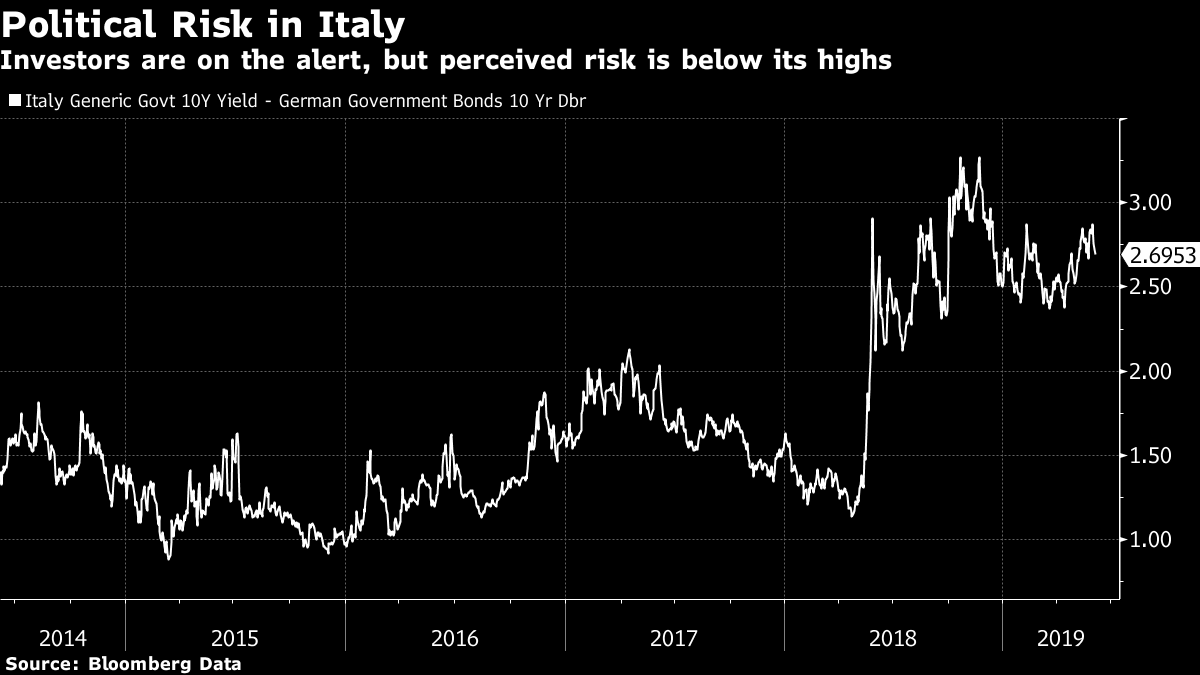

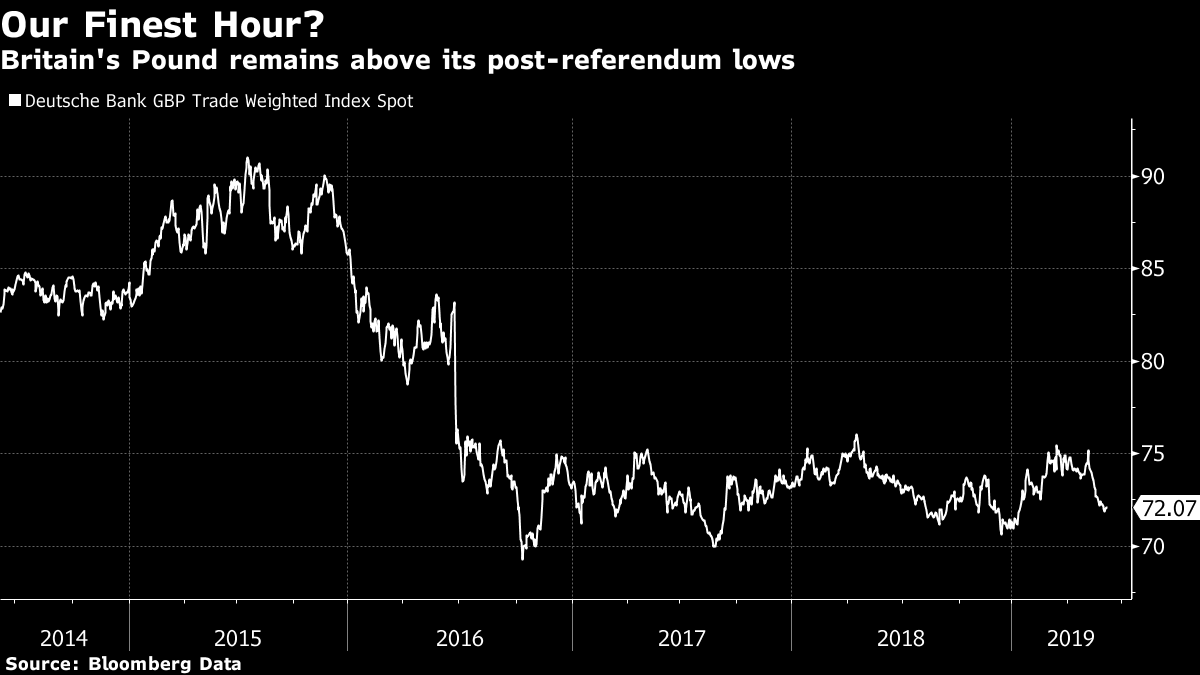

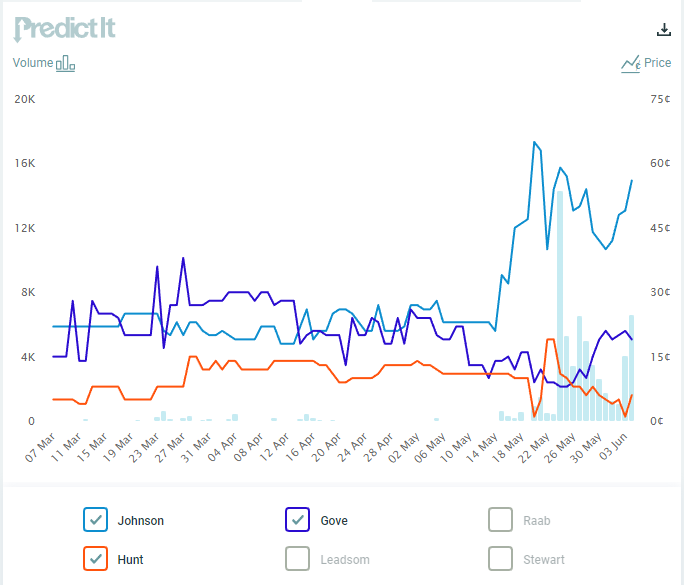

What's priced in? Risks abound in the world these days. From Italy to the U.K. and from Mexico to China, there are extreme concerns in financial markets over trade and international relations. The problem for investors is that it's not enough to predict whether a risk will come to fruition. They also need to work out whether such risk shave been priced into asset prices. If markets have done their job correctly, there is little money to be made by predicting the situation correctly. So, while not trying to go too far into exactly what might happen in the various conflagrations around the world, here come some estimates of what has been priced in. Italy. Italy's ruling coalition of left- and right-wing populists agree on little beyond their dislike of the European Union and their desire to spend more money. With neither side wishing to abandon the coalition just yet, this leaves them with little choice but to confront Brussels over Italy's bulging budget deficit. This dispute simmered to a boil last autumn as the Italians presented a budget that wasn't well received. It is boiling up again. What does the market think? Italian stocks fell precipitously after the coalition was formed a year ago. Since then, though, Italian stocks have traded roughly in line with the rest of the EU. At the moment, the market seems to think that the risks of a damaging confrontation are no greater than was apparent when the coalition was formed:  More important is the bond market, which has the ability to impose its own version of reality. If investors think Italy is a greater risk, that judgment will result in higher borrowing costs, putting Italy's leaders under greater pressure. The politicians watch the spread between German and Italian bond yields. Matteo Salvini, the deputy prime minister, has said that the spread can't exceed 4 percentage points. On that basis, the market is not helping Brussels in its attempt to bring Italy to heel:  Remarkably, on what was admittedly a topsy-turvy day for bond markets globally Wednesday, the spread actually tightened even as the risk of confrontation seemed to increase. The risk of a major crisis in Italy's relationship with the EU is, therefore, not seriously priced in at this point. There is plenty of downside for Italian assets if the confrontation escalates. Britain. Britain's parliamentary soap opera over Brexit is on hiatus for a few summer weeks while the majority Conservative Party tries to decide on a new leader. The trade-weighted value of the pound has fallen, showing that the market does not regard the contest to succeed Theresa May as prime minister as a positive development. But the pound still remains comfortably above a clearly defined lowest range for the post-referendum period. For all the political excitement of the last three years, sterling has traded in a remarkably tight band following the shocking devaluation it suffered on referendum night:  This suggests that the worst possible outcome is not being priced in. That, as far as markets are concerned (many British politicians and their voters would disagree) would be a "no-deal" exit on the date of Oct. 31, in which the U.K. suddenly left the many EU treaties which are currently part of U.K. law and started trading with its near neighbors in Europe on the minimal backstop terms prescribed by the World Trade Organization. Thus the pound still implies that the risk of a "no-deal" exit, rather than a more orderly but still damaging exit from the EU single market, is unlikely. There is reason to support this, as MPs in Parliament explicitly voted down such an option when given such a choice earlier this year. But it ignores the fact that several of the candidates to succeed May actively support such an outcome. The best known, Boris Johnson, appears very likely to win, if the prediction markets are to be believed. He seems to have a strong lead over his main competitors Michael Gove and Jeremy Hunt, both of whom favor going through with leaving the EU but appear far more reluctant to countenance leaving without a deal. This is how the odds on the contest to be the next British Conservative leader, and hence prime minister, have moved in the last three months, according to the PredictIt prediction market:  This leaves three options, all of which could be true. Either: - Investors think Johnson is lying and will not opt for no-deal when push comes to shove; or

- Investors are confident that Parliament can block him as prime minister from making a no-deal exit; or

- The foreign exchange market is badly underestimating the risk of a no-deal exit.

Take your pick, but it seems that the current balance of British risks is not adequately priced. Mexico. The tweet by President Donald Trump announcing tariffs on Mexico in retaliation for its failure to stop Central American migrants crossing the border into the U.S. was a genuinely shocking development. While the issue was known to be very important to Trump, this particular measure had not been floated publicly before he announced it. It seems best to assume that the market thinks it is not going to happen. There were shocked reactions in the value of Mexican assets after Trump was elected in 2016, and again late last year when then president-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador announced that he was canceling a new airport for Mexico City. That was taken as a declaration of war against international investors. Once in office, AMLO has proved to be more pragmatic than expected. But the main measures of pressure on Mexico, the performance of its equities compared to the rest of the world and the spread of its bond yields over equivalent U.S. Treasury yields, both suggest that he has been given little credit and that investors think the risks of an all-out trade war are adequately priced for now:  Of course, tariffs would not merely affect Mexico. Trade between the U.S. and its southern neighbor is largely about building cars and their components. The same car can cross the border several times during the process of construction as plants in both the U.S. and Mexico contribute. These carefully calibrated production chains would be broken if tariffs needed to be paid every time the border was crossed. It could be a disaster for the U.S. car and component manufactures. This is how the S&P index for the sector has fared compared to the S&P 500 since the beginning of 2011:  Two key points emerge: - Investors have long regarded the U.S. auto-manufacturing industry as utterly stricken, and

- The announcement of tariffs last week has done nothing to change that.

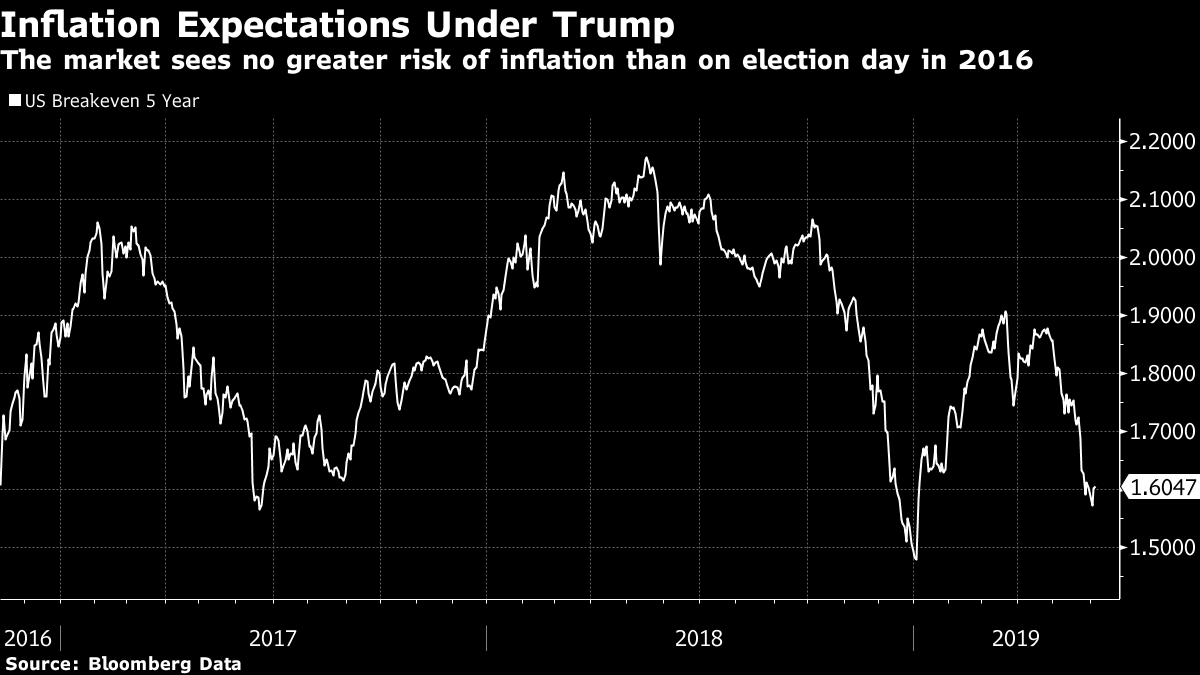

After such a terrible run, maybe this is understandable. But on any sensible assessment, tariffs would make a bad situation far worse. The emollient language coming from Mexico's new leadership may have helped to sway sentiment in the markets. The increasingly strong resistance from Republican legislators in the U.S. also increases the chances that the tariffs will not be imposed on schedule. But ultimately the only opinion that counts is Trump's, and the chance that Mexico can do anything in the near future to stem the tide of immigrants is zero. The risk of tariffs being imposed that the market is currently pricing is also zero. It needs to be a little higher. China. The question with China is what risk to price into its markets. For the U.S., the conflict is generally presented as a righting of historic wrongs, after China replaced many U.S. working-class jobs. In China, it tends to be seen as a battle over whether the country will be allowed to develop in the future. For a startling account of Chinese perception, read this piece by my old friend and mentor Martin Wolf in which he refers to a "looming 100-year conflict." The U.S. view of the conflict also stretches beyond trade. Neither side has much chance for compromise. Markets are gradually coming alive to the risk that the conflict of China will stretch far beyond tariffs, and will be harder to resolve than a trade dispute. As economists from BNP Paribas said in a briefing in New York on Wednesday, markets are starting to wake up to the new perception in Washington that China is the single most important national security threat to the U.S. They figure there is 50% possibility of a truce and further discussion, but that a trade deal with China really doesn't matter. That's because if a trade deal does get signed, there are enough irritants and friction in the broader U.S.-China relationship to break the "spirit of a deal," according to Daniel Ahn, the chief U.S. economist at BNP. Sentiment in China is that the U.S. is trying to contain Chinese technologies such as artificial intelligence and 5G. This gives BNP the view that this is not just a trade war, but a technology war. That is a pity, because overall BNP believes the economic impact of tariffs should be manageable and not enough to tip the U.S. into a recession. All the tariffs announced are expected to shave U.S. output by only about 10 basis points. If there is a further escalation, that may shave an additional 30 basis points off GDP. But BNP believes the bigger impact will be on inflation. They estimate a rise of about 0.3 to 0.5 percentage points in headline CPI if there is further escalation, meaning that the people who will be affected are the consumers, not China. That is significant because it would upend the widespread assumption that interest rate cuts from the Federal Reserve are in the offing. The recent drop in bond yields has gone a long way to trying to price in some of the risk of a general slowdown, but it is worrying that inflation expectations are falling despite the real risk of rising tariffs. Indeed, the bond market is not pricing any greater risk of inflation over the next five years than it was pricing on election day in 2016:  Because of these tensions, BNP has revised its global outlook to "relatively subpar growth" for most advanced economies. While its base case is still not a recession — although they do put a 25% probability on recession, which is uncomfortably high — the firm's economists think that trade and other concerns will weigh on business investment. That seems a sensible judgment. China and its economy and its seemingly intractable conflict with the U.S. have preoccupied investors for years now. The broader ramifications of their dispute, and the effect that tariffs could yet have on the internal dynamics of the U.S. economy, are arguably still not fully priced in. With the assistance of Shelly Hagan. Book Club: A final reminder. I hope you have enjoyed reading "Dear Chairman," Jeff Gramm's brilliant history of shareholder activism told through letters to company chairmen. It tells of the exploits of the likes of Ben Graham, Warren Buffett and Ross Perot as they worked out how to take on company boards and win. It is great fun. Now the time has come to discuss it, along with any other issues concerning corporate governance and control that might interest you. This will be the second edition of the Bloomberg book club, as we continue our experiment in how to cover books and build a community. All suggestions (ideally constructive) are welcome, including nominations for future books. Your chance to question Gramm directly will come on Thursday at 11 a.m. New York time. Just go to on the Bloomberg terminal. As well as the author, you will also hear from me and our head of breaking news, Madeleine Lim, who spends much of her life covering shareholder activism in real time. The terminal link is {TLIV 5CEFFC2E68900003}. You can contribute questions ahead of time on the IB chat room that we have set up on the terminal. If you don't have access to it, you can arrange it by sending an email to the address for the book club: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. If you are one of those unlucky souls who do not have a terminal, you can also send questions directly to that address via email. We all have busy schedules, but I hope you can find the time to join us to stand back a little from the day-to-day noise and discuss a fascinating book.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment