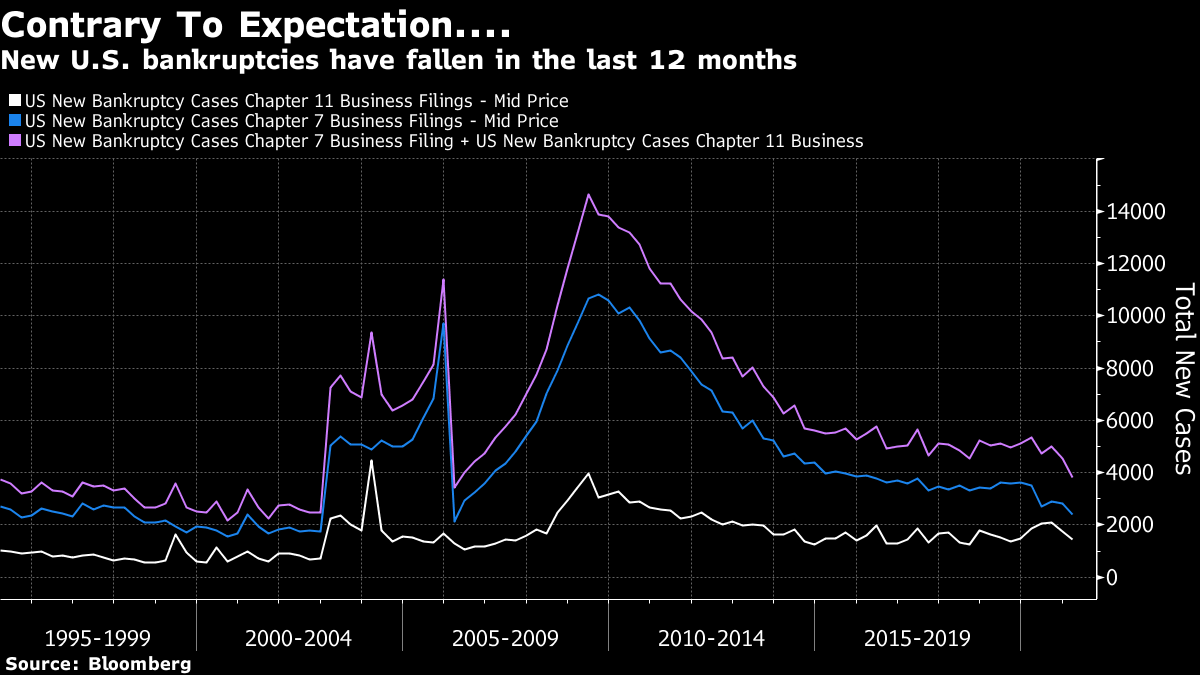

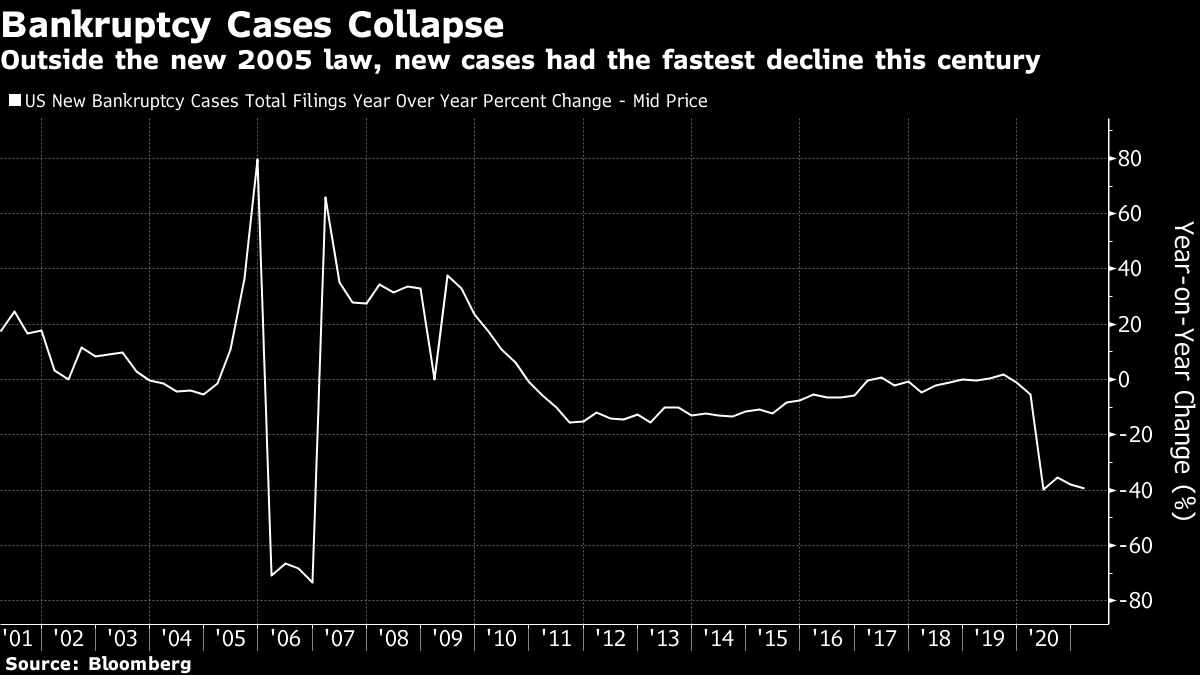

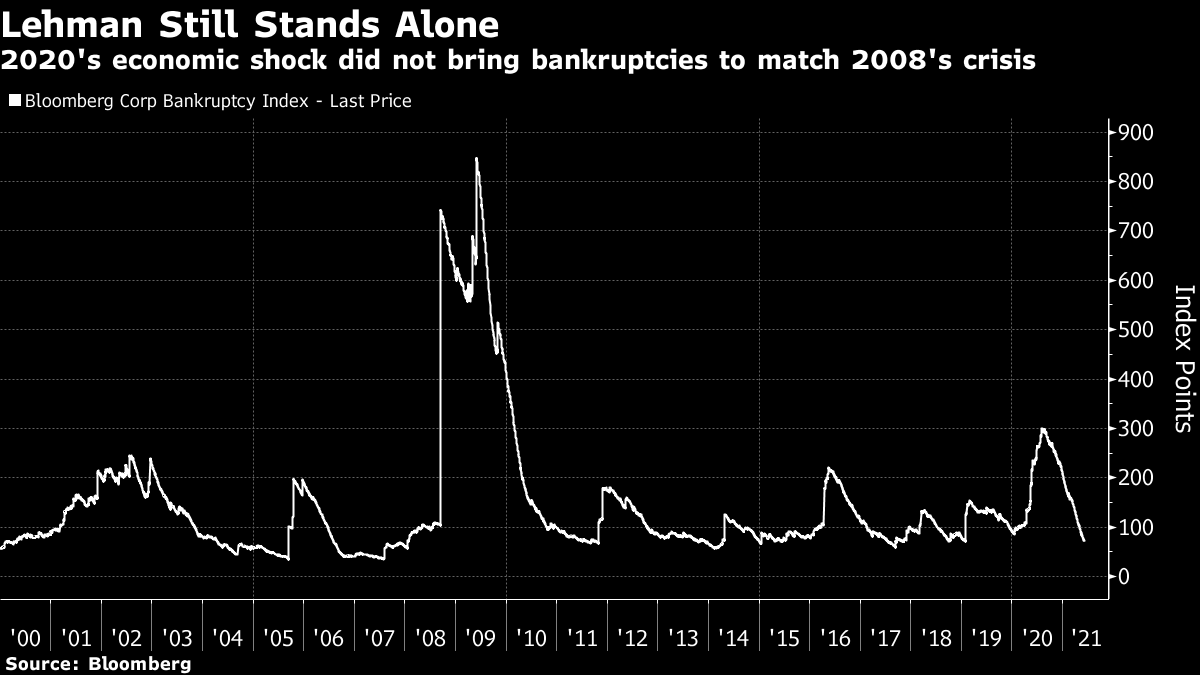

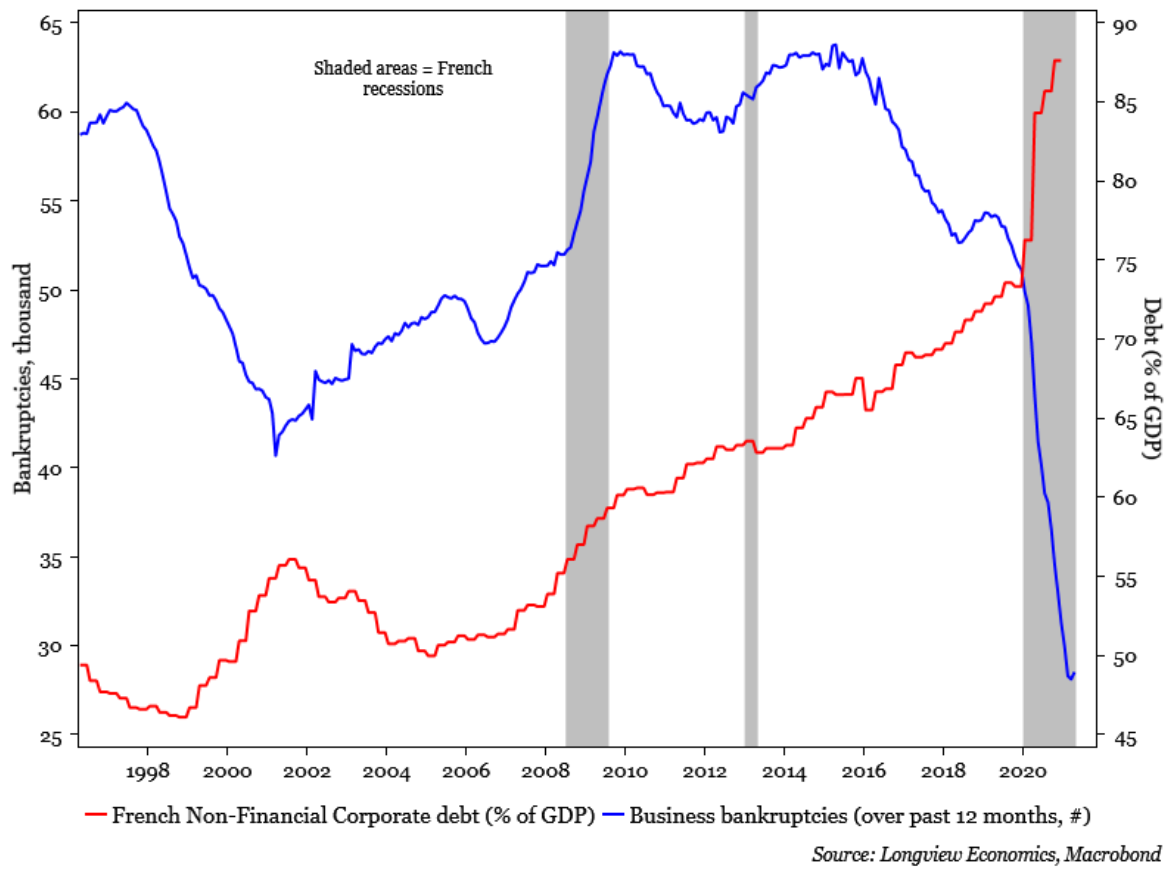

From the Plague to the Zombie ApocalypseA little more than a year ago, we were worried about a solvency crisis. With so many companies suddenly deprived of their revenue, it seemed only reasonable to fear that a wave of bankruptcies and defaults would choke the banking system, bring asset prices down, and present us with a secondary financial crisis to follow the public health crisis of the pandemic. I fully subscribed to this. I thought a solvency crisis was the biggest risk out there. So I now need to report that the opposite has happened. This is how corporate bankruptcies have moved in the U.S. over the last two decades:  Company failures spiked and then dived around the adoption of a new and more restrictive bankruptcy code in the fall of 2005. Since then, the total number hasn't been lower than it was in the last 12 months. The contrast to the credit crisis in 2007 and 2008 could scarcely be more stark. The year-on-year change looks even more deviant. Outside of the distortions caused by the law change, it's the biggest reduction in the number of bankruptcies so far this century — during a brief but brutal recession. How can this even be possible?  If we look at the amount of assets affected, rather than the number of companies, using Bloomberg's bankruptcy index, the last 12 months look even weirder. The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. swiftly followed by Washington Mutual, in the winter of 2008 created a spike for the ages. Since an initial rise in the first months of the shutdown, we have seen a sharp and consistent easing. Bankruptcy business is dwindling:  This isn't a uniquely American phenomenon. In the U.K., which adopted a different approach to mitigating the economic impact on companies, the results appear to have been much the same. This is the progress of corporate insolvencies in England and Wales since 1993. In that period, the corporate death rate has never been lower than it is now:  And the reduction in bankruptcies cannot be dismissed as an Anglo-Saxon phenomenon, either. London's Longview Economics Ltd. offers the following chart of corporate bankruptcies across the Channel in France, along with the total amount of debt outstanding in the country. The contrast is extraordinary:  Recessions are supposed to lead to more bankruptcies, and make it harder for companies to borrow. Rises in debt outstanding, all else equal, should increase the risk of bankruptcies down the line. So what has happened in the last 12 months virtually surpasses understanding. French bankruptcies had steadily declined since the brief recession caused by the sovereign debt crisis, while companies took advantage of the dirt-cheap credit that had been engineered to save the euro to refinance and take on more leverage. When the crisis hit, they were then able to borrow far more, while bankruptcies tumbled. Logic might dictate that an increase in bankruptcies lies ahead. This should mean that debt investors demand a higher yield to compensate them for the greater risk of defaults. In the U.S., this is exactly what has not happened. The spread between the yield on "high-yield" bonds (which might need to be renamed) over five-year Treasury bonds hasn't been this low since the summer of 2007. And we know what happened after that:  This makes no sense... unless we give up on the notion that defaults, and the compensation that investors ought to demand for bearing these risks, should be linked to the strength of the economy. Rather than betting on a remarkably potent and enduring recovery, investors in relatively risky bonds are making a bet on a potent and enduring dose of financial repression, in which central banks keep propping up markets, and effectively force everyone to lend to the government, and to companies, at otherwise uneconomic rates. Such a policy was adopted and sustained in the years after the war, and it's not such a bad bet that more financial repression lies in our future after the pandemic. One of my favorite credit strategists is the resident financial historian at Deutsche Bank AG, Jim Reid, who has been publishing an annual study showing what default rates are predicted by current yields for more than two decades now. After a few years of forecasting serious problems for the credit market (which he also did, accurately, before the implosion of 2008), he appears now to be resigned to financial repression: When I first started in credit markets in the early/mid-1990s I was taught that economic growth was the be all and end all when assessing and forecasting the default environment. However, over the last 15-20 years I've had to change these views and over the last decade or so the default study has incrementally tried to explain why default rates are low relative to history and while they'll continue to stay suppressed even though economic growth has structurally trended ever lower over the last couple of decades.

The biggest explanation is that, over the last 20 years, the authorities have implicitly and explicitly intervened to lower defaults. Implicitly via huge monetary stimulus lowering rates, and explicitly via larger and larger bailouts. This has driven down funding costs relative to economic activity and made it much easier for companies to survive even at lower levels of economic growth. In short, we've moved away from creative destruction and towards an economy with a higher percentage of zombie companies. In the report, we continue to conclude that while this is great for credit investors it's not necessarily good for long-term economic growth.

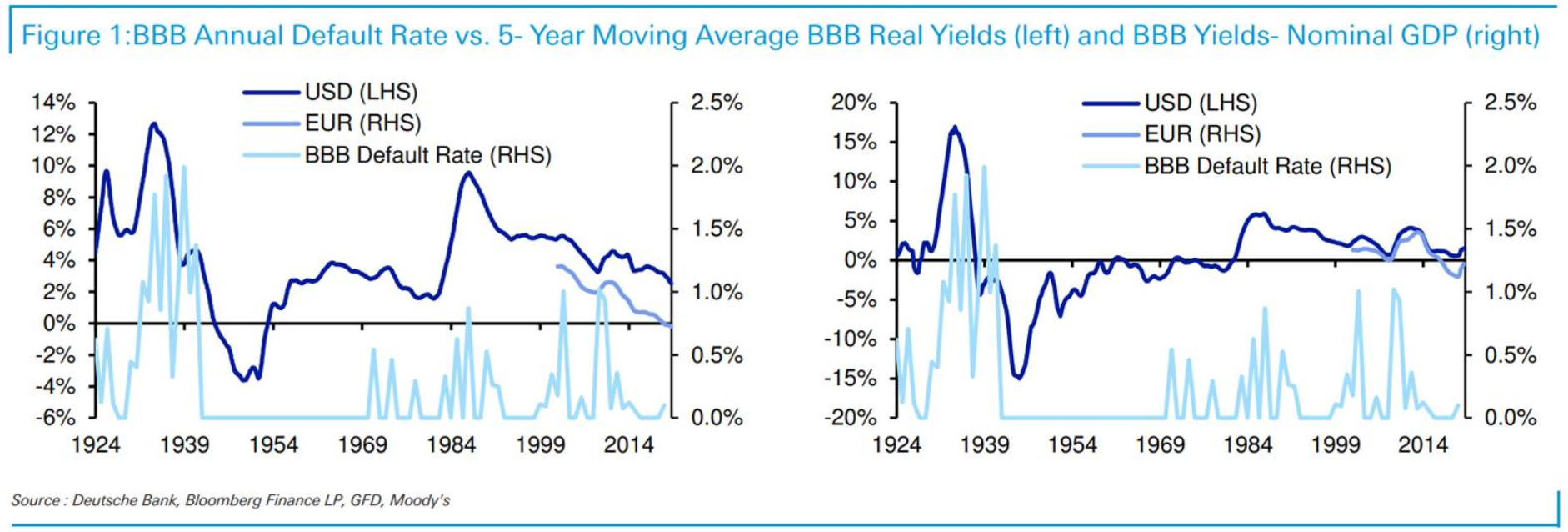

You can say that again. After Reid's default study last year, I suggested that credit bailouts were a Faustian bargain. We could avoid another financial crisis, but it would be at the expense of yet more of the agonizing slow and unequal growth to which we have become accustomed. Weak and unprofitable companies, free of the risk of going to the wall, tie up capital that could be used more productively. Such zombie companies are incapable of growing, but thanks to artificially low interest rates they are able to stay alive, spreading their deadening influence across the economy. It's a debased form of capitalism that almost nobody likes. And as a result there are fewer jobs, traducing the central aim of the Federal Reserve and other central banks at present. With poorer productivity, there is also a risk that such companies need to jack up prices, leading to higher inflation. Reid illustrates how the relationship between default rates and economic growth used to be firm, using data going back to 1924:  Evidently, the relationship is no longer strong. Reid summarizes as follows: Over the last 100 years, defaults have been structurally much lower in periods of low real yields and when corporate yields are low relative to nominal GDP. We think heavy financial repression ahead will mean this scenario holds. How good this will be for productivity is another question.

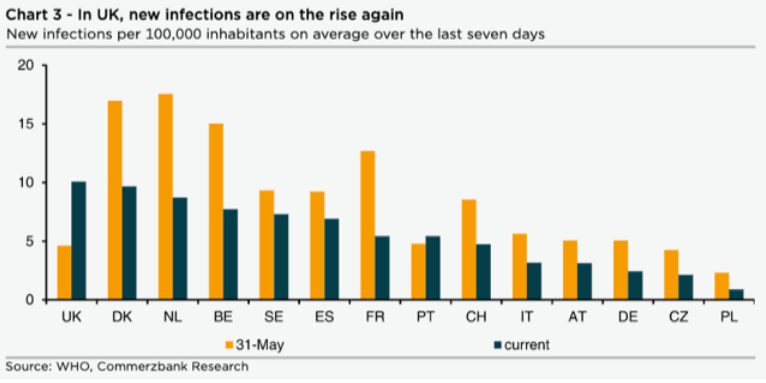

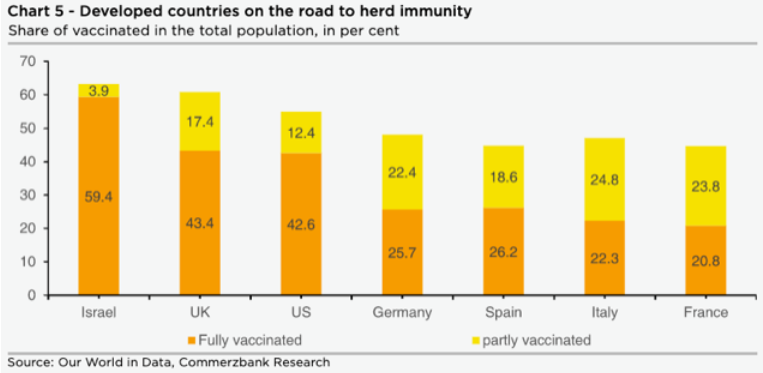

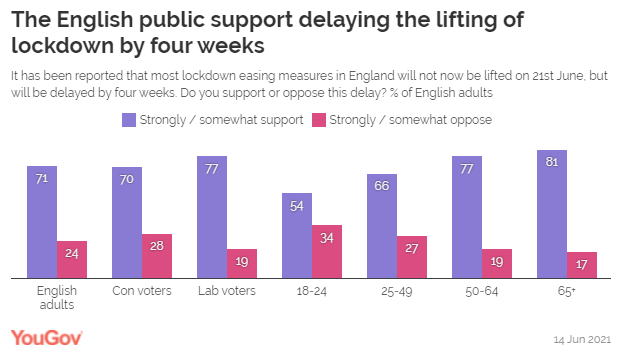

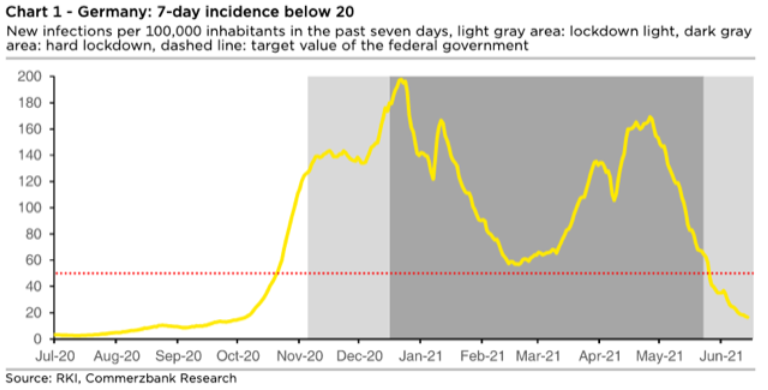

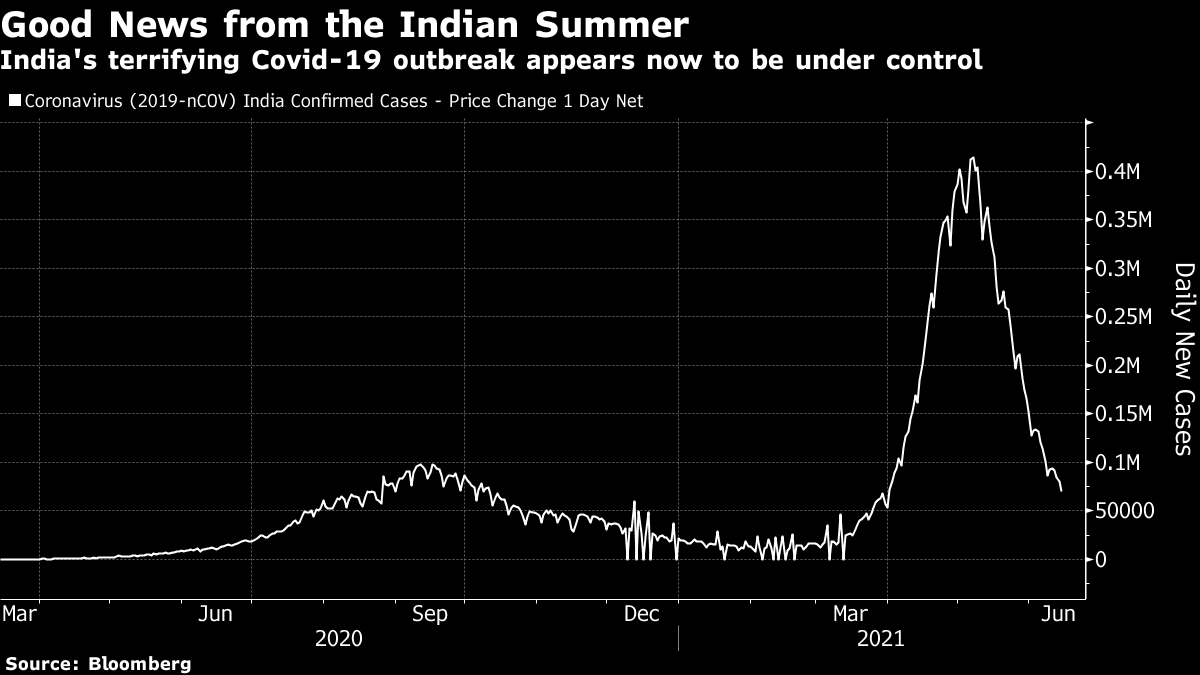

If you think the Fed is serious about allowing inflation to rise, and I believe it is, then you should expect conditions like this to persist for a few years yet. The reduction in insolvencies might well help toward the goal of increasing inflation, but there is every chance that it will vitiate the desire for stronger growth. As for investors, when financially repressed, there's a lack of good choices. Covid: Britain's Midsummer Night's Dream, and an Indian SummerThe fifth anniversary of Britain's Brexit referendum is coming up next week, and the country has managed to set a different course from its continental neighbors. But not in a good way. Boris Johnson, the U.K.'s prime minister, has announced that "liberty day" when pandemic-related restrictions are to be lifted, has been delayed by a month. The notion that next Monday, the longest day of the year, would be the moment when Britons could all put restrictions behind them turns out to be a Midsummer Night's Dream. The reason, unfortunately, is that Covid-19 cases have started to pick up once more, even as they come under control on the continent. Suddenly, the U.K. leads Europe in cases over the last seven days, as this chart from Commerzbank AG reveals, and is battling an increase in cases while there is an almost universal decreasing trend on the continent:  The reason is that Britain now hosts the delta variant. With a new and more infectious version of the virus in circulation, the U.K. has lost the advantage gained by its early and successful vaccine rollout, which has left the country closer to herd immunity than anywhere else in Europe (or the U.S.):  What is perhaps most surprising, viewed from the U.S., is that the English seem broadly supportive of continuing the restrictions, with one snap poll by YouGov finding 71% of people supporting the delay:  There is enough alarm at the prospect of the disease entrenching itself once more that the public seems prepared to put up with this, despite everything. The government's climbdown was well telegraphed, and so far seems to have had little impact on markets. But it is as well to remember that the pandemic reserves the right to surprise and to reverse fortunes. Meanwhile, Germany appears close to having the problem under control after a difficult winter. This is another chart from Commerzbank:  And in much better news, the horrific outbreak in India seems now to have come under control. These are daily new infections:  We can all be cheered by this. But for the purposes of risk management, it is worth looking at the number of sharp reversals on these different pandemic charts from around the world, and continuing to be cautious. Survival TipsI still have football on the brain. First, let's all be grateful that Christian Eriksen appears to have survived his on-pitch cardiac arrest. Second, let's also be grateful that we aren't David Marshall, the Scottish goalie who is probably going to spend the rest of his life watching replays of one of the most extraordinary goals ever scored in international competition. You can see Patrik Schick's strike, scored almost from his own half with his first touch of the ball, here. Goals come in many varieties. For a brilliant piece of instinctive opportunism, I don't think this one can be beaten. For sustained individual brilliance, there's a certain goal by the late Diego Maradona (matched for skill, on a less important occasion, by a 19-year-old Lionel Messi); and for team goals try these ones, a 24-pass masterpiece by Argentina in 2006, and the goal that climaxed Brazil's triumph in 1970. If only all of life could be as perfect as Pele's pass to Carlos Alberto….. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment