis hit, and again, several times, in 2010. It held out against quantitative easing far longer than other Western central banks, true to the inflation-fearing DNA of Germany's Bundesbank. But it now finds itself with an overriding task of fighting deflation, not the inflation that brought down the German economy almost a century ago. The evidence shows that it's not succeeding. Even Germany itself is now in the midst of a true deflation scare.  But the ECB has another critical task, which is to keep the euro zone together. The euro is a political project above all, born of the anxiety of the last generation of leaders to fight in the Second World War to ensure that the continent should be bound together. And it requires a politician to hold it together. Mario Draghi, an economist, will be remembered chiefly for holding the euro together. Lagarde is not an academic economist, unlike her predecessors in this post, but she is an experienced politician who has acted as a sort of firefighter in a series of crises. That is what the job demands, and why it's probably good news that she has been nominated for it. She has also received a lovely welcoming present from Italy's ruling coalition of left- and right-wing populists, who have announced that they intend to set a budget within the limits agreed with the European Commission. Despite earlier noises to the contrary, it appears that they are not going to stage a confrontation with the EU about whether they should be allowed to launch a big fiscal stimulus. That means that neither the ECB nor the capital markets will be required to do the job of forcing the Italians into compliance. During a first stand-off over the budget in the winter, Italian 10-year bond yields briefly reached 3 percentage points more than equivalent German bund yields, while Italy's leaders made clear they could not bear to see the spread expand to 4 percentage points. Now the spread is as low as it has been since the coalition first took shape last summer, while yields have dipped below 2% for the first time in more than a year.  That means Lagarde should be free to deal with Brexit, which looks likely to happen at the end of October, and with deflation. If the Italians really do intend to make life a little easier, she should be grateful. This chart from BNY Mellon shows that the euro became tied to difference between Italian and German yields during the last budget stand-off. That was the last thing she needed this time.  There is a broader point about the EU. It is an unformed union of a group of different states, some of which strongly want to maintain independence, and which continue to have differing economies and differing ideas over how best to run an economy. The EU also has a dedicated group of politicians at its core who are desperate for unification to move further. And its financial system appears to offer its most enthusiastic leaders their best chance to bind the disparate countries into a convincing union. In all these respects, the EU is just like the U.S. when George Washington was president, as Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson staged an epic political fight over the kind of union that their new country should become. Anyone who has seen or heard the musical of Hamilton's life by Lin-Manuel Miranda (and if you haven't, you should — it's brilliant) would know this. And that might arguably provide some hope for the EU's future. The way in which the EU's top jobs have just been carved up, with one of German Chancellor Angela Merkel's best friends running the EU commission while other large countries split the remaining posts, is indefensible by almost any measure. It's the kind of horse-trading that enabled the Brexiteers to persuade Britons to vote to leave. But the politics at the birth of the U.S. were identical. One of the most famous songs in the musical is "The Room Where It Happens" and covers the meeting between Hamilton, Jefferson and James Madison at which the two Virginians gave Hamilton the system of Treasury bonds that he wanted — Jefferson was opposed even to the notion that governments could issue bonds that could subsequently be traded — in return for a promise from Hamilton that they could locate the nation's capital within the boundaries of Virginia. It was in many ways, according to former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, the first federal government bailout of the states. And it is very reminiscent of the EU deal in which the ECB resides in Frankfurt, but is run by a series of non-Germans. And, of course, there was plenty of horse-trading over the U.S. Constitution. The analogy is not necessarily reassuring. The U.S. did have a horrific Civil War in its future. But maybe we should derive some hope from the EU's ability to get something done after what at first appeared to be a shocking reverse for Merkel and Germany. Big projects, up to and including the establishment of the U.S., start this way, in rooms to which most of us have no access. Wider still and wider. The U.S. economic expansion became the longest on record this week. That is quite something, particularly given the utter gloom that pervaded a decade ago. Further, it has been achieved under two almost polar opposite presidents. But there is a reason why many still find the expansion unsatisfying, and it is illustrated beautifully by this chart from RBC Capital Markets, which compares the length of different economic expansions by time with the total percentage growth that was achieved while they lasted.  The expansions now associated with Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton were shorter, but more robust. Couple the slowness of this recovery with the well-documented deepening of inequality and we can see why this expansion is much less loved than its predecessors. China's red flags: A warning from Japan. As a reminder, this month's book club selection is "Red Flags" by George Magnus, about the problems facing China. There are three weeks to go until we will discuss it online, so please try to give it a read if you can. It's well worth it. Meanwhile, one reader alerted me to the risks inherent in geopolitical books that attempt to predict the future. This book was widely read in 1992:  There has, of course, been no war between the U.S. and Japan since then. But it was not just that book. Robert Reich, in a review for the New York Times, uncovered an entire genre of books predicting bad things from Japan. One of my favorites was this one, "The Shadow of the Rising Sun":  That one was published in 1990. The following passage from the blurb suggests that history has not panned out quite as expected at the time: Boasts about the victory of free-market capitalism in the wake of the collapse of the Communist state-directed system are premature and distract attention form the necessary recognition that it is the Japanese combination of the free market with a strong central state and a highly skilled professional bureaucracy that has really proved triumphant in our modern age of advanced technology. Only if we fully understand the reasons for Japanese success and American decline can we begin the arduous but crucial task of reconstructing the American polity to give it the power required to formulate and implement a national industrial policy that can regain for the United States its preeminent place among the world's industrial powers. The alternative, Dietrich describes in a chilling scenario, is a "Pax Nipponica" that will find America playing second fiddle to Japan with economic, cultural, and political consequences that will make Britain's eclipse by the United States earlier in this century seem mild by comparison. A good contrarian would have said that all these books suggested that it was time to short Japan and buy America. So, for those interested, this is how the Nikkei 225 and the S&P 500 have fared, in dollar terms, since the beginning of 1990:  There are red flags over China, and there were also red flags over Japan 30 years ago. History has a way of making us look silly. We should study the travails of contemporary China, and its troubled relationship with the U.S., in that light.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return?Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment