Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that wonders if investors betting on a patient Fed to be proactive also think that oil and water also mix. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter

Debt Denies Risk-Asset Resilience

Sovereign debt is the Debbie Downer of financial markets.

Investors are wrestling with mixed U.S. data, underwhelming global growth, and an escalating trade war. While other asset classes have telegraphed optimism, sovereign debt is signaling a degree of caution, if not abject fear, about what comes next.

While U.S. stocks are barely down on the week through Thursday after collapsing on Monday, Treasury yields are decisively lower. Bund yields are solidly sub-zero. Chinese sovereign debt is being heralded as a clear winner in the clash over cross-border commerce.

And why wouldn't investors be smitten with the safest IOUs around? In virtually every corner of the globe, economic activity is surprising to the downside.

Inflation is too. And investors have given up on the prospect of escalating price pressures. In the case of Europe, Bank of America's survey of investors found that "many respondents believe the ECB doesn't have the tools to lift inflation & some now see inflation as beyond'' the European Central Bank's control.

To be fair, in the case of U.S. debt, there's an extenuating circumstance contributing to this week's decline in yields: convexity hedging 2.0 on the part of holders of mortgage-backed securities.

Another note of caution for Treasury bulls betting on an extension of the rally: expectations that the Federal Reserve is poised to ease – and perhaps materially – by the end of 2020 has helped juice the rally in longer-term debt. But patience – the central bank's mantra – is almost definitionally incompatible with a proactively accommodative posture.

Even Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari – arguably the most dovish member of the FOMC – does not think a so-called "insurance" rate cut is appropriate. A more hawkish member – Kansas City chief Esther George – thinks a rate reduction could fuel financial excesses.

If the market switched to betting the Fed will stay on hold this year, and if 10-year yields moved in lock-step with fed funds futures, then 10-year Treasuries would be north of 2.60% and trading closer to the 2019 highs than the trough.

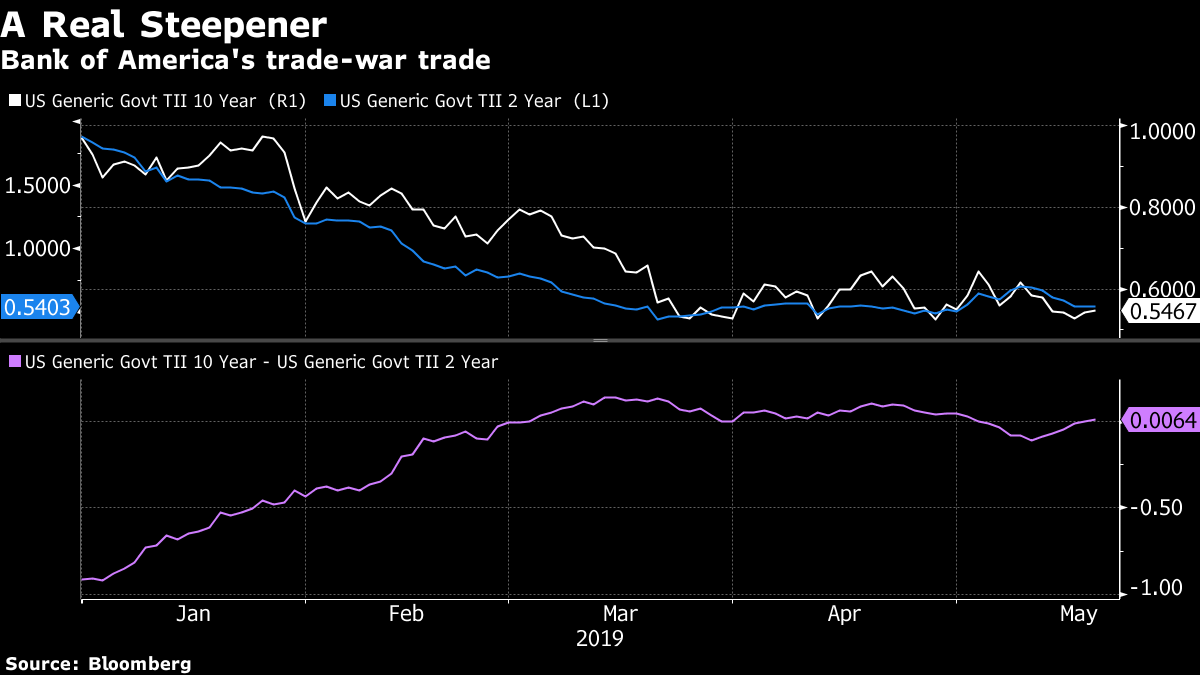

For now, Bank of America sees a clear trade-war trade in the bond market: a steeper real 2s10s Treasury curve.

"On a happy conclusion to trade negotiations, real 2s10s should at least track nominal 2s10s steeper (real 2s10s is currently inverted, after all)," writes Mark Capleton. "On abandoned talks, full coverage tariffs that look likely to stick would lift 2y inflation and this, coupled with expected Fed cuts, should slash 2y real rates, steepening real 2s10s sharply."

An Open Window Leaves No Pain

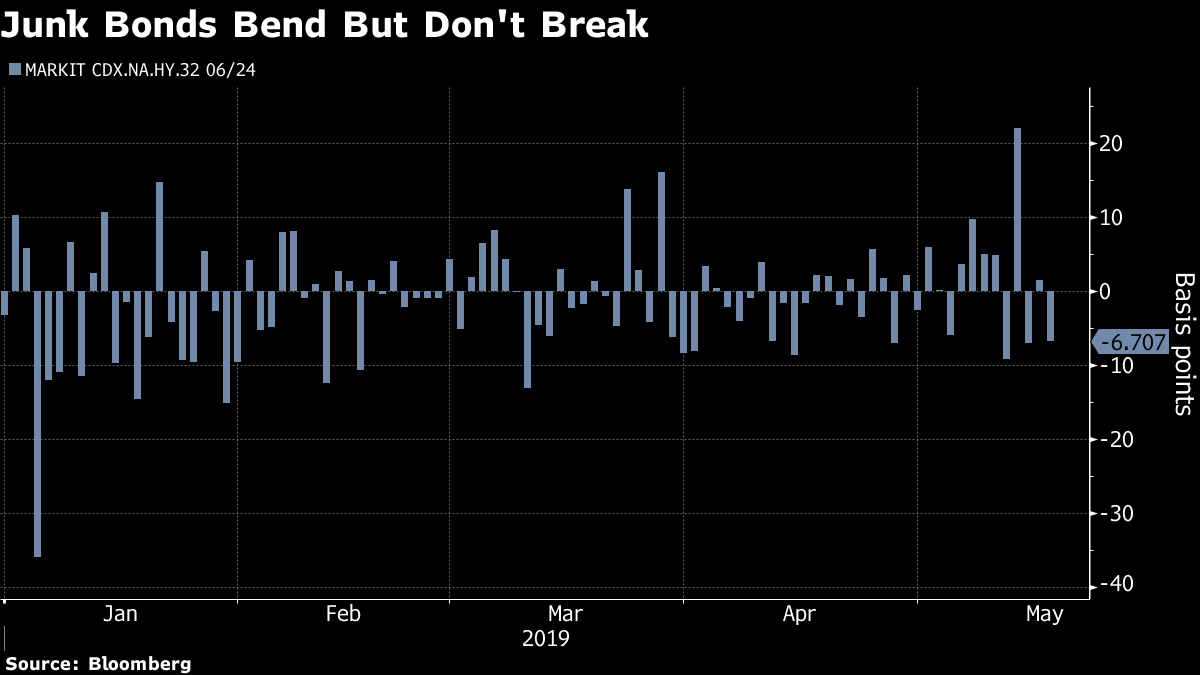

Wall Street was betting that junk bonds would be the next casualty of the trade war. Well, high yield bent, but it hasn't broken.

The riskiest U.S. debt kicked off the week with the biggest jump in credit default spreads in more than a year. On Wednesday, even as U.S. stocks rallied, HY CDX widened yet again – suggesting that the renewed move to risk-on wasn't being confirmed.

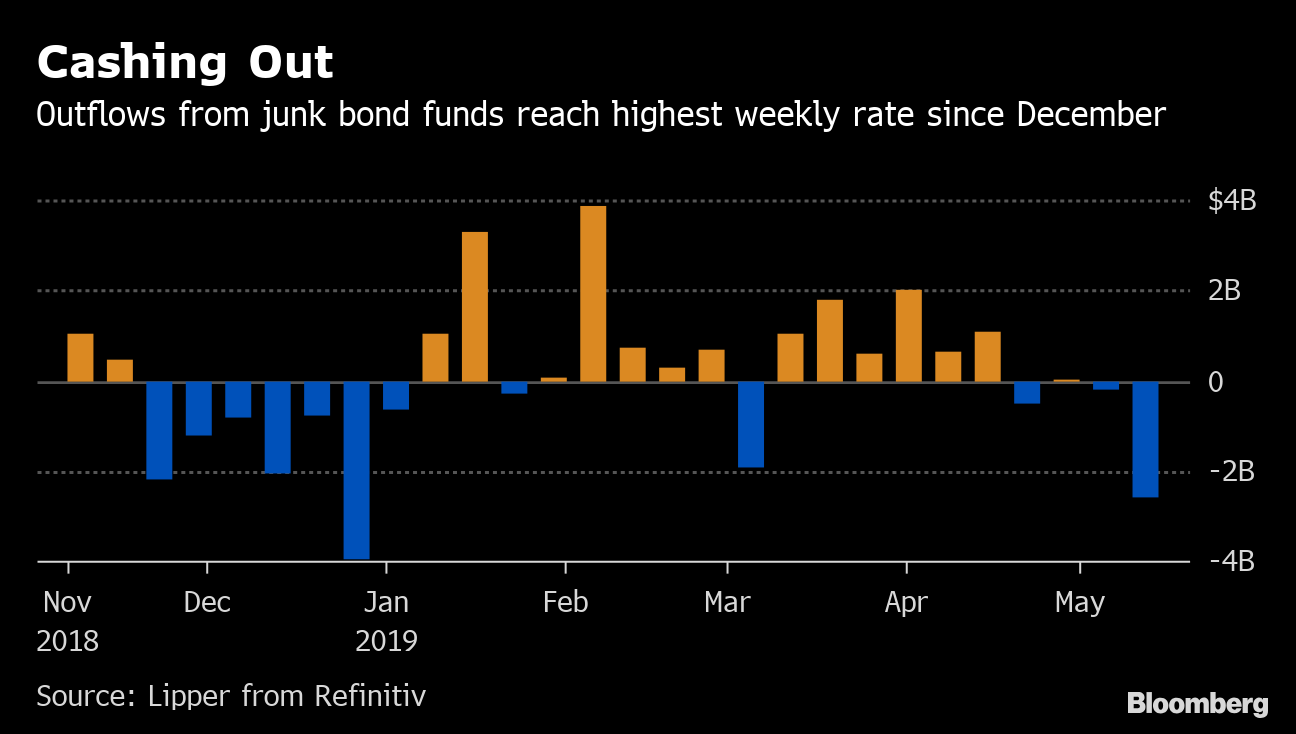

The junk space is suffering its biggest outflow since December, and investors are the most bearish on credit since 2012, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Yet by Thursday, high-yield spreads joined the risk rally, managing to retrace about half of their weekly move.

U.S. junk debt remains a worse performer even than emerging-market dollar bonds since the trade war re-reared its head. There's a school of thought that this is warranted, in part because some of the high-profile companies that had IPOs recently haven't produced awe-inspiring results, to put it mildly.

But the first-order effect of those equity raisings actually bolsters the outlook for bondholders. And to boot, the retreat in borrowing costs has spurred a bout of issuance that is specifically designed to reduce near-term vulnerabilities. "Refinancing" has been listed as a use of proceeds for more than 70% of high yield debt that's come to market this year. When the Fed opens a dovish door, it opens a window for the marginal borrower in Corporate America. A wide-open window means no imminent default pain.

Post a Comment