April Really Was the Cruellest MonthApril is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

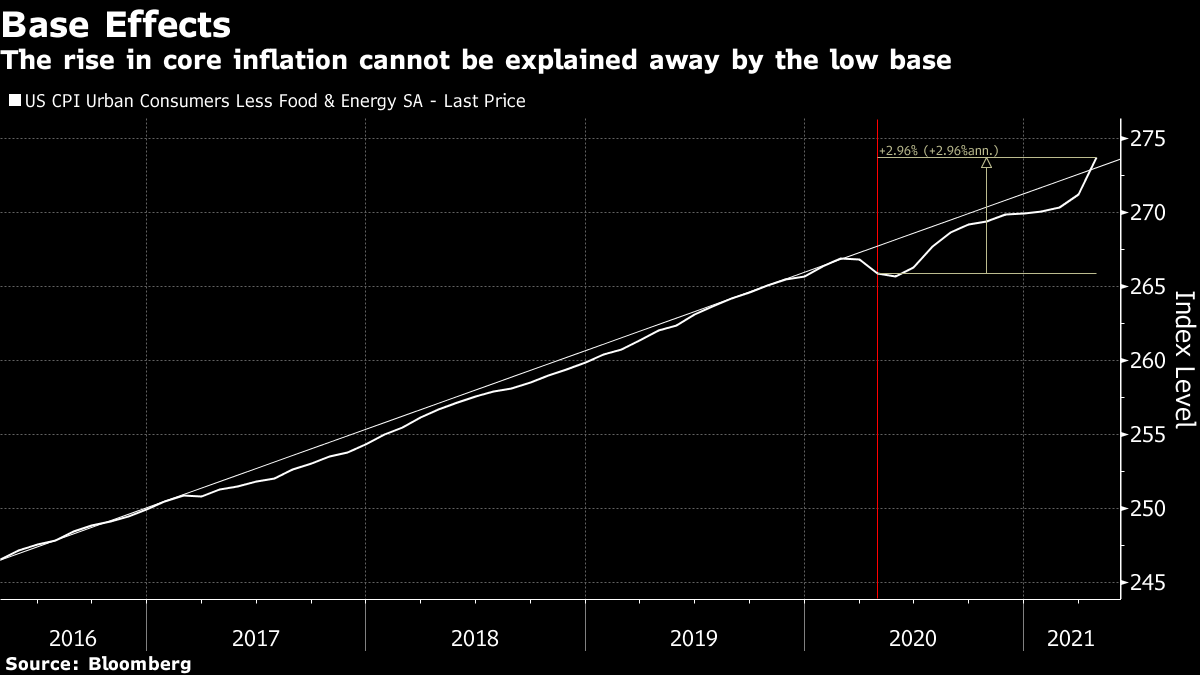

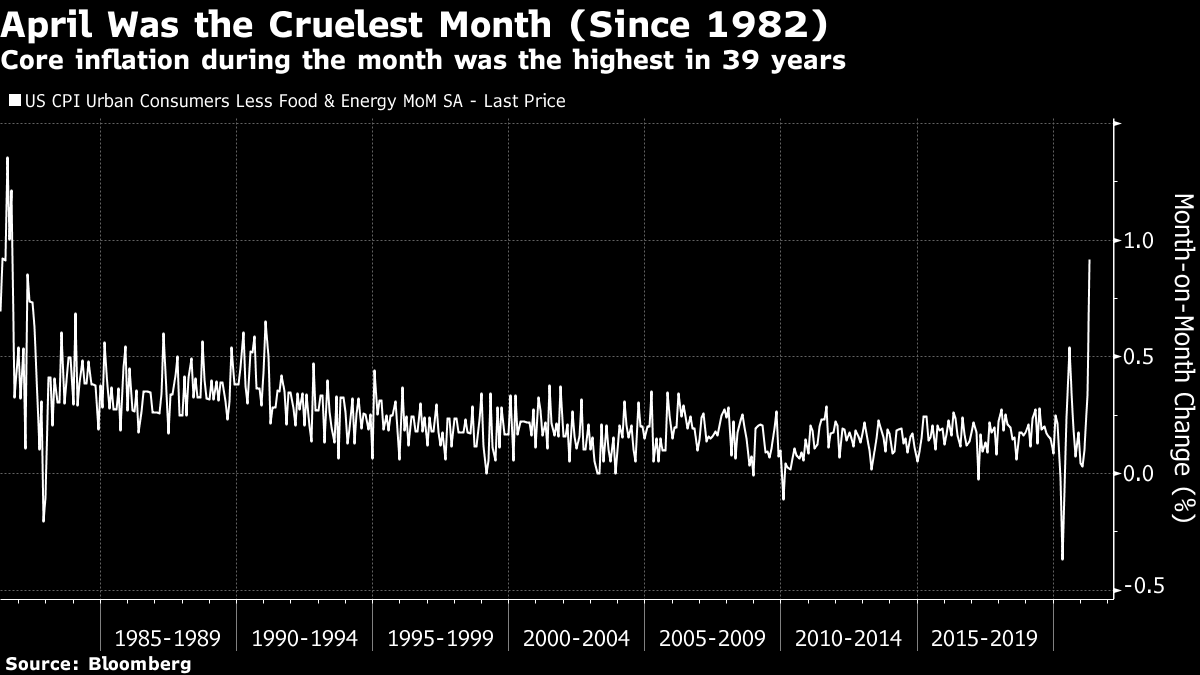

The opening words of the most famous poem written in English during the 20th century, T.S. Eliot's The Wasteland, have long since suffered an unfair fate as a journalistic cliche. If anything bad happens in April, we can say it was the cruelest month. In fact, we can and do say that when anything bad happens in any month. Much the same fate has been visited on the opening words of Shakespeare's Richard III. If something bad happens during the coldest months of the year, we can generally label it a "winter of discontent." So, to be clear, this April really was cruel. In terms of the basic economic numbers that affect us most, it was the cruelest month for the U.S. in many decades. It was only one month. It is way too soon to proclaim the beginning or end of a major economic trend, on the base of the data we have so far. But April's data were not only very, very bad, but also very, very surprising. They need to be confronted and understood. The most important thing to understand that this is not all about that base. If we look at the core consumer price index, stripping out the impact of oil's collapse 12 months ago, we can see a clear trend. For a few months, price levels dipped sharply below it; and they have now resurfaced above the pre-existing trend. It was always known that the low base set last spring would create high year-on-year numbers; but these go beyond what can be explained by that base effect:  To illustrate the same thing a different way, the following chart shows month-on-month changes in core CPI going back four decades. For these numbers, what happened 12 months ago is irrelevant — and April proves to have had the highest inflation in four decades:  Yes, this is is only one month's data. The fact that they are surprising means we should look at them carefully. There are no good precedents for a shock of the magnitude of the Covid pandemic, so it is possible there are many unexpected and nasty but also transitory economic effects in the pipeline. That said, April also saw a shocking surprise in the unemployment data. When both the key economic variables register a major and profoundly negative surprise in the same month, it behooves us to pay attention. The DataWhat are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish?

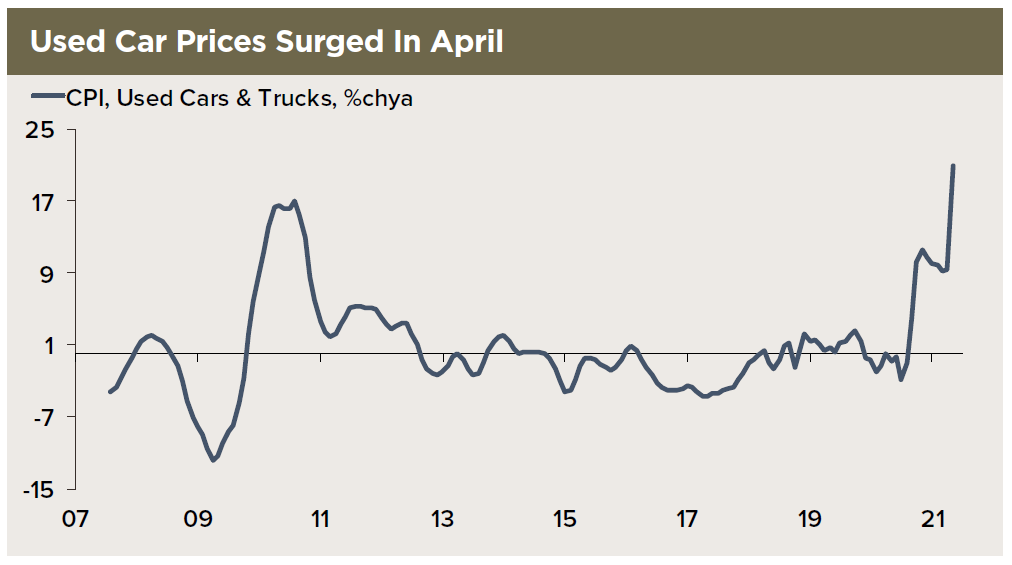

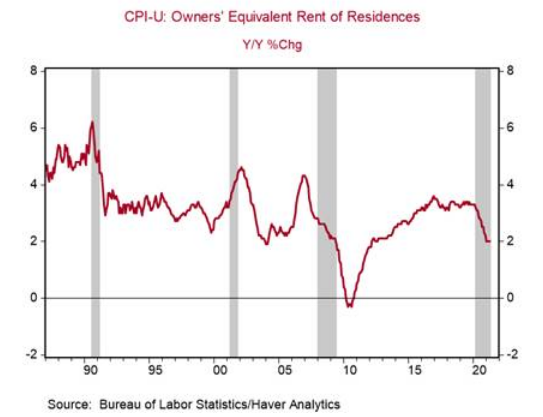

There are a number of bizarre numbers within the data that plainly wouldn't have happened without the pandemic, and must be transitory to an extent. Most notably, inflation in the prices of used cars and trucks took off as rental companies struggled to cope with reawakened demand:  But there are also elements that suggest inflation could yet grow significantly worse. Most important is shelter inflation, measured by the effective rent that owners pay for their homes. This declined to 2% despite a sharp pick-up in selling prices. It is hard to imagine that it will stay this low. The prices of services excluding shelter rose 1% for the month, and 3.2% year-on-year. At this point it is the services sector that can expect the greatest impact from increased demand as reopening continues. So while elements in the numbers are plainly blips, there are also large sectors of the economy where it is reasonable to fear that the greatest inflation lies ahead:  Mickey Levy of Berenberg Capital Markets LLC puts the issue for the future succinctly: The issue of whether the rise in inflation is temporary or more persistent depends critically on the trajectory of aggregate demand. If it remains strong after the economy reopens, as we project, based on the unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus, inflation pressures will mount as costs of production will continue to rise and businesses will have flexibility to raise product prices. The Fed's ability to manage inflationary expectations will be tested.

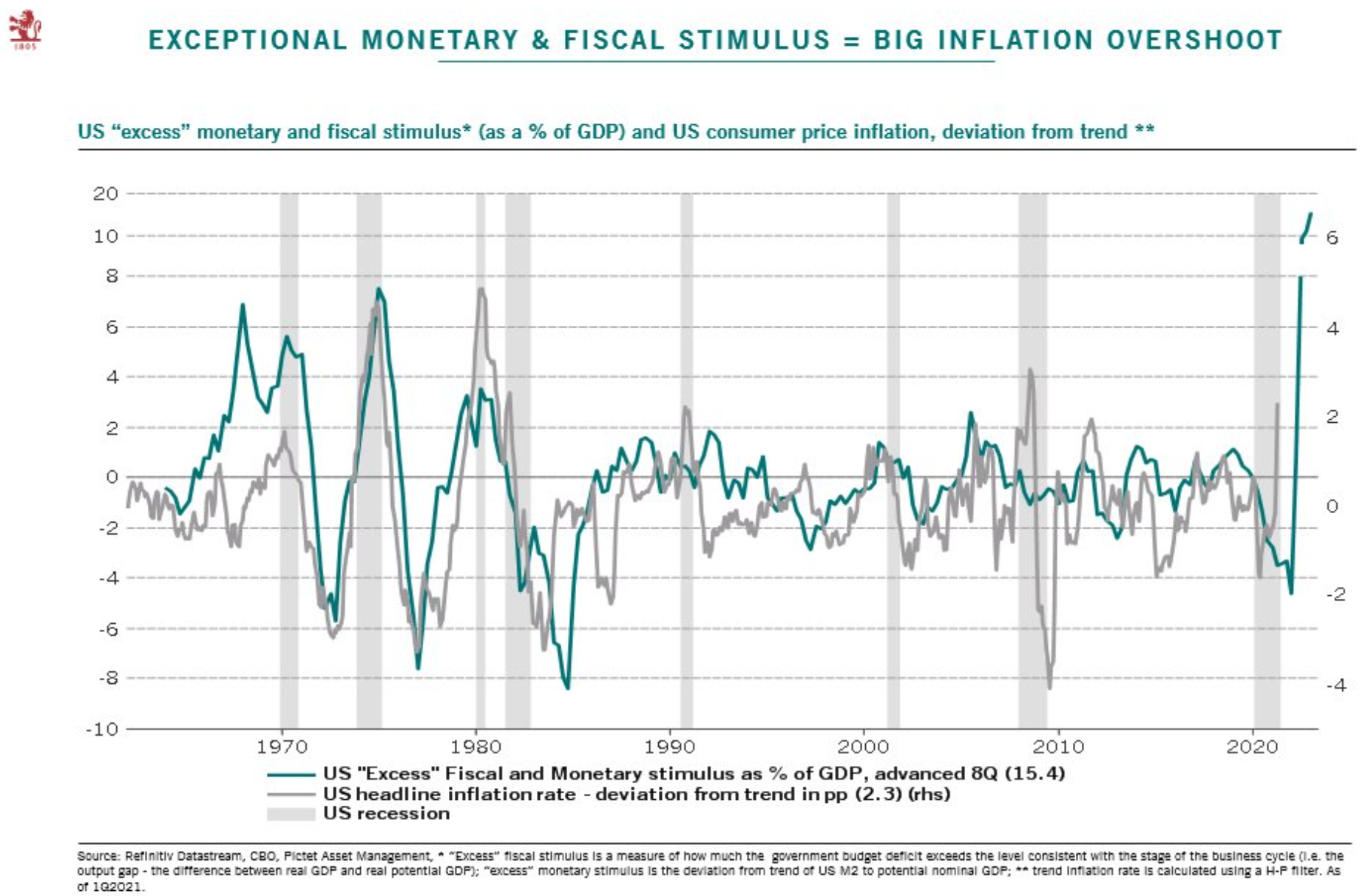

The scale of the excess monetary and fiscal stimulus already in the system makes it eminently reasonable to assume that plenty of extra aggregate demand lies in our future. This chart, from Luca Paolini of Pictet Asset Management, shows the relationship neatly. After this big a stimulus, it is reasonable to expect inflation to respond over the next year or so:  The Dominos"My nerves are bad tonight. Yes, bad. Stay with me. "Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak. "What are you thinking of? What thinking? What? "I never know what you are thinking. Think."

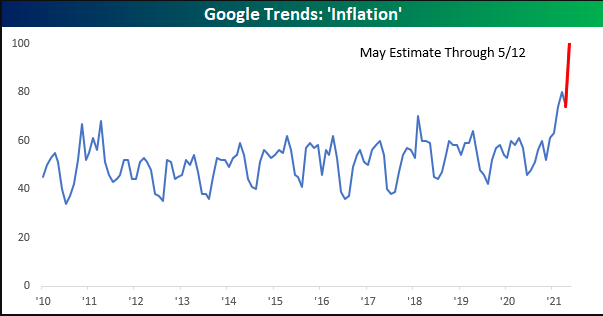

Inflation psychology depends on expectations. If people expect inflation to rise in the future, they are more likely to buy products in a hurry before prices rise, and will become far more assertive in their wage demands. By so doing, they will raise prices themselves and increase inflation. Until now, the inflation scare has been restricted to financial professionals drawing reasonable inferences from unprecedentedly easy monetary policy and the disruptions caused by the pandemic. That inflationary angst had, crucially, not been shared by the public at large. This appears now to be changing. The following chart, from Bespoke Investment Group, tracks Google searches for the word inflation, going back to 2010. Judging by search activity so far this month, public concern has just hit a far higher level than seen before in the post-crisis era:  A bad unemployment number followed quickly by a bad inflation number also has an effect on the political reality, which could in time counterbalance growing concerns about inflation in the population. So far this year, the story has been of the unexpected political ascendancy of President Joe Biden, who used his first 100 days to great effect. Helped by success with the vaccination rollout and by initially good economic numbers, he pushed through another dose of stimulus with surprising ease, and soon shifted the agenda on to an infrastructure plan, with extra taxes to pay for it. That political honeymoon now appears to be over, and more numbers like this could soon drive the new administration into trouble. That changes some of the market's more optimistic assumptions about growth. But it also changes the assumption that both fiscal and monetary policy will push hard in an inflationary direction. If it already looks as though inflation has been uncorked, it grows much harder for the administration to launch more spending projects — and that reduces the risk of surging prices ahead. The Markets The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers, Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed. And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors; Departed, have left no addresses.

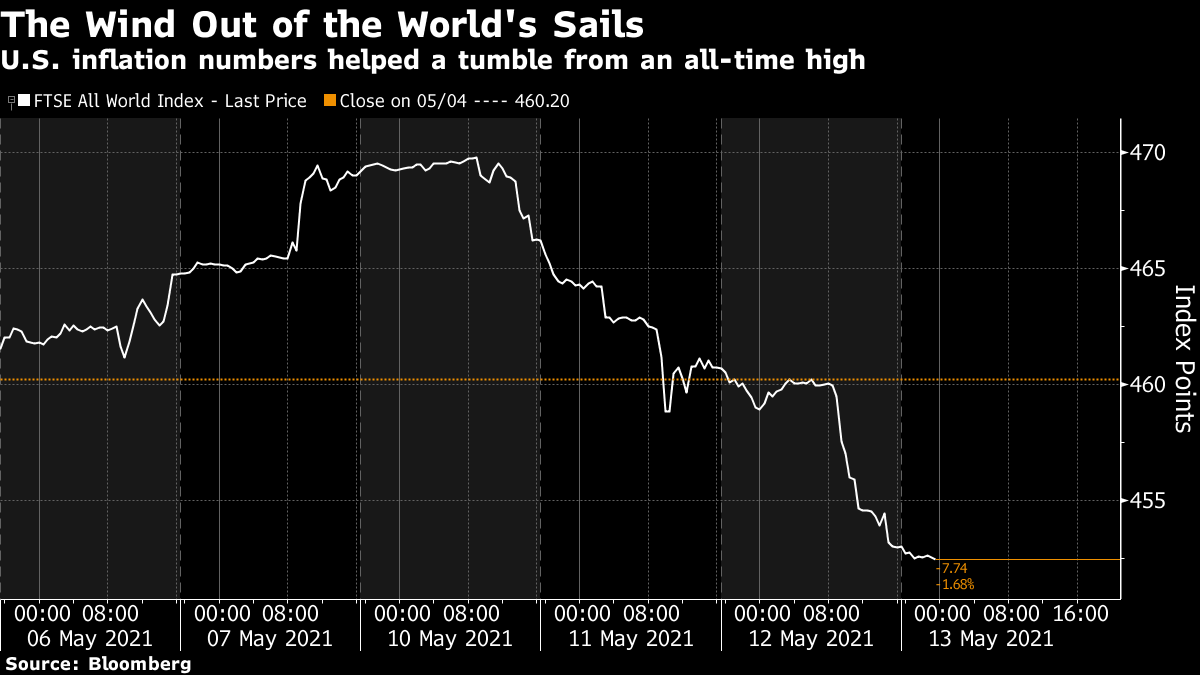

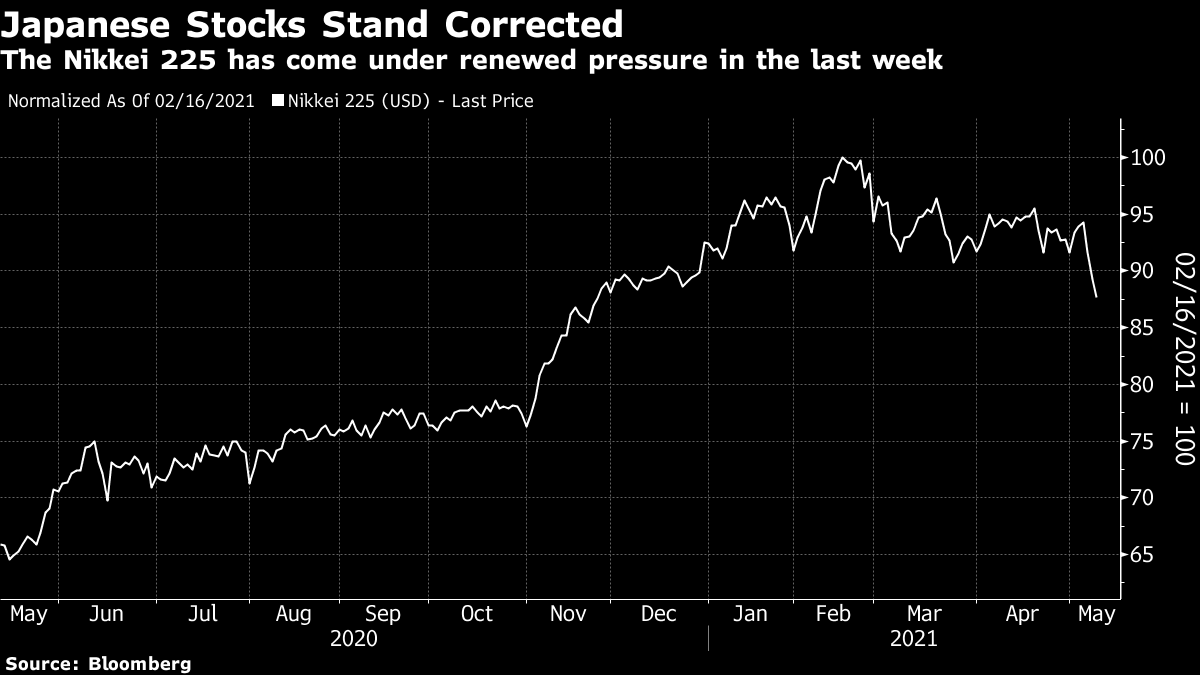

This drastic surprise created a surprisingly muted reaction in the markets most directly affected. Bond yields rose across the board, though stayed within their post-Covid ranges. The yield curve also steepened without breaking above its previous high for the cycle. This number has definitely sent sentiment back in an inflationary direction, but it's not making new territory. Inflation breakevens did continue to rise, which isn't at all surprising. Again, it is possible to overstate this. Perhaps most intriguing is the 5-year, 5-year breakeven that measures expected average inflation over 2026 to 2031. This has long been the Federal Reserve's single favorite measure of market expectations, and it rose sharply to stand at the highest since 2014. But unlike the 5-year breakeven, which reflects expectations for the next five years, it remains significantly lower than it was earlier in the post-crisis decade. Still below 2.5%, this measure suggests the market doesn't believe inflation is going to get out of control. To use the word of the moment, it suggests inflation is still thought to be transitory:  It is worth emphasizing how unusual this is. The next chart shows the spread between the 5-year breakeven and the 5-year, 5-year measure going back to 2006. Almost all of that time, markets positioned themselves for inflation to be higher over the subsequent five years than over the immediate period. The current position, with inflation seen lower in 2026-31, is very unusual, and suggests that in the sense that probably matters most to the Fed, the market still expects it to be a transitory phenomenon:  In the weeks and months ahead, the level of breakevens will be vital to monitor. But the spread could be crucial. If the 5-year, 5-year overtakes the 5-year once more, and the spread returns to the kind of levels seen earlier in the post-crisis decade, that would be a bad sign for the Fed, and would probably put a lot of pressure on the central bank to change course. Elsewhere in markets, the most dramatic reaction was in stocks, where the response was impressively uniform. Cutting and dicing the figures many different ways on the terminal, I find it hard to see any great rotation or shift. Rather, this was a broad markdown. Sectoral, factoral and geographic effects were surprisingly limited. And as world stocks set an all-time high as recently as last week, it is hard to get too alarmed or scared just yet. The fact that stock markets are so high, of course, does leave ample room to worry that there's a long way down. This is how FTSE's all-world index has moved over the last week, gaining on the dreadful U.S. unemployment data, slipping Monday, and dropping much further Wednesday after the inflation number, in a reaction that continues in Asian trading at the time of writing.  One disquieting development is the impact on the Nikkei 225. Nobody expects inflation in Japan, but its presence in the U.S. makes Japanese assets that much less attractive, as they are unlikely to provide much of an inflation hedge. In dollar terms, Japan's best-known index has corrected, and is now down more than 12% from its February peak:  This isn't that great a reaction to numbers that could still prove transitory. But the reaction in stocks does demonstrate that they have been priced for perfection. If inflation does take root, they have plenty of room to fall further. Survival TipsMaybe try reading The Wasteland, which you can find here. I haven't sat down to read it since I was at high school. It's a lot harder to understand than even the inflation numbers, but there is a lot in there. The language stays rich and arresting long after the famous first lines. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment