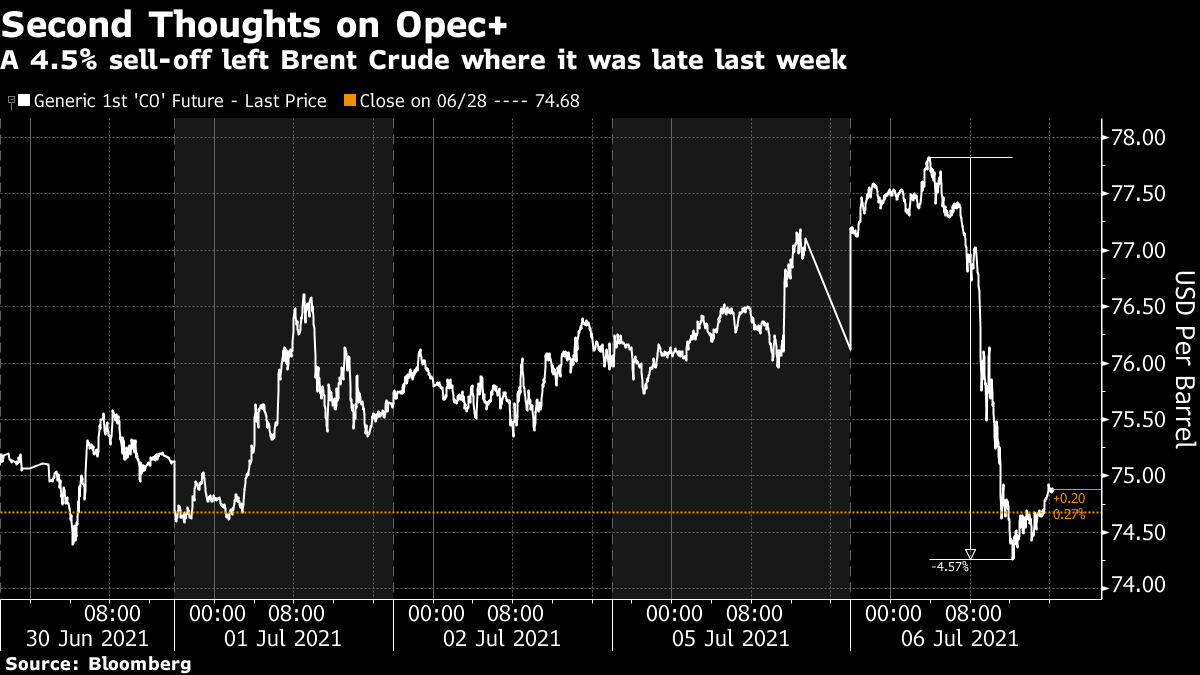

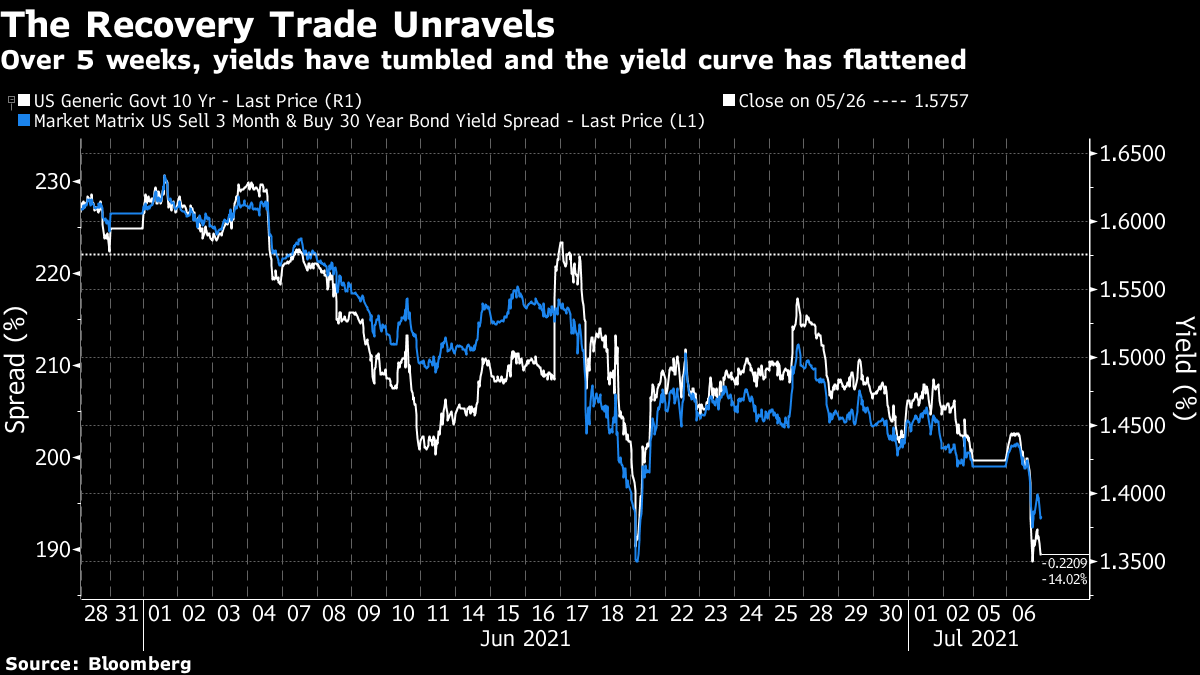

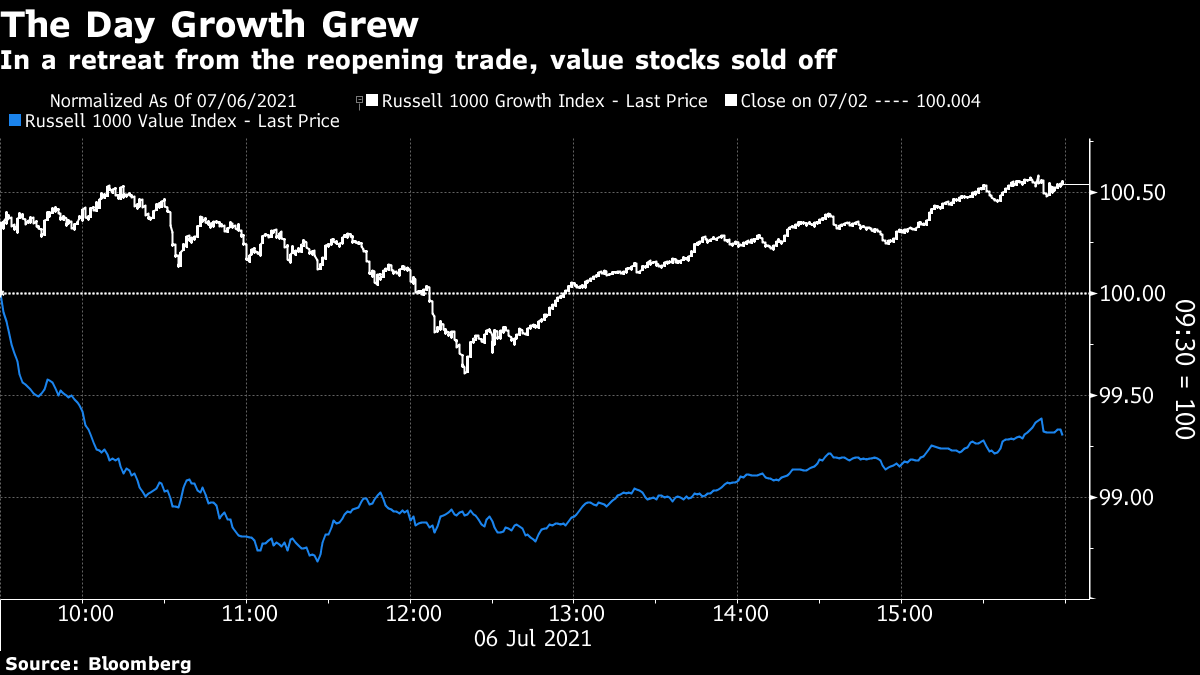

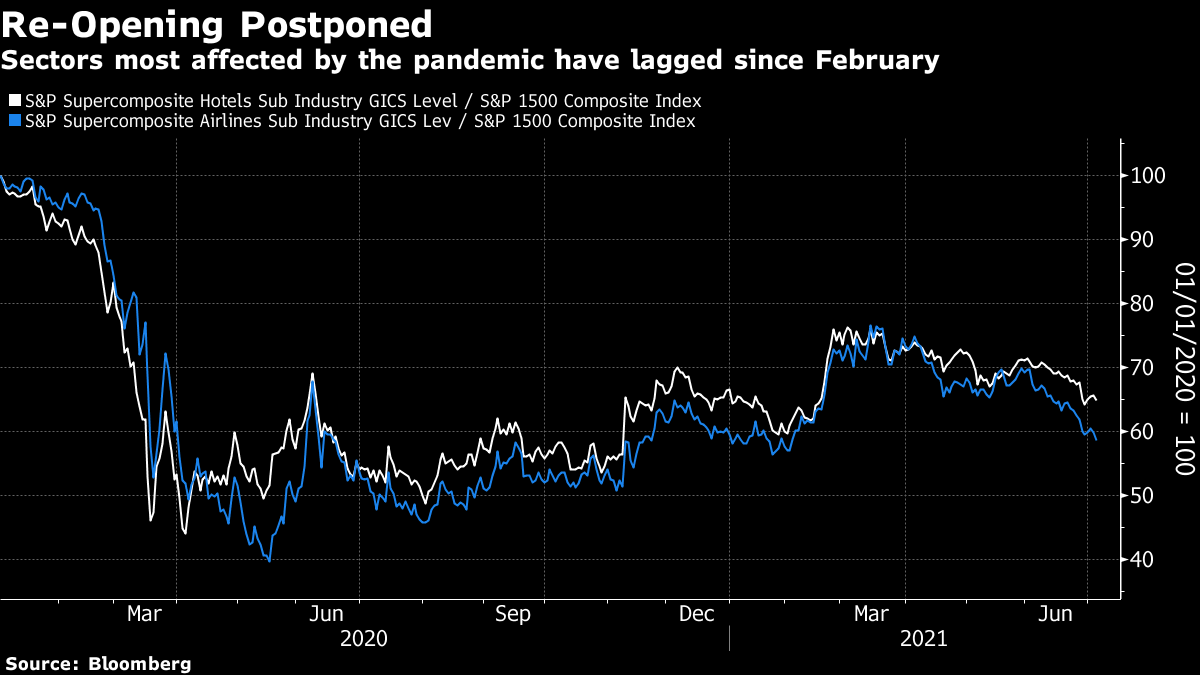

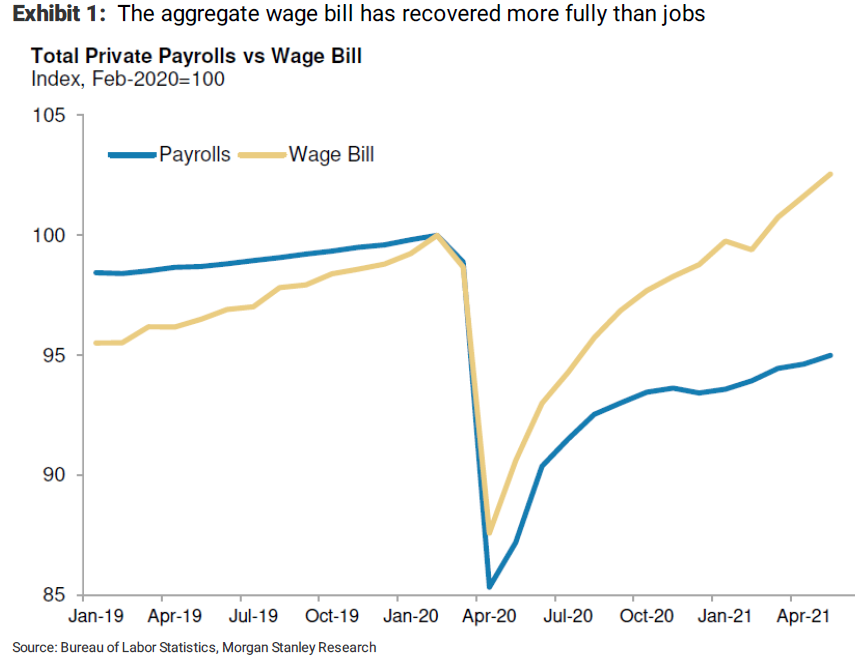

Can the Recovery Trade Recover?As I (thankfully) suggested would be wise, the market had second thoughts on the weekend's failed OPEC+ meeting. Crude tumbled, giving up all the gains made on speculation that the cartel could find itself forcing up prices once more. Oil prices are back where they were at the end of June:  That was only the half of it. Rising oil prices fed into the narrative of a burgeoning "recovery trade" as everyone made themselves richer on the back of a rebounding post-pandemic economy. Every other aspect of that narrative now also seems under threat. Since the beginning of last month, the yield curve has flattened (meaning that the gap between yields on the longest and shortest-dated bonds has grown much narrower) while bond yields themselves have fallen substantially. That directly implies a belief in lower inflation, and a less powerful economy that doesn't need higher rates to rein it in:  Real yields (after inflation), arguably the single clearest indicator of how easy conditions have become, are back to almost exactly one percentage point below zero, based on 10-year U.S. Treasuries. This was a level never seen before the second half of last year. The sharp rise in February has been almost totally canceled out:  Meanwhile, equity markets had a tough day, after setting all-time highs last week — and growth stocks, bought for their reliably increasing earnings, did far better than value companies, which look cheap compared to their fundamentals. This is generally a sign that investors think growth will be scarce:  This tends to confirm a gathering trend. Value stocks have far outperformed growth for the year to date, but nerves about the reopening trade have been escalating for months. Perhaps the clearest example is the performance of the airlines and the hotels, resorts and cruise line sectors compared to the broad stock market. All seriously hit by the pandemic, they sold off horribly last year, and steadily regained thereafter, with a strong push in February as the Biden vaccination campaign took shape. But they have both lagged behind the market badly since then:  So, the recovery trade, and the "reflation trade" that holds we are moving toward a healthily higher level of inflation, is undeniably in trouble. Why? Here are some of the suggested culprits. It's the Economy, StupidMarkets are driven by moves in the economy, and by changes compared to prior expectations. It's perfectly possible for asset prices to do poorly amid basically strong economic conditions if growth is decelerating or disappointing. And indeed, after more than a year in which Citigroup Inc.'s U.S. economic surprise index has been constantly in positive territory, it has now lapsed back to zero. The latest U.S. macro data is no better than expected:  Tougher Times Are ComingAs is widely known, employment is recovering, but so are wages. In fact, the total wage bill is increasing faster than the total in work. That has the potential to strengthen the economy in the longer run, and it is a consummation devoutly wished by many. The problem is that it means lower profits for companies, which have been priced on generous multiples on the assumption that earnings can keep growing. This chart is from Mike Wilson, U.S. equity strategist at Morgan Stanley:  Wilson's comment would put anyone off the recovery trade, at least as it applies to the stock market: The bottom line is that the US economy is booming, but this is now a known known and asset markets reflect it. What isn't so clear anymore is at what price this growth will accrue. Higher costs mean lower profits, another reason why the overall equity market has been narrowing. It also supports our view that equity markets are likely to take a break this summer as things heat up.

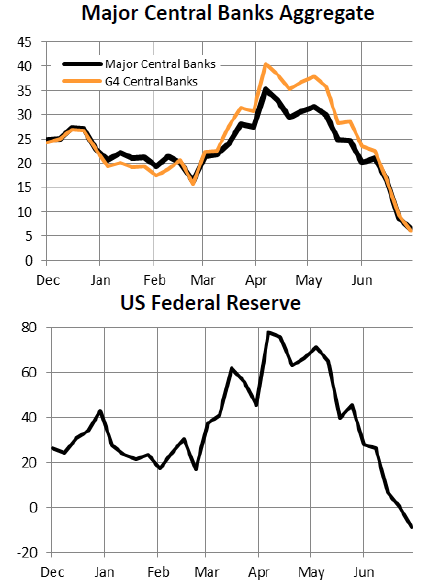

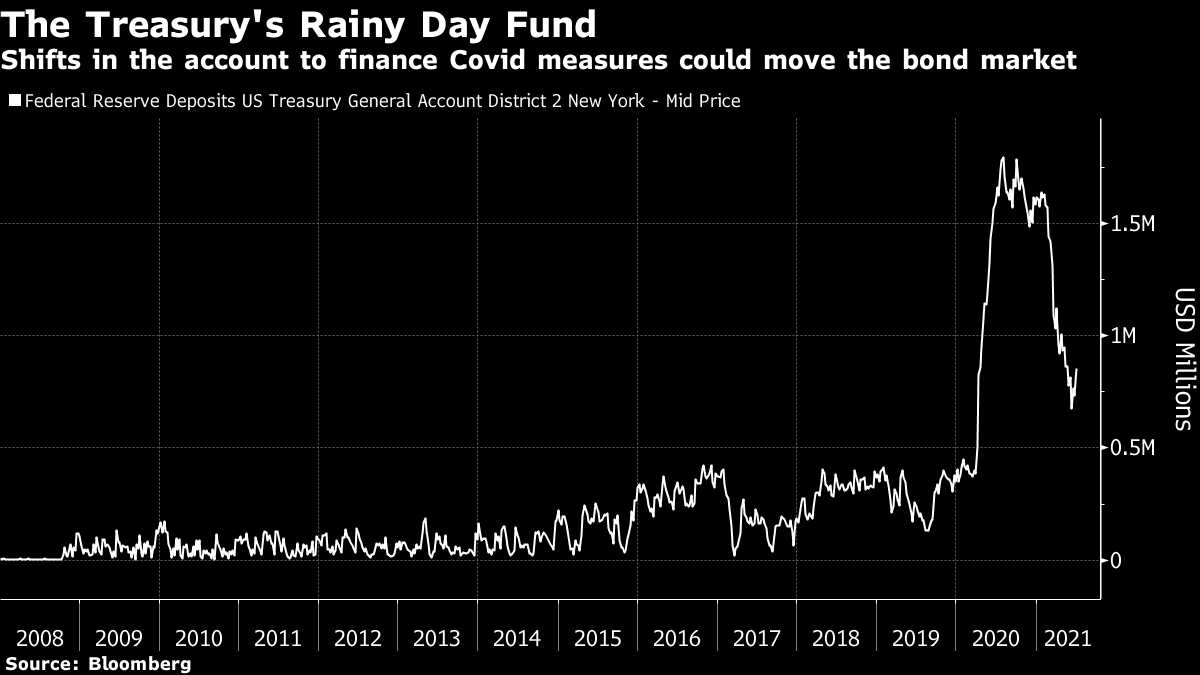

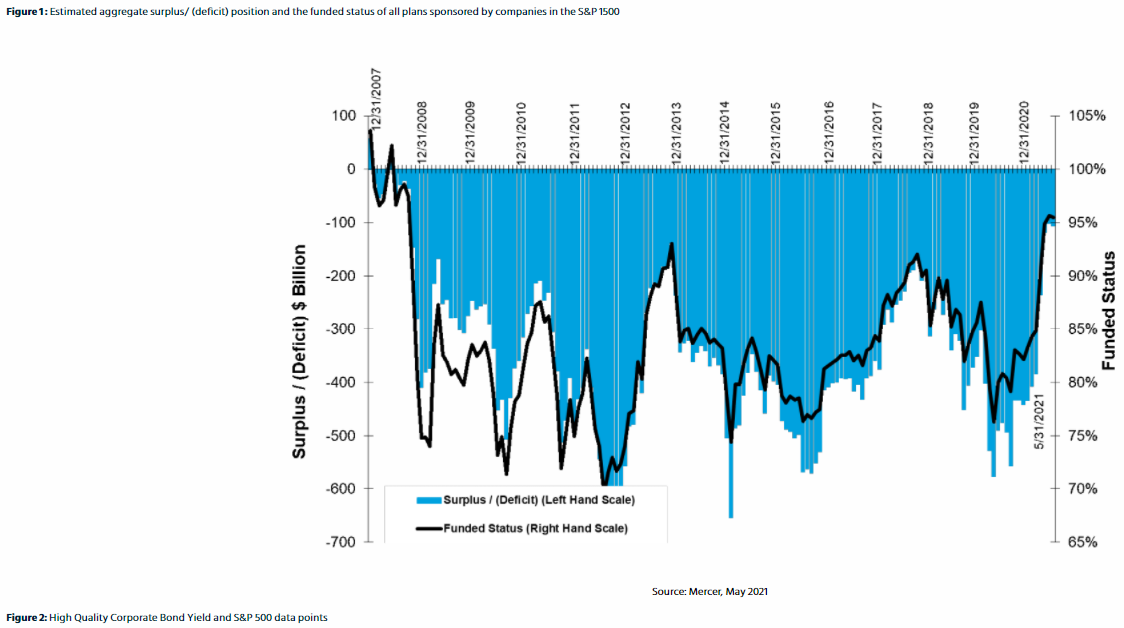

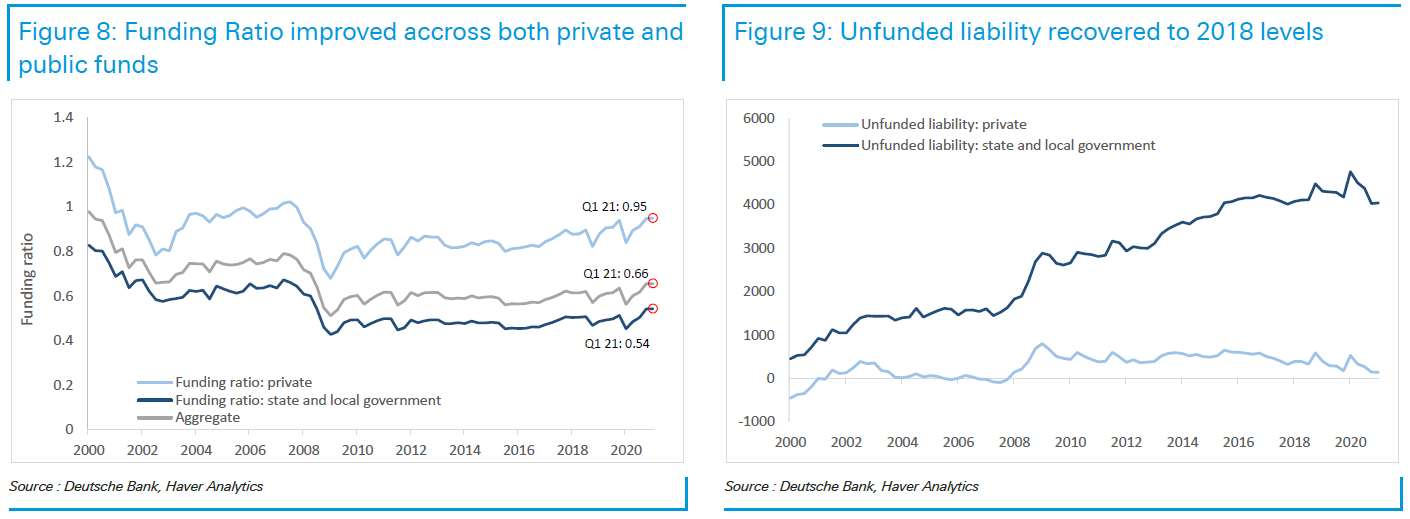

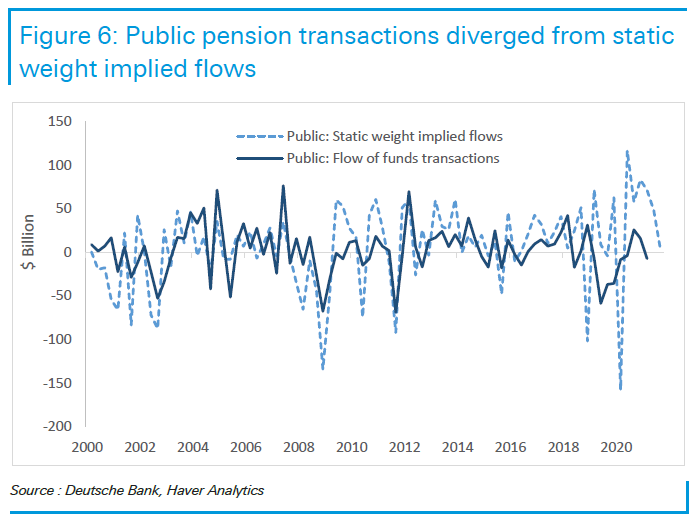

It's the Fed's FaultThis is a hardy perennial, but there's an argument for it. Financial conditions are easy — arguably, absurdly easy. When the Federal Reserve piles into bonds, it distorts the market. It isn't alone among central banks in this, but it does appear to be quite an extreme offender. Conditions in the U.S. have never been so easy, according to the Goldman Sachs Group Inc. financial conditions index. They are also easy in Europe, but it's hard to say they are excessively so. The European Central Bank has merely brought things back to roughly where they were at the end of 2018:  One particular point of complaint is the Fed's treatment of the housing market. High home prices are causing deep and justifiable intergenerational resentment. The last major American economic crash was caused by an overheated housing and mortgage market. So why on earth is the Fed continuing to buy mortgage-backed securities when loan rates have never been cheaper? It diverts money into housing, and serves little purpose beyond distorting outcomes:  If you're a central bank critic who wants to have it both ways (and there are many out there) you can also point to a stealth tightening as the rate of growth in the monetary base slows and even goes into reverse. At the margin, this matters. These charts were compiled by Crossborder Capital Ltd. of London, and show percentage annualized growth in the monetary base. With a recovery that has been buoyed so much by exceptional liquidity, it would make sense for withdrawal of that money to prompt a reassessment of growth prospects:  It's the U.S. Treasury's FaultThis is a less frequently heard refrain. The Treasury keeps an account at the New York Fed. In other words, it issues short-term bonds and holds them in the account, ready to back whatever measures may be necessary. Last year, this Treasury General Account ballooned to more than $1 trillion. This year, the account is being allowed to run down, as it should. But this has the effect of reducing the supply of bonds, while the Fed continues to buy more. The result is that the Fed's total proportionate intervention, and its impact on the bond market, become that much greater. With supply falling so sharply (even as the government merrily announces that it is throwing money all over the place), naturally the price of bonds increases and yields come down. It's yet another perverse effect of the desperate measures taken early last year and their subsequent unwinding:  It's Pension Fund Managers' FaultThis one is a little harsh, but a belief in the way that pension fund managers will behave is helping to move markets. The first half of this year, with bond yields rising (reducing the cost of their liabilities) and share prices rallying (increasing the value of their assets) was something close to nirvana for pension fund managers. As a result corporate pension deficits were almost erased, for the first time since 2007, before starting to widen a little as yields crept downward. This chart is from Mercer, the consulting actuarial group:  But while private sector pensions clawed back to a deficit where assets were only 5% less than liabilities (known as the "funding ratio"), public funds remain in much worse shape, as illustrated here by Deutsche Bank AG. Public funds can barely cover half their liabilities, and the scale of unfunded liabilities is frightening:  Research by Deutsche suggests that in the first quarter, public plans eschewed buying bonds as they normally would, in favor of piling into equities. This will have served them well in the short run, but leaves open the possibility that they will have to catch up by buying more bonds before the year is out. Such a factor may already be underway. According to Deutsche's Jiefu Luo, in the first quarter: Public and private funds collectively added a mere $3.6 billion to their fixed income portfolio while our model suggests this amount would have been much higher at $130.4bn if pensions had rebalanced to maintain the same allocation weight from the previous quarter. The large disconnect between model implied and realized flows points to pent-up demand for fixed income securities further down the road as the equity market is inevitably challenged by Fed tapering.

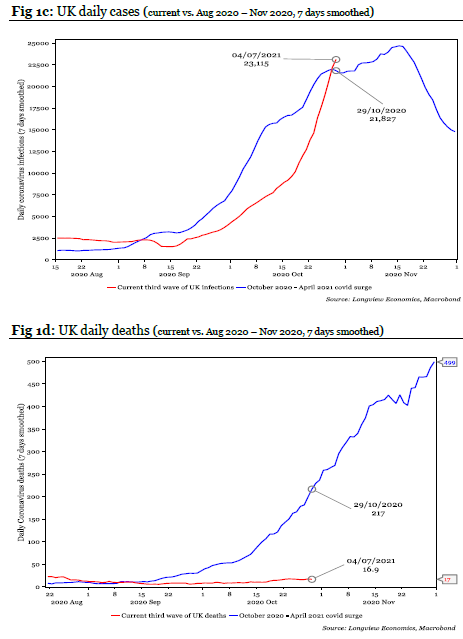

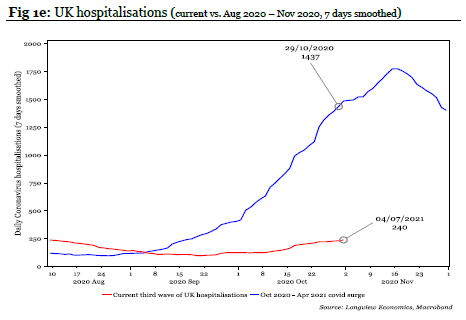

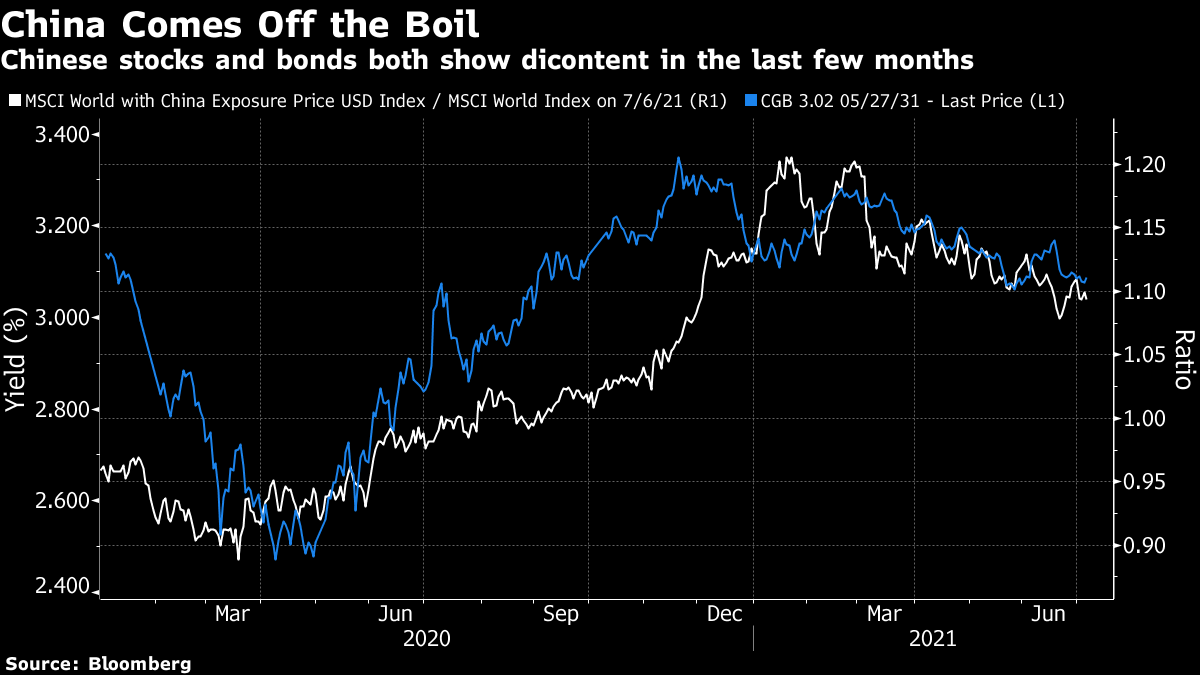

The following chart shows the money that would have gone from public pension funds into Treasury bonds if they had kept their asset allocation static (according to Deutsche's model), and the amount they actually bought:  As with the Treasury General Account, the implication is that bond yields are falling, and the recovery trade faltering, because of a weird technical factor within the bond market that can be canceled out later. Blame the Delta VariantEverything about the Covid pandemic has become politicized, but there is much speculation in buy- and sell-side research that nerves about the latest variants are driving share prices lower. As humans, we can agree in our dislike for a steadily mutating virus that is finding new ways to make us sick. It has plainly led to a resurgence of infections. But maybe there are limits to how far we should take this. The crucial testing ground is the U.K. As the developed country with the most widespread vaccinations and the first to be affected by the delta variant, it can tell us a lot. The bad news is that the variant is infecting a lot of Britons. The good news is that it isn't killing them. The following charts are from Longview Economics Ltd. of London, and compare cases and deaths in the delta outbreak with those during the wave that forced a closedown last fall:  Infections are comparable with what happened last September and October; the death toll is far lower. This implies that the vaccine is doing its job and keeping people alive, even if they are infected. The trend in hospitalizations is also encouraging:  It's notable that the age of people hospitalized in Britain has reduced considerably — and they are much more likely to survive. The conclusion so far is that vaccination is doing what it's supposed to. By immunizing those most vulnerable first, the British authorities seem to have ensured that this outbreak would largely only infect those most able to withstand it. So it is hard to see why this should be taken as such a major reason to doubt reopening and reflation. There is, potentially, reason from the British experience to fear what might happen if the delta variant reaches communities where the elderly largely haven't been vaccinated, as is still the case in some American states. But for now that threat is largely hypothetical. Blame ChinaThis is a popular one. And as the rest of the world is still dependent on China for much of its growth, there is plenty of truth to it. Tuesday's headlines were full of China's latest clampdowns on companies and their listings, on its growing attempt to stamp out bitcoin, and on the travails of Tesla Inc. in the country. Judging by the composite PMIs compiled by IHS Markit (including both manufacturing and services), China's rebound is over. As the country led Europe and the U.S. into the pandemic and out of it, and into the Covid-related slowdown and out of it, this isn't encouraging:  If we look at Chinese 10-year bond yields, and at the performance of the most China-exposed global stocks compared to the market as a whole, a similar picture emerges. Chinese assets have been signaling a slowdown for months, roughly since U.S bond yields peaked. In other words, China started to slow when the recovery trade started to slow:  It's becoming a popular call for macro strategists to assume a crouch and wait for China to crack down on leverage and let its economy decelerate further, now that the Communist Party's centenary celebrations are over. One repeated lesson of the last two decades is that it is always tempting to ignore China. It's a long way away from the trading desks of New York or London. It's dangerous to do so. That was as good a compendium as I can provide for why people now have cold feet about the recovery trade. If you're confident that reflation is coming, you have been given a fresh opportunity to make some money. I'll try to handle that argument tomorrow. Survival TipsAs revealed yesterday, my family spent the long weekend dog-sitting a lovely golden retriever called Hugo. A number of you wanted to see a photo of him. Here he is:  I can confirm that golden retrievers are, indeed, adorable. Particularly Hugo. Even if our cats didn't think so. Cats are great too, incidentally. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment