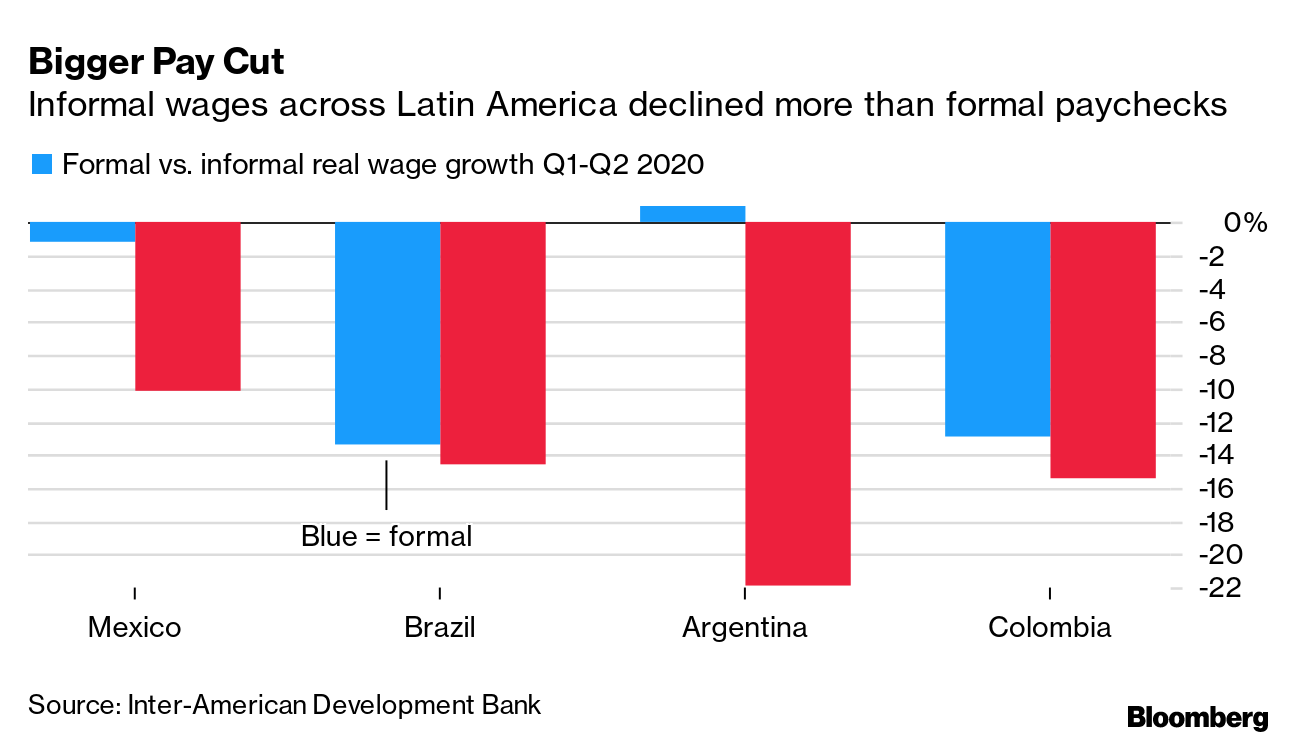

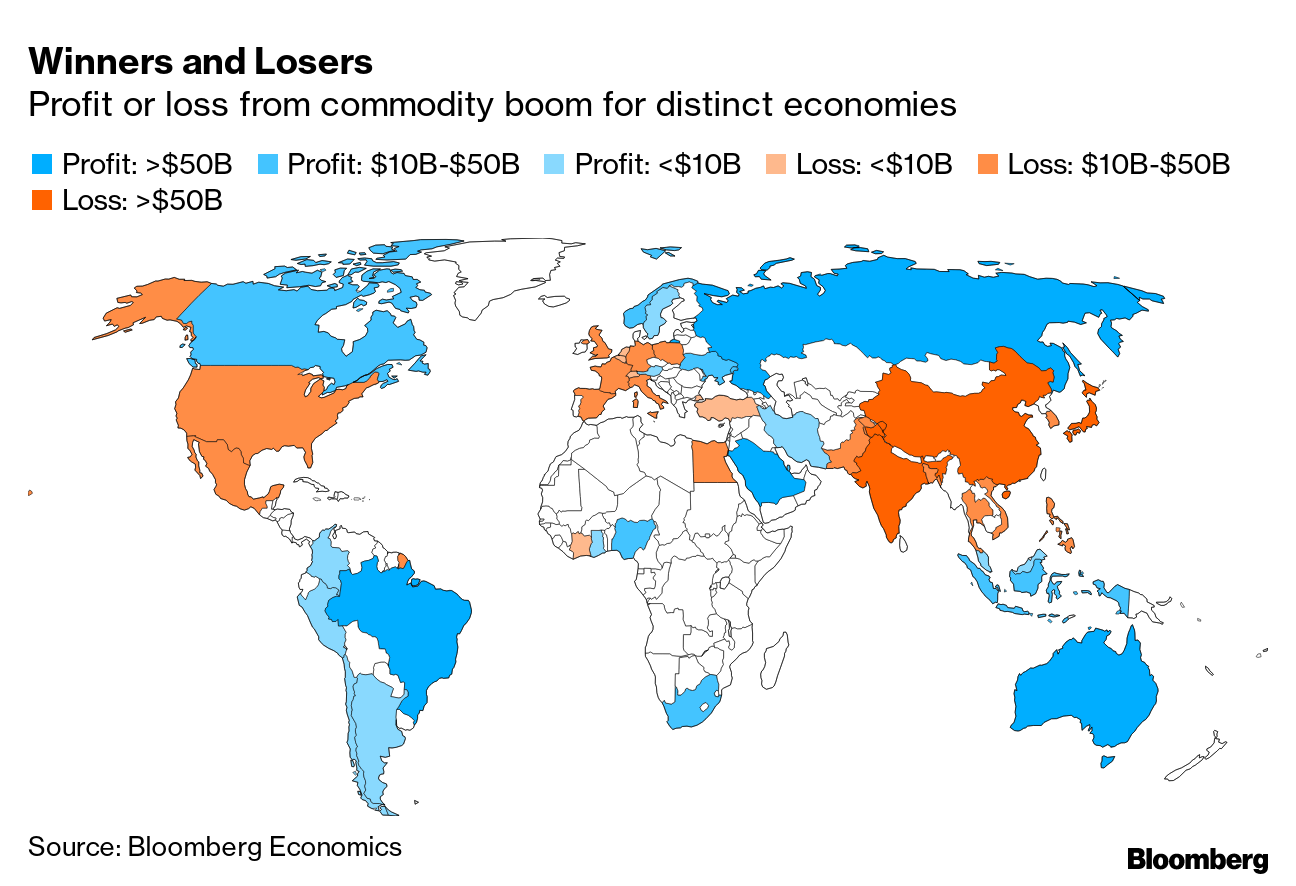

| Hello. Today we look at blue-collar workers in Latin America, the winners and losers from the global commodity boom and the U.S. recovery. Even before the pandemic, Latin America was already a poster child for inequality. Now it's facing a jobs crisis that's poised to worsen the disparities that have stoked political unrest across many nations. In countries including Brazil, Mexico and Argentina, over 60% of the new jobs are informal — that is, typically paid in cash, without salaried contracts — a review of late 2020 showed. Without organization, workers are unable to fight for better wages or basic benefits like healthcare.  Argentine waiters, construction workers, candy-vendors and other informal workers saw a 36% pay cut, taking inflation into account, last year — nearly quadruple the losses for those with salaried jobs. Besides leaving millions trapped in poverty, the surge in the share of precarious jobs is setting up a vicious cycle of economic and social decline: Weaker growth→ lower tax revenue → more social spending → bigger government debt → higher inflation and interest rates → weaker growth. Clawing out of its worst recession in 200 years, the region has three times of the level of informal employment compared with the U.S. and Europe. Street vendors, construction workers and hotel employees work ever more "in the black," as the saying goes in Spanish — not paying a dime of income tax. And they often depend much more on government aid than the white-collar class. The average informal employee in Latin America makes 23% less than the career ladder climber with the same age, education and experience. With local governments having racked up debt through pandemic-relief programs, there's little capacity to loosen the purse strings to embrace "go big" stimulus programs that could ignite stronger economic recoveries. For individuals, smaller paychecks are just one of the many costs to working off the books. In Buenos Aires, when Juan Carlos Moyano lost his salaried job, it cost him the dignity he got treating his hard-working wife to a beach trip. Now he's lost his knees to arthritis and his savings to doctor's visits thanks to grueling gigs off the books. His pay: $1 an hour. — Patrick Gillespie  The gains for commodity exporters will easily outweigh their losses last year as the pandemic spread and crushed demand for raw materials: Bloomberg Economics estimates that $550 billion will shift from importers to exporters in 2021, nearly double the $280 billion reverse transfer last year when prices collapsed. In absolute terms, Russia will benefit the most. China's net exports will drop by around $218 billion — far higher than the figures of around $55 billion for the next-worst off countries, India and Japan. - Peak everything | A moderation in economic growth, commodity prices and central bank support is likely to leave the U.S. economy still well above the sluggish pace of the pre-pandemic years.

- North Korea | The economy last year posted its sharpest drop since a deadly famine in the 1990s due to the coronavirus, natural disasters and international sanctions that have walloped Kim Jong Un's state.

- Politburo support | Beijing pledged more effective fiscal support for the world's second-largest economy and tighter supervision of overseas share listings as policy makers highlighted economic risks in the second half of the year.

- New headwind | The pandemic's impact on global trade risks worsening in coming weeks as more factories across Southeast Asia brace for closures amid one of the world's deadliest outbreaks.

- Expat angst | Singapore's success as a financial hub has long been tied to its openness to global talent. But as the city-state battles to recover from recession, a backlash is underway against overseas workers.

- Green shoots | Japan's factory output and retail sales climbed in June, while Chinese factories are showing some stability. In the euro area, output expanded 2% in the second quarter, beating economists' estimates and dusting off the impact of restrictions that crippled business activity during the winter months.

- Debt limit | The U.S. Treasury is set to start dipping into its toolkit to avoid breaching the U.S. debt limit, as Congress still lacks a clear plan for averting default later this year

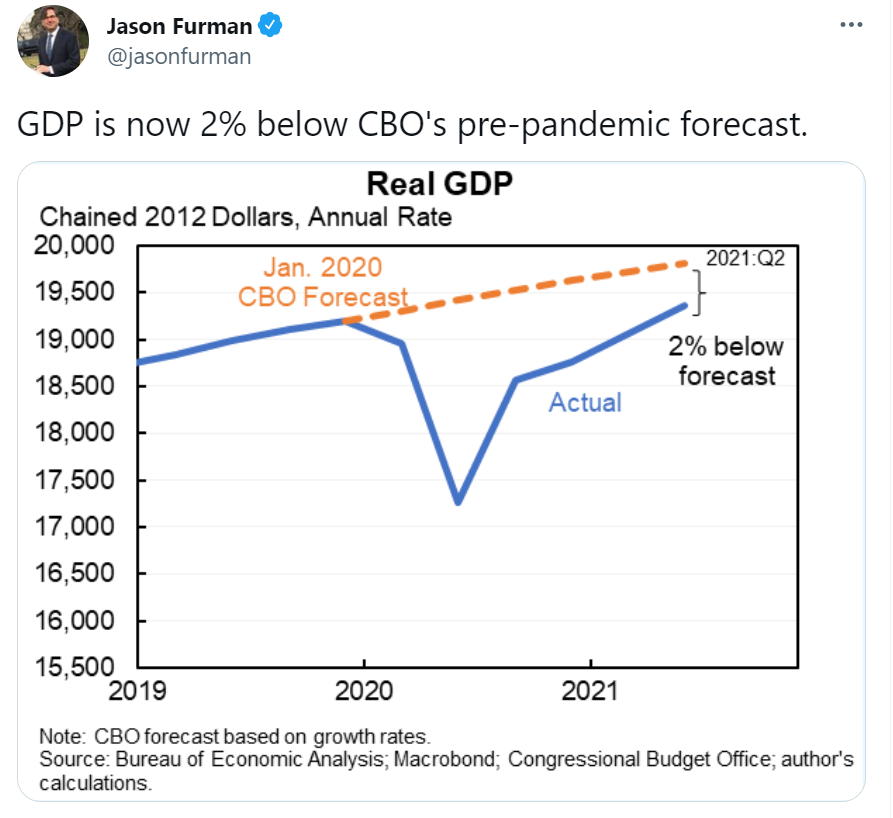

It's taken 18 months for the U.S. economy to regain its pre-recession level of output, according to Deutsche Bank analysts. Their number-crunching suggests that the recovery looks relatively normal despite last year's recession being the largest on record. Credit is handed to the unprecedented level of monetary and fiscal stimulus. The rebound stands in contrast to that following the Great Financial Crisis which took nearly twice as long as the next slowest.  Elsewhere, Stephen Jen and Fatih Yilmaz of Eurizon SLJ Capital reckon the U.S. may be enjoying the start of an elongated expansion, handing investors reason to be upbeat about stocks and the dollar. Again, they point to the likelihood of an aggressive Federal Reserve and the likelihood the government will try to overhaul the structure of its economy. But there is still a ways to go...  Read more reactions on Twitter - Click here for more economic stories

- Tune into the Stephanomics podcast

- Subscribe here for our daily Supply Lines newsletter, here for our weekly Beyond Brexit newsletter

- Follow us @economics

The fourth annual Bloomberg New Economy Forum will convene the world's most influential leaders in Singapore on Nov. 16-19 to mobilize behind the effort to build a sustainable and inclusive global economy. Learn more here. |

Post a Comment