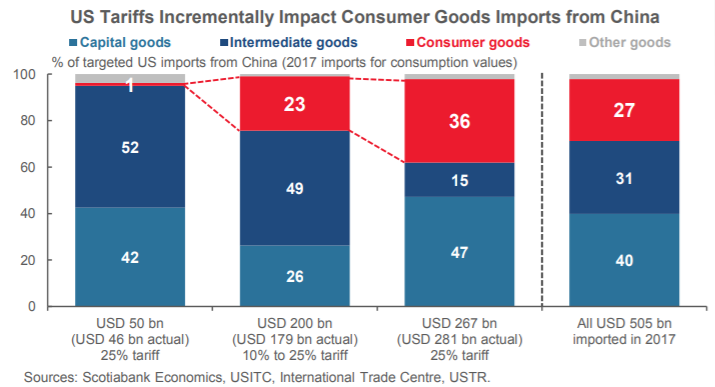

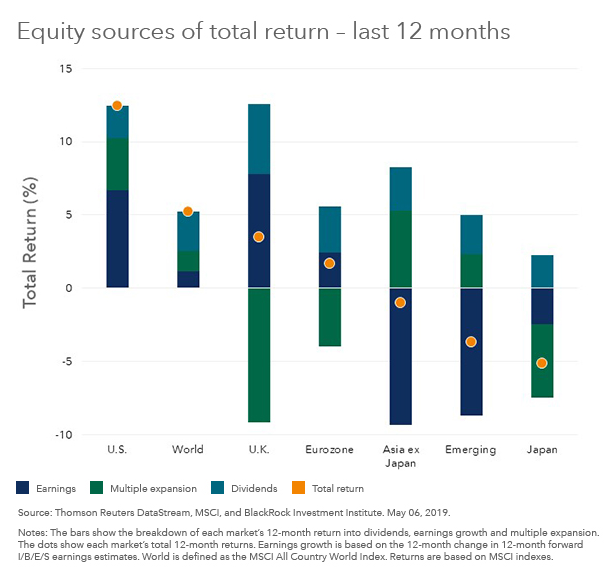

| Last week saw a breakdown in U.S.-China communications. But can it be repaired? The capital markets, at any rate, seem to be betting that way. A week ago, few believed that the U.S. would go through its threats to impose new tariffs on Chinese goods. It happened anyway. The weekend has brought further intensification of the rhetoric, yet the reaction has been surprisingly muted. U.S. stocks entered this week priced for perfection. A week later, with the S&P 500 having fallen only 2.2 percent, they are still priced for something almost perfect. I would suggest there are two factors at work here. First, investors may be predicting, on the basis of the game theory everyone has been studying in recent weeks, that there will still be a painless resolution — that this past week's events were merely a communication breakdown that can soon be resolved. Second, they may believe that tariffs aren't that bad — or at least that they won't have too serious an effect on corporate earnings. The communication breakdown narrative goes as follows. Investors, like the media, had suffered a breakdown with the U.S. leadership, while China and the U.S. had also misunderstood each other. This was avoidable. This point from Marc Chandler of Bannockburn Global Forex puts the position in great historical context. Rather than simply take the U.S. framing, as investors and the media accepted at face value U.S. nearly daily claims that progress was being made, it behooves us to find a larger perspective. The fact of the matter is that in these negotiations, nothing is agreed until everything is agreed. That means that using the time-tested tactic like the Gulf of Tonkin incident, American medical students in Grenada, weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and the sinking of the Maine, the U.S. found a pretext to do what it wanted. At first, many investors appeared dazed and confused. But later, in the evening on Friday, they appear to have convinced themselves, yet again, that all will be well. The song remains the same: "This is all just posturing, a publicity-hungry American on one hand and a bunch of hide-bound bureaucrats on the other. In the end all will be well, because both sides know that it is in their interests to reach a deal." And thus, somehow or other, the markets ramble on. The S&P 500 managed to gain slightly on Friday, following what once would have been shocking news that higher tariffs had been imposed. Does this make sense? Too much analysis has focused on the U.S. side of the equation. As Andrew Browne pointed out for Bloomberg Opinion, Chinese domestic politics make any deal hard to reach, and limit the effectiveness of slapping on tariffs. Further, as Jamil Anderlini pointed out in the Financial Times, the Chinese authorities may have misunderstood the Americans' incentives and aims. Having seen the president tweet at his central bank imploring them to take desperation measures to stimulate the economy, China assumed that he must be desperate and in a weak negotiating position. That was wrong. To that extent, China has nobody to blame but itself. Personally, I am not sure that Jonathan Bernstein of Bloomberg Opinion is right when he says that Trump's tariffs are "terrible politics." Rather, just as when Trump is singing his immigrant song, his policy on the issue plays brilliantly to his base — and critically to exactly the part of his electoral coalition from 2016 that the Democrats most need to prise away. Stepping up the dispute now should keep it alive as an issue in next year's election. This need not be bad politics at all; indeed, here is a growing American consensus in favor of growing more aggressive with China. To quote Chandler of Bannockburn Global Forex again: The question is why did President Trump conclude that it was in his interest not to reach an agreement. As in most important decisions, it is over-determined (the opposite of mono-causal). First, it became clear that a comprehensive understanding that went far beyond trade was unlikely. It had been oversold. Second, like the recent overtures to Democrat leaders Pelosi and Schumer on infrastructure initiative, being hard on China is one of the apparently few areas of bipartisan agreement. In fact, shortly after Trump's tweets on May 5 declaring the end of the tariff truce, Schumer sent an encouraging and supportive tweet. A further point is that this is not an issue with binary outcomes. China and the U.S. will be loggerheads for decades to come. China's economy will likely grow to be bigger than that of the U.S., but this is not inevitable. This need not be an intractable international dispute like the ongoing confrontation between India and Pakistan over Kashmir. But the chances are that it will drag on for many years, with occasional conflagrations like this one. So the question moves to the issue of whether these tariffs really matter. To be clear, nobody should doubt that U.S.-Chinese relations matter, a lot. But do these tariffs matter all that much? Trump has some surprising support for the notion that his trade policy so far has done little damage — from Paul Krugman, the economist and liberal columnist for the New York Times, who won a Nobel prize for his work on international trade. He argues as follows in his most recent New York Times column: In the short run, a tariff is a tax. Period. The macroeconomic consequences of a tariff should therefore be seen as comparable to the macroeconomic consequences of any tax increase. True, this tax increase is more regressive than, say, a tax on high incomes, or a wealth tax. This means that it falls on people who will be forced to cut their spending, and is therefore likely to have a bigger negative bang per buck than the positive bang for buck from the 2017 tax cut. But we're still talking, at least so far, about a tax hike that is only a fraction of a percent of GDP. He goes on to say that it is hard to say that this trade war, so far, could cause a global recession. To be clear, he spends most of his column stressing that trade is about politics and that the long-term consequences of the current U.S. policy, in conjunction with its other foreign policies, could be to make the world a much more dangerous place. But for the short term, even this unexpected escalation does not have that great an impact on the economy, or on companies' balance sheets. That is a fair point. The trade war talk has had such limited impact over the last year because there is a limit to the number of companies that will predictably suffer a decline in earnings as a result. Also, as some interesting research from Scotiabank points out, the choice of goods to be hit by tariffs has been carefully calibrated to have the least visible effect possible on U.S. consumers":  The first wave of tariffs, shown in the first column, were close to invisible to the consumer. The latest wave, in the second column, would still have a more limited impact. A further escalation, as threatened by the president this week, would have a far greater impact, and that impact would be felt by some of the big companies currently keeping the stock market near record levels. That said, the politics of imposing them would be very difficult. To quote Scotiabank: Today's tariff increase and the possible further 25% tariffs on the remaining third list of goods would cause much more obvious and immediate pain for average American households — including the White House's political base — than the three rounds of tariffs imposed in 2018. A 25% increase in the prices of smartphones, tablets and computers heading into the 2020 vote has never struck us as a winning electoral strategy. This suggests there's a good chance the next wave will never come. That said, the effect of the second round of tariffs just announced could be made worse by the fact that many importers had deliberately "front-loaded" orders, ordering product before it fell subject to a tariff. The upshot is that the negative impact on trade so far has been masked, and there's room for a particularly sharp fall from here. To illustrate this possibility, look at this chart from George Saravelos of Deutsche Bank, who cautions that the market has been complacent:  So it remains a reasonable position to doubt that the tariffs so far are actually that important — but to believe that adding more from here could be politically difficult for Trump, and could have a stronger impact on both the economy and the stock market. Taken together, we have an explanation for the markets' relative calm. These tariffs in themselves are still not that severe, while the arguments to reach an agreement without further escalation remain strong. The development was worse than expected, but there is little need to sell stocks further. (For the sake of the trade deal — there are plenty of other reasons why investors might think that U.S. stocks were now too expensive.) What then, are the chances for a deal, and what should investors do about it? It is hard to argue for a lot of upside from the current situation. A truly definitive resolution to the tensions between the world's two largest economies is not going to happen. The greatest reason to expect a downside comes from the incentives facing Trump. At present he has an exciting case to bring to the electorate next year — the stock market is strong, and unemployment stays low. It would take an economic decline clearly caused by tariffs (which is unlikely this side of the election) or a market downturn to dissuade him. That leads us to the ultimate problem of market reflexivity. Markets do not merely reflect reality; they often change it. The calm market reaction this week will bolster the nerve of the U.S. negotiators to play it tough. If investors want to change Trump's mind, they need to sell — even though there's no pressing need to. As Ethan Harris of BofA Merrill Lynch put it: "no pain, no deal." Without the pain of a market selloff, Trump is better off keeping the issue alive and making a popular push against China. That does mean there is a risk, as Harris says: Could there be an accident where both sides miscalculate and stumble into a protracted war even though it is in neither side's interest? We still see this as very much a tail risk as the market and political costs will escalate dramatically in a full-blown war that extends to all Chinese products, including many consumer products. Wars are popular during the departure parades, but not when the casualties mount. So for now we assume the escalation has a relatively small impact on the medium term outlook. It adds to the case for weak capital spending, but does not alter our global "soft landing" scenario. The risk is that markets take time to create enough pain and some persistent damage is made to the global economy. The subsequent upside would then be smaller. Meanwhile the next few weeks could be rocky. It is only when the levee breaks, and all hell is let loose on markets, that the parties will be forced to come to an agreement. For the foreseeable future, caution is in order. What the U.S. has that the rest of the world doesn't. Throughout the post-crisis era, the U.S. stock market has trounced the rest, despite the fact that the crisis itself stemmed from the United States. It was not a development that many had expected, and yet it has continued almost uninterrupted for a decade. The "buy American" trend has been renewed in full force in the last 12 months. The following chart, from Russ Kosterich's blog for BlackRock, handily breaks down the sources of U.S. outperformance into earnings, dividends and changes in the price/earnings multiple:  In essence, all of these sources of return have been working in favor of the U.S. The rest of the developed world has been hampered by multiple contractions (especially the U.K., where the Brexit imbroglio has undermined confidence), while the emerging world was pulled back by declining earnings. In the longer term, Koesterich suggests that U.S. outperformance rests in critical outperformance by U.S. companies themselves. They have grown more profitable. He says: During the "aughts" decade, the average spread in profitability, measured by the return-on equity (ROE) between the S&P 500 Index and the MSCI ACWI-ex-U.S. Index, was roughly 1.5%. Not only was the spread relatively narrow, but those years witnessed a prolonged period, leading up to and including the financial crisis, when profitability was higher outside of the United States. Things have changed post-crisis. Since the beginning of 2010 the average ROE spread between the two indexes has widened to 3.7%. Just as important, since the start of the decade, there has not been a single month when U.S. corporate profitability was below the ROW. Put differently, not only have U.S. companies been significantly more profitable than their non-U.S. counterparts, but excess U.S. profitability has been consistently more reliable in the post-crisis environment. Something about the crisis, then, rendered U.S. companies far better at driving a return from their equity. That, Koesterich goes on to suggest, is based in the U.S. success in finding macroeconomic growth — something that has eluded Europe and Japan: "Faster growth supports higher operating leverage." The other reason he offers is a familiar one. To an unprecedented extent, the biggest companies of the moment, when measured by market cap, are all from the same industrial sector and the same country. The companies that have dominated the internet are also dominating the stock market, and none of them come from Europe or Japan. (Tencent, Alibaba and Baidu do show that such companies can also flourish in China.) Stock market dominance for these companies is largely based on their superior profitability, again as Koesterich elaborates: The top three companies in the S&P 500 are Microsoft, Apple and Amazon. Their average ROE is 39%. By contrast, the top three companies in Europe — Total, SAP and LVMH — have an average ROE of 14%. Perhaps it's not such a mystery why U.S. companies, despite materially higher valuations, continue to outperform. These points are well made. They also suggest the factors that might end U.S. outperformance. Expanding multiples over the last 12 months show that there is confidence that earnings can continue to grow, particularly for the big companies that dominate the market. If anything happens to cast those growing profits into doubt, the U.S. market will swiftly look overextended. The political campaign for next year's U.S. presidential election is still taking shape. But there are some progressive ideas in the atmosphere. Any serious signs that the next president will take antitrust policy seriously, or attempt to break up the biggest internet players (as proposed last week by one of Facebook's co-founders), could end American outperformance.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment