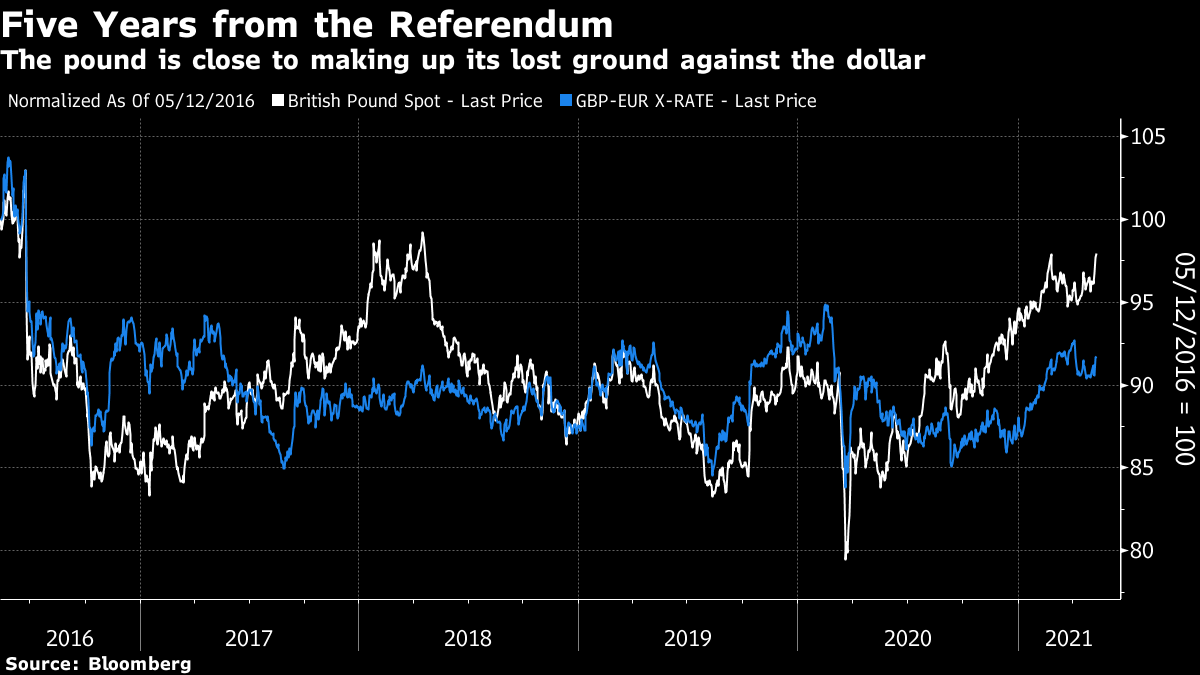

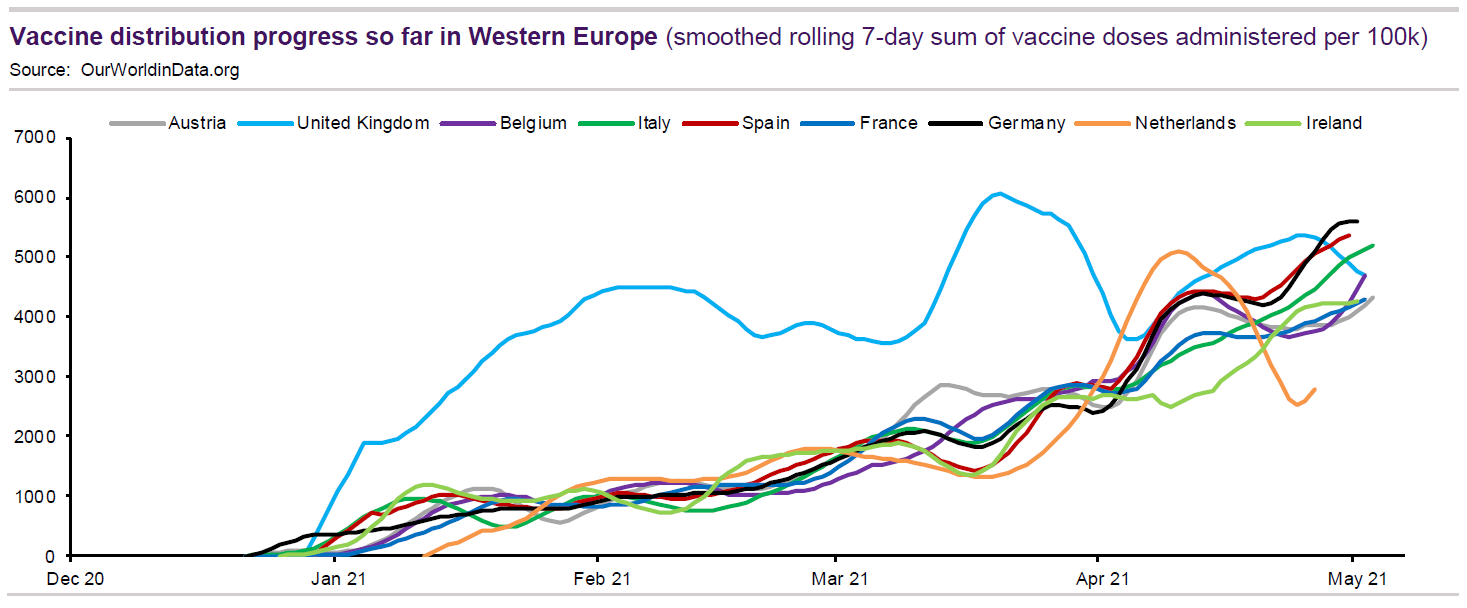

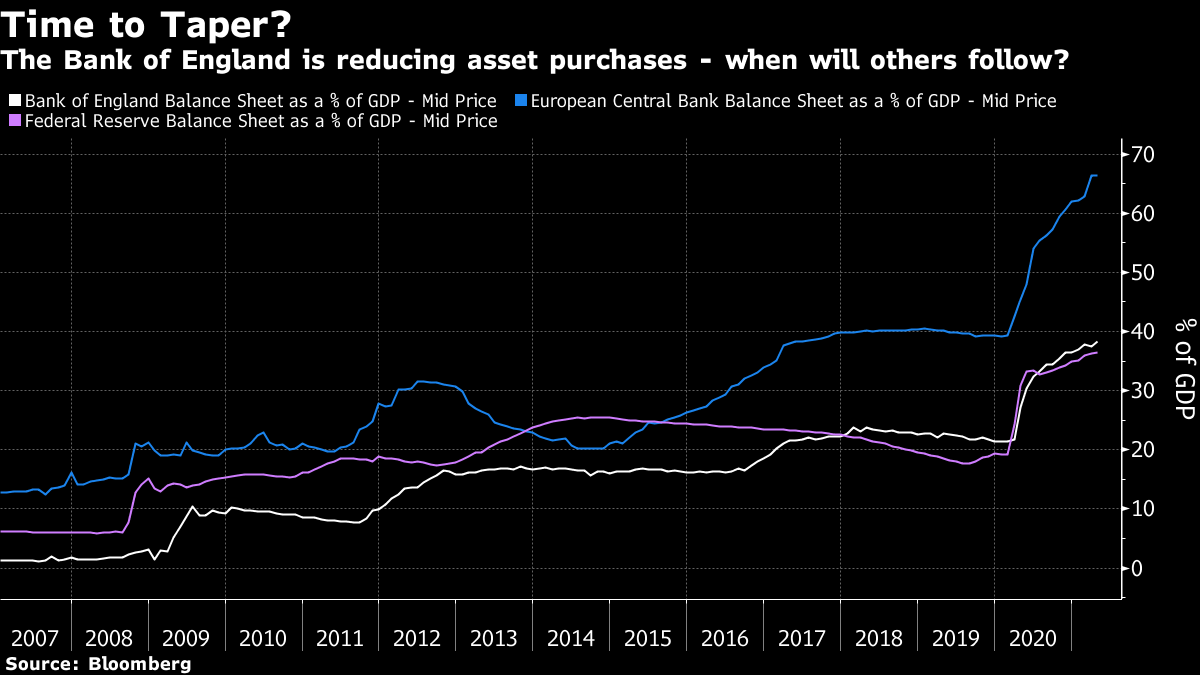

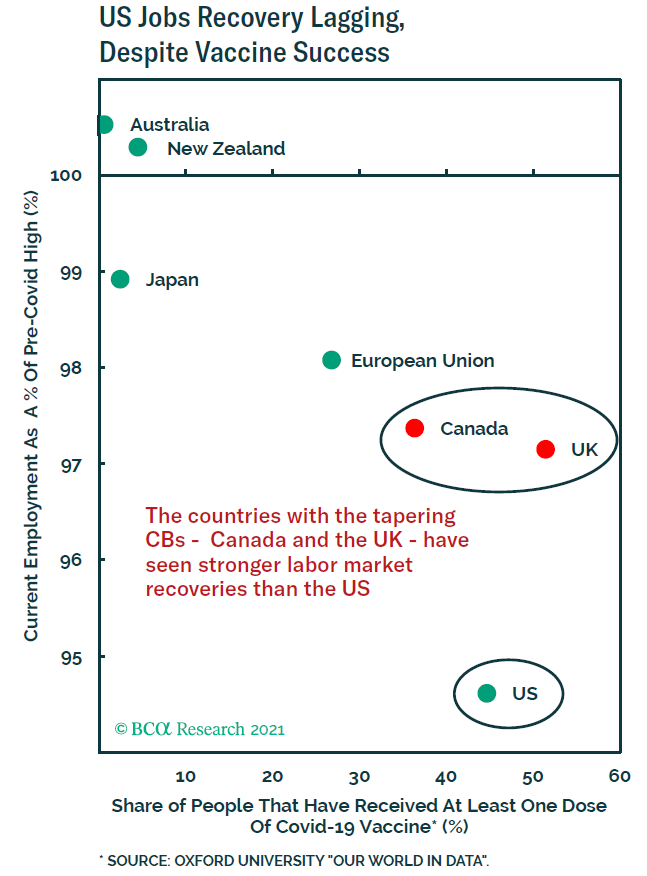

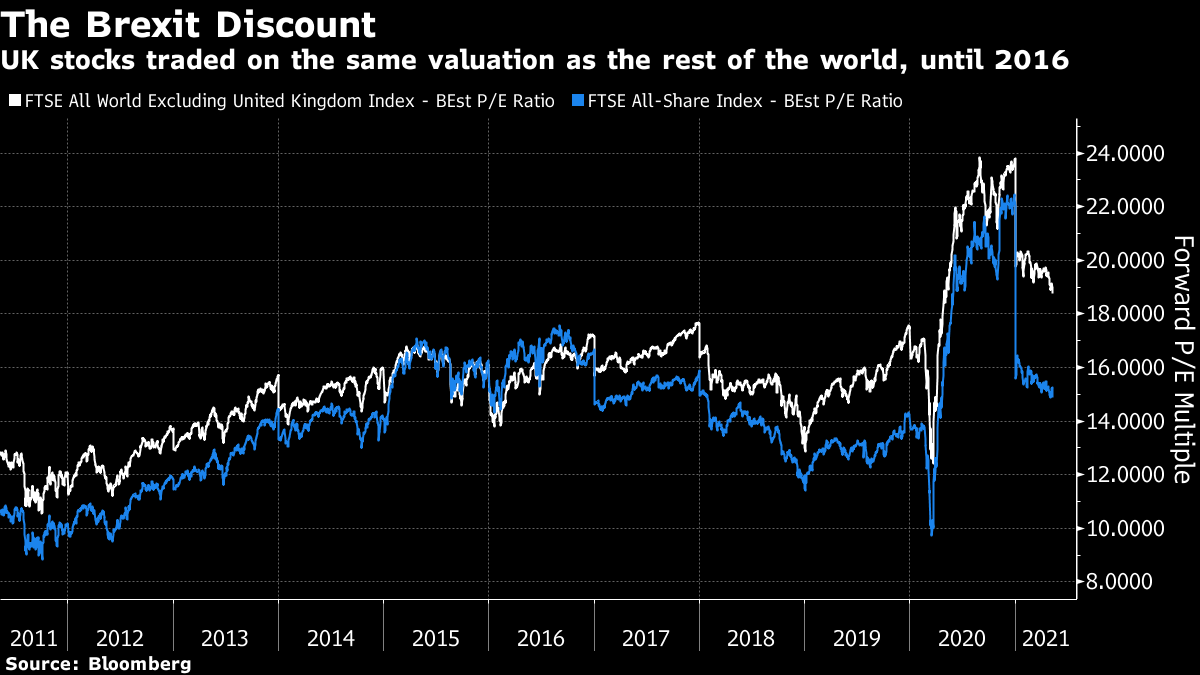

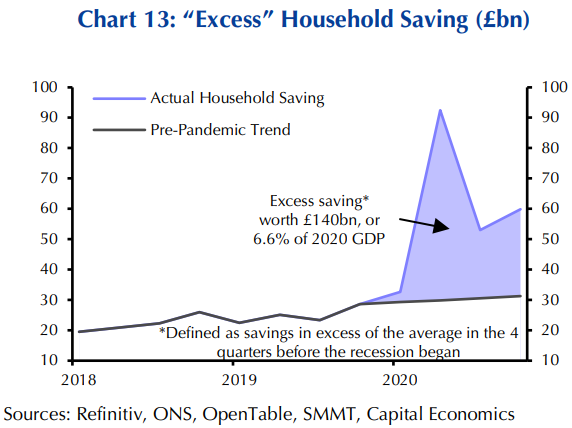

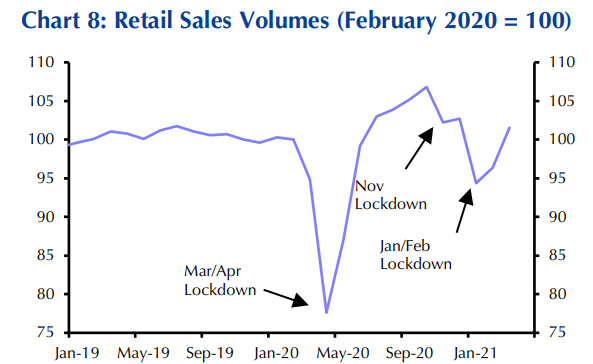

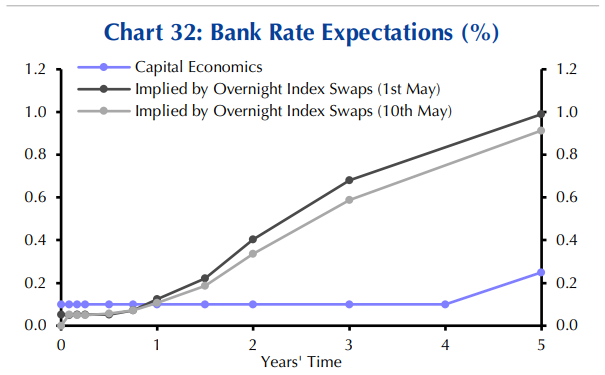

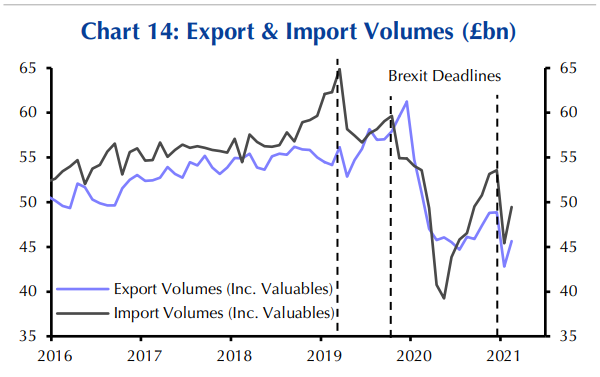

Happy AnniversaryNext month brings the fifth anniversary of the U.K.'s decision to leave the European Union. I didn't vote for it, and still wish that the country had chosen a different direction. But at this point, after an initial hit that was worse than Brexit's proponents had forecast, followed by four years of political chaos that shook the country to its foundations, the damage is looking rather more limited than opponents like me had expected. The U.K. continues to show signs that it could be an interesting investment opportunity. It is also set up to be a fascinating testing ground for post-Covid economic effects as countries emerge from the pandemic. Referendum night, in June 2016, saw the biggest one-time fall any major currency has suffered in a free-floating exchange rate regime. For most of the post-Brexit period — with an exception in the latter half of 2017 as the dollar weakened during President Donald Trump's first year — the foreign exchange markets have been comfortable with that big devaluation. The pound has rarely risen above the point where it came to rest on the day of the referendum result. But that is now beginning to change. Against the dollar, the pound is its strongest since early 2018, while it is approaching the top of its post-Brexit range against the euro:  Most of us know the main reason for the rebound in sentiment. The U.K. handled the Covid vaccine rollout better than any other leading economy. Other European countries are now beginning to catch up, but the U.K. should be some months ahead in its emergence from the pandemic, as this chart from Natwest Markets shows:  That helps to support the currency. More tangibly, the Bank of England announced last week that it was starting to taper the asset purchases begun last year to help the economy through the pandemic. It is doing so ahead of the Federal Reserve, which is still not talking about talking about tapering, and the European Central Bank, whose asset-buying program is currently much more aggressive:  The BOE can withdraw stimulus earlier than the Fed because U.K. employment has made up far more of its losses since the start of the pandemic than the U.S. has. The same is true of Canada, whose central bank is also now in the tapering club, as this chart from BCA Research Inc. shows:  Arguably, the employment outcomes for the EU and the U.K. support their policy of paying companies to keep workers in jobs, as opposed to the American approach of offering generous benefits to those laid off. Maintaining the link between worker and company appears to have made it much easier to bring employment levels back up again in the last few months. Another argument for the U.K. comes from its relative political stability. In the U.S., President Biden depends on a knife-edge majority in the Senate, and reapportionment of House seats means that he is very likely to be in a deadlocked situation, with at least one house of Congress controlled by the opposition, by the end of next year. The continued refusal of a large section of the Republican Party to accept the result of last year's election continues to look very bad from outside the country. Meanwhile, Germany has a wide-open general election later this year, which will result in a chancellor not called Merkel, and might quite easily put the Greens into a position of power. France has a presidential election next year. In the U.K., by contrast, the market-friendly Conservative government has a comfortable majority in parliament that gives it wide freedom of movement. It doesn't have to hold another election until 2024. If it opts for an earlier one, it will be because the government is confident. Last week's local and regional elections saw some terrible losses for the main opposition Labour party, which won't worry the markets at all, and have been followed by a ghastly farce in which the leader tried to demote his deputy (who is directly elected by party members), and was forced by the resulting outcry to give her more power by the end of the weekend. Meanwhile, the Scottish Nationalist Party narrowly failed to gain an overall majority of seats in Scotland's parliament, making it much harder to call a potentially destabilizing referendum on Scottish independence. Brexit demonstrated just how much havoc a referendum can wreak, so this is perceived as a significant reduction in risk. After years of Brexit-imposed chaos, and then a disastrous start to its attempt to deal with the pandemic, politics suddenly looks like a reason to favor U.K. assets, rather than to avoid them. This is encouraging as U.K. stocks look cheap compared to the rest of the world. The particular mix of large companies quoted in the U.K., with large weightings of banks, resources companies and oil majors, and virtually no technology, means that the U.K. stock market will look cheaper than the rest of the world most of the time — as can be seen by the following chart, which compares the prospective earnings multiples on the FTSE All-Share index of British stocks to the multiple on the FTSE index for the world excluding the U.K. That gap was briefly eliminated in the months before the Brexit referendum, but it is now very wide:  Does this mean that U.K. equities really are a buy? Tapering will tend to keep the pound stronger, while the lack of it in the U.S., as long as this continues, should weaken the dollar. As for the chances of an economic recovery, the U.K. has the same kind of pent-up spending power as in the U.S. Capital Economics Ltd. of London estimates that British households have excess savings (compared to what would have been expected if last year's recession hadn't happened) of 140 billion pounds ($198 billion), about 6.6% of last year's gross domestic product. So the U.K. looks set to be a great test case for whether reopening will lead to a consumer splurge:  Britain's stop-and-start lockdowns over the last 15 months suggest that retail sales could recover in a big way. The current lockdown is unusually restrictive, as the government tries hard to avoid having to reimpose restrictions once again. Last summer's excited return to normality now looks like a bad mistake in terms of public health policy, but it does suggest that quite a consumer boom could be in prospect once lockdown is lifted for good:  Meanwhile, the BOE still looks unlikely to hike interest rates much, even if it withdraws stimulus in the form of asset purchases. According to Capital Economics, which is predicting virtually zero rates for years into the future, the market reduced its implicit expectations after the last BOE meeting, and now sees rates still below 1% in five years' time:  The weirdness of adjusting to Brexit could mess up a lot of these calculations, however. Imports boomed in the run-up to the Brexit trade deadline at the end of last year before slumping; they have since recovered much more impressively than exports. Any consumption boom is likely to suck in more imports. Britain's services sector, including the vital financial services industry, faces an uncertain post-Brexit future. And the EU's economy is likely to be weakened by Covid-19 for a lag of several months after the U.K. These are all reasons to expect a big trade deficit this year, which would take a bite out of growth:  But the bottom line remains that the U.K. looks well positioned to outperform most of the rest of the world. Its numerous self-inflicted wounds of the last five years have left it looking a little too cheap to ignore. And even those who don't invest there will want to keep a close eye on a country that is now guiding a course for others out of the pandemic. Survival TipsHere are some more musical recommendations courtesy of Apple, whose Apple Music program continues to prompt me to listen to songs and artists I hadn't listened to in years. First, I recommended World Party a few weeks ago. Try Rolling Off a Log from the album Egyptology; it's a small-scale masterpiece whose existence I'd totally forgotten. And then there is the late, great Ali Farka Toure. I went to Mali in December 1999; for some reason I and some friends thought it would be a great idea to see in the millennium in Timbuktu, where the locals had no concept of the millennium. It was an exciting trip, even if we ended up in the city of Segu, once the seat of an empire, and not Timbuktu on New Year's Eve. Mali is well known for its music, particularly Salif Keita (this song, Papa, is perhaps my favorite), but the musician who continues to haunt is the late Ali Farka Toure. Apple has now prompted me to listen to his album Niafunke, named after his home town, about a day's journey from Timbuktu. It's a series of exhortations to his fellow Malians to make something of themselves and to stick together in their difficult terrain — "God opened their mouths to eat either food to live or sand to die." Try listening to Hilly Yoro ("If a man has no eyes, Another can see…") or Allah Uya ("God is coming"), or Howkouna ("Worthy sons of Mali, Let us set to work, Only work can set men free…") or my favorite, Tulumba, ("The people of Mali have had enough of futile talk"), which sounds like something out of the Mississippi Delta. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment