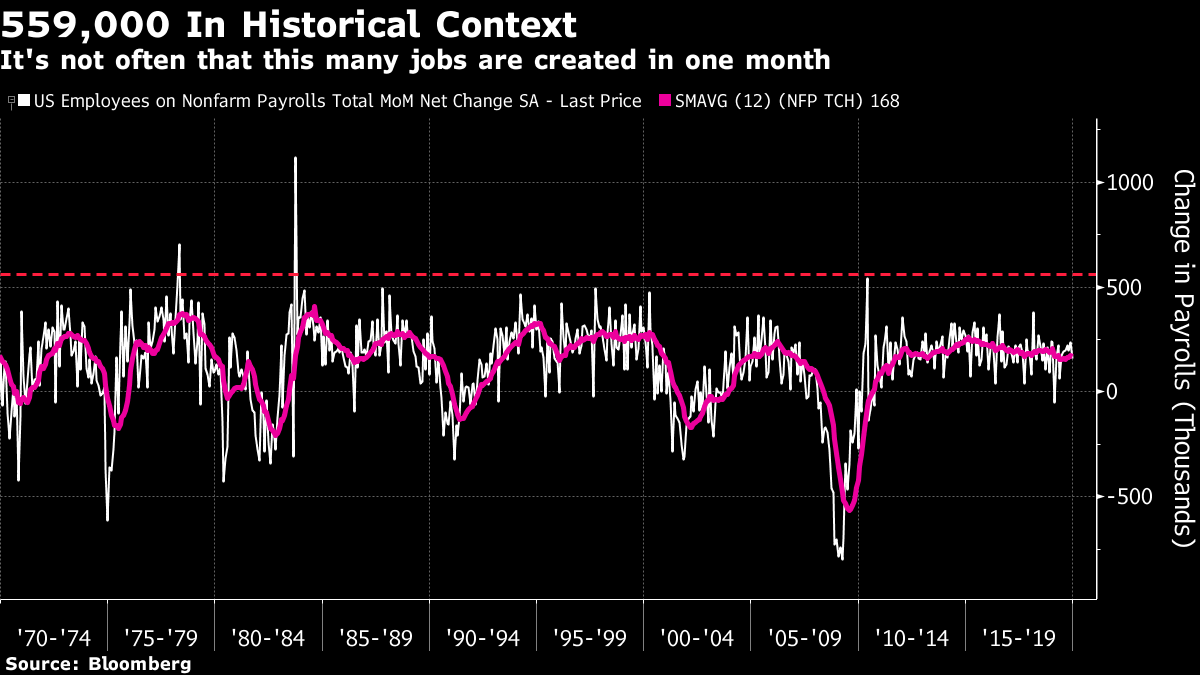

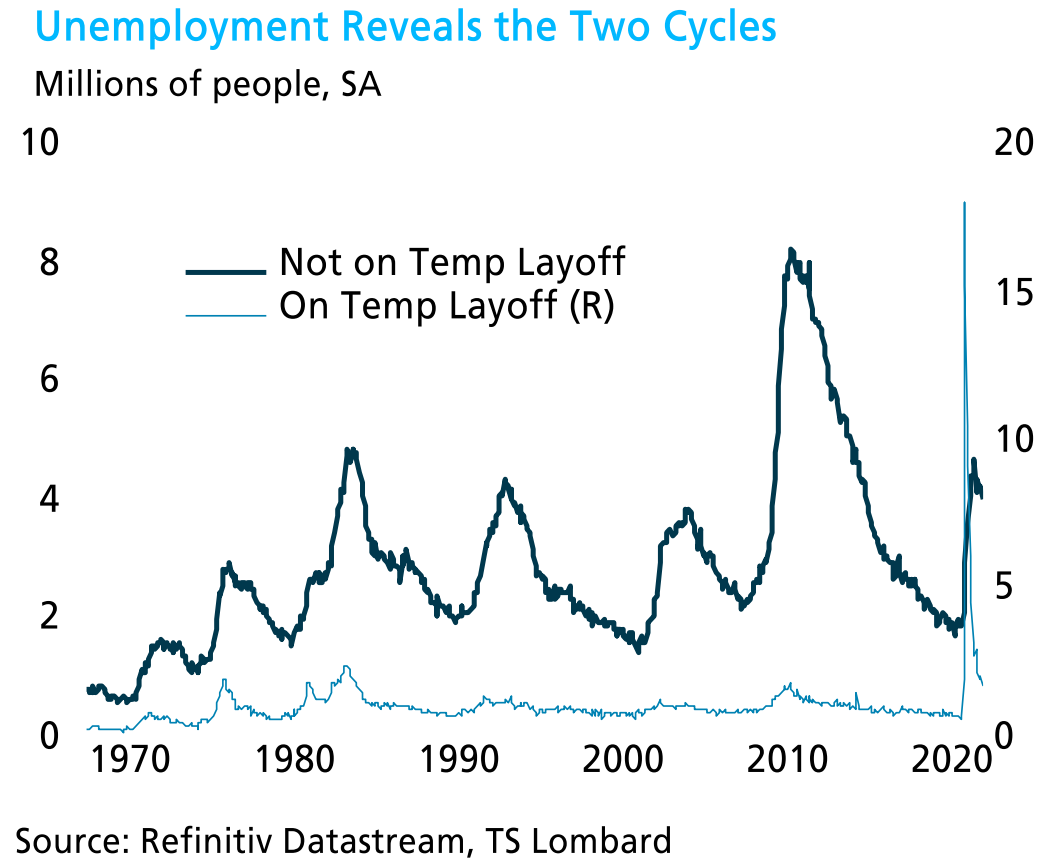

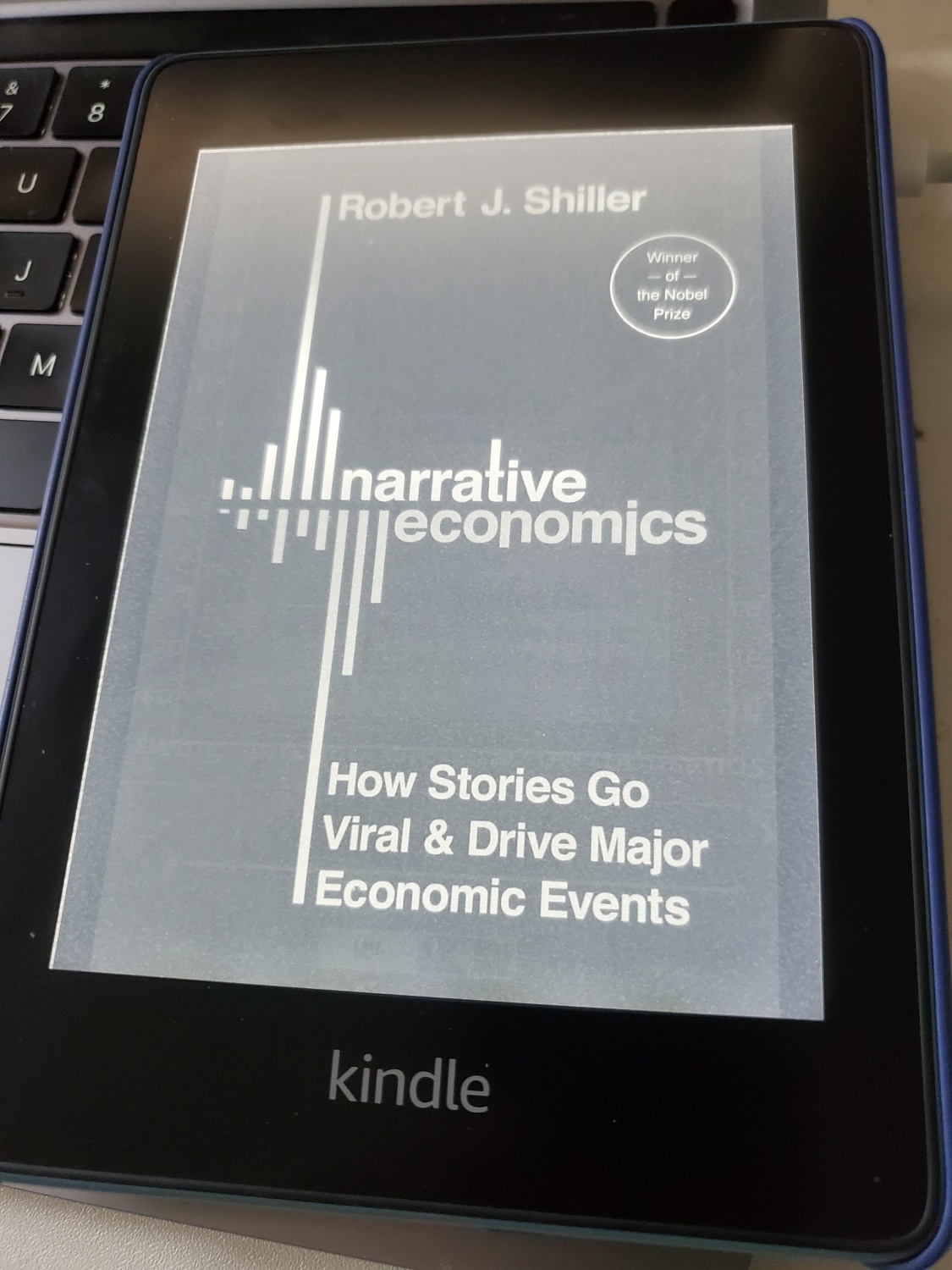

| Friday brought us a fresh bulletin from the U.S. labor market. The key question: What's the story? This is a confusing situation as the economy continues to adjust to last year's pandemic shock. There are a number of ways to describe the data we received last week. The important thing is the story we choose to tell about it. That in turn will have a huge impact on exactly how the economy responds over the months ahead; the stories we tell ourselves can have self-fulfilling consequences. So, the positive spin on the data announced at the end of last week is that the U.S. created 559,000 new jobs during May. Over the 50 years to the end of 2019, there were only two months that saw more jobs created than this. The horizontal line is fixed at 559,000:  On the face of it, this was a great month, then. But it was somewhat worse than expectations, always a problem. The trouble is where we started. There are many ways to measure unemployment; the one that increasingly preoccupies policymakers (with some reason), is the one that makes joblessness look worst: U6. Other jobless rates take employment as a proportion of the workforce, defined as those making themselves available for work. The U6 measure takes the total level of employment as a proportion of the total working age population. This number rose in the decades after the war as women entered the workforce. But it peaked in 2000, and set progressive new lows in the two recessions that followed. Measured this way, the story of what happened last year looks like some kind of biblical catastrophe. Even after the swift rebound, U.S. employment has still only clawed its way back to a level it last touched (other than during the Covid shutdown) in 1983. If this is the best gauge of the true social pain caused by joblessness, and there's a good argument that it is, then the story now is that the recovery is nowhere near fast enough. If policymakers want to heal some of the wounds and anger of the last two decades (and they do), then there is a need for years more of policy deliberately aimed at raising employment:  For a subtler way to look at it, try the following ingenious take from Steve Blitz, chief U.S. economist for TS Lombard. This shows the numbers on temporary layoff, which was obviously at an exceptional high last year, and the unemployment rate excluding these furloughs. Beyond the cacophony of the Covid retrenchments, and the extraordinary speed of the fall and snap back in employment, a more orthodox recession is now becoming visible:  On this basis, it looks like the worst is in, and the underlying recovery has just begun. That in turn implies that there is no longer any need for extreme emergency policies, and so Blitz suggests that we could see an announcement of a taper (the beginning of a reduction in the amount of asset purchases the Fed makes each month to bolster the market) as early as its meeting at the end of July. It's certainly possible to discern subtle shifts in rhetoric to allow the Fed to make what on the face of it would be quite a volte-face. And the weekend also saw a very heavy-handed hint from Janet Yellen, the last Fed chairwoman and now the Treasury secretary, when she said that higher interest rates would be a "plus" for the U.S. and the Fed. A comment like that is hard to ignore. But central banks need to be taken seriously, and cannot afford to lose credibility. While I think Blitz's analysis needs to be given weight, therefore, and while Yellen certainly cannot be ignored, I suspect two other narratives may prove more important. First is the "under-employment" narrative pictured in the second chart. The Fed, and the Biden administration, don't want to be seen as ducking the challenge of dealing with chronic underemployment. If they have meant what they have said so far, they are determined to change the paradigm, and convince us all that they are prepared to let inflation rise as they battle unemployment. The second narrative is the "Powell pivot." In 2018, the Fed started steadily shrinking its balance sheet, and tried to get the message out that it would continue to do this on "auto-pilot" without even regarding this as something that had to do with monetary policy. The market responded with a panicked selloff, and the Fed backed down. Neither Jerome Powell himself nor anyone else at the Fed will want to be accused of two pivots in one term. My best guess is that the Fed goes for it and risks inflation. Judging by Friday's action, which saw bond yields fall and stocks rise close to their all-time high from a few weeks ago, that is also the story markets are running on. Asian trading Monday, at the time of writing, doesn't yet suggest that Yellen's comments have significantly changed that story. We still have plenty of installments to look forward to. This week, it is another month's worth of inflation data, coming out on Thursday. And next week, the Federal Open Market Committee meets, and will likely have to admit at least to thinking about thinking about tapering. Narrative Fallacy?All of this was by way of discussing how we should probably best analyze markets and economics through narratives. We understand much of the world around us through stories, rather than numbers, and that applies even to economics.  That is the central thesis of this month's Bloomberg book club selection, Narrative Economics by the Nobel laureate Robert Shiller. He will be discussing his book on a live blog on the Bloomberg terminal on Tuesday, starting at 10 a.m. New York time. I will be joining him for the discussion, along with Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts, who has done much work on social mood and applying narratives to markets, and Christine Harper, the editor of the Bloomberg Markets magazine. You can follow along live by going to TLIV <GO> on the terminal. It should be well worth joining, even if you haven't had a chance to read the book. If you don't have terminal access, you can still ask questions in advance, by sending them to the book club email (not the best way to get hold of me usually) which is: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. Finally, for a lengthy and fascinating, but also critical take on Narrative Economics, I recommend this review in the New York Review of Books by former Bloomberg Opinion colleague Cass Sunstein. It even brings in some stories from Star Trek. WFHF (Working From Home Forever)In New York, life continues to return to normal. The Bloomberg office is now about a third full most days, all the special barriers that had been put up to discourage people from mingling have been removed, and there is a sense of office bustle once more. The legendary chance conversations around the water cooler are happening again. However, the shift toward home as a work base may still in some ways be permanent. Thanks to a great recommendation from Cardiff Garcia, my former colleague and now an independent podcaster, I offer this fascinating video presentation from Stanford academic Nick Bloom, who argues that the gains of working from home will prove permanent, even if many of us will be spending more time in the office. This is because: - There is now far less stigma attached to working from home. If you have a streaming cold and call in sick, your colleagues from now on will respect you for being so considerate, and you will get on with your work. And so on. Many of us find that we aren't so productive away from the workplace; but the great majority have still found it much more possible to get work done at home than we had thought.

- We've already spent the money. The upgraded routers and faster internet services that many of us grudgingly paid for during the pandemic are now fixed costs. That is one barrier removed. The same is true of ergonomic chairs, adjustable desks, and gleaming new monitors. Sometimes, we spent this money ourselves. Sometimes it was our employers (thanks for the monitor, Bloomberg). Either way, there is a psychological desire to make the most of sunk costs.

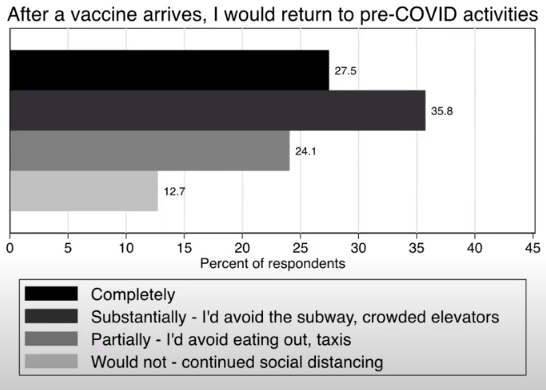

- A certain fear of working in proximity to other people will live on. I suspect the poll figures cited by Bloom in the chart below may be a little exaggerated. Some of us never had any anxiety about mixing with people in the first place (and were over-confident). Others are unduly lacking in confidence, and will still be nervous. The high numbers who say they would continue to alter their behavior will come down, but they will take time to do so. Beyond the workplace, that means concern about traveling in public transport for many commuters — and here such concerns do seem more reasonable. The next time there is a new flu strain around, we all now know the drill. The chances are that a lot of people will err on the side of caution, which means more working from home.

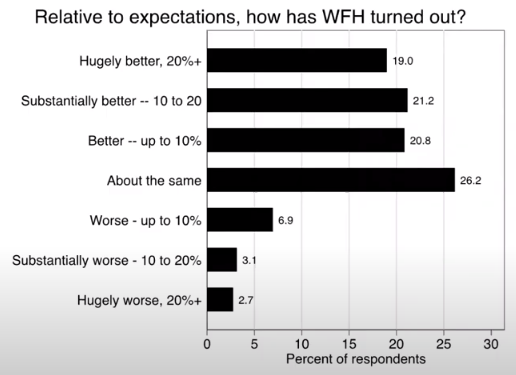

- Working from home has been better than expected. Personally, I think this can be overstated. The effect on productivity is undeniable, even if it's been pleasant to discover that the home is a viable workplace. But the results are in, and most people have been surprised by how easy it is:

Put all of this together, and it is a strong case for a lasting change in the way we work, even if it doesn't mean the death knell of the office. (Personally, I am enjoying being back, and more or less all my colleagues seem to feel similarly. But maybe that will wear off once the novelty has gone.) All of this will create opportunities. Changes in real estate markets at the margin could be profound, particularly for commercial space. The investment winners and losers of the next few years are going to need to work out exactly who wins most from the changes under way. Survival TipsYes, it does feel good to go back to the ballgame. As trailed last week, I spent Saturday night in the sticky heat of the Bronx, watching the Boston Red Sox beat the New York Yankees 7-3, and it was great fun. By the end of the weekend, the Red Sox had swept all three games of a series in New York for the first time in a decade, which was even more fun, as far as I'm concerned. But what was most interesting, with some restrictions still in force and the stadium still not full, was a distinct shift in the atmosphere. The Red Sox-Yankees rivalry isn't as nasty as, for example, the Celtic-Rangers rivalry in Glasgow, which is based on religion, or the contest between Real Madrid and Barcelona, which still derives much of its passion from the Spanish Civil War. But in general it is a real and heated rivalry. Fans of the winning team really enjoy sticking it to the losers. And when the home team does badly, which doesn't happen often to the Yankees, you can expect their own fans to be remorseless in making themselves heard. What was interesting about this game is that everyone, even the hardened types who go to watch baseball in the Bronx, was happy just to be there. People in Yankees and Red Sox gear were standing together and sharing jokes, and there were plenty of high fives from people in Yankee caps for those of us in Boston colors as we were leaving. People enjoy sport, and after the last year, they enjoy experiencing it with people with whom they normally disagree. The European soccer championships start this week. Then there are the Olympics to look forward to. The quickest look at Twitter shows there's a lot of anger and distrust in the world. Sport might just bring us together. George Orwell famously disagreed, and said that sport was just "war minus the shooting" (it's a great essay if you haven't read it). But let's think positive; there could be glory days ahead. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment