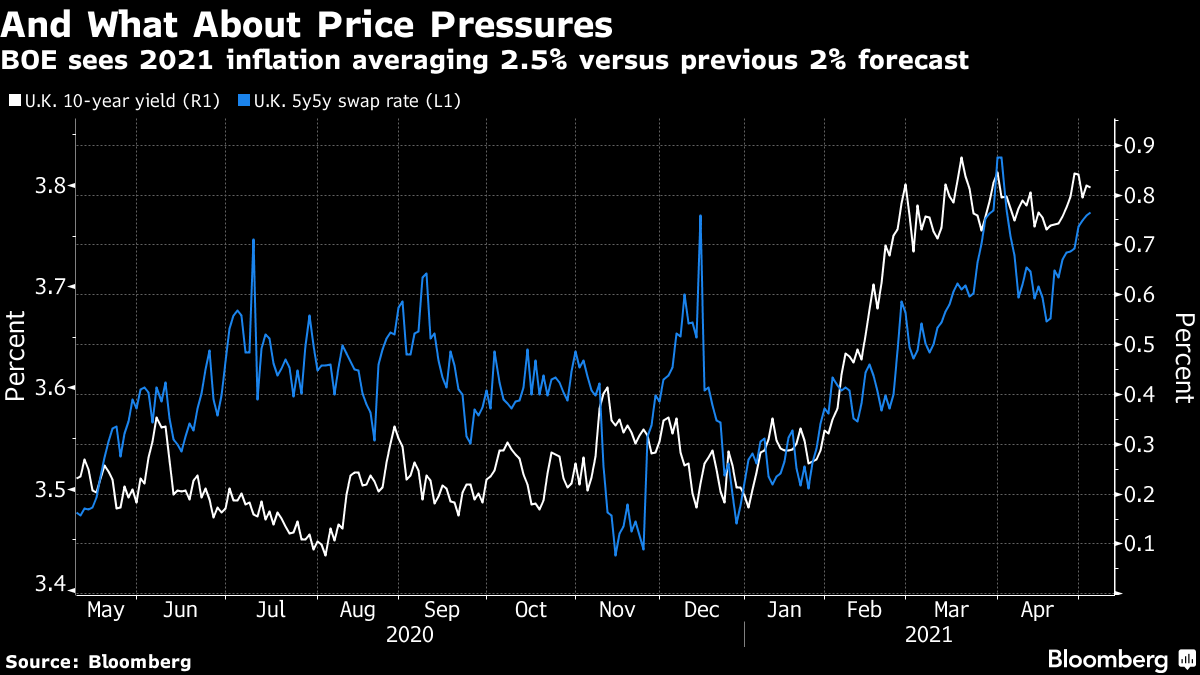

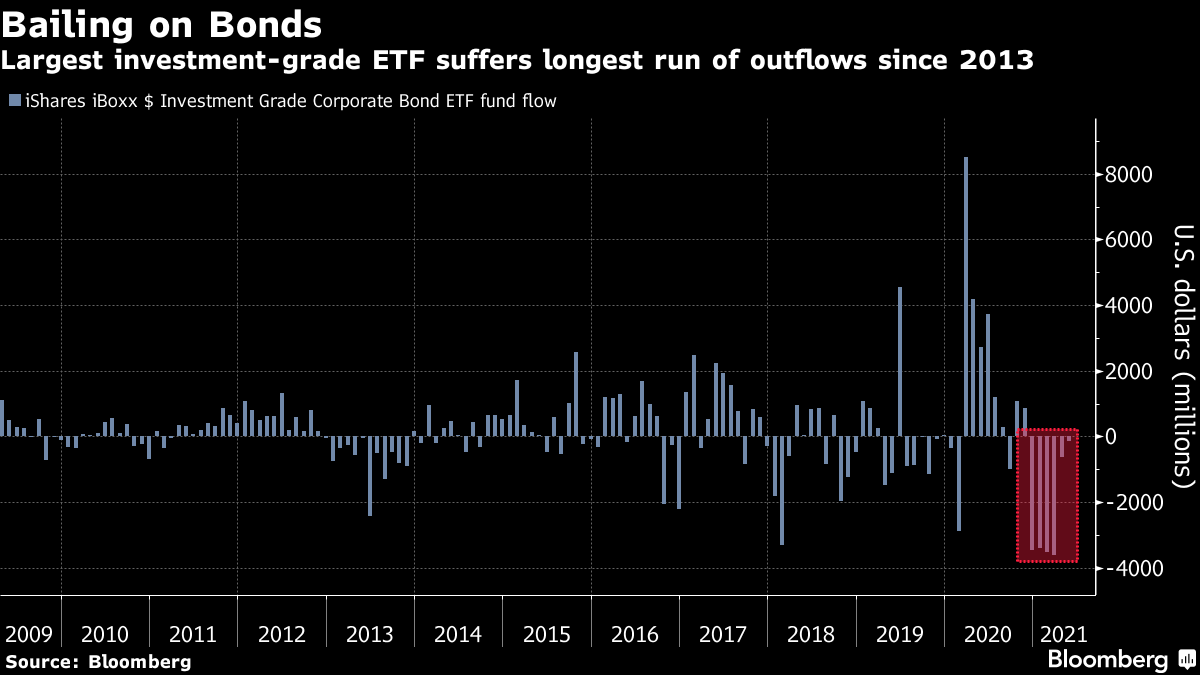

| Welcome to The Weekly Fix, the newsletter that sees the canard in all this taper-tantrum talk. --Emily Barrett, Asia cross asset editor/reporter A taste of taper...Bank of England: "This operational decision should not be interpreted as a change in the stance of monetary policy." Right-o. The Old Lady of Threadneedle St, as the Bank of England is affectionately known, sounds a little like she's thinking of cutting the apron strings. That is, policy makers announced they won't be buying quite as many bonds each week. About a billion pounds fewer, in fact. In case that alarmed anyone, they also said that the size of the program's current installment is unchanged, at 150 billion pounds ($209 billion). And the statement above asserted categorically that this is not a taper. We're prepared to put this to the duck test. And it couldn't be more like a duck if it quacked, swam in a pond, or was stuffed with a bayleaf and celery stick by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall. (Note: avoid the pineapple recipe, it looks awful) The BOE's smaller weekly purchases (3.4 billion pounds) do mean that the program could extend for longer, to around year end, instead of just to the start of November. But it's also possible that if all goes swimmingly (sorry -- nearly done with this metaphor), the Lady could take another snip in August. This latest hint of a pullback in emergency policy settings among the major developed-market central banks is interesting for what it's not doing. As was the case when the Bank of Canada announced a more explicit taper last month, there's no freakout. Of course, global markets may just be holding their breath while the U.S. keeps ducking the question. Eight years ago this month, global yields jumped and risky assets fell on a hint from then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke that the central bank might start trimming its crisis-era bond program. Bonds took the brunt of that turmoil, with Treasury yields jumping 50 basis points in the month after Bernanke spoke. Over the same period the MSCI Emerging Markets Index slumped 14% and the Nasdaq 100 fell 4%. This week, though, gilts actually outperformed Bunds and Treasuries on the assurance that the BOE won't raise interest rates until there's clear evidence of an economic rebound. Money markets kept pricing for hikes steady, with an 11 basis point increase in August 2022. It's testimony to how well the dovish message went down, that traders looked through the BOE's growth upgrade -- which our reporter Lucy Meakin described as "whopping" -- to 7.3% this year from 5.1%. It helps that U.K. inflation is mired at pretty low levels, around 0.7% on the year by the latest count, though expectations have risen significantly.  And the relatively breezy reception for the BOE is heartening for other central banks contemplating an adjustment in their crisis-mode policy settings. Australia decides in July whether it will shift the target under its yield curve control policy to a more-recently issued bond -- if not, that could be a hawkish signal for markets. Deputy governor Guy Debelle this week included a little twist on the Reserve Bank's common refrain that the conditions for higher interest rates are unlikely to be met until 2024 at the earliest: "It is the state of the economy that is the key determinant of policy settings, not the calendar." It will obviously help if central bankers can coordinate their message. The European Central Bank may even have dropped some hints Friday, with Governing Council member Martins Kazaks saying a decision to slow purchases could come as soon as next month. And Norway this week made no bones about its plans to lift its policy rate off zero later this year, becoming the first developed-world central bank to embark on a cycle of rate hikes since the pandemic struck. This concerted, if gradual, shift toward a massive global policy unwind is the stuff of dreams for macro-driven investors, says Pilar Gomez-Bravo, a London-based director of fixed income at MFS International. "What's so exciting in multi-asset investing is that we know there's going to be dislocations, because not all central banks are going to manage the exit well. So you're going to have volatility coming back in, and not all asset classes are priced to see periods of volatility," she said. The 86-billion-pound duck in the roomThe Federal Reserve isn't thinking about tapering still, but some policy makers are gesticulating. The case they're building is centered on the risks to financial stability. "We're now at a point where I'm observing excesses and imbalances in financial markets," Dallas Federal Reserve Bank President Robert Kaplan said on April 30. "I'm very attentive to that, and that's why I do think at the earliest opportunity I think it will be appropriate for us to start talking about adjusting those purchases." Kaplan was the first in what's looking like a chorus. Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren told Bloomberg TV this week that maybe the thriving U.S. mortgage market didn't need much more help. Of the Fed's $120 billion monthly purchases, it's targeting roughly $40 billion in mortgage bonds, so perhaps it's fair to guess that if the central bank is looking to trim, it might start there. And the central bank's latest semi-annual Financial Stability Report seemed a little bolder than usual. The Fed put in stilted terms what market watchers who may not exactly be the life of the party on Reddit have been worrying about for a while. Meme stocks and SPAC IPOs earned multiple mentions as evidence of "a higher-than-typical appetite for risk among equity investors." "The combination of stretched valuations with very high levels of corporate indebtedness bear watching because of the potential to amplify the effects of a re-pricing event," Fed Governor Lael Brainard said in a statement alongside the report. And all this comes after we heard Fed Chair Jerome Powell allude to "frothy" parts of the market in his April press conference. Markets seem to be taking their excesses and these expressions of concern in stride so far, with volatility low and financial conditions still around the loosest ever. But traders appear to be quietly setting their sights on apossible taper announcement at the Fed's picturesque annual meeting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. That's judging by a large options position that our rates mavens Stephen Spratt and Edd Bolingbroke have been eyeing in the Eurodollar market. The punt is on a faster-than-expected pace of hikes before September 2024, and it expires after the Fed's get-together. Duration bets on-again, off-againAt the other end of the market from the Wyoming Whale, we have other signs of taper awareness (and no sign of tantrum). That's the cooling enthusiasm for duration. Investors have been shying away from bonds that are most vulnerable to losses from rising interest rates -- that is, longer-dated and higher-quality debt where yields are already anemic. Duration risk on the benchmark Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Index is close to all-time highs:  This index series shows the worst losses on record for U.S. government bonds at the far end of the curve on record last quarter, at close to 14%. Investors in high-duration bonds have been voting pretty loudly with their feet, as the largest investment-grade exchange-traded fund is on its sixth month of outflows -- the longest string since the taper tantrum year of 2013.  The worst may be over for now, as that exodus has at least slowed. The long end of the curve has steadied in recent weeks as the market appears to have priced in the more-optimistic expectations for growth that sprung up around President Biden's stimulus proposals. And the ensuing buzz over inflation risks has settled. That has emboldened contrarians such as Northern Trust Asset Management to load up on duration, on the view that the U.S. 10-year benchmark is stuck in a range well below 2% for the rest of this year. But the broad trend away from duration risk is still clearly in place. MFS's Gomez-Bravo is among those favoring junk bonds for their lower interest-rate sensitivity. Moreover, she expects they may fare better in a taper if we are indeed the early stages of the credit cycle -- such as you'd typically see in a recovery, when growth is on a sustainable upswing, and defaults are less likely. That said, she warns that the asset class has changed in recent years. And that's not just because high yield is no longer high yielding. "Interestingly, there is a fear of duration in high yield," Gomez-Bravo said, as the last crisis saw ratings down grades plunge more investment-grade issuers -- who tend to have longer-maturity debt -- into the junk bond market. In addition to those fallen angels, the riskier credits have in some cases been able to take advantage of record low interest rates to extend the maturities of their borrowing. Bonus PointsWomen get top jobs at funds, just not the ones that manage money Judging by its social media profile, this $250K squid statue may already be earning its keep The undoing of a knitting community. And ahead of Elon Musk's SNL stint: Mars may actually be doable... so should we start taking UFOs seriously? |

Post a Comment