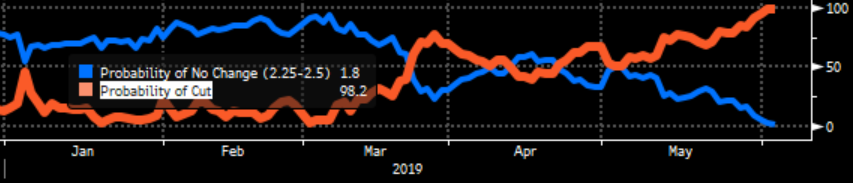

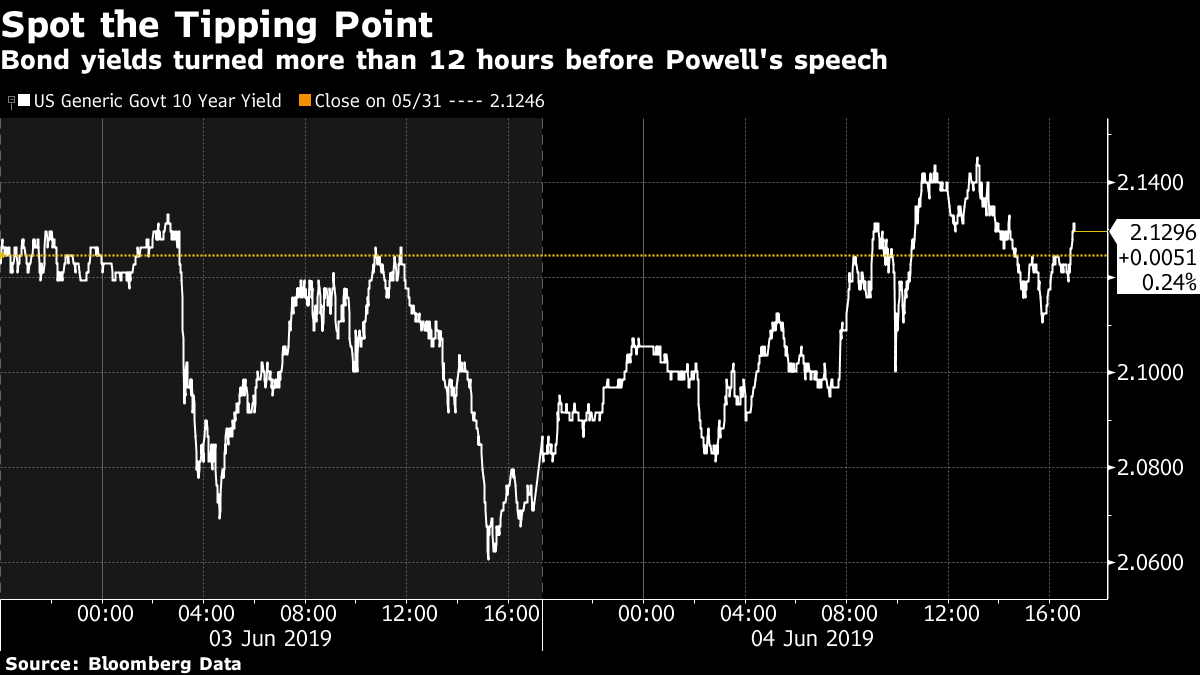

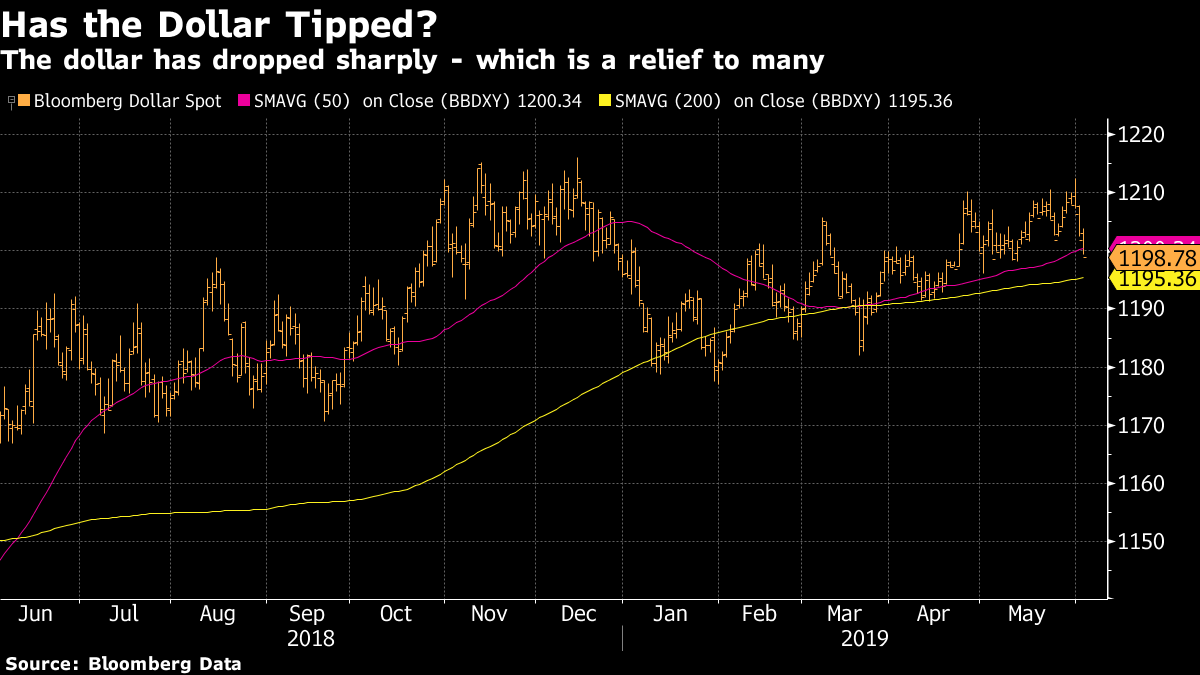

Tipping point. Did Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell really just turn the markets around, sparking the greatest one-day rally in the S&P 500 Index since Jan. 4? Was this a tipping point? I am dubious on the first, but think there is something to the second. Powell opened a conference in Chicago on Tuesday by commenting that the Fed was ready to take action to stop the escalating trade conflagration from damaging the U.S. economy. "We do not know how or when these issues will be resolved," Powell said. "We are closely monitoring the implications of these developments for the U.S. economic outlook and, as always, we will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion, with a strong labor market and inflation near our symmetric 2% objective." That statement implies that if the trade problems intensify, there will be interest-rate cuts. From the man who leads and steers the Fed, these comments are significant, but they do not commit the central bank to anything and still provide him plenty of wiggle room. Moreover, the markets most directly affected by monetary policy were already pricing on rate cuts as a virtual done deal. If anything, Powell was more hedged in his comments than those trading in the federal funds futures market might have hoped. If futures are to be believed, the chance of a rate cut by the final meeting of the year in December was already more than 98%, even before Powell spoke. This is a screen shot from the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function gauging potential rate moves by year-end:  Powell's words referred to the probable direction of rates. And according to the market that gauges the probable direction of rates, his words made no difference. Not much of a tipping point. Now, take a look at how the 10-year Treasury note yield moved over the last two days. It does not make sense to me to view the Powell comments as a key moment of capitulation, or as a trigger for a big market turn.  There is another narrative to suggest that the market had a reason to shift Tuesday. It comes from the budding trade conflict between the U.S. and Mexico. During the day Mexico's president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), said he believed that the countries could reach an agreement before threatened tariffs are due to be imposed next week, while his foreign secretary Marcelo Ebrard put the odds of avoiding tariffs as high as 80%. Only six months ago, the predominant narrative was that AMLO was a dangerous leftist whose word could not be trusted. Fear of him drove a sharp run on Mexican assets. Ebrard was his chief of police and then his successor as mayor of Mexico City. So did markets really turn on the say-so of these two men, and their predictions of success in a negotiation with the notoriously unpredictable President Donald Trump? If they did, the cognitive dissonance must have been dreadful. A better explanation is that our troubles remain roughly where they were on Monday morning, but markets reached a point by the close of trading that day that no longer made sense. As a result, a number of long-running trends collapsed under their own logic. They had reached what Malcolm Gladwell might have called a tipping point, but one that could be spotted using the tools of epidemiology, when a particular idea reached a critical mass, rather than one that changed as a result of some new event or action. This does not diminish the point of what has happened this week, because financial markets can be critical in setting conditions for the real world. It is best, however, not to ascribe too many powers to the words of Powell or AMLO. Rather than the excitement in the stock market, where the reversals are still not enough to tell us that the trends of the last few months are over, try looking at the dollar. As I commented on Monday, it had been a mystery for a while that the dollar had stayed strong even as yield differentials compared to other countries narrowed as Treasuries rallied. It looks like this may have reached a point of unsupportable absurdity at about the same time that the Treasury market turned. (And the analysts at Bank of New York Mellon may well be right that this owes much to adjusting to perceived risks, rather than changing yields. But by adjusting to the political risks, a weakening dollar can reduce the pressure for everyone.) The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index has swiftly dropped through its 50-day moving average, and is approaching the important technical support of the 200-day moving average.  That makes life easier for U.S. exporters. It also makes life far easier for anyone trying to run an emerging-market economy. Emerging-market currencies have also ticked up in recent days, and Treasury yields have risen a bit from their absurdly low level of Monday afternoon, though remain at levels that make life a lot easier for all concerned. So rather than a spark from the Fed, I think in the last 24 hours we have seen one of those moments when investors collectively grasp that a few trades have been taken far too far, and they step back. That development is undeniably positive. Whether it presages a new and positive trend will rest on the efforts of the leaders of the U.S., China and Mexico to sort out their differences. Watching the news from the U.K., my home country seems ever more to be in the grip of an anachronism. And I am not referring to the sight of a U.S. president being greeted in a palace by a monarch and sundry princes, princesses, dukes and duchesses, nor yet the sight of the president examining a parade of guardsman in implausible fur-skin hats. No, the first story on the BBC news at lunchtime on Tuesday was not President Donald Trump's visit, but instead about the downfall of Neil Woodford. For non-Britons, Woodford is one of the most famous British fund managers of the last decade or so. He created an enormous stir five years ago when he left his old berth at Invesco Perpetual to set up his own new stable of funds. Now his new flagship is closed to redemptions following a mass of investors pulling money out of the fund. Money followed the star manager in the belief that he could outperform wherever he went, and abandoned him with indecent haste when he failed to deliver. This much was depressingly predictable. There is skill in investing, but it is very hard to identify, and past performance gives no clear evidence that the next few years will also see good performance. That said, I was genuinely surprised when I compared the performance of the Woodford Equity Income fund with the FTSE-250 index of U.K. mid-cap stocks, which seems the fairest benchmark. Compared to an index which was suffering from the uncertainties for British companies wrought by the Brexit debacle, Woodford's performance was not that bad. It is only in the last few month that it has starkly diverged to the south of the benchmark:  This is not the kind of performance that screams "star manager" in neon lights, but the Woodford style of making concentrated contrarian bets is bound to go through periods when it does badly. If his investors really gave up on him this quickly, they must have gone in with absurdly high expectations. Even if he had as much of a Midas touch as hoped, it was perfectly possible to sustain a bad period like this every so often. So this reflects as badly on the behavior of British investors and the guidance they had received as it does on the performance of Woodford's fund. Looking at the assets held in the fund, we can see that investors' patience did indeed run out very quickly, and that the steady decline of the last three years (most of it in line with the Brexit-stricken market) prompted ever more clients to jump ship:  All of this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. With a few exceptions, the best funds in the world of active equity management are also the smallest and nimblest. They log impressive numbers when they are small and a few big bets on some small and little-known companies can really move their needle. Once they grow big and unwieldy, outperformance becomes far harder, and the incentive to track the index grows much stronger. Get too big, and it grows almost impossible to maneuver without moving the market ahead of you. For the most famous example in American investing history, look to the Fidelity Magellan fund, once the vehicle for the swashbuckling Peter Lynch and the first ever mutual fund to exceed $100 billion in assets in 1999. Twenty years later, it has $16 billion. Expecting even a star manager operating within a positive culture to keep outperforming in all market conditions, and with far more assets to manage, never made much sense. Pouring money into Woodford's new venture, largely on the basis of his name, therefore made little sense. Having done so, it made even less sense for Britain's long-suffering small investors to pull their money out again so quickly, but that is what they have done. That brings me to another interesting victim of collateral damage in this episode. When I started covering the British fund management industry about 30 years ago, Hargreaves Lansdown was a spunky and aggressive independent financial broker. There were dozens like it, but it found a way to grow. Its business model may be best described for American readers as somewhere between Charles Schwab and Merrill Lynch — it offers a dealing platform that makes it easy to buy and sell, and also offers advice. It staunchly favors active management over passive managers. And, as can be seen from the following chart, its performance has been quite remarkable, with its share price far outstripping Charles Schwab's since 2007, even if currency effects are ruled out, and it has done this despite the handicap of a much more sluggish home market:  Hargreaves Lansdown has always been a huge backer of the Woodford funds, and listed the Woodford offerings in its "Wealth 50" list of its "favorite funds." Its customers held 31% of Woodford Equity Income, a damning statistic that seems to have convinced investors that the Hargreaves Lansdown business model is also in question. It fell 4.6% on Tuesday as the market rose. Writing this in an American market now dominated by passive exchange-traded funds and fee-charging advisers bidding to help investors with their asset allocation, this entire episode looks like a weird throwback. There are problems with the passive approach, but it only takes an incident like this to remind us that passive investing has grown so strong for a reason. In the U.S., people seem to have grasped about 20 years ago that piling money into active funds with recent hot performance, and expecting star managers to keep shining, were really bad ideas. They remain bad ideas in the U.K. But Americans are not totally immune as bonds retain the cult of the star manager. In 2014, the year when Woodford left Perpetual, Bill Gross shocked all by leaving Pacific Investment Management Co. That move also failed to work out. As for the U.K., where retail investors are still very poorly served by comparison with the options available in the U.S., we can at least hope that British investors never make that mistake again. The BBC — Bloomberg Book Club. There is one more day until we will hold a live blog on "Dear Chairman," Jeff Gramm's brilliant history of shareholder activism told through letters to company chairmen. It tells of the exploits of the likes of Ben Graham, Warren Buffett and Ross Perot as they worked out how to take on company boards and win. it is great fun. I hope those of you who have read it have enjoyed it. This will be the second edition of the Bloomberg book club, as we continue our experiment in how to cover books and build a community. All suggestions (ideally constructive) are welcome, including nominations for future books. Your chance to question Gramm directly will come on Thursday at 11 a.m. New York time. Just go to on the Bloomberg terminal. As well as the author, you will also hear from me and our head of breaking news, Madeleine Lim, who spends much of her life covering shareholder activism in real time. The terminal link is {TLIV 5CEFFC2E68900003}. You can contribute questions ahead of time on the IB chat room that we have set up on the terminal. If you don't have access to it, you can arrange it by sending an email to the address for the book club: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. If you are one of those unlucky souls who do not have a terminal, you can also send questions directly to that address via email. Please let us know what you think. And if you have problems, let me quote from the end of Gramm's acknowledgements: "As for my mistakes, inaccuracies, misjudgments, and general failures in duties of care and loyalty in the composition of this book … Well, I've assembled a seven-person board of directors and we have taken out a large directors and officers insurance policy. The board will be happy to meet with you once a year, in Nome, Alaska. Please limit yourself to one question."

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment