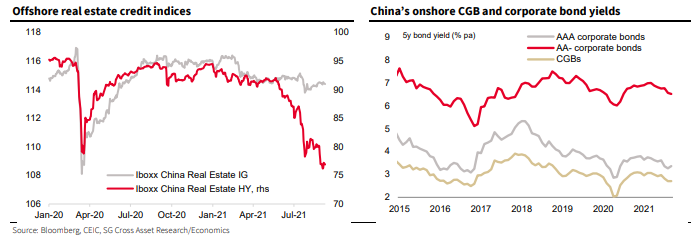

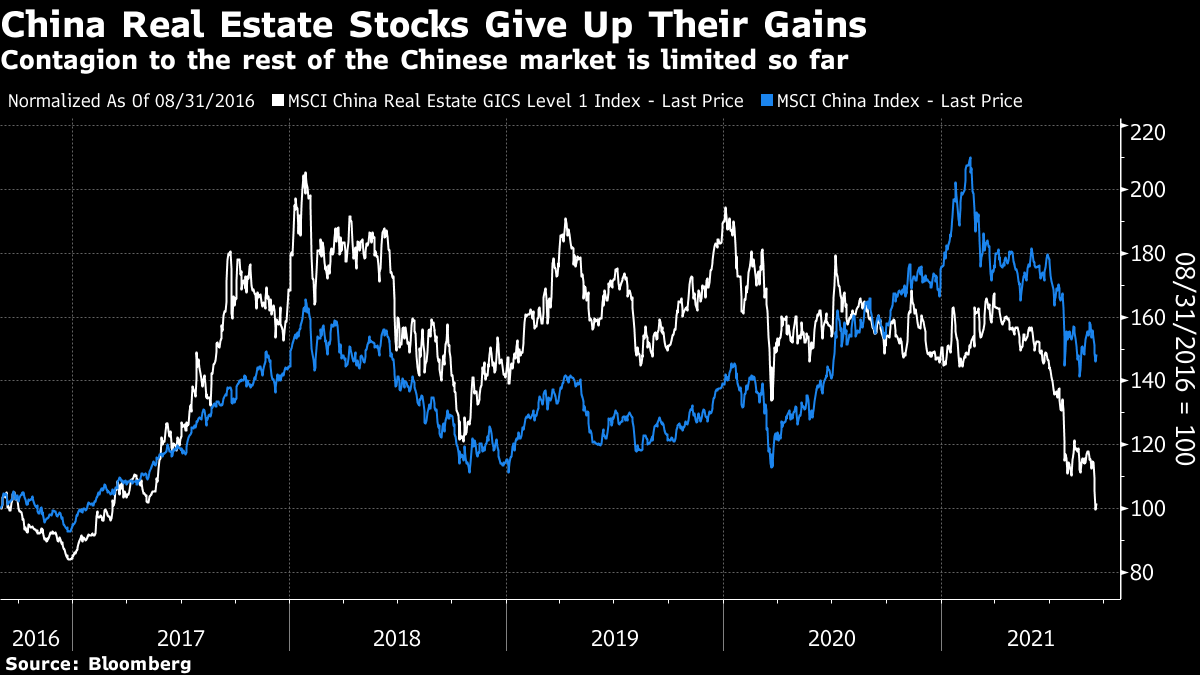

| As the week starts, Hong Kong is gripped by the fast-developing crisis at real estate developer China Evergrande Group, which is on the brink of skipping payments due to banks. With mainland Chinese markets closed for a holiday, this has translated into a nasty selloff in Hong Kong, which has seen the Hang Seng Chinese Enterprises Index (often referred to as H-shares) touch its low from the pandemic shutdown last year:  Plainly, this is a potentially huge moment. Understandably, Evergrande has almost crowded out the hubbub of speculation over the dozen central bank meetings to come this week, headed by the Federal Reserve. So here is the key question: What kind of a moment will the Evergrande Moment be? Will it be a Minsky Moment, akin to the Lehman collapse? Or will it be more akin to the LTCM Moment? Or might it just be altogether less momentous? To measure this we need to resuscitate another concept of which many of us thought we had heard the last more than two decades ago: Asian contagion. How much effect will Evergrande's troubles have on the rest of us? To define the terms: a Minsky Moment, named for the economist Hyman Minsky, happens when confidence breaks after a prolonged period of speculation. The most famous example is the Lehman Moment, which came in 2008 when Lehman Brothers went bankrupt as a result of excessive subprime lending, and the knock-on effects brought the global financial system to a standstill. An LTCM Moment is named for the implosion of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund in 1998, which also followed a sudden loss of confidence after a period of excessive speculation. The difference between LTCM and Lehman lay in what the authorities did about it. After LTCM, the Federal Reserve banged the heads of creditors together to bail it out, and then cut interest rates. That sparked the last mad 18 months of the 1990s bull market. The Lehman Moment happened when the government decided not to repeat the LTCM experience, because it had created too much moral hazard — the irresponsible behavior that comes when people are sure they will be bailed out. The result was the worst U.S. market crisis in eight decades, and arguably the greatest global financial crisis ever. Whatever kind of moment this is, it has arrived. Major banks have already been told by Chinese authorities that they won't receive interest payments due on Evergrande loans on Monday (when this newsletter arrives). Bloomberg also reports that it's unclear whether Evergrande will pay about $84 million of dollar-bond interest due Thursday. The welter of research into Evergrande in the last few weeks comes to a clear consensus. Yes, Evergrande is big enough to create a Minsky Moment within the Chinese market. But we should expect the response to be far more LTCM than Lehman. For the short term, therefore, this implies a nasty and messy market, but not an all-out implosion. It also implies a distinct risk that the Chinese authorities make the same mistake as the Fed under Alan Greenspan 23 years ago, and unwittingly create the conditions for one last disastrous bout of speculation, despite having precipitated the pressure on Evergrande. As with Lehman and LTCM, this problem has advertised its presence. This is how the yield on Evergrande debt due in four years has moved since it was issued:  If the yield has topped 60%, the market takes it as a given that not all of the coupon is going to be paid. Meanwhile, if we look at the performance of high-yield Chinese real estate debt (as measured by the FTSE ABBI Asian debt index), and compare it to the total return on the S&P 500 since the post-GFC bottom in March 2009, we discover that until the last few weeks, lending to low-quality Chinese property developers had made more money that investing in a stock market populated with all the monopolistic monsters that were busily making profits from the rest of the world. That is plainly madness. There have been worries about a potential Minsky Moment in the Chinese property market for the best part of a decade now. This chart amply justifies those worries:  To gauge the precise effects on the biggest names in the Chinese high-yield index, it is worth looking at this Twitter thread from Jens Nordvig of Exante Data Inc. There is evident contagion in the real estate sector; yields of companies in other industries, including even banks, haven't moved much, at least yet. And, as this chart produced by Societe Generale SA shows, there has been no contagion from high-yield to investment-grade debt:  Something similar is afoot in the Chinese stock market, which topped earlier this year after what had appeared to be an unsustainable rally. Its initial dive predated the problems for property stocks, and it has largely stayed stable over the last month as real estate has taken a further leg down. With plentiful stock-specific reasons for problems elsewhere in the index this year, as the government clamped down on various large technology companies, it's fair to say that the Evergrande situation has caused no significant contagion so far:  The anecdotal evidence about Evergrande is alarming, and painfully reminiscent of the U.S. subprime crisis. Creditors are being offered unsold properties in lieu of payment, for instance; not exactly cause for reassurance. The news from the broader real estate market is terrifying. China is pockmarked with speculative properties and it isn't at all clear that there will ever be buyers for them. This is terrible collateral. So why is there still relative calm? It boils down to a close reading of the Chinese authorities' intentions. They have no interest in staging their own Lehman. There has been alarm about the possibility of a Minsky moment for years in Chinese circles, frequently voiced out loud. Officials know what could happen and are determined to prevent it if they can. Efforts to rein in credit have been going on for years. And Evergrande is in trouble largely because the government itself decided to clamp down on property developers through the "three red lines" policy last year. Governments can easily make mistakes, of course. But the Chinese plainly intend this to be more LTCM than Lehman. The company has hired Houlihan Lokey and Admiralty Harbour Capital as joint financial advisers to explore "all feasible solutions" while regulators in Evergrande's home province of Guangdong have dispatched accounting and legal experts, including a team from restructuring specialty law firm King & Wood Mallesons. To quote Eli Lee, head of investment strategy at Bank of Singapore Ltd.: This was interpreted as a signal that the Chinese government could be laying the groundwork for a restructuring of Evergrande and its debt, which could be one of the largest to-date in the country. Regulators have expressed that Evergrande, as the country's second largest developer, poses potential systemic risks.

Andrew Lawrence of TS Lombard states the same opinion more cynically: An Evergrande restructuring looks inevitable, but what form it will take is far from clear. Given that Evergrande's excessive leverage and liquidity dependency are well known, it would be reasonable to expect Beijing to have a plan. If not, things could get messy. Exorbitantly wealthy owners, speculative bubbles, poorly financed businesses with strong prospects for default, monopolies/oligopolies and rampant corruption are all evidence of a lack of meaningful external discipline on an industry.

Another reason to expect the Chinese government to do something to ensure an orderly process is that they have no choice. To use another familiar phrase from the Lehman debacle, Evergrande is far too big to fail. This is from the veteran investment analyst Ed Yardeni: It's huge. Evergrande was until recently China's second-largest property developer, with $110 billion in sales last year. It has $355 billion of assets across 1,300 developments, many located in China's lower-tier cities, a July 27 Reuters article explained. In recent years, the company has branched into unrelated businesses including electric cars, football, insurance, and bottled water. And recently, the company has been trying to sell its businesses, apartments, and properties at deep discounts to avoid a cash crunch. Evergrande has 200,000 employees and hires 3.8 million workers every year for project developments.

A final point is that we also have an idea of the likely playbook from the failure of the smaller but even more interconnected Baoshang Bank two years ago. To quote Wei Yao of Societe Generale: While we do think that Evergrande is systemically important, we also reckon that Chinese policymakers have the willingness, capability and knowhow to stem a financial market meltdown. On this front, the default of Baoshang Bank on its interbank liabilities in May 2019 is a good reference. Compared with Baoshang at the time of default, Evergrande has much more total debt, but similar amount of liabilities to financial institutions and in the capital markets. Also, Baoshang had more complex ties in the financial system (with over RMB300bn interbank liabilities with over 700 counterparties) and, very importantly, its default was a complete surprise.

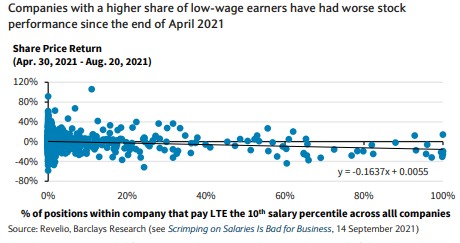

The Baoshang episode showed, to quote Yao, that avoiding a systemic liquidity squeeze was "the absolute priority for the the People's Bank of China" and that it had the means to do so. Policy makers are also able to buy time to make a restructuring less painful. To be clear, an LTCM outcome isn't great. It leaves the risk of more moral hazard. And while the PBOC can probably avert a full-blown credit crisis, it can't stop the weakness of the property sector turning into disappointing economic growth for China. Many small savers and hopeful property buyers will inevitably be hurt by whatever deal can be thrashed out — and the precise shape of that deal will matter a lot. But for the moment, world markets are nervous that this could be another LTCM, while comfortable that it won't be a Lehman. On balance, both of these points look reasonable. Now let's see what happens. I went into detail on Evergrande today because Lisa Abramowicz reminded me that I needed to do so in our Friday Risks and Rewards livestream. I hope it's interesting:  Points of Return has pointed out many times that wages are rising, and — interestingly — that earnings for low-skilled workers are rising faster than for high-skilled workers, in a way that hasn't been seen in decades. This has positive implications for social harmony, It also has negative implications for inflation. And if you're interested in buying stocks, it has negative implications for companies that have come to rely most heavily on cheap labor. The following chart from Barclays Plc shows the relationship between the proportion of a company's workforce whose pay is in the lowest decile (on the horizontal axis) and its share price since the nadir last spring. It shows a slight but statistically significant relationship; companies with more lower-paid workers tend to have had poorer stock market performance:  For those who still believe capitalism might have the means to redress some social injustice, this should be good news. Companies whose model was based on exploiting people are now under pressure either to give up on hiring (and presumably make less revenue) or raise wages (and presumably cut profit margins). To rectify social injustice, or just to make money, it might be an idea to buy stocks in companies that pay their workers well, while shorting those that don't. OK, this is not much of a survival tip if you are sitting at a computer and have to get some work done. Quite the reverse in fact. However, if you'd like to wallow in a nice long list that will take you to all the corners of the internet, and bring back memories of all the most important moments in your life so far, you probably want to visit Rolling Stone's fully updated countdown of the best 500 songs ever. It was compiled by a bunch of people with evidently very different tastes, with the final ranking formed quantitatively from myriad different "best 50" lists. Pre-war stuff such as Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit," still probably the greatest protest song ever recorded, is in there. So is stuff from Lady Gaga, and Lorde, and Kanye West. As for the number one, it's a defensible choice which I can respect; undeniably a great song. It's also a good piece of journalism, and the text includes factoids I didn't know about some of my all-time favorite songs. For example, I didn't know that Bowie's Heroes was written about a couple he saw courting at the foot of the Berlin Wall, or that Ian Curtis of Joy Division chose to record Love Will Tear Us Apart in the same studio that had been used by Captain and Tenille to record Love Will Keep Us Together. Probably not something to embark on if you have something to do on a Monday morning, then. But very highly recommended if you have time on your hands. Have a good week everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment