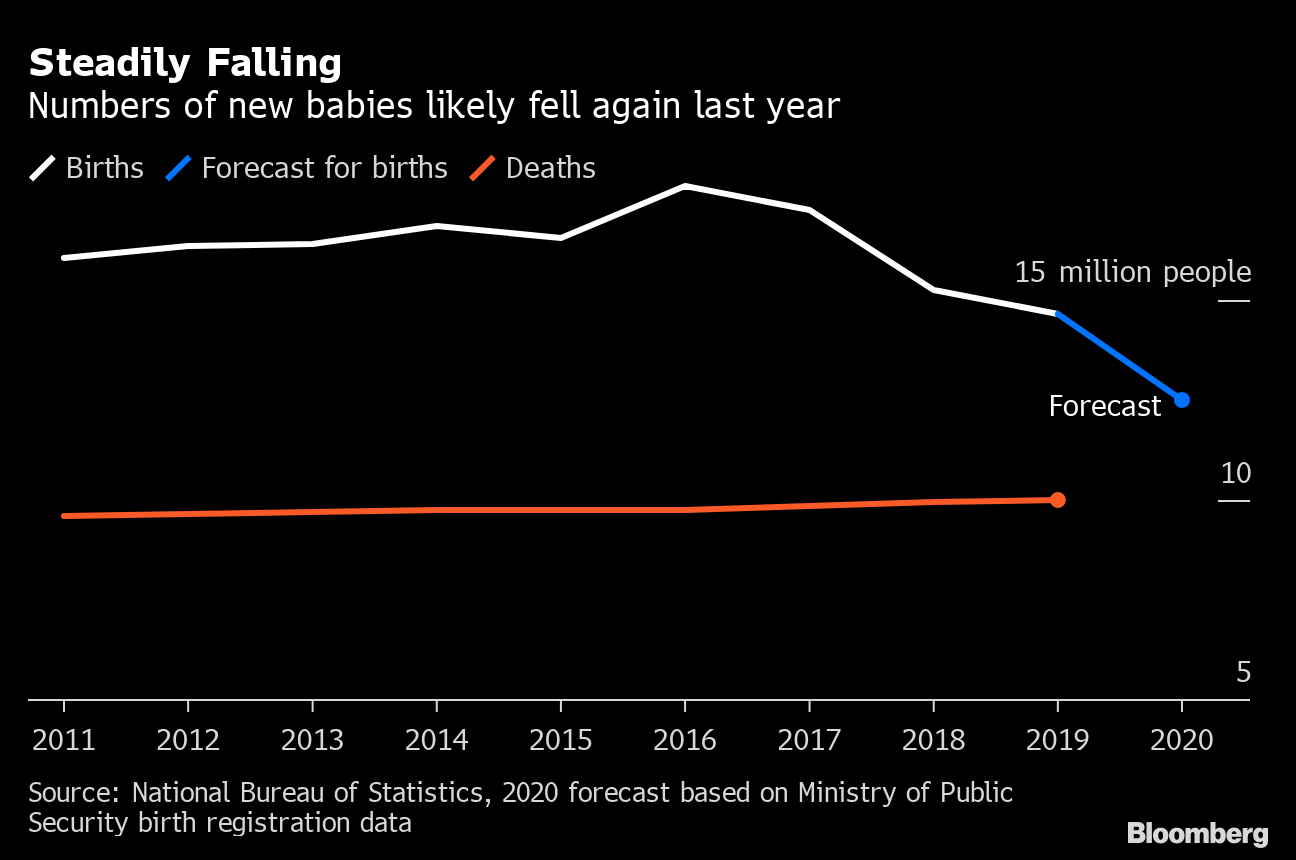

| China's headline economic statistics show growth bouncing back strongly from last year's virus-induced downturn. That's not, of course, the entire picture. At a national level, there is undoubtedly a robust recovery underway. Data released this week showed profits at industrial firms surged 92.3% in March from a year earlier. Meanwhile, an aggregate index of eight early indicators tracked by Bloomberg also showed strong economic activity extending into April. Look at growth regionally, however, and a different picture emerges. Guangdong, China's largest provincial economy, reported an 18.6% increase in GDP for the first quarter, ahead of the national pace of 18.3%. Jiangsu, the second-biggest provincial economy, expanded at an even faster 19.2%. That outperformance by China's biggest regional economies belies another fact: Many of the country's smaller provinces are underperforming. One example is Heilongjiang in the north, which is about a 10th the economic size of Guangdong. It grew 12.4% in the first quarter, well behind the national pace.  This divergence is not new. It developed over decades as exports and entrepreneurship bolstered provinces along the southern coast, while many parts of the coal- and steel-reliant north fell behind as those industries faltered. What's worrying now is that the pandemic may have worsened the divide. The implication for policy makers is significant, especially when it comes to the withdrawal of stimulus and what that will mean for the country's mountain of debt. Nomura noted in a report this week that the finances of regional governments in northern China were substantially more reliant on cash from Beijing than their southern counterparts. That means when corporate borrowers in northern China run into trouble, the ability of local authorities to help will be relatively limited. Indeed, northern China accounted for 60% of the country's bond defaults last year, Nomura pointed out. It should be said, though, that defaults are not necessarily a bad thing. They push lenders to be more disciplined, and they help channel money to the strongest borrowers. That's why the appearance of more delinquencies won't deter Beijing from shifting its economic focus to controlling risk and away from efforts to support businesses. What would give them pause is if those defaults hurt the real economy, such as through job losses. Looking only at the country-level data would be a good way to miss the earliest of such signals. Big Tech's TroublesFor those wondering if China's campaign against its biggest tech companies might be subsiding after Beijing levied a record fine against Alibaba and extracted pledges of obedience from dozens of other firms, this week provided a fairly firm answer: It's not. Beijing on Monday launched its first official anti-monopoly probe of a company outside Jack Ma's empire by targeting Meituan, best known for its army of yellow-clad food couriers. Tencent was in the spotlight shortly after, with Reuters reporting Beijing was preparing to fine WeChat's owner about $1.6 billion for not properly reporting past acquisitions and investments and for anticompetitive practices.  Meituan couriers gather in Beijing on April 21, 2021. Photographer: Yan Cong/Bloomberg It was also revealed this week that Chinese authorities are looking into how Ant Group's ill-fated IPO was fast-tracked last year. And then, as if to emphasize the point, regulators gathered the finance divisions of 13 tech companies on Thursday to tell them they'll be held to the same standards as Ant — including having to reconstitute those units as holdings companies that will be regulated like banks. Just how far will Beijing go in its crackdown? Our new documentary takes a closer look. Hong Kong VaccinationsCoronavirus infections in Hong Kong have been kept relatively under control. In our latest ranking of the best places in the world to be during the pandemic, the city ranked 10th, higher than the U.S., the U.K. or Canada. But success comes with its own challenges. For Hong Kong, the low rate of infections has left many residents complacent about getting vaccinated. That combined with a distrust of government fueled by the 2019 protests and concerns about the efficacy of vaccines have resulted in only about 11% of the population getting at least one shot. To change that, Hong Kong is turning to incentives. This week, it started letting bars, nightclubs and karaoke parlors to reopen and operate past midnight, but with complex vaccine requirements for staff and customers. It also announced a travel bubble with Singapore — again, only for vaccinated Hong Kong residents, though there's no such requirement for people in the city-state. Whether that's enough to do the trick, however, will take some time to tell. Peak PopulationChina's population is undoubtedly nearing a peak. A combination of the one-child policy, better education for women and the rising cost of raising a child has fueled a rapid decline in the country's birth rate. What's unclear, of course, is when that will happen. There was speculation this week China might have already reached that turning point in 2020, after a Financial Times report Tuesday on as-yet-unreleased census data. By Thursday, the statistics bureau publicly refuted that in a brief statement, noting the population grew in 2020. Whether that turning point is in 2020 or 2025 — as a leading demographer previously forecast — the impetus to act is the same. A shrinking population would be a drag on economic growth, and make it more difficult to pay for services such as pensions and health care. Indeed, China's central bank had already called for enacting policies that increase the birth rate. A new spotlight on the issue might help make those measures a reality.  What We're ReadingAnd finally, a few other things that caught our attention: Want the latest on the fast-changing world economy and what it means for businesses, policy makers and investors? Sign up to get The New Economy Daily in your inbox.

|

Post a Comment