WarrantsA recurring theme of this column is that if you have the power to make the price of a financial asset go up, you should (1) do that but (2) buy a lot of it first. So for instance Tesla Inc. is a big company and its chief executive officer, Elon Musk, is a famous influential guy with a lot of Twitter followers. So when Tesla announced that it would start accepting Bitcoin as payment for its cars, the price of Bitcoin went up. This was very predictable. So what did Tesla do? It bought $1.5 billion of Bitcoin before announcing the news, and then Bitcoin went up and it had an immediate gain.[1] I am a simple man and to me this seems good. Buy a thing, create good news for the thing, announce that news, watch the price of the thing go up. In general I think it is under-utilized, as a strategy. You don't hear stories about, like, Moderna Inc. running a successful trial of its coronavirus vaccine and buying a ton of call options on cruise lines and airlines before announcing the news. That would have been a good trade! Of course one has to be careful. Insider trading laws are complicated, and you might worry that this trade — you buy the asset when you know your plans and the market doesn't — raises legal risks.[2] You might worry about market manipulation: If you do this trade, you want to make sure that you're doing something real to create economic value for the thing you're buying, not just saying "I like the stock" to get a short-term pop. There might even be antitrust concerns, where one company buys stock of another company to bet on the effects of the first company's actions. And even if it's all legal, it's potentially bad public relations, for reasons that are not fully intuitive to me. People seem to think that this trade is bad, because you know something that the market doesn't know, and you use it to make a profit. Whereas I think that this trade is good, because you know something that the market doesn't know, and you use it to make a profit. Amazon.com Inc. is a big company, and if it decides to partner with a smaller company it can steer a ton of revenue and attention to that smaller company. Amazon might reasonably think "we are sending all this revenue and attention to the smaller company, and they are going to profit from it, and we want to extract as much of that profit as possible for ourselves." One way to do that is to set the commercial terms to be as favorable as possible to Amazon — pay suppliers as little as possible, etc. — but arguably a better way to do it is to (1) cheerfully create value for the smaller company but (2) buy some of that company first.[3] You bestow Amazon's blessing on other companies, this blessing makes those companies more valuable, and your stake in them benefits from your actions. So: The technology-and-retail giant has struck at least a dozen deals with publicly traded companies in which it gets rights, called warrants, to buy the vendors' stock in the future at what could be below-market prices, according to corporate filings and interviews with people involved with the deals. Amazon over the past decade also has done more than 75 such deals with privately held companies, according to a person familiar with the matter. In all, the tech titan's stakes and potential stakes amount to billions of dollars across companies that provide everything from call-center services to natural gas, and in some cases position Amazon among the top shareholders in those businesses. The unusual arrangements offer another window into how Amazon uses its market heft to increase its wealth and clout. The company has been under growing scrutiny from regulators and lawmakers over its competitive practices, including with companies it partners with. While the deals can benefit the suppliers by locking in big contracts, which can also boost their share prices, executives at several of the companies said they felt they couldn't refuse Amazon's push for the right to buy the stock without risking a major contract. The deals in some cases also give Amazon rights such as board representation and the ability to top any acquisition offers from other companies. For Amazon, the arrangements give it a piece of the potential upside their vendors can get from doing business with one of the world's biggest companies.

For instance: Grocery distributor SpartanNash Co. last year amended a contract with Amazon to deliver groceries to its Amazon Fresh arm. The Grand Rapids, Mich.-based company had been supplying Amazon with food since 2016, but this time Amazon added a condition: if it bought $8 billion worth of groceries over seven years, it could get warrants to purchase around 15% of SpartanNash's stock at a price potentially lower than the market. Amazon also said it wanted to be notified of any takeover offers for SpartanNash and have a 10-day window to offer a counterbid. SpartanNash executives were taken aback, said people familiar with the matter. No customer had requested such terms before. Executives ultimately decided they didn't want to haggle with one of SpartanNash's biggest customers, and that being tied to Amazon could raise their company's profile, one of the people said.

Well, look, here is a graph of SpartanNash's stock price over the last year:  Can you spot the day that SpartanNash announced its Amazon contract? I bet you can! The stock was up 26.3% that day. SpartanNash added 26.3% to its equity market value, in exchange for giving as much as 15% of its equity market value to Amazon. Twenty-six is more than 15.[4] Seems like a good trade for both of them? Obviously SpartanNash would have preferred to add 26.3% to its market cap without giving any of it to Amazon, but that deal wasn't on the table. Also it is quite possible that what "raised their company's profile" is not just the commercial agreement but also the warrants, that being part-owned by Amazon made it more valuable than merely being an Amazon supplier would. Amazon's reasoning seems to be explicitly about capturing the upside that it creates in smaller companies: Amazon's first major warrants deal with a publicly traded vendor came in 2016. Amazon was seeking a partner with cargo planes to help build out its massive logistics network. Executives reasoned that the company's potential partners were all smaller, lesser-known companies with stagnant growth, and that a major contract from Amazon would invigorate their stocks, according to a person familiar with the matter. Amazon wanted some of that potential upside, the person said.

That reasoning strikes me as completely correct and kind of obvious. Yet somehow this approach is not popular; it is viewed as grasping and excessive and monopolistic. And I suppose Amazon's competitive advantage is in part that it does the economically obvious thing even if that seems grasping and excessive and monopolistic. Oh one other very niche thing that I enjoyed is that Amazon's warrants appear to be based on the U.S. Treasury's Troubled Asset Relief Program warrants: Former Amazon executives who worked on warrant deals said they found no direct precedent before the company began striking them. For a guide, an Amazon team sleuthed through financial documents from the 2008 financial crisis to find information about bank bailouts that involved warrants, one of the people said.

I used to (very) occasionally create warrants, as an equity-linked investment banker, and I will say that "just copy the TARP warrants" was kind of the standard approach. Arguably Treasury, in turn, was influenced by Berkshire Hathaway Inc.'s preferred-stock-plus-warrants investment in Goldman Sachs Group Inc. a few weeks before the TARP deals, and the Berkshire deal is also a popular precedent. These are good examples of my general rule, that if you can create a ton of value for another company you should buy its stock first. Warren Buffett, famously, provides a halo of folksy value-investing goodness to the companies he supports; buying warrants from Goldman let him monetize that halo. And when the U.S. government stepped in to support the big banks in the fall of 2008, it was sending a strong signal to the effect of "unlike Lehman, we're not going to let the banks that take TARP money go under." Good for the stock price! Might as well get some warrants for that. BignessSome banks are very big. Some people think this is bad. There is a traditional way to say "it is bad that this company is so big," and that way uses the word "monopoly." "This company is so big that it is a monopoly, which is bad." It is useful to be able to say this, because the government has a lot of power to limit monopolies, to regulate their behavior and break them up. It is not, however, particularly true of the big banks. A monopoly is a specific thing, a company that is so big that it dominates its market and can force out competitors and raise prices. The markets in which banks compete are, for the most part, extremely competitive.[5] If you want a mortgage, you pretty much pay the market rate for mortgages; JPMorgan Chase & Co. can't charge you whatever it wants. Still, people think it is bad that the banks are so big, for other reasons. They worry about risk concentration, about banks that are "too big to fail" taking too many risks and the taxpayers bearing those risks, about too much centralization of banking making it more fragile, about banks that are "too big to manage" doing dumb things and crashing the financial system. Those worries are controversial, but never mind that. Assume for now that they are correct. What should the government do about them? One possibility is that the government's antitrust regulators — at the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission — should go after the biggest banks for antitrust violations. The regulators could say "you are too big, you are a monopoly, we need to break you up into smaller pieces." And then the banks would say "no," and they would go to court, and the regulators could try to prove that the big banks are monopolists. And this would be hard to do, because they basically aren't. It wouldn't be impossible, though, I guess, because they are in lots of businesses and some of them are less competitive than others and there are probably some bad emails somewhere and so forth. The regulators' odds of breaking up the big banks on antitrust grounds wouldn't be zero. But they would be low. The other possibility is that other government regulators should, in setting other regulations, take bigness into account and try to regulate and discourage it. Conveniently banking is a very regulated business, and there are regulators and prudential supervisors who can do all sorts of meddling in a bank's business. So for instance if you worried that giant banks could be "too big to fail" and pose a systemic risk to the financial system, the banks' capital regulators could put out a rule saying "very big banks need to have more capital to offset the higher risk they pose to the financial system." That would both reduce the risk of big-bank failure and also create an incentive for banks to stay smaller or break themselves up. And in fact there is such a rule, for exactly those sorts of reasons; it is called the "G-SIB surcharge." Or if you worried that giant banks could be "too big to manage" and do dumb things, then the banks' supervisors could tell a big bank that did a dumb thing "you can't get any bigger until we're satisfied you won't do more dumb things." They can just do that! The supervisors can just tell a bank not to get bigger, and it has to listen! They actually did it to Wells Fargo & Co., it's kind of amazing. The theory wasn't "Wells Fargo is a monopoly"; it was just "we don't like what Wells Fargo has been up to so it can't get any bigger." I should emphasize that banking is a very regulated business, and the government doesn't have quite as many levers to pull with most other businesses. Still lots of businesses are regulated in lots of ways, and the same general principles apply: - If you think it is bad that a business is big, because it has a monopoly, sure, have the antitrust regulators go after it for antitrust violations.

- If you think it is bad that a business is big, for other reasons, have other regulators try to limit its bigness in ways that directly address those other reasons.

- In a pinch, if you think it is bad that a business is big, you could always have the other regulators try to limit its bigness in ways that don't relate in any particularly logical way to those reasons. If you think that the bigness of social media companies is bad because they spread misinformation and undermine democracy, that is not really an antitrust problem,[6] and there is not exactly a Federal Truth Regulator that can promulgate misinformation rules. But maybe you can find some regulatory regime to shoehorn into that purpose. Maybe you've got a regulator in charge of, I don't know, internet bandwidth or wireless spectrum or electricity usage or truth in advertising or whatever,[7] and you tell that regulator to turn up the heat on big social media companies. Not because you care about their electricity usage or whatever, but just to deter them from being big, because you think their bigness is bad.

- If all else fails, you can have the antitrust regulators try to break up the business because it is too big, even though it isn't a monopoly. That may not work though.

We talked yesterday about Facebook Inc. Lots of people think it is bad that Facebook is so big, but it is a little hard to put that in traditional monopoly terms. Is the problem of Facebook's bigness that it can charge users monopolistically high prices for posting on Facebook? No; posting on Facebook is free. Is the problem that it can charge advertisers monopolistically high prices for advertising on Facebook? No. I don't know if it can; I just know that I have never heard anyone make that complaint: If you don't like Facebook, it's not because you worry about advertisers overpaying. Is the problem of Facebook's bigness some other form of anticompetitive behavior that makes consumers (Facebook users) worse off? Sure, maybe; intuitively I suspect Instagram would be a nicer place if it was still independent than it is under Facebook's ownership. But this stuff is a little hard to articulate, which is why the FTC failed to articulate it: It sued Facebook for antitrust violations, and this week a judge dismissed that lawsuit for failing to even say why Facebook might have a monopoly. "It is almost as if the agency expects the Court to simply nod to the conventional wisdom that Facebook is a monopolist," wrote the judge. The conventional wisdom is that it is bad that Facebook is so big! But that does not make it a monopoly in the technical, legal sense of the term. I suspect the main problem most people have with Facebook's bigness is not about consumer choice but rather about Facebook's political and social influence. You could imagine addressing that more directly than with antitrust law. And there have been suggestions for doing so — repealing Section 230, using election law to regulate Facebook, etc. — though I can't say any of them strike me as great. Still it's the right basic idea. Figure out what you don't like about Facebook's dominance and then regulate that, rather than just equating bigness with antitrust. Anyway here's this: The Biden administration is developing an executive order directing agencies to strengthen oversight of industries that they perceive to be dominated by a small number of companies, a wide-ranging attempt to rein in big business power across the economy, according to people familiar with the plans. The executive order, which President Biden could sign as soon as next week, would direct regulators of industries from airlines to agriculture to rethink their rule-making process to inject more competition and to give consumers, workers and suppliers more rights to challenge large producers. The goal is to broaden the way policy makers approach business concentration in the U.S., going beyond conventional antitrust enforcement focused on blocking big mergers. For example, companies in industries controlled by a small number of big firms might face new rules for disclosing fees to consumers or for their relationships with suppliers, the people familiar with the effort said.

Seems right! Or not, I mean; I guess it depends on how you feel about big business generally. But if you feel bad about some big business specifically, addressing that in a specific way — rather than assuming that big business is exclusively an antitrust problem — seems like the way to go. Speaking of antitrust This is from last week but we didn't talk about it then and it's interesting: U.S. investigators who focus on corporate collusion are examining how global banks handled multibillion-dollar trades with Archegos Capital Management that sent stocks into a spiral and burned other shareholders. The Justice Department's antitrust division is handling at least part of the probe into the collapse of Bill Hwang's firm after lenders rushed to liquidate souring positions in March, according to people familiar with the matter. The debacle also erased much of the billionaire owner's fortune and saddled banks with more than $10 billion in losses. The division has been seeking information from Hwang's biggest backers on Wall Street, who had discussed the possibility of moving in concert to unwind the portfolio and sever ties with his busted family office, the people said, asking not to be identified because they aren't authorized to discuss the inquiries. ... At the root of the collapse were Archegos's massive bets on certain stocks, such as media companies ViacomCBS Inc. and Discovery Inc., as well as Chinese tech darling Baidu Inc. Banks provided billions of dollars in leverage, eager to reap fees handling the investment firm's burgeoning portfolio. But as the positions started to sour, Archegos was unable to meet margin calls, and bankers soon realized the extent to which it had placed parallel positions with competitors.

The stylized popular story of Archegos is that it had enormous levered stock positions with half a dozen big banks, but because it did those trades via swaps, nobody knew about it. Each bank thought "we own a lot of stock for these Archegos guys huh," but no bank knew that a bunch of other banks also owned a lot of stock for Archegos. Then one day some of the stocks went down, the banks asked Archegos to post more money, and Archegos replied "nope, we're fresh out of money, also by the way we've got these same huge positions on with a bunch of other banks, okay, have fun with that, bye!" And then the banks called the other banks and were like "wait were you lending Archegos billions of dollars to buy ViacomCBS and Discovery?" and the other banks were like "yes, wait, were you lending Archegos billions of dollars to buy ViacomCBS and Discovery?" And they realized they had a problem, which was that they all owned billions of dollars of ViacomCBS and Discovery that they didn't want, and that the prices of those stocks had been pushed up to irrational levels by Archegos buying all of them. And so the banks got together and said, look, we could all sell these stocks that we don't want now, but that will push their prices way down and we will all lose a ton of money. Or we could wait and sell them over time, rather than dumping them in a fire sale, and the result will be that markets will be more orderly and rational and also we won't lose so much money. But we have to all agree to do that together, because if most of us wait but some of us sell early, the ones who sell early will do well but the rest of us will be hosed. And Goldman Sachs heard "the ones who sell early will do well but the rest of us will be hosed," and its ears perked up, because Goldman loves (1) doing well and (2) hosing its competitors, so Goldman dumped its Archegos-linked stocks and did well, and the coordination broke up and everyone ended up dumping their stocks in a fire sale that crashed the market for those stocks and generally freaked out the market. I don't know how accurate this narrative is in its details but it seems to be the conventional wisdom about Archegos. In particular, the part about all the banks getting on the phone to discuss not selling stock to keep the prices high is very much a part of the story. Here is Bloomberg's story from March: Global investment banks, gathering in a hastily arranged call, needed a swift truce to deal with Bill Hwang's Archegos Capital Management if they were to head off billions of dollars in losses for banks and a potential chain reaction across markets. Yet by Friday, it was everyone for themselves. ... Emissaries from several of the world's biggest prime brokerages tried to head off the chaos by holding a call with Hwang before the drama spilled into public view Friday morning. The idea, pushed by Credit Suisse, was to reach some sort of temporary standstill to figure out how to untie positions without sparking panic, the people said. ... Soon came the finger-pointing over who was breaking ranks, the people said. Some emerged from the talks suspicious that Credit Suisse wasn't fully committing to freezing sales. By early Friday, rival banks were taking umbrage after hearing that Goldman planned to sell some positions, ostensibly to assist Archegos. Morgan Stanley began drawing public attention with block trades.

And the point I want to make here is that if a bunch of competitors get together on a conference call and agree to limit the supply of some product in order to keep the price of that product high, that is absolutely a core antitrust violation! That's the main bad thing! You can't do that! Everything in those last three paragraphs sounds super illegal, if you think of it as, like, chicken producers trying to reach an agreement not to sell too much chicken to keep the price of chicken up, and then "finger-pointing over who was breaking ranks" when one of them sold more chicken. Don't get me wrong, I sympathize with the banks. They really were hoping to "head off the chaos," and they failed, and it was chaos, and that chaos was bad and sparked a bunch of investigations. (Also, to be clear, a lot of facts have not come out, the banks have good lawyers, and it is entirely possible that the way this all happened was perfectly legal, not collusion among banks about selling stock but rather negotiations between the banks and Archegos about the collateral terms of its swaps.) In general if some cartel of producers colludes to keep supply low and prices high, they will say "we just want the market to be orderly," and no one will sympathize with them. But in financial markets that is much more of a thing: Low volatility is sort of a social good, and frankly high prices are popular. If the price of chicken goes down, most people are happy (not chicken farmers); if the price of stocks goes down, most people are sad. When the banks dumped all their Archegos-linked stocks at fire-sale prices, the general reaction was that that was bad. You can understand why they wanted to avoid that. So when I read that Bloomberg story back in March, and I saw phrases like "needed a swift truce … to head off billions of dollars in losses for banks and a potential chain reaction across markets" and "head off the chaos" and "untie positions without sparking panic," I was like, yes, right, those are good things and I see why the banks tried to do them. Honestly it did not even occur to me that they might create an antitrust problem. But I guess it did occur to the Justice Department's antitrust division. Financial literacyImagine being the Securities and Exchange Commission lawyer who wrote this description: One of the PSC's 15-second TV spots shows an investor realizing the benefits of a diversified portfolio, saying, "I had no idea it was that easy to diversify my portfolio." Once the concept is realized, balloons drop into the scene to help the investors celebrate their new investing knowledge. The other TV spot shows an investor learning about compound interest and the possible financial gains of regularly contributing to investments. saying, "I had no idea investing regularly could add up this much." As soon as the concept sinks in, cheerleaders pop into the scene to help the investor celebrate her investing knowledge.

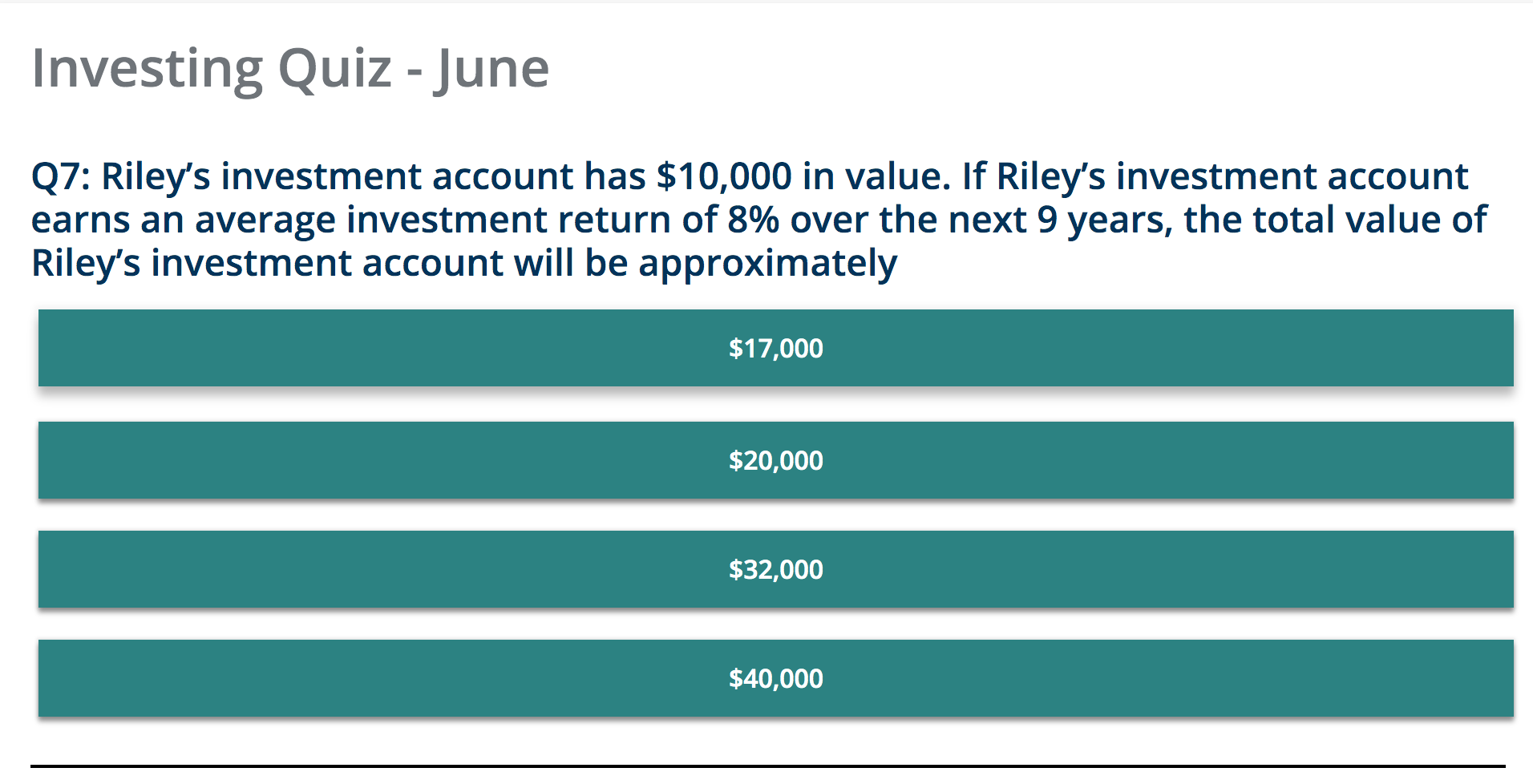

Those are real ads! For the … Securities and Exchange Commission? I guess for Investor.gov, its investor-education website. You can watch the ads here, though I should warn you that I watched them like two days ago and am still hunched over in a cringing posture. These ads pack a lot of embarrassment into 15 seconds. The quote above is from this SEC press release, "New SEC Public Service Campaign: Investing Regularly Really Adds Up." I suppose the SEC dropping balloons to celebrate diversification is a reasonable antidote to Robinhood dropping confetti to celebrate YOLOing your life savings on GameStop options? There is lots of other stuff in the SEC campaign. For instance, "As part of the campaign, investors can also test their investing knowledge with a new quiz that will be published each month on Investor.gov/quiz." The quiz expects you to know the rule of 72:  Nine years is sort of a weirdly specific period, but eight times nine is 72. I have often been skeptical of the popular theory that financial literacy consists mostly of knowing about compound interest. I do wonder though, like, if you surveyed a bunch of people and asked them two questions: - Have you fallen for a Ponzi scheme, and

- Do you know the rule of 72?

then my guess is that people who know the rule of 72 are less likely to have fallen for Ponzis than people who don't? But that is a wild guess and I could see how your intuition might go the other way. A very little knowledge is a dangerous thing. Things happenThe Fall of the Billionaire Gucci Master. Banks turn to blockchains to reform costly bond market. Global Regulators Try Again to Eliminate Money-Market Hazards. Jamie Dimon Says Paris Is JPMorgan's New EU Trading Hub. Barclays Moves Traders to London Headquarters in Office Shake-Up. Credit Suisse Weighs Overhaul of Wealth Management Business. New Jersey Attorney General Chosen as SEC Enforcement Director. The chief executive of Teneo, an influential advisory firm, steps down. Germany Thwarts Cyberattack, Denies Impact on Banking System. How a SoftBank-Backed Construction Startup Burned Through $3 Billion. Sam Altman Wants to Scan Your Eyeball in Exchange for Cryptocurrency. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] Later Tesla announced that it would *stop* accepting Bitcoin as payment for its cars, and the price of Bitcoin went down. Arguably Tesla should have *sold* all of its Bitcoins before making that announcement, though that is a rather advanced move. [2] In the general case I think it does not, at least under U.S. law, but you do want to consult a lawyer and be careful. I think for instance that it would be fine for Moderna to buy call options on airlines, but perhaps a bit icky for a Moderna *executive* to do it in her personal account. And many non-U.S. legal systems have stricter level-playing-field-type insider-trading regimes that would make it harder. [3] This is arguably better than gouging them on other terms because it aligns incentives: They will want to do more business with Amazon because the economic terms of any particular transaction will be reasonable and competitive (and Amazon's extra edge over other potential counterparties comes in the form of warrants, which are a sunk cost), while Amazon will want to do more business with them because it makes money from the warrants. [4] In fact the warrants are not struck at zero — they're struck at roughly the market price before the deal was announced — so SpartanNash wasn't even "giving" Amazon that 15% stake; Amazon still has to pay for it. [5] Some are not, and there are occasional antitrust rumblings there. It's weird that the standard fee for a smallish initial public offering is 7%, fine, and every so often the Justice Department will ponder that. Prices in the treasury market? Chat rooms sharing customer information in foreign exchange trading? The Archegos thing in the next section? [6] As classically understood. I think some people would argue that it is, or should be, and you could imagine a legal theory that it is. It is not, like, core antitrust though. [7] Or securities law, there's always securities law, everything is securities fraud. |

Post a Comment