Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter making the case that the purportedly pessimistic Treasury traders could actually be wearing rose-colored glasses too. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter

Fed's Half-Empty Glass

A defining characteristic of post-crisis central banking has been the asymmetric concerns about economic downturns. And with major economies closer to the lower bound for benchmark interest rates (if not still lingering there), and questions surrounding the ability of monetary policy to stimulate growth, that shouldn't come as a surprise.

Even though the Federal Reserve has won the race away from the lower bound, Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues are not immune from the need to look at the glass as half-empty, not half-full. This sets the stage for next Wednesday's hotly anticipated policy decision: a half-empty glass supports the case for refilling the punch bowl – if not now, then soon.

The trade war – and its potential resolution should Presidents Xi Jinping and Donald Trump reach a détente at the G-20 Summit – is the chief two-sided risk that may keep the central bank "patient" for now, even if that word is scrubbed from its statement. But even there, the damage may be done: chief executives' confidence has been seriously dented, and a deceleration in global activity even before the trade clash flared up strongly suggest that the downside risks to growth outweigh the potential for a boost to capital spending in the event of a resolution.

The asymmetries relating directly to the Fed's dual mandate are more glaring. The central bank has often worried about non-linearities with regard to inflation. If downside risks are rising, it's time to take the same approach for the other half of the mission: full employment.

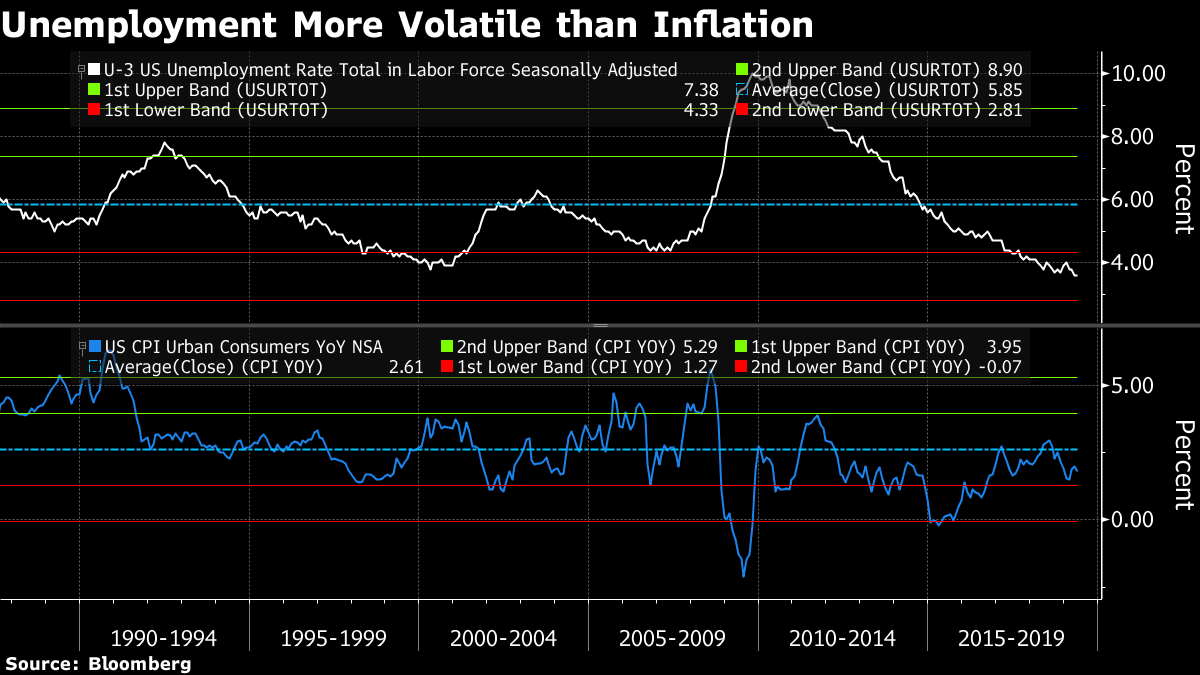

The concept of a non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment has been the driving force behind the tightening cycle. Yet risk management, in the current context, would argue for worrying about the non-linearity of any accelerating upturn in the unemployment rate. History suggests that when the U3 measure of joblessness goes up, it doesn't go up just a little, and the move isn't slow.

After all, since Alan Greenspan's tenure atop the Fed, the unemployment rate has been more volatile than the inflation rate, judging by their relative standard deviations.

Along these lines, Skanda Amarnath of Employ America makes the case for the Fed to deliver a 50 basis point cut at the June meeting. The job market is less robust than it appears, he argues, pointing to a rollover in prime-age employment growth and softer increases in gross labor income.

"Bad stuff happens quickly (negative skew) and the Fed is in a strong position to prevent, rather than mitigate," he concludes. "Reversing cuts is not a cost-free exercise but given the nature of the Fed's problems (e.g. low inflation, underestimation of maximum employment, low nominal growth, low interest rates), there is one side on which it should clearly err."

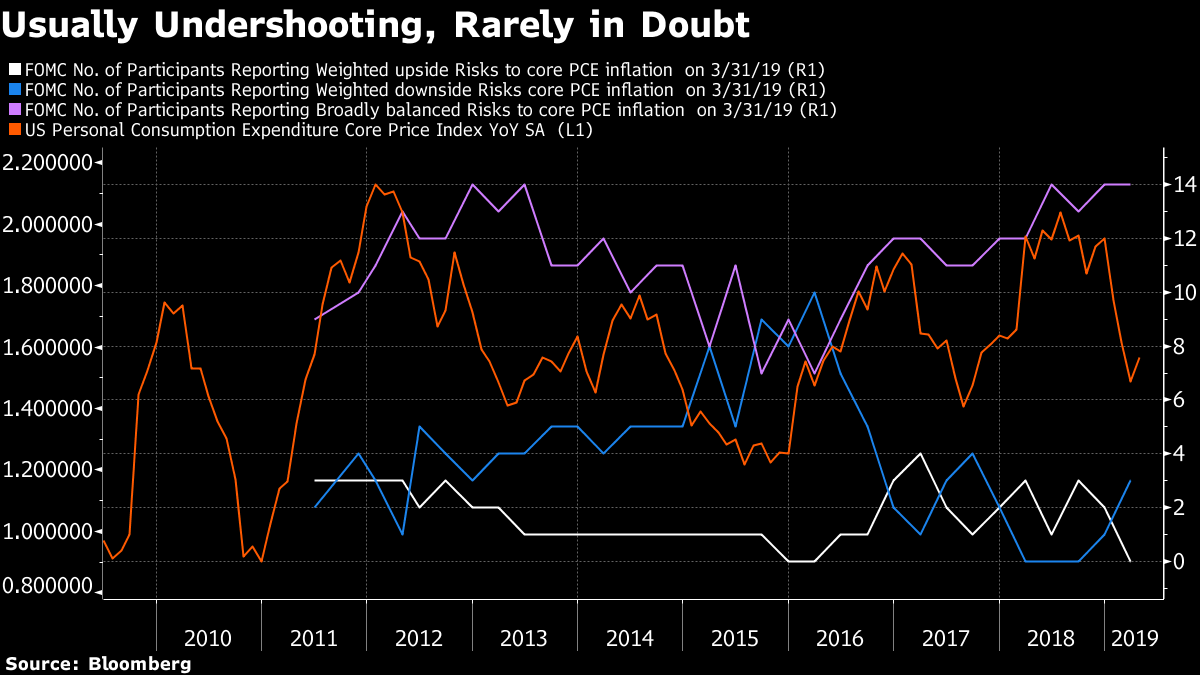

Right now, inflation is fairly moribund – despite a reversal in some of the "transitory" sources of subdued price pressures highlighted by the Fed chair. Consumers' expectations for inflation are sliding. And traders aren't convinced it will pick up, either.

It's worth remembering that Fed officials have been persistent and asymmetric in their erroneous forecasts for the core PCE gauge inflation this cycle, but rarely in doubt.

Virtually every part of the Treasury market understands, appreciates, and reflects these realities. Next week, we'll see if Powell does as well. Granted, his task is far from easy: if the June dot plot and forecast revisions point to softening in the U.S. economy and the need to lower rates from current levels, there will be confusion as to why the central bank isn't taking proactive action to allay the soft patch. However, if growth and inflation forecasts remain relatively unchanged and the median estimate for rates doesn't suggest easing is in the offing, the central bank risks another tone-deaf "transitory" or "autopilot" moment.

In a webcast on Thursday, DoubleLine's Jeffrey Gundlach was asked if the Fed would be capitulating to Trump if they lowered rates. No, he said, the central bank would be capitulating to the bond market. Weeden & Co. chief global strategist Michael Purves has similarly referred to the bond market "taunting the Fed" at current pricing.

Given the limited sample size of U.S. downturns, it's completely fair to argue that things are different this time, with a benign outcome for the American economy on the cards even in the absence of rate cuts.

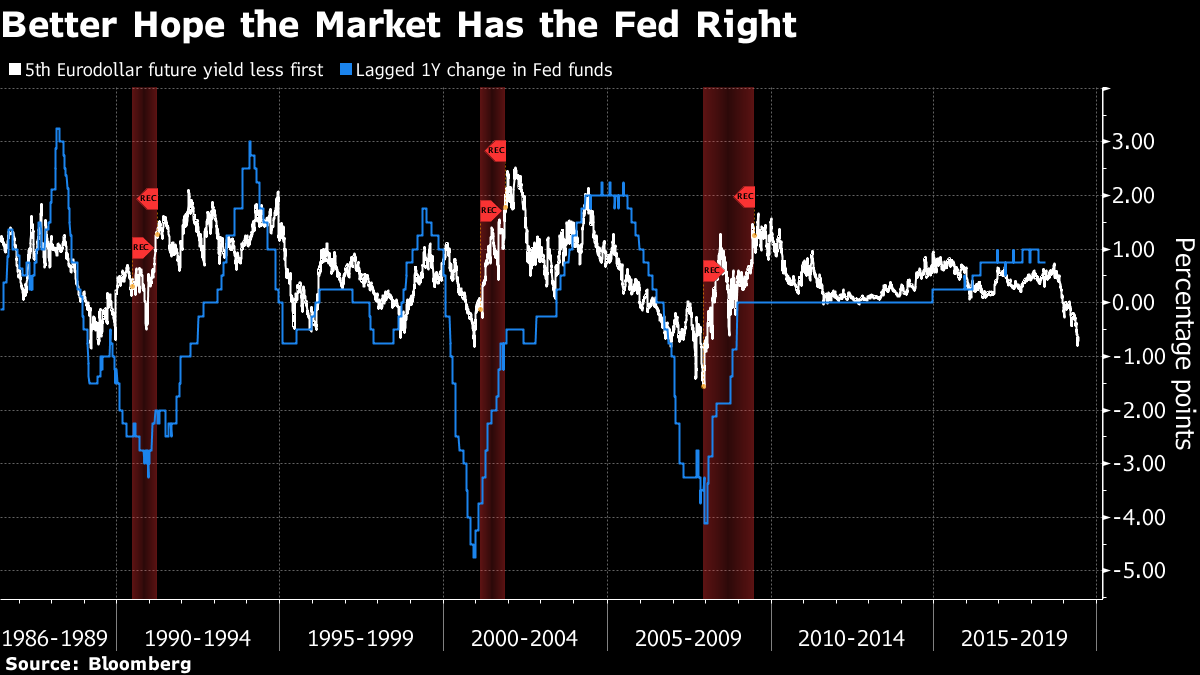

But the scariest thing for financial markets and the U.S. economy could well be if the bond market is wrong. For all the talk about how the bond market always gets the Fed wrong, there's not been so much in the other direction.

History says whatever the Fed needs to deliver to offset headwinds is at least what the market's thinking or more. To be specific, when the yield spread between the fifth and the front-month Eurodollar futures contracts (a proxy for one-year market-implied easing) is this negative, the Fed has either delivered that much accommodation or much, much more.

Close-to-the-Money Put

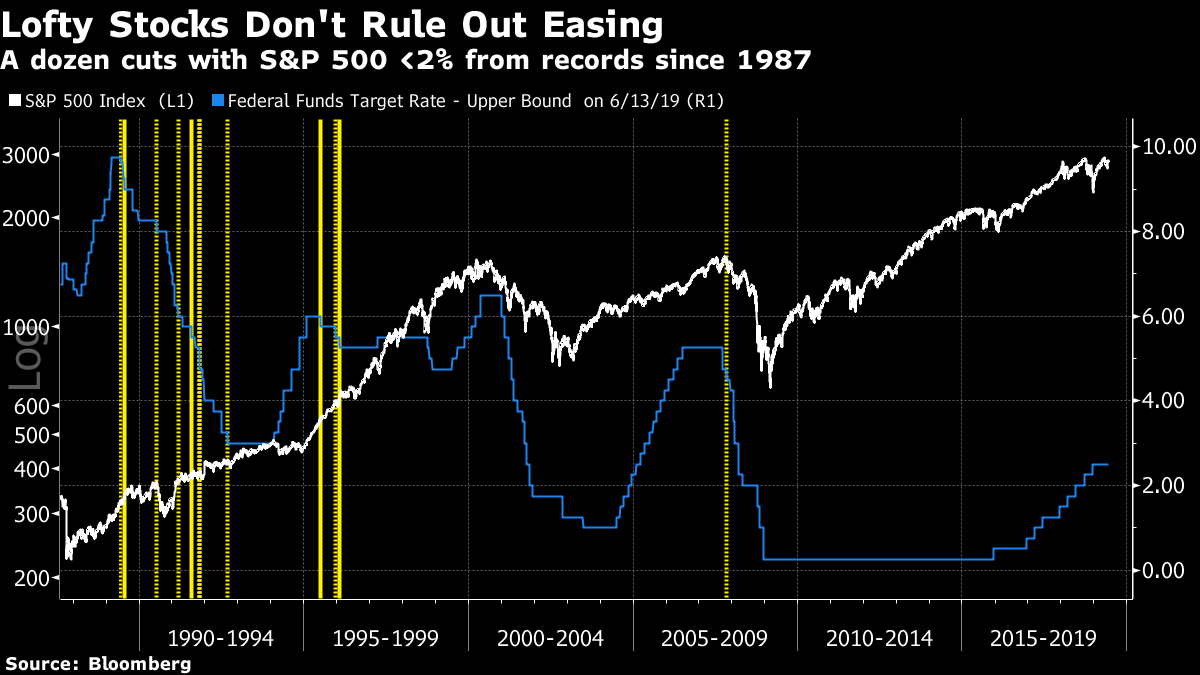

Hold up, how can we be talking about rate cuts when U.S. stocks are within spitting distance of all-time highs?

Well, consider a not-so-short history of the Fed doing just that. From Greenspan through Ben Bernanke, it's happened a dozen times.

June 1989, July 1989, July 1990, March 1991, August 1991, October 1991, November 1991, September 1992, July 1995, December 1995, January 1996, and October 2007.

Dotted lines on the below chart denote occasions when the S&P 500 was in a drawdown of less than 2% from a record, while solid lines indicate that stocks closed at a record the day of the reduction.

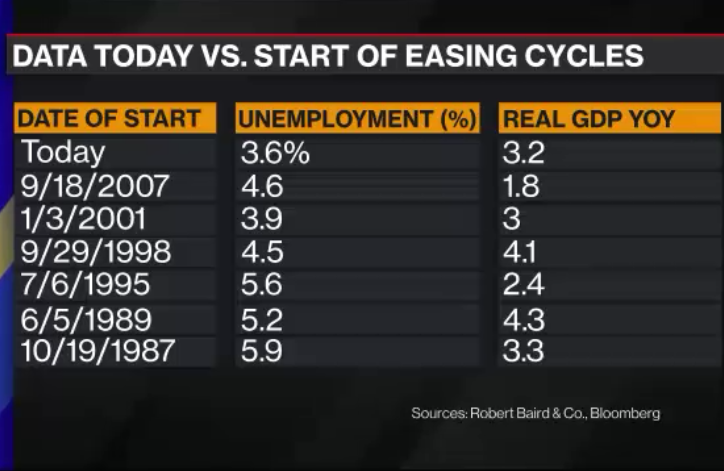

The economic conditions and state of the stock market at the start of the last six easing cycles have a fair degree of dispersion. This speaks to the discretion central bankers have in acting and responding to perceived changes in the outlook. In fact, their framework tells them they have to be forward-looking, since monetary policy is said to affect activity with long and variable lags.

The dispersion around one, three, and 12-month forward returns following the commencement of the easing cycles since 1987 is even more extreme. The two instances in which stocks rose over all of those timeframes were 1995 and 1998, again, the episodes most commonly trotted out as analogues for the current situation.

Strategists at UBS Group AG, however, rightly advise against such historical comparisons.

"Rate cutting or hiking cycles are too diverse across time to produce consistent results from financial markets," they write. "Understanding the Fed's impact on future data is far more important than studying average results of the past."

In equities, there's almost somewhat circular reasoning going on: equities are resilient in part because investors have priced in Fed easing, and investors expect the Fed to ease because they believe stocks will fall if they don't.

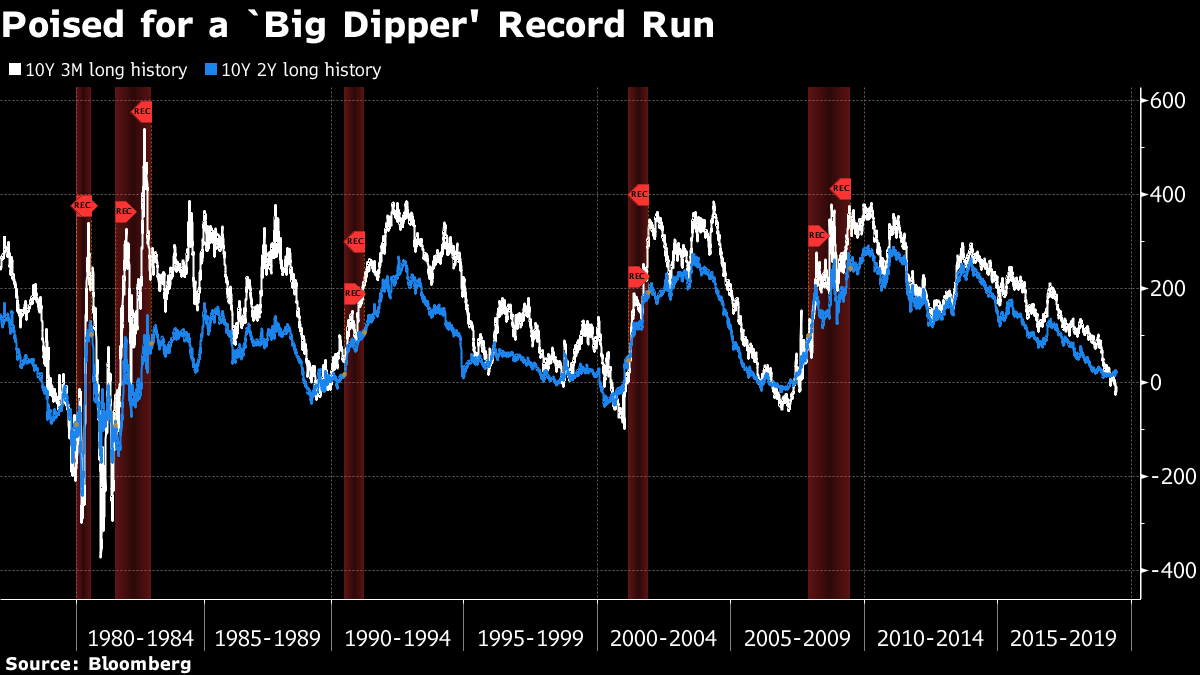

The bond market's high degree of confidence that the Fed's easing will contribute to a soft landing is best shown by the combination of the inversion of the three-month, 10-year curve (implying that easing is in the offing) with a positively sloped two-year, 10-year curve (suggesting it won't last long). If this "Big Dipper" yield curve shape persists up until next week's Fed meeting, it will mark the longest such run on record.

To this end, traders are alreadypositioning for the hike that comes after the longed-for cuts.

The cross-asset dynamics bring to mind remarks delivered at the recent Fed conference by Annette Vissing-Jørgensen of the University of California, Berkeley:

"Monetary policy literature has not focused enough on such effects of removing tail risk because of its focus on fed funds futures (and Treasuries). If a promise of a lower policy rate in the bad state lowers probability of bad state, you may not see the accommodation in futures rates. They could increase, since the policy rate in the good state is high. The stock market unambiguously goes up. Removal of the bad state is good for stocks via both lower risk premium and higher expected cash flows."

(Recall, for instance, how quantitative easing programs were often greeted with rising yields – as their signaling effects helped give investors comfort that worst-case scenarios would be avoided.)

But in this case, strategists reckon the Fed has to do more than talk, but follow through on its newfound openness to easing in order to prevent a market drubbing that ripples through to the real economy.

"If they don't ease this year, there may be an effective tightening of financial conditions as is currently inferred by the deteriorating growth backdrop," writes Jeremy Hale at Citigroup Inc.

Post a Comment