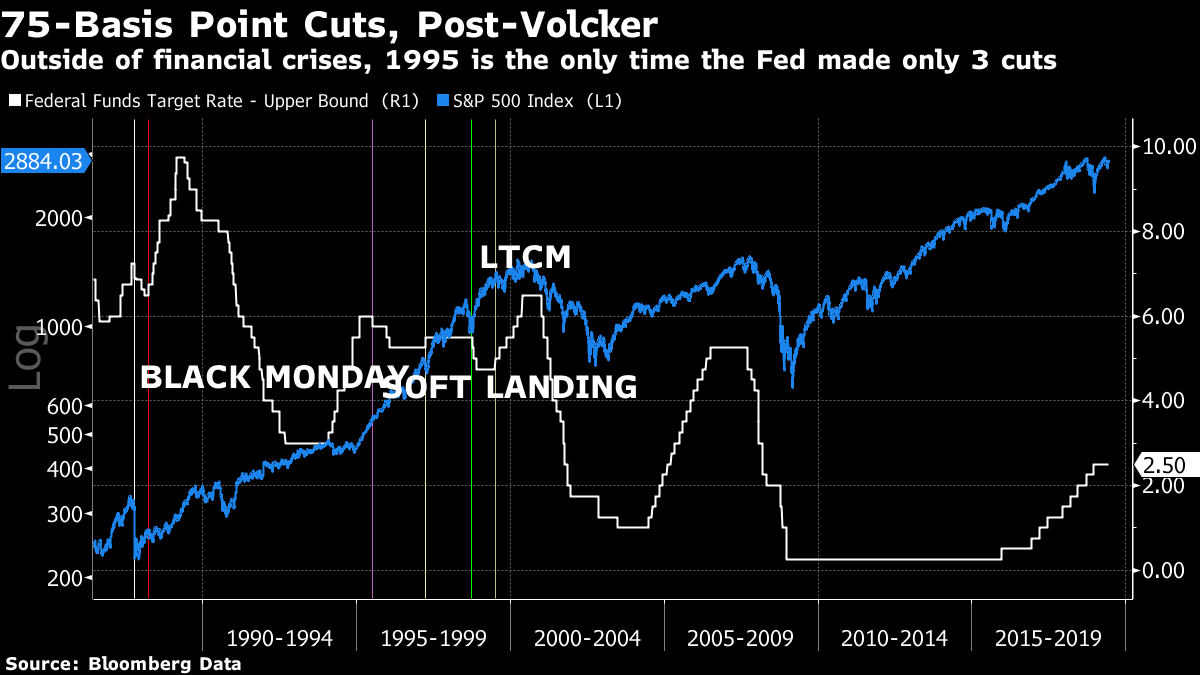

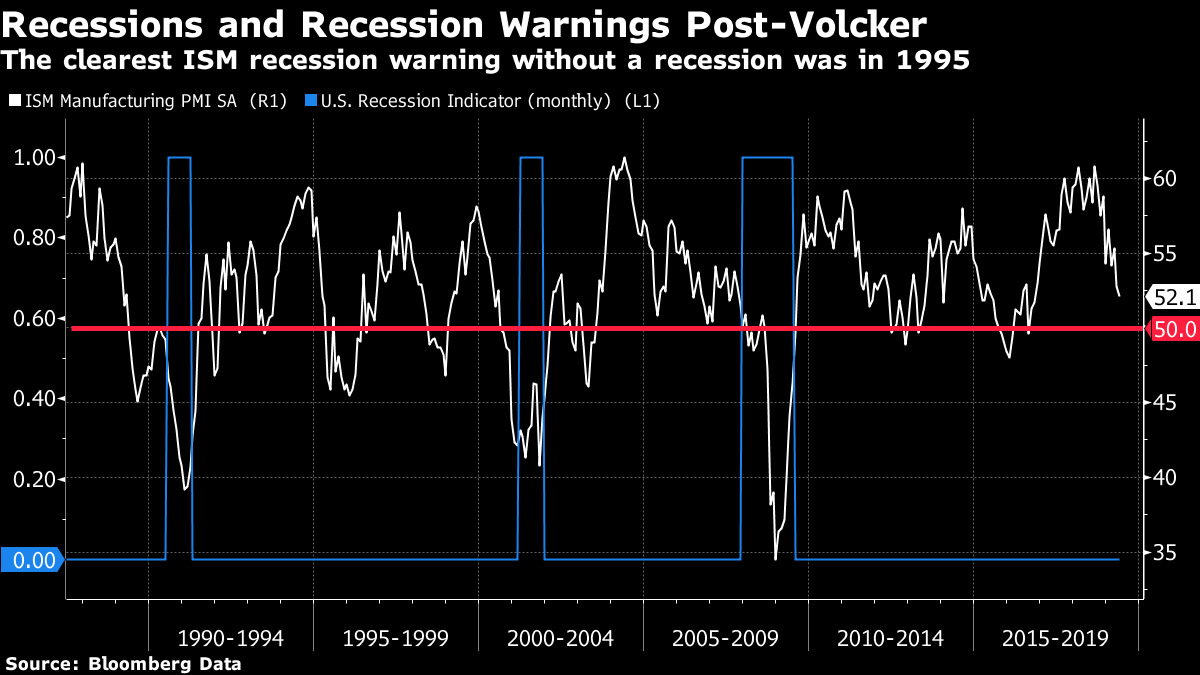

The Market Expects the Fed to Do Its Duty The market expects. President Donald Trump's threat to impose tariffs on Mexican imports has come and gone, but the market remains convinced that the prospects for the Federal Reserve have changed utterly in the last two weeks. If the Fed funds futures market is to be believed, the odds now favor three 25 basis point cuts between now and the end of the year. Nobody gave such an outcome the time of day until a few weeks ago: One argument is that the Fed could use an "insurance cut" to calm things down if the trade conflict intensifies. The bond market plainly expects lower rates. The latest economic data has been disappointing, particularly on U.S. jobs, but these figures are notoriously noisy. The most likely explanation for the market's newfound confidence that the Fed will cut drastically comes from inflation breakevens. In the U.S., 10-year expectations are almost at their lowest since Trump's election ushered in hope of renewed economic growth. Germany, and Italy in particular, have plumbed new depths. And even in Japan, years of stimulus from "Abenomics" have failed to stop inflation forecasts from falling further from an already low base:  The problem with this is that a cut of 75 basis points implies that something is dreadfully wrong. Generally, when the Fed cuts that much, it does not stop for a while, and a recession results. And yet it is hard to find strategists predicting an imminent recession. And the market seems to work on the assumption that the central bank will cut rates three times and then stop. Since the end of the Volcker era, the Fed has made three cuts and then stopped only three times. Two of these were responses to significant financial incidents — the Black Monday stock market crash in 1987 and the meltdown of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund in 1998. That leaves only one precedent in the last three decades for what the market is expecting. That is the period in late 1995, when the Fed cut rates three times and engineered a "soft landing." By the time it raised rates again, in early 1997, Chairman Alan Greenspan had famously sounded the alarm about "irrational exuberance."  Assume the bond market is not pricing in an imminent stock market crash that forces the Fed to cut rates aggressively. It appears to be expecting a cut along the lines of 1995, when the economy did indeed appear to be teetering on the brink of a recession. In the post-Volcker era, it was the longest period when the ISM manufacturing survey fell below the level of 50 (taken to indicate a contraction) without the economy subsequently falling into a recession:  My colleague Ye Xie drew attention to a note from the respected British economist Gavyn Davies, which you can find here, showing the parallels with 1995. He also shows that Greenspan regarded the incident as one of the finest of his career, but also a scary one, ina passage from his book: We were groping through a fog . . . The soft landing of 1995 was one of the Fed's proudest accomplishments during my tenure. The Fed got away with it that time. And, of course, the stock market surged so violently in response that it unleashed irrational exuberance, which Greenspan fatefully failed to contain. That was surely one of his least proud accomplishments.

In hindsight, 1995 was a brief slowdown in a period of fantastic sustained growth and also a sustained bull market in stocks. It would be really wonderful if we could have that again.

Is it fair to expect it? Maybe, but I would offer the following cautions:

- Rates start from a much lower base this time. The proportionate impact of a 75 basis point cut, so soon after the Fed had been telling the market that it expected to keep hiking this year, would be profound.

- A big part of the story of 1995 was that the Fed had overtightened the year before, prompting a bear market in bonds and financial upheaval from Orange County, California, to Mexico. The recent increases were far better telegraphed.

- Even though the economy does not feel as strong as it did in 1995, the economic data seems far further from a recession than it did then. A few more months of declining job gains and ISM readings may change that, but those bad numbers need to happen first.

- If the data does give the Fed clear cause to cut, the history of the last three decades suggests that it will need to keep cutting, as it did in 1990, 2000, and 2008 — when there were recessions and bear markets.

- There was underlying juice for the economic expansion in 1995 — so much, in fact, that Greenspan started talking about a "new economic paradigm." Cheap Mexican labor was pouring into the country; the internet was beginning to revolutionize productivity; equity markets were supported by flows from baby boomers approaching retirement; and everyone was basking in the "peace dividend" after the end of the Cold War and relaxing in a new era of international harmony. Suffice it to say that those conditions do not adhere today.

None of this means that this couldn't be a repeat of 1995, but in making its current wager, the market is betting on an awfully positive group of circumstances coming together once more. China Reactions I am pleased to say that a lot of people are already offering their own commentary on China and George Magnus's book "Red Flags." I will mention two for now.

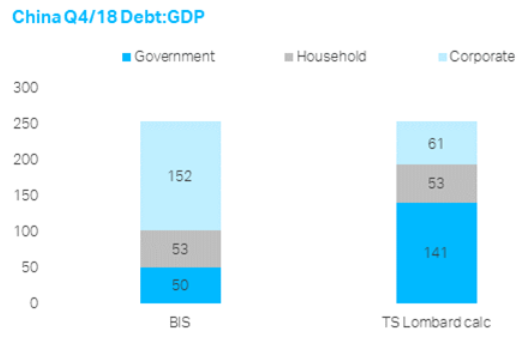

First, Rory Green of TSR in London points out that the usual debt-to-GDP figures generally "vastly exaggerate the level of corporate debt by including debt from local government financing vehicles, centrally controlled state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and provincial SOEs, all of which are at least implicitly backstopped by the state." Making this adjustment drastically changes the composition of China's debt:

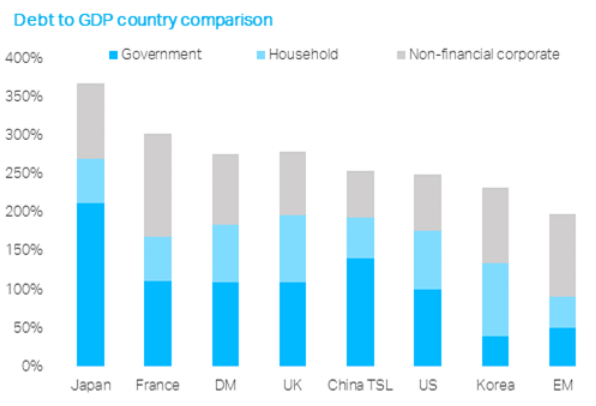

It also makes China's debt profile look similar to many other countries — although the speed with which the debt has grown should still, in my opinion, be cause for great concern:  The bottom line remains that with the Chinese government in charge of the currency, the banking system and the state and corporate sectors, a repetition of a Lehman-style credit implosion in China should be impossible. (Although the possibility of this debt overhang forcing a prolonged period of much slower growth remains alive.) On the yuan, I found this point from Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital very interesting: The China currency is getting traction and could displace the USD in Asia (China's stated aim). What is not well understood is that China still has an immature financial system which forces it to accumulate USD (from trade which is USD denominated) and manage them centrally via the State. Domestic institutions, unlike in the West, have predominantly Yuan liabilities and so cannot afford to take this forex risk. China initially used forex reserves to buy US Treasuries, but now invests via FDI, e.g. Belt and Road. This external infrastructure programme will help to establish the wider use of the Yuan across Asia and get China off the US dollar hook. Do not underestimate the value of this seigniorage for growth. He could even back it up with an anecdote: I attended the LSE launch of George's book. There I met an ex-Central Bank Governor from Central Asia who shared my scepticism about George's Yuan point. "I will show you," she said and pulling out her iPhone she shared a photo of her at a formal signing ceremony for a several billion Yuan swap line with the Chinese Finance Minister. Proof she claimed that this underlying use of the Yuan is already the reality across Asia. Food for thought. All responses about this book are welcome — particularly if you use the IB chat room we have set up for the purpose on the terminal. Let us know at authersnote@bloomberg.net and we can get you access. "Vincero!" Or, Trump Sings Pavarotti

Finally, a moment of inspiration brought to you indirectly by David Kotok of Cumberland Associates, along with a slightly painful memory. Kotok headlined his latest market missive "Turandot," after Puccini's last and arguably greatest — but incomplete — opera. It is set in China. The analogy works, Kotok says:

Why do I start a commentary about China and the Trump Trade War by invoking an opera to serve as a metaphor? The reason is that there is a history lesson. Puccini wrote the entire opera except for the final duet. He died on November 29, 1924, before completing the text. Franco Alfano was commissioned to complete the opera, but conductor Arturo Toscanini did not like the result. At the opera's premiere on April 25, 1926, Toscanini stopped in the middle of the third act and announced to the audience, "Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died." (Source: Richard Russell, executive director of Sarasota Opera) The operatic drama underway features Trump and Xi. The setting is China and also Washington. Instead of the three riddles of Turandot, we have tweets back and forth between the US and in China. Sadly, though, the current version is not a comic opera. The closing duet is not yet written. It does seem to be a good precedent (Trump used the song at campaign events). More concerning, we lack a Toscanini-like figure to call the whole thing off if the conclusion the two leaders come up with is not to his satisfaction. Perhaps more sadly, however, the trade war so far lacks any high moment of drama to match "Nessun Dorma" ("Nobody will sleep"), the show-stopping aria from "Turandot" that made Pavarotti famous and became the theme song for the 1990 World Cup in Italy. It's extraordinary. Here it is:  Why do I find this painful in any way? In a younger life, I trained to be a classical singer. I was never good enough to give up my day job, but I did get to have a lot of fun along the way, including once singing in Pavarotti's backing choir at an open-air concert he gave in 1993. We rehearsed what was to be his final encore with him, which was "Nessun Dorma." The song was by far his most famous and had been No. 1 in the U.K. But he was having trouble with his throat and did not sing the amazing high note on "Vincero!" at the end. At the end of the concert, he still did not seem to have confidence in his high notes. After two encores, the plan was to move on to "Nessun Dorma." Instead, he turned to the orchestra and made an emphatic gesture for them to leave. In their tuxedos and their long dark dresses, the instrumentalists literally ran off the stage. The concert was over, and the audience was not going to get "Nessun Dorma." Pavarotti was one of the greatest singers ever, but this is still a painful memory. He could have made a charming apology. He could have explained. Instead, he left his fans without their showstopper, and without an explanation. An audience deserves more respect. Let's hope the Trump-Xi duet has a better ending. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment