| One thing you can do is buy a bunch of stock in some small publicly traded company and then put out a fake press release saying that Walmart Inc. is going to acquire that company. The stock will go up and you can sell your stock at a profit. Later Walmart and the company will deny it and the stock will go back down, but if you're quick you can make a profit. Even later, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and federal prosecutors will come after you, but if you cover your tracks well and live in a foreign country you might be okay. Anyway this is very much a thing that people do occasionally in the U.S. stock market. Another thing you can do is buy a bunch of some cryptocurrency and then put out a fake press release saying that Walmart is going to "partner with" that cryptocurrency: Walmart Inc. said it hasn't agreed to partner with Litecoin, refuting a statement earlier Monday that sent the cryptocurrency soaring. The statement released by GlobeNewswire isn't authentic, a Walmart representative confirmed to Bloomberg News. The company is in the process of trying to learn more about the release. The Litecoin Foundation said in a tweet that it hadn't entered a partnership with Walmart. At 9:30 a.m. in New York, GlobeNewswire issued a statement saying that the world's largest retailer had agreed to partner with Litecoin and accept the cryptocurrency as payment. Litecoin had soared as much as 33% on the announcement, with other cryptocurrencies gaining as well. Litecoin erased almost all of its gain, rising less than 1% at 12:12 p.m. in New York. Walmart shares fell less than 1% to $145.01 after earlier trading in positive territory. A spokesperson for Intrado, which operates GlobeNewswire, said the company is removing the release from its website and is investigating the incident. Intrado distributes 200,000 press releases per year, according to its website.

This is probably better than the corporate version, for all the reasons that crypto is generally attractive for crime. You can trade your Litecoin anonymously, without going through a broker who will rat you out to the SEC. You can trade your Litecoin any time; you don't have to wait for the markets to open to put out your press release. Also this will just work really well: "Walmart buys small company" is news, for the small company, but not that many people will care; "Walmart does crypto thing" is going to get more attention, so people will definitely read your fake news and the price of Litecoin will go up. Also, in the corporate version, both Walmart and the fake target company will deny the story. In the crypto version, Walmart will probably be confused, and it's not even clear what it would mean for a cryptocurrency to deny a statement. A cryptocurrency is decentralized, etc.; there is not necessarily anyone who makes decisions for it and can say "this is fake." Though in this particular case there is someone who controls the @litecoin Twitter account and confirmed the fake press release, ahahahaha: A significant spike in Litecoin followed quickly-debunked headlines that Walmart Inc., the world's largest retailer, had agreed to accept the cryptocurrency as a payment mechanism at its stores. Litecoin's own verified Twitter account posted a link to the press release in a tweet that was later deleted. Charlie Lee, creator of Litecoin and managing director of the Litecoin Foundation, described the tweet and press release as an "unfortunate situation" in an interview with Bloomberg News. "The @litecoin handle, we have three people who control that and one of the people this morning, before I woke up, saw the GlobeNewswire [press release] and saw Yahoo News posting it and CNBC posting it and he thought it was true because he didn't know better," Lee said. "Pretty soon after that he realized he had made a mistake, that it was fake and he deleted it."

I love it. If you run social media at Amalgamated Widgets and you see a press release on the news saying "Walmart has bought Amalgamated Widgets," you are going to ask your boss "is this true" before tweeting about it; that's the sort of thing you might expect to hear from your own company. If you run social media for Litecoin just wave it all in, who knows, what does truth even mean. Good times, good times. One assumes that this is illegal — surely it's wire fraud? — and that U.S. authorities will be looking for whoever did it; this is just too fun a fraud not to prosecute. I do wonder if the SEC will go after this person (if they can find them) for securities fraud.[1] It's not really securities fraud; Litecoin is not a security. But Walmart is, and its stock moved on the news. If you accidentally manipulated Walmart's stock as part of your cunning plan to manipulate Litecoin, that might be enough for the SEC. I have said before that there are two basic theories of environmental, social and governance investing. One says "we will avoid investing in companies that do bad things, which will drive up their cost of capital, which will lead to a reduction in the number of bad things in the world." This has the advantage of (purportedly) doing good in the world: There is some mechanism by which your investing choices reduce pollution, solve climate change, etc. It has the disadvantage of foregoing returns: If you are raising the cost of capital of bad things, that means that the bad things have a higher return, and someone else is getting that return. The other theory says "we will avoid companies that do bad things, because doing bad things is unsustainable, and eventually the companies that do bad things will all go bankrupt." This has the advantage of promising higher returns: If you choose stocks that will go up, and avoid the stocks that go bankrupt, that's good for your investors. It makes no particular do-gooder claims, though. You're not making any claims about changing the world; you are just trying to make money from your prediction about how the world will change anyway. A third theory would be "we will invest in companies that do bad things[2] and turn them into companies that do good things, because (1) that is good and (2) doing bad things is unsustainable and eventually companies that continue to do bad things will go bankrupt." This has the advantage of promising higher returns (through stop-doing-bad-things activism) and of doing good in the world. It is a nice synergy of the two approaches; you are claiming both to have a direct positive impact on the world and to outperform the market. This third theory is, I think, hard for the average ESG fund to pull off. If you are buying 0.1% of a handful of companies you can call them up and say "stop polluting," but they will ignore you. But some people can pull it off. BlackRock Inc. clearly has more or less this theory: It buys huge stakes in every company, including coal companies and gun companies and all the rest, and then it sends them strongly worded letters asking them to be more sustainable, to pollute less or focus more on gun safety or whatever. Because it is a huge shareholder, it is possible that the companies might listen. (Because it can't really sell its shares, it is possible that they might not.) But really the way to implement this theory is through shareholder activism: You buy stock in oil companies, you yell at them to pollute less, and if they refuse you run a proxy fight to throw out their directors and replace them with new, more environmentally conscious directors. This roughly describes what tiny ESG-ish activist fund Engine No. 1 LLC did to Exxon Mobil Corp. this spring, and Engine No. 1 has dined out on it ever since. Here is a Bloomberg article from yesterday titled "Engine No. 1 Unveils ESG Framework to Scrutinize Investments": In a 38-page report released on Monday, the money manager said it would integrate ESG data with conventional financial analysis to scrutinize companies and pick investments. The "total value framework" seeks to predict how performance on ESG concerns affects a company's value. "ESG data is as core to the investment process as financially driven analysis," Chris James, founder of San Francisco-based Engine No. 1, said in a statement. "This framework, when applied to capital allocation, brings common sense back to capitalism itself."

Why not. Here's the report, titled "A New Way of Seeing Value: Introducing the Engine No. 1 Total Value Framework," which seems to mostly espouse the second theory of ESG ("if we buy stocks with good ESG scores they will go up") rather than the third, more interesting theory ("let's buy polluters and do activism") pioneered by Engine No. 1: True integration of ESG into fundamental analysis requires a bottom-up process in which environmental, social, and governance issues are integrated into financial-model forecasts. This means ESG data would not be held as a distinct factor, but would instead be used in assessing such line items as revenue, operating margins, and risk that ultimately drive the numerator of intrinsic valuation and the expected return. ESG factors are financially material because they can affect top-line growth, costs and margins, regulatory and legal interventions, employee productivity, and investment and asset optimization. … Our initial analysis strongly supports a far more consistent and powerful association than that found via traditional ESG data. It shows that the difference between a firm's Total Value and its shareholder value, and changes in those net externalities relative to industry peers, are strongly indicative of future changes in financial outcomes. Between 2010 and 2019, for example, the ten S&P 500 firms with the largest negative impacts, as ranked in 2019 ("Top Ranked by TV Impacts"), substantially underperformed the market; the ten companies with the smallest negative impacts ("Bottom Ranked by TV Impacts"), meanwhile, significantly outperformed (see Figure 10).

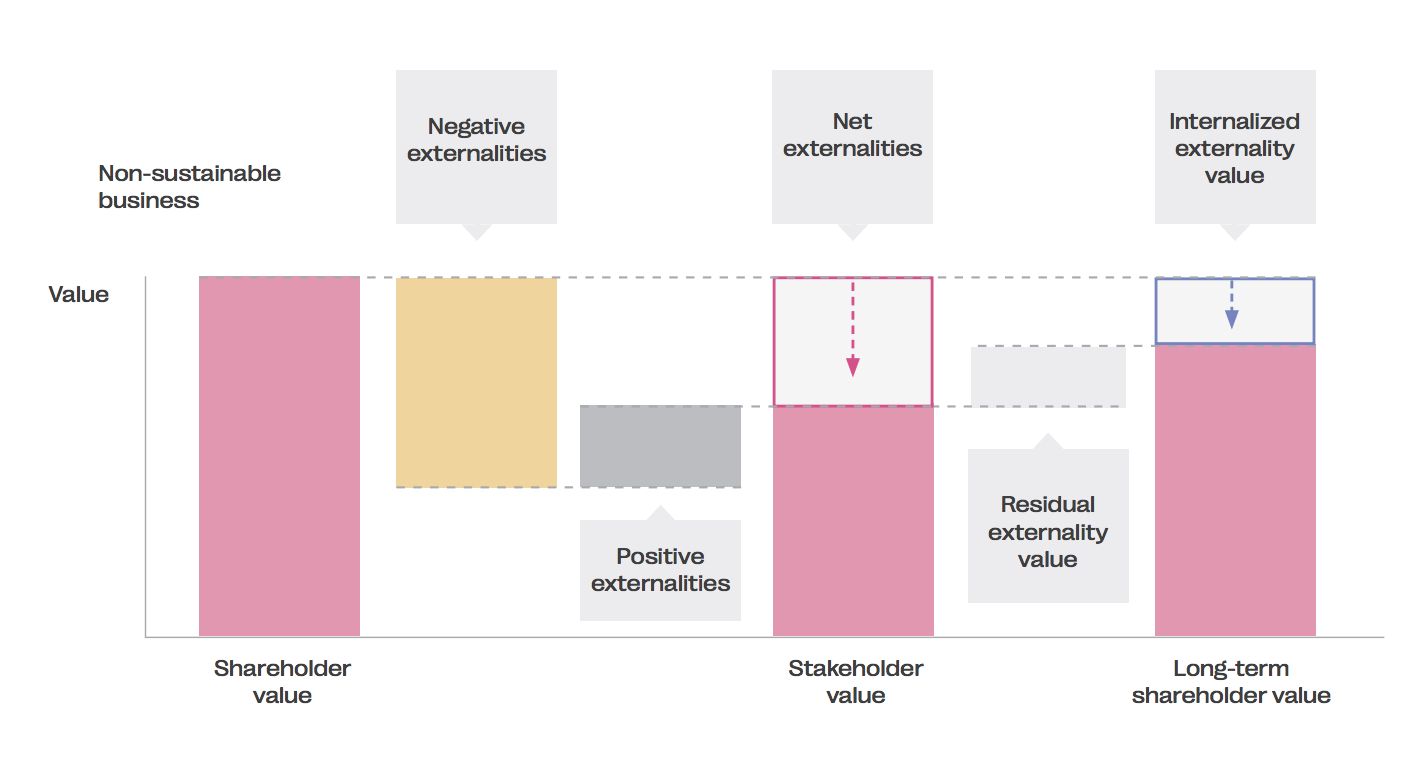

But I like the framework in this chart from the report:  The idea here is that a company makes money for shareholders (the first pink bar), does some good for the world (positive externalities, the dark gray bar), and also does some bad for the world (negative externalities, the yellow bar). The total value created by the company ("stakeholder value") is the sum of the first two things — shareholder value plus doing good for the world — minus the bad that the company does for the world. Over the long run, the world will notice, rules and norms and consumer behavior will evolve, and the company will have to internalize some of its (negative) externalities: Companies that pollute will have to pay carbon taxes, companies that are racist will lose employees and customers, etc. In the long run, shareholder value approaches total societal value; a company that makes money for shareholders at the cost of doing bad for the world will not be able to do that forever. I don't know what the activism takeaway here is. It's not "internalize your externalities"; by the analysis here, that reduces shareholder value. You're not going to go to an oil company and say "you should pay a carbon tax." Perhaps it is "stop creating bad externalities," or perhaps "conduct your internal financial analyses as though you had to internalize your bad externalities, because eventually you will." There's another chart on the same page showing the same analysis for a "sustainable business," which means that the gray bar is bigger than the yellow bar, the company creates overall positive externalities, and the long-term shareholder value goes up. The activism takeaway there is clearer, though in a bit of a depressing way. You buy stock in a company that is sustainable, that creates a lot of value for the world, that makes people better off in ways that cost them nothing, and you tell it to start charging more. Gotta capture more of that value for shareholders. This sort of resists summarization, but today U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Chair[3] Gary Gensler has both prepared congressional testimony and an interview with Jen Wieczner at New York Magazine about what he's up to at the SEC. Not like "here's a particular thing that I'm passionate about and my plan for new rulemaking," but more like "here is everything I'm thinking about with one sentence on each thing." If I had to give a broad summary, I guess I would go with "more disclosure"? That is a boring summary; pretty much every speech and interview given by every SEC chair since the founding of the agency could probably be summarized that way. Nonetheless I think it's accurate. From the testimony: The security-based swaps market is not a large market compared to the fixed income and equity markets, but it was at the core of the 2008 financial crisis. More recently, total return swaps were at the heart of the failure of Archegos Capital Management, a family office. …. To allow the Commission and the public to see aggregate positions, Congress under Exchange Act Section 10B gave us authority to mandate disclosure for positions in security-based swaps and related securities. I've asked staff to think about potential rules for the Commission's consideration under this authority. As the collapse of Archegos showed, this may be an important reform to consider Today's investors are looking for consistent, comparable, and decision-useful disclosures around climate risk, human capital, and cybersecurity. I've asked staff to develop proposals for the Commission's consideration on these potential disclosures. … First, given the surge in special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), I have asked staff for recommendations about enhancing disclosures in these investments. … Further, we are working to enhance disclosures with regard to how Chinese companies issue securities in the U.S. Chinese companies conducting business in certain industries, such as internet and technology, are prohibited from selling their ownership stake to foreigners. … We've seen a growing number of funds market themselves as "green," "sustainable," "low-carbon," and so on. I've asked staff to consider ways to determine what information stands behind those claims and how we can ensure that the public has the information they need to understand their investment choices among these types of funds.

The SEC is so pleasing because it is simultaneously the U.S.'s most general-purpose regulatory agency, the one that can move fast and aggressively to address climate change and Chinese geopolitics and financial stability, but it is also the most single-tool regulatory agency, in that it addresses all of these issues by mandating more disclosure. Three more specific points. First, Gensler continues to be a skeptic of modern equity market structure. From his interview with Wieczner: The orders that we put in on a digital app by and large don't go to stock ex-changes like NASDAQ and NYSE. They go to wholesalers; some people just call it the "dark pools." And so a lot of our markets are not lit. We don't have that order competition that can drive efficiency in a market. There's somebody paying for the order flow. That's not necessarily the best flow for us. … Can I just say something? It's not "free." It's a misnomer. It is not free, and it costs everybody who goes on those platforms. Because the platform is doing multiple things: One, they're selling your order flow. Two, they're collecting data, and the person paying for the order flow is getting that data. There's an inherent conflict because your order — your buy or sell order — is not necessarily competing in the market. So it is anything but free.

I don't know! We've talked a bit around here about the notion of banning payment for order flow, but Gensler's personal preference seems to be to go further than I thought plausible and ban all sorts of "dark" trading, forcing everyone to trade on an exchange. I would not bet on that happening, nor do I think it's a good idea, but it keeps coming up. Second, Gensler really doesn't like crypto. From his testimony: Right now, large parts of the field of crypto are sitting astride of — not operating within — regulatory frameworks that protect investors and consumers, guard against illicit activity, and ensure for financial stability. Currently, we just don't have enough investor protection in crypto finance, issuance, trading, or lending. Frankly, at this time, it's more like the Wild West or the old world of "buyer beware" that existed before the securities laws were enacted. This asset class is rife with fraud, scams, and abuse in certain applications. We can do better.

And from the interview: I think that registration is a way to bring a lot of the market into the public-policy framework, into the investor-protection framework, the anti-money-laundering and tax-compliance framework. ... Jay Clayton said it pretty well in February 2018 in congressional testimony — that he hadn't seen a token yet that didn't pass the Howey Test. In 1933, Congress included a definition of security that was pretty inclusive, and the Supreme Court has reaffirmed it multiple times. You exchange money with some common enterprise, and you're anticipating profit based upon the efforts of that common enterprise. There's been about 5,000 initial coin offerings or projects. Some of them failed; some of them were frauds and fake. About 75 or 80 purportedly have market caps over $1 billion. And this is a $2.1 trillion global asset class. I think it's of a size that we need to address, and seriously address. Anything that we do to bring more investor protection to this Wild West of the crypto market, I think, has benefits.

As Wieczner writes, "Gensler is a traditionalist in the sense that he believes the laws currently governing the market, which date back to the Great Depression, are sufficient to handle modern inventions like bitcoin." I think a lot of crypto people would disagree with that, but it's obviously the SEC's position. Finally, people are worried about bond market liquidity: Following the challenges of the spring of 2020, I believe we can build greater resiliency in both money market funds and open-end bond funds. I've asked staff for recommendations to address those issues, building upon feedback we received on the President's Working Group report as well as other information. … Given significant growth in open-end funds and some lessons learned last spring, I believe it also is appropriate to take a close look at this $5-plus trillion sector, to enhance resiliency during periods of stress.

You don't hear so much anymore about the "illusion of liquidity" created by bond mutual funds, which in periods of stress might face redemptions, dump their bonds and lead to a worsening fire sale. But it's on the SEC's radar. Here at Money Stuff we always enjoy a good euphemism for "bribes," but I confess this one — which seems to be pretty standard? — was new to me: One aspect is the role of intermediaries, often favored by governments in the region. The so-called briefcase companies act as conduits for traders' bribes to officials, taking a cut and directing state business back to the traders. Glencore was a dominant player in Nigeria, Chad, the Republic of Congo and Equatorial Guinea, and says it no longer uses intermediaries as part of a revamped and cleaned-up operation. "An issue that comes up with trader corruption is agents and intermediaries in the mix," said Alexandra Gillies, an adviser at the Natural Resource Governance Institute, which seeks to stamp out corruption in emerging market resources. "Clearly it's the top modus operandi for how these schemes work."

It is from a story about a Glencore Plc oil trader who confessed to paying bribes, through intermediaries, to African government officials. If you just wire money to a government official, that is a bribe and it's pretty obvious. But if you wire money to a well-connected local consulting firm, you are paying reasonable consulting fees for an expert with local knowledge who can give you guidance on how to win deals legitimately. And if the consulting firm keeps 10% of the fee for itself and stuffs the rest in a briefcase to hand to a government official, well, how were you supposed to know? Friend of Money Stuff and NFT-issuer-avant-la-lettre Sarah Meyohas has a new non-fungible token, which she calls "The Non-Existent Token" and which is … I don't know, a Ponzi scheme? HOW IT WORKS Each bid must be 10% higher than the one before. The previous bidder will immediately receive their money back + 5% (minus gas fees). The rest is the artist's royalty. A winning bid receives an NFT in their wallet of a bubble. As soon as there is a subsequent bid, the bubble passes on to the next winner. The previous transaction will become a receipt which advertises your return. A portion of the artist's proceeds will be allocated to carbon offset credits, making this a carbon neutral project. ... The auction goes on forever. You may be the winner for a year, or more. Someone can always outbid, as long as the ethereum network is still running.

Why not. Meyohas's first appearance in Money Stuff was when she manipulated penny stock prices for art. "Her show opens tonight," I wrote, "and you should go see it, especially if you work for the Securities and Exchange Commission." Now she's go a (fully disclosed!) Ponzi for art, I approve. When I wrote about NFTs last week, Matt Harris wrote an interesting Twitter thread in response, arguing that NFTs blur the line between "investing" (buying things for their expected cash flows) and "consumption" (buying things, as he put it, "largely for utility and because they bring us satisfaction, meaning and/or happiness"): In new and unusual ways, we are seeing that line blur, as exemplified by the Reddit communities who coordinate to drive up meme stocks, surely for profit but even more as a sign of tribal identification, as well as by NBA Top Shot and the current fever around art NFTs. It's always been blurry. As a kid, I didn't collect baseball cards because I would entitled to a % of Fred Lynn's salary. But the fact that I could create value through collecting added meaning to the pursuit, turning it from a trivial hobby into something substantial. Buying a pack of baseball cards was "shopping", but the prospect of financial gain separated it from mere commerce, even if in the eyes of the purists it didn't elevate it to real investing. Observers can mock the NFT movement, and like all new things, there are risible aspects. Personally I find it an interesting new seam that sits between consumption and investment, with powerful combinatory features of each that make it more compelling than either alone.

I think that this is correct, as an analysis of NFTs and as an optimistic case for some of them. But I also think that a lot of actually existing NFTs have almost no consumption value outside of participating in a bubble: You don't buy them because you enjoy looking at a digital picture of a rock that you could look at for free anyway; you buy them because (1) you hope their value will go up and (2) it is fun to be part of a mass online event that involves pumping up the price of a digital picture of a rock, that's just funny. I am not convinced that that is a durable source of consumption value: Sure it's fun to buy the digital rock now, but will it still be fun in a year when it is less novel and people have moved on? Anyway I appreciate that Meyohas's "non-existent token" tries to abstract out just the "participating in a bubble" aspect of NFTs and sell it on its own. Libor replacement reaches Wall Street's leveraged loan market. Green Steel Becomes a Hot Commodity for Big Auto Makers. Don't Treat Us Like Terrorists, Insider Trading Suspects Say. Goldman Sachs CFO Scherr to Depart in Latest Executive Reshuffle. Apple Must Decide How Badly It Wants 30% Fee After Court Ruling. Facebook XCheck. Coinbase to Raise $1.5 Billion in Bond Sale. Steven Cohen to Invest in Crypto Quant Trading Firm. Energy Prices in Europe Hit Records After Wind Stops Blowing. Evergrande Hires Restructuring Advisers as Crisis Escalates. "A shortage of Afghanistan's own currency, the Afghani, could be worsened by the fact that the country can't print money itself." 'Mob Errand Boy' Who Became Witness Can Practice Law Again. Lab-grown woolly mammoths could walk the Earth in six years if geneticist's new start-up succeeds. Taco Bell tests 30-day taco subscription to drive more frequent visits. "I don't have a child, much less one who's a vessel for a demon; nevertheless, I felt misunderstood." If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] For that matter, will the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission go after this person? The general division of labor in U.S. law is that virtual currencies like Bitcoin and Litecoin are "commodities," subject mainly to CFTC regulation. As the name implies, the CFTC mainly regulates commodities *futures* (and other derivatives), not spot commodities trading; the CFTC is not in charge of Bitcoin exchanges. But the CFTC does have the ability to go after fraud and manipulation in the spot market: "While its regulatory oversight authority over commodity cash markets is limited, the CFTC maintains general anti-fraud and manipulation enforcement authority over virtual currency cash markets as a commodity in interstate commerce." [2] This can mean "we will invest indiscriminately in companies that do good things and companies that do bad things," or instead "we will invest *only* in companies that do bad things so we can turn them around." The first approach is basically indexing; the second is (more or less) ESG activism. [3] From Wieczner's article: "In other ways, Gensler fashions himself a progressive. He's the first SEC chief to fully reject the 'chairman' title in favor of the gender-neutral 'chair.' (Mary Schapiro, the agency's first female head, is still listed as chairman in her official bio.)" |

Post a Comment