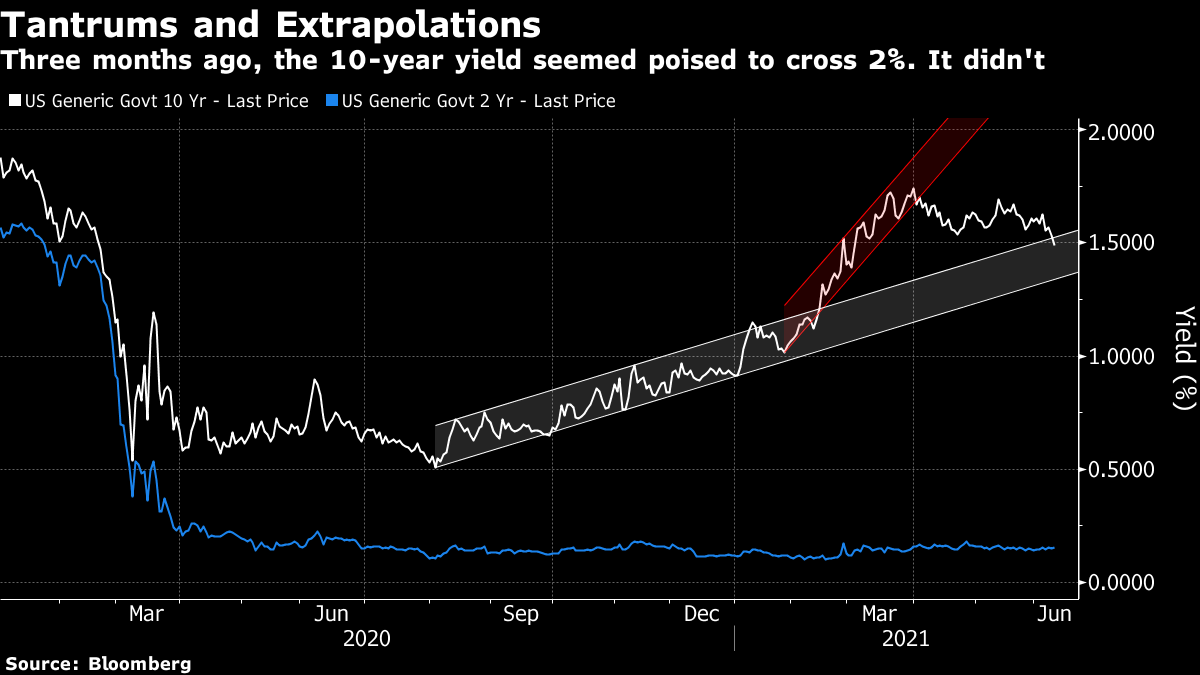

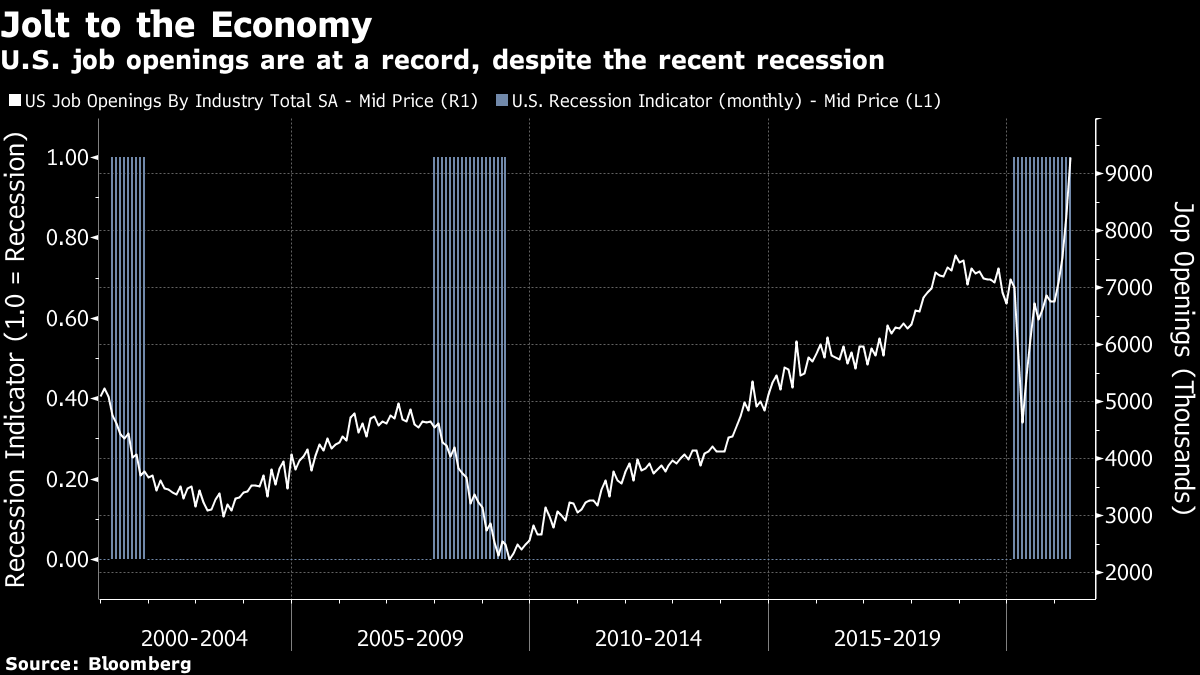

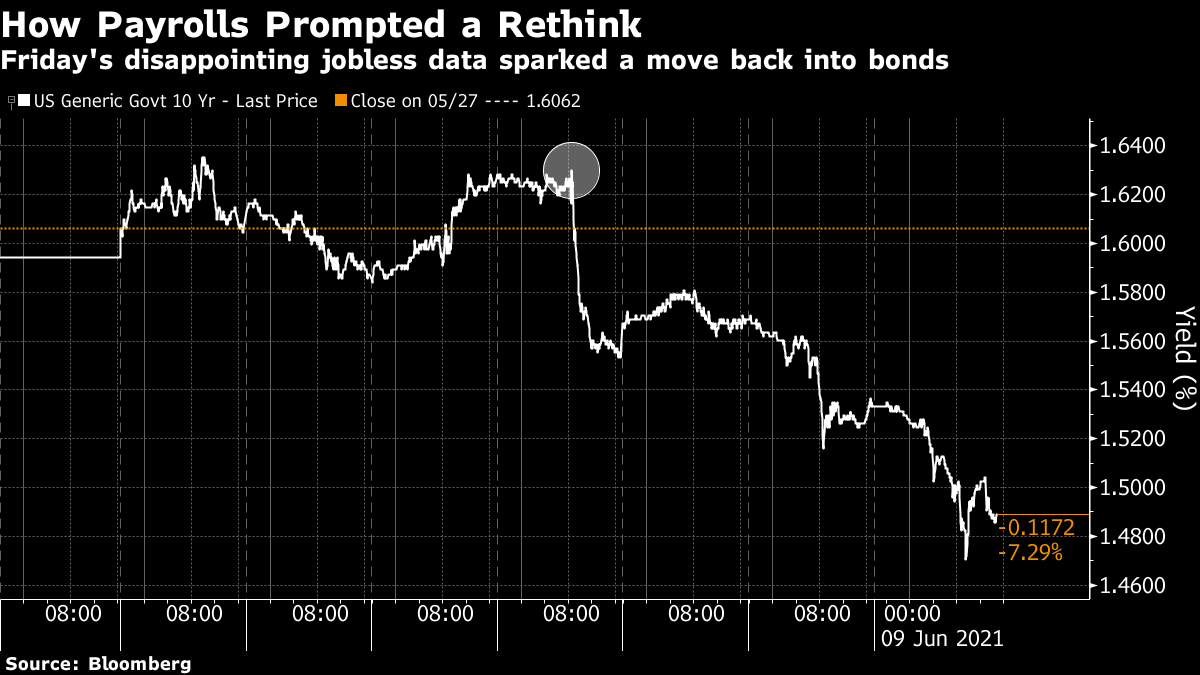

Cold FeetSuper Thursday is with us. In the next few hours, we will find out how the European Central Bank intends to adjust monetary policy as Europe finally brings the pandemic under control, and we will also get to see whether the startling jump in April's U.S. inflation numbers persisted or even accelerated in May. A lot hinges on this. And yet markets have behaved as though the outcome of these events were already known. There has been a sharp move away from bets on inflation. The fall in the benchmark 10-year yield since it peaked two months ago has now been equivalent to a rate cut by the Federal Reserve, and Wednesday saw it drop below 1.5% for the first time since March. With two-year yields staying almost unchanged, this means that the yield curve has flattened in the last three months. That this seems shocking owes much to the human tendency to extrapolate existing trends into the future, and also the market's tendency to stage "tantrums" in which yields rise in a hurry as bond investors (once known as "vigilantes') storm out. As marked on the chart, the 10-year yield appeared to follow a clear trend from last summer until this spring. Then, in February and March, there was a vintage tantrum. Yields shot up, and suddenly predictions that they would rise above 2% in short order were popular. Very few at that point would have predicted that the market would revisit 1.5% before a trip to 2%. But that is what has happened:  Why such a reassessment, shortly before what could be very significant news on inflation? It isn't because of any clear and obvious evidence that we don't need to worry after all. U.S. data so far this week have generally added to evidence of mounting inflationary pressure. Beyond the National Federation of Independent Business survey, which showed a continuing rise in the number of small businesses complaining about rising prices, there was also quite a jolt (pun intended) from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, which showed the number of open and unfilled job positions rising to a record of more than 9 million. This was far more than had been expected. Any sign that this is a job-seekers' market also implies upward pressure on wages, and hence inflation:  There is also no let-up in the rise in commodity prices, another factor that fed concern about inflation. Bloomberg's broad commodity index hit a fresh high for this cycle by the close of Wednesday trading (although, to be clear, it is still some 60% below its peak from the wildly inflated trading in the summer of 2008 ahead of the financial crisis):  This week also brought news from China. As I've written before, another key reason to think that inflation could stage a resurgence is that China now has a strong incentive to export higher prices to the rest of the world, by keeping its currency strong as it ships goods overseas, after decades in which it effectively exported deflation by keeping a lid on wages. Higher commodity prices have a direct impact on the cost of inputs for Chinese producers. And indeed China's producer price inflation has only once in the last 25 years been higher than it is now, and that was during the 2008 commodity spike. On the face of it, this is more reason for rising rather than diminishing concern over inflation:  So why the spasm of doubt? One important factor, identified by Harry Colvin of Longview Economics Ltd. in London, is simple overconfidence. Markets tend to overshoot, and by late March, the betting on yields heading beyond 2% was excessively certain. In such circumstances, the "short bonds" trade became overcrowded. Once there was evidence that the trend wasn't holding, traders asked if they really wanted to be short bonds ahead of an unpredictable inflation report, and bought back. That gave us the results we see in the charts. A second point, Colvin says, is that the bond market tends to react to the most cyclical parts of the economy, and some "mini-cycles" are already showing signs of slowing after a sudden rise. All of these factors are linked. As investors bet on inflation, they leave bonds, cause their yields to rise, and hence raise the cost of mortgages — which will have an effect on the "mini-cycle" of the housing market. In the first three months of this year, the yield on the Fannie Mae benchmark mortgage bond rose from 1.35 to 2.1%, and the growth in housing starts evened off after a sharp increase at the end of last year. But unemployment may be more important than anything else. The course of the 10-year yield over the last two weeks gives a good clue. Yields dipped sharply after the publication of non-farm payroll data at 8:30 a.m. Friday morning (ringed on the chart). They have fallen further since. When the data came out, yields were still solidly in the middle of their range for the last few months. Since then, they have dropped below 1.5%:  What does this tell us? The Fed wants everyone to believe that it is intent on doing an "Inverse Volcker," and persuading us all that it is focused on reducing unemployment, whatever the impact on inflation, just as Volcker convinced the world that he wanted to reduce inflation no matter the impact on employment. The jobs data were, for the second month running, weaker than had been expected. Yes, there are signs of labor shortages and skill mismatches that could imply wage inflation, but the bottom line is that the proportion of the working age population in employment is the lowest since 1983, when the move of women into the paid workforce had not been completed. The Fed wants us to believe that this is what matters most, and if that is true, then rates are going to stay low. Edward Harrison of the Credit Writedowns blog put the thinking of "Bond Front-runners" as follows: - Bond Front-runners are starting to think the Fed's reaction-function may not be as inflation-dependent anymore. Unemployment is front and center. And that's reason to accept lower yields.

- Whether inflation is transitory or not is irrelevant. As long as the Fed is the monopoly supplier of reserves, it can suppress yields to its heart's content. And there's nothing we can do about it.

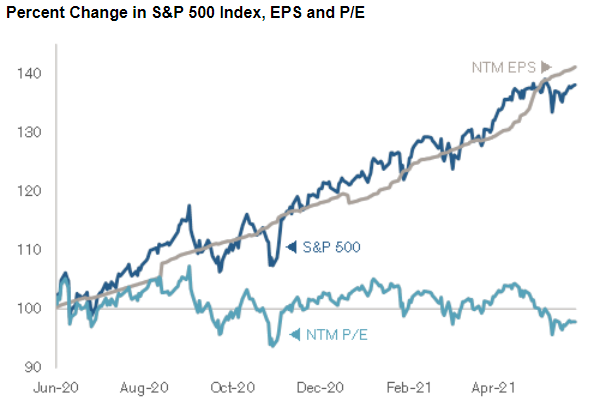

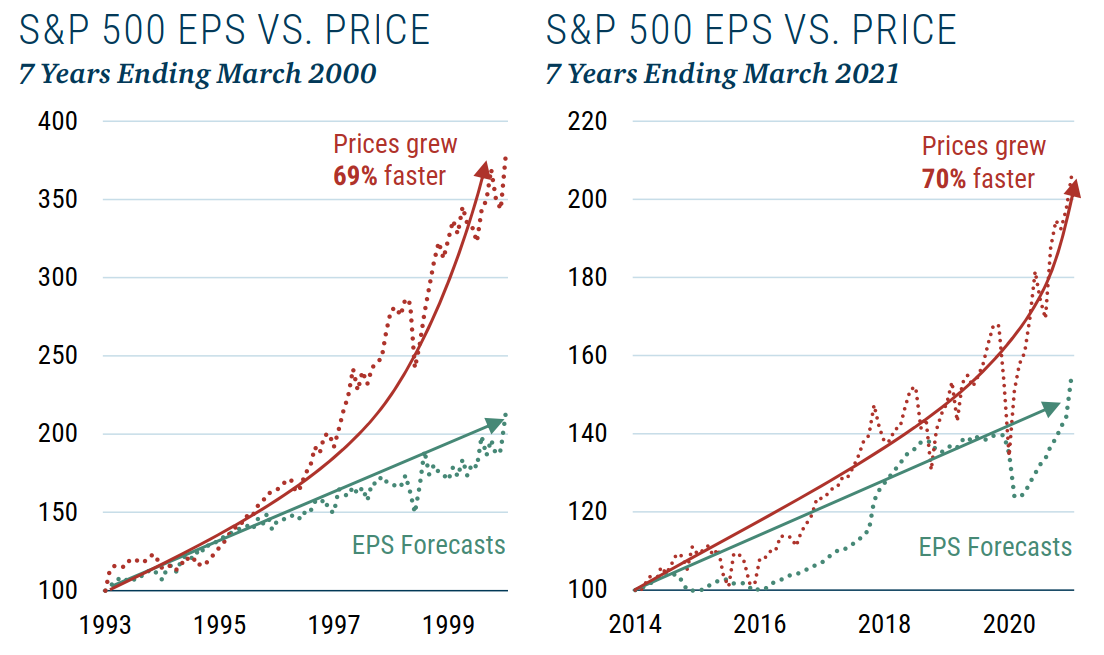

If this is true, then we don't have to worry about short-run inflation numbers, at least as far as bond yields are concerned. Harrison's logic suggests that the employment data matter more to bonds (and they certainly provoked an emphatic reaction to a mixed report last week) than inflation. It is a reasonable hypothesis. And within hours of your reading this, the ECB should have given us a glimpse of the thinking of another major central bank, while the market will have reacted to another U.S. inflation print. So this is one hypothesis that can be tested quickly. An Earned ParallelLast week I published the following chart, from Jonathan Golub of Credit Suisse Group AG. It shows reassuringly that the price of the S&P 500 has moved upward directly in line with growth in earnings estimates over the last 12 months, while the multiple that investors have to pay for those earnings has remained constant. This is exactly how markets are supposed to work, though they seldom do:  Now, let's take a longer perspective. GMO, the Boston-based fund manager, has been under fire for undue bearishness. The rise in earnings forecasts does make it harder to claim that the market is irrationally exuberant or in a bubble, whether or not you believe that is a useful term. But if we look at the longer term, the latest price action appears far less healthy. Over seven years, prices have grown 70% faster than earnings estimates. In the seven years leading to the top of the market in 2000, prices grew faster than profit forecasts by 69%. So the skeptics' argument would be that the rally of the last year only looks sensible because prices have been tracking earnings forecasts that had briefly become artificially depressed:  GMO's paper contends that there are no bad assets, just bad prices. Its rather deflating take is as follows: - Even great companies with great narratives can still experience price movements that are too great.

- This would not be the first time. The left chart above compares EPS forecasts with the S&P 500 price index in the 7-year period leading up to March 2000. Back then, the excitement of new technologies combined with growing confidence in the Fed had expectations running high. Wall Street EPS forecasts were rising healthily. Prices, unfortunately, moved even faster – 69% faster. This, as you know, did not end well.

- Today history is rhyming. The new business model narratives are compelling – high growth, asset-light, network effects, high switching costs, etc. Wall Street EPS forecasts are rising healthily. The problem is that prices are again growing 70% faster. This, as you suspect, cannot end well.

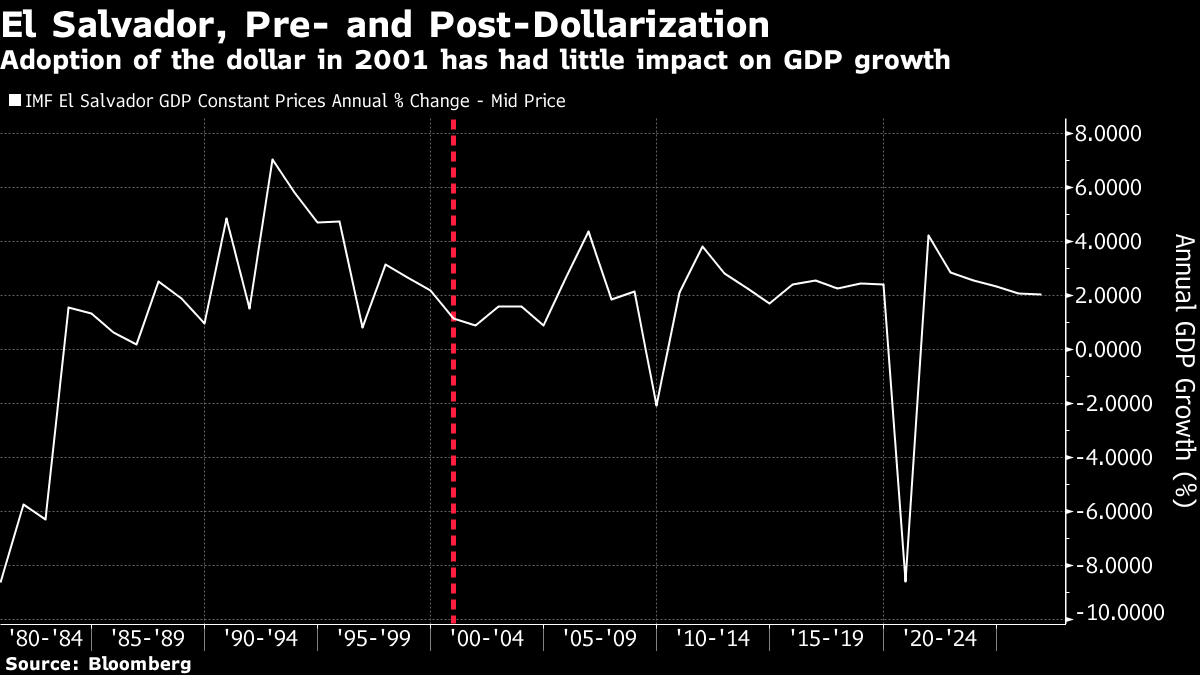

Maybe we shouldn't call this a bubble. But the exuberance appears to be contagious once more, and once again there appears to be a belief in a new economic paradigm, as there was in the late 1990s. Although at least this time the Fed isn't calling it anything like that. El Salvador's New SaviorEl Salvador has become the first country in the world to accept bitcoin as legal tender, following a decisive vote in Congress. It is a big moment for the Central American nation and its young president, Nayib Bukele, and it is also a big moment for cryptocurrency. But it is not quite as big a deal as it appears. Arguably the single biggest reason for doubting some of the more optimistic claims made for cryptocurrencies is that governments currently enjoy a monopoly on providing money, and will be loath to surrender it. Should bitcoin or any rival get too strong, the argument goes, governmental authorities will squelch it. Without the freedom to issue currency and set monetary policy, governments' freedom of action (and hence, arguably, the freedom of action of those who voted for them) is drastically curtailed. These arguments don't apply to El Salvador. It did away with its own currency, the colon, in 2001, and replaced it with the U.S. dollar. In Latin America, Panama and Ecuador have also "dollarized." This is a painful loss of sovereignty, but in the case of El Salvador, about the size of Wales with a population of 6.4 million and a GDP of about $27 billion, it appeared to be a justified move. The country is hugely dependent on the U.S., where many Salvadorans work, and at the time it was still recovering from a long and bitter civil war. Sacrificing control over monetary policy allowed it to import stability from the U.S. It also made it easier and cheaper for migrant workers to send money home. In the event, dollarization doesn't seem to have had quite the effects hoped. GDP growth since dollarization has been a bit slower than in the preceding decade, and the IMF projects that to continue:  Accepting bitcoin should continue to make life easier for migrant workers sending money home. It might have many more positive effects, and so this experiment should be watched closely. But the key point is that El Salvador had already made the decision to surrender its monopoly over issuing currency two decades ago. If a country that still prints its own banknotes were to follow suit, that would be far more significant. Survival TipsMoving on from El Salvador, I will stick with the salvation theme. Apple Music decided this week that I would like to listen to Sole Salvation by The Beat (known as The English Beat in the U.S.) And, it's sinister but true, Apple is right. I'd completely forgotten what a great song it was, with an amazingly infectious (and swift) bass line. It's up there with my other favorite Beat song, Mirror in the Bathroom. The only other bass line that I can think of that's anything like it is Town Called Malice by The Jam, from the same era. All the other famous big bass riffs I can think of are much slower — Another One Bites The Dust by Queen, or Good Times by Chic, or Billie Jean by Michael Jackson, or I Threw A Brick Through A Window by U2. They're all fun. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment