| If you're a Bloomberg Green subscriber and want to start getting the CityLab Daily newsletter, sign up here. If you're a Bloomberg CityLab subscriber and want to start getting our daily Green newsletter, sign up here. Building Higher, StrongerBy Amanda L Gordon It feels like a precipice moment for Palm Beach, a Florida town in the throes of a waterfront mansion-building mania just as the impacts of climate change start pushing in. At the town council's regular meeting this past week, officials talked about the need to raise the grade of a beloved bike trail—and, at the same time, somehow add height to the privately-owned seawalls running alongside it. Raising both together would help preserve views and accessibility. But if individual sections of the public bikeway and the mansion-fronting seawalls are raised piecemeal and go out of sync, it would weaken the defense against flooding and make for uneven pedaling. As the town's director of public works Paul Brazil put it, "We don't want our bike trail to become a mountain bike trail." The next day, at another meeting in the same room in Palm Beach Town Hall, some of the same cast of characters recalled the insurrection that took place years ago when the council got close to passing building-code reforms that would have regulated megamansions. Some moneyed locals got together, formed a political group and quashed the effort. Any rule that impacts waterfront properties on Palm Beach Island, particularly in neighborhoods like the North End with more modest homes, risks backlash that can seem more intense than any flood. "Code reform, it's like touching the third rail—you do that and you get electrocuted," said Lew Crampton, a member of the town council. And yet the message of this week's two meetings was clear: Palm Beach's planners and elected officials can't steer away from mansion politics forever. Flood risk is rising in tandem with the island's extraordinary real estate prices—and the boom, in turn, is what provides lavish tax revenue to spend on new coastal defenses to protect increasingly valuable megamansions. That dynamic is at the center of the feature story I wrote with Prashant Gopal for Bloomberg Green. Some local millionaires and billionaires say they aren't worried about protecting their homes for climate change risk, either because the worst of it will come too late (most people in Palm Beach are over 65) or because these are people with plenty of money to pick up and move somewhere safer. Still, there's nothing like a superheated waterfront housing market to create heightened awareness of all the ways the coasts are less safe than before. The houses in this boom are not only getting bigger and more expensive, they're also getting lifted higher above maximum-risk flood zones and getting outfitted with flood gates, frangible walls, and other bespoke defenses against extreme weather. The town has a responsibility to do its part for homeowners, which means weighing new rules to mandate resiliency while embracing public works to protect the public good and quality of life. As part of an effort by town staff to lean in to climate preparation, consultants from the Woods Hole Group have been hired to prepare detailed suggestions for addressing the island's vulnerabilities. The report is nearly final, although debates over implementation will likely have to wait until seasonal homeowners return later this year. Here's a sampling of the policy proposals: - Raising the seawalls higher. Defenses on Palm Beach's lakeside, along the more vulnerable intracoastal side of the island, will only be as strong as the lowest seawall or bulwark. But it's going to be difficult to get homeowners to raise them all at once. Woods Hole is proposing policy changes that will make homeowners raise the seawalls more often than under current rules. One sticking point may be the fact homeowners on the less-vulnerable ocean side of Palm Beach island have seen their beach nourished with local and federal funding for decades. There may be resistance to the idea intracoastal homeowners have to pay in full for their own protection, while nearby oceanfront owners don't.

- Building a surge barrier. The idea is to put up a moveable barrier wall on an inlet that's an active port, both for Steve Wynn's yacht and smaller fishing boats. The town couldn't take this on alone. The first step would be joining up with other municipalities to ask for an Army Corps of Engineers study backed by a congressional appropriation. Any barrier would take a long time and a lot of money.

- Lifting up the houses. Like seawalls, houses on the island have kept rising to remain above the level required by Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps. Exactly how to build higher is a matter for potential debate. Currently, builders use fill. But Palm Beach may eventually adopt techniques used in places like Charleston to leave an unoccupied, sacrificial first floor that can flood without damage. Building aesthetics and other neighborly considerations tend to hang over the matter. You can easily spot longtime Palm Beachers, whose homes haven't been renovated or lifted against floods, living next to redeveloped and uplifted megamansions.

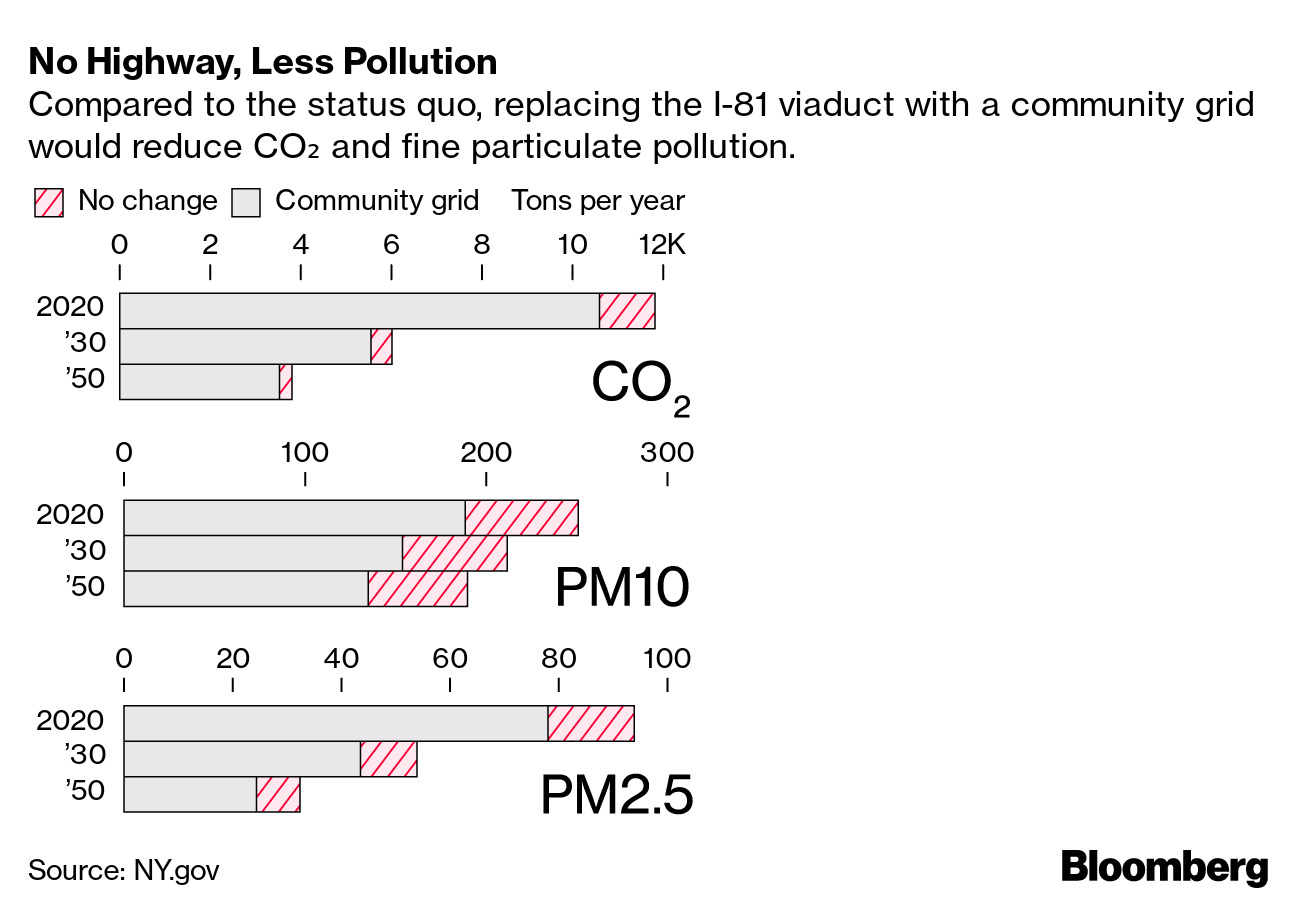

Paul Castro, a zoning official, said the code was written so that everybody who renovates or rebuilds has to go before the town to do anything different from what's prescribed—and just about everybody does so (with lawyers getting plenty of billable hours in the process). Changing what homeowners can do on the land they own, like mandating seawalls of equal heights, could encounter resistance. Palm Beach officials this week decided to seek an expert in code reform. They also discussed the urgency of managing relations with homeowners. Despite its deep pockets, the town currently has no public affairs officer. There's likely turmoil to come. For the rest of us who don't live in a waterfront mansion, it's going to be worth watching how this goes. Because Palm Beach is undergoing a process of adaptation that's going to play out again and again in the near future, along vulnerable coasts across the country. Like getting the Green Daily newsletter? Subscribe to Bloomberg.com for unlimited access to breaking news on climate and energy, data-driven reporting and graphics, Bloomberg Green magazine and more. Watch the future unfold. Wednesday, June 30 for Bloomberg New Economy Catalyst, a global 6-hour virtual event celebrating the innovators, dreamers, scientists, policymakers, and entrepreneurs accelerating solutions to today's greatest problems. The conversations will explore what matters, what's next, and the what-ifs in climate, agriculture, biotech, digital money, e-commerce, and space — all through the imaginations and stories of these ascendant leaders. Register here. Some other reads… Take a road trip from New York to California to see infrastructure projects with the potential to make cities more livable and equitable. It's a good time to think about reform: U.S. cities and states have rebounded from the pandemic faster than anticipated and are experiencing a double windfall of tax revenue and federal rescue aid. For example, a proposal to tear down the I-81viaduct through Syracuse and replace it with a community grid could reduce vehicle-miles traveled and emissions.  - A new office building near Berlin's Reichstag shows how climate protection has come to dominate the political narrative.

- Norway, the world's electric-car capital, is having nasty fights over oil.

- Intense heat and high humidity threaten the health and performance of athletes at the Tokyo Olympics.

|

Post a Comment