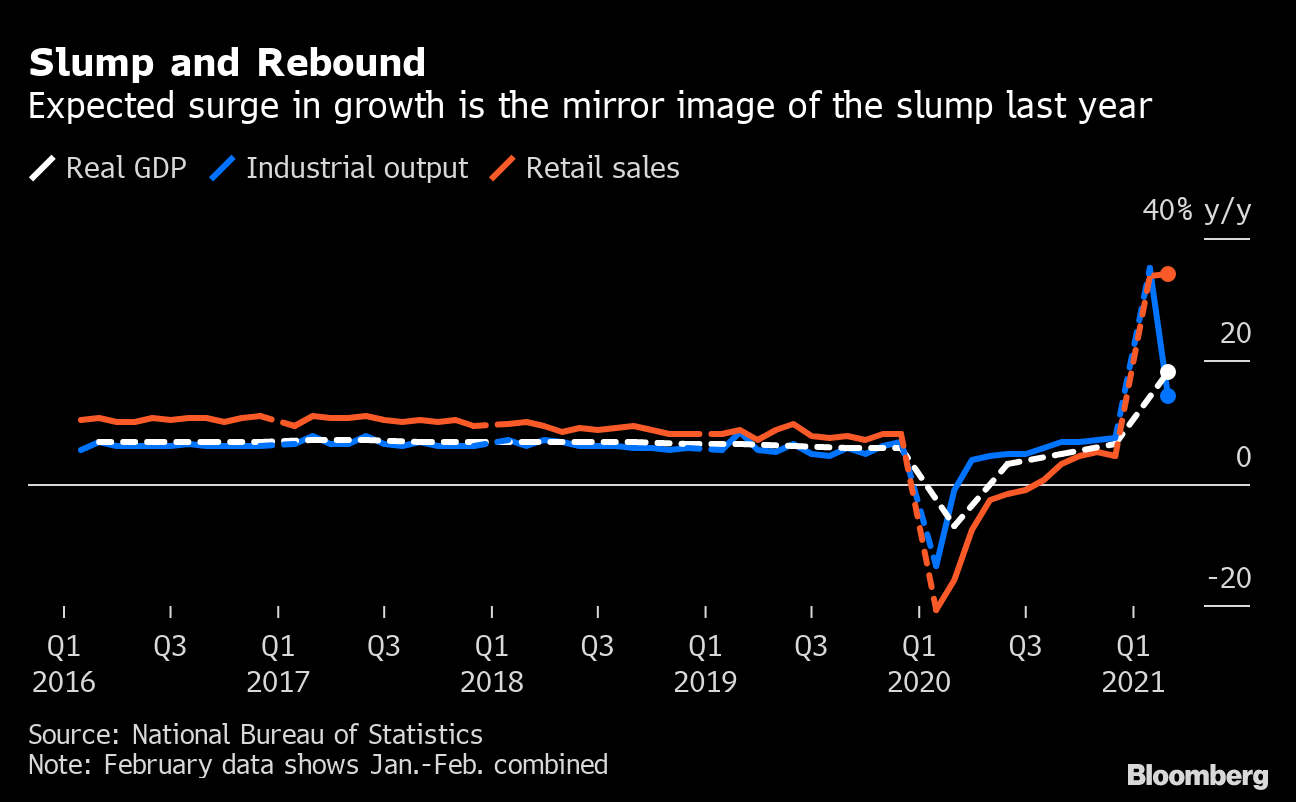

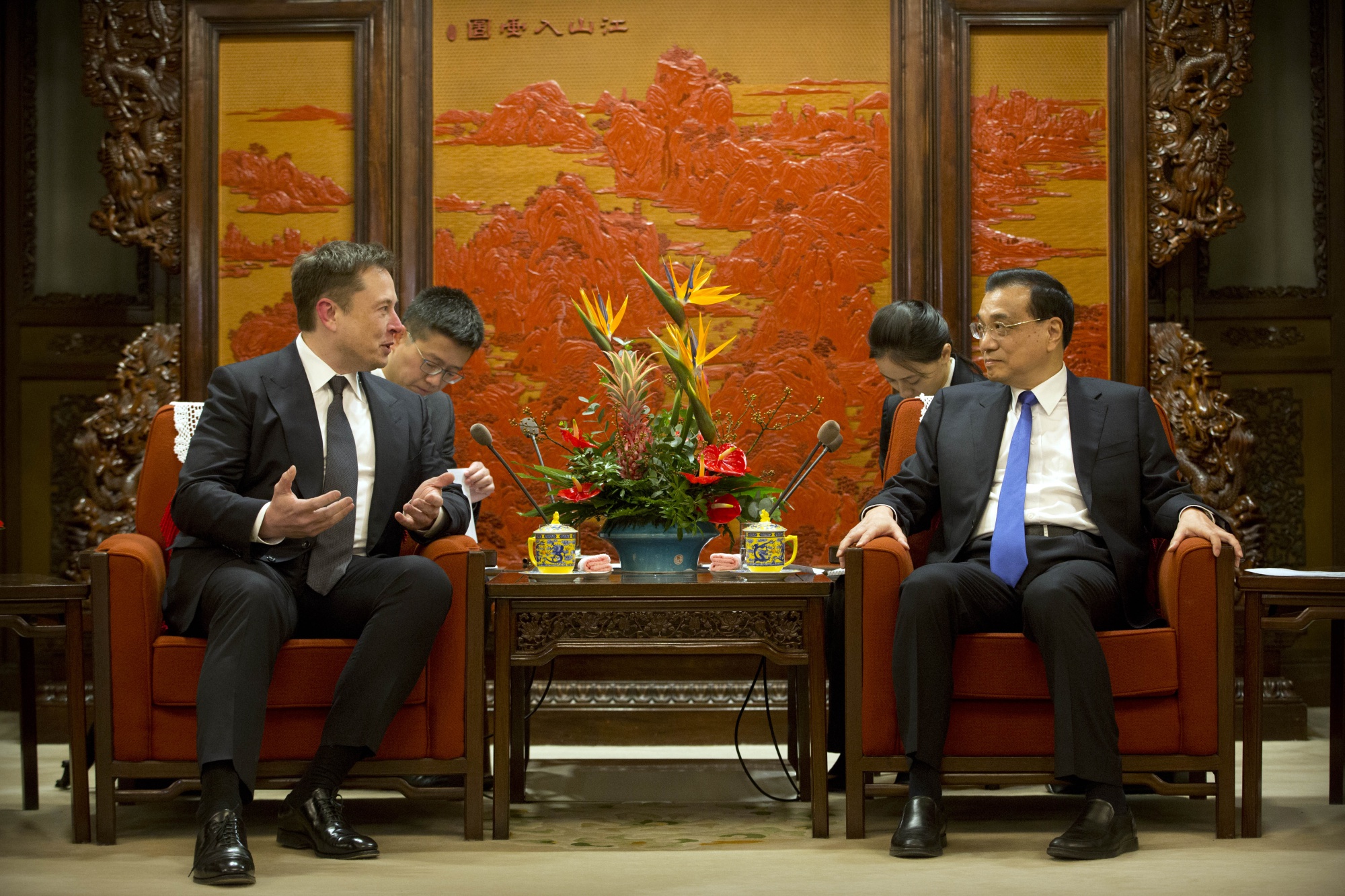

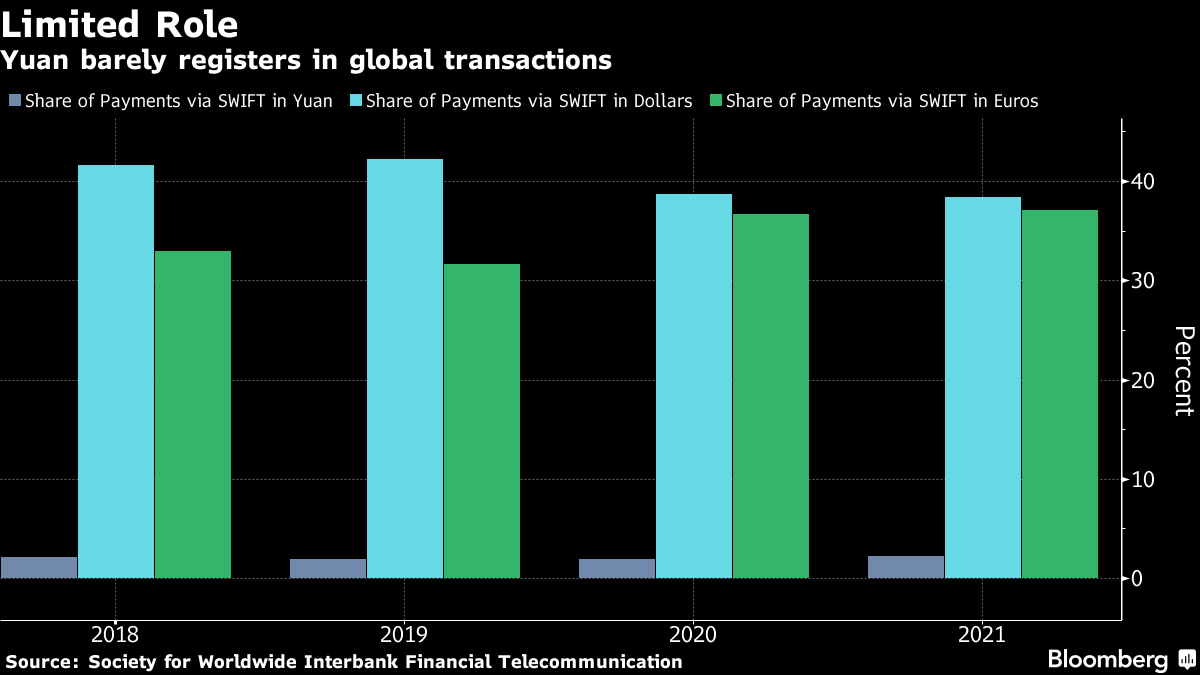

| Knowing where China's red lines are when it comes to everything from diplomacy to business is quintessential to understanding Beijing's priorities. What makes doing so a challenge is that the lines can move. The term red lines is used by Chinese officials to denote issues for which the government's position is nonnegotiable and not to be challenged. Beijing's claim of sovereignty over Taiwan is perhaps the best-known, but the term is also applied in sectors from finance to technology. In real estate, for example, China introduced three red lines in the second half of last year to tackle rising levels of debt among its developers. The rule covered three ratios of indebtedness and forced companies to show they were below caps set by Beijing before they could borrow any more. This prompted property firms to rapidly cut leverage, spin off assets and raise capital. Indeed, data compiled this week showed that almost half of China's 66 biggest developers were in compliance at the end of 2020, versus 14 six months earlier. The impact of shifting red lines was even more pronounced in the bond market this week. There, the question that preoccupied investors was if Beijing would rescue China Huarong Asset Management. Set up in 1999 to manage bad debts unloaded from China's state banks and majority owned by the finance ministry, Huarong had long been seen as too important to fail. That's been thrown into question after the company ran into trouble and authorities in Beijing chose to stay quiet. While the number defaults by state-owned companies has increased substantially in the past year, the overwhelming majority of issuers who've missed payments were owned by local governments, not Beijing. And none were considered as systematically important as Huarong.  It is still too early to know how Huarong's situation will ultimately be resolved, but if it were to end poorly, investors will be left wondering where Beijing's red lines start and finish when it comes to bailouts. The situation for big tech was far more certain. After fining Alibaba a record $2.8 billion over the weekend for abusing its market dominance, Chinese regulators then gathered 34 of the country's top internet firms in Beijing this week to lay down the new red lines. They included a ban on using acquisitions to squeeze out rivals, prohibiting the use of exclusivity pacts to lock in merchants and better protection of data. Meituan, ByteDance and JD.com were just a few of the companies that quickly issued public pledges to obey the rules. While the issues with big tech, Huarong and real estate all have their own intricacies, there's also one theme that pulls them together: China's leaders are more intent than ever on reining in risk, and the red lines for business are shifting accordingly. Base EffectsLooking just at the blowout GDP growth figure China reported Friday would suggest that the world's second-biggest economy is going gangbusters. Indeed, it is not every day that you see a $14 trillion dollar economy grow by 18.3%. But of course there's more to it.  What that growth number shows is how much the economy grew in the first quarter this year when compared with the same period in 2020 — and this time last year the economy was in terrible shape. Pummeled by the pandemic and government-imposed lockdowns, GDP shrank 6.8% in the first three months of 2020. In other words, things are not as they appear. The quarterly expansion in GDP was in fact a weaker-than-expected 0.6%. While the figure does contain some seasonal differences, the weeklong Lunar New Year holiday in February for example, it does in this instance seem to offer a better summation of the current state of affairs. The economy is growing but uncertainty still abounds. Climate Vs InflationU.S. climate envoy John Kerry was in Shanghai this week to meet with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua. The two were set to discuss "raising global climate ambition," according to the U.S. State Department. Pushing Beijing to ramp up its fight against emissions could be more complicated than it first appears. When thinking about how to tackle climate change, Chinese policy makers have long had to balance the need for jobs with the desire to protect the environment. The same can be said for many governments around the world. More recently, however, a new wrinkle to this debate has emerged. Rising commodity costs are fueling a surge in China's producer prices, which measure how much businesses are charging for the goods they churn out. Data released this week showed those prices increased in March by the most since July 2018. That's fueling concerns that the level of inflation consumers feel could also be moving higher soon, and not just domestically. Because China is such a huge exporter, higher prices charged by Chinese businesses could trickle down to consumers around the world.  This is where it gets complicated for China's climate ambitions. For example, Beijing is pushing steel mills to reduce production this year in a bid to lower emissions, pushing costs higher. And any additional climate commitments could fuel additional increases. Beijing and Washington will need to weigh such consequences as they set their green goals. Mending TiesIn addition to climate change, Kerry's visit to Shanghai was also notable as the first by a senior member of President Joe Biden's administration since he took office. Both Beijing and Washington were quick, however, to tamp down any speculation that this could be a turning point in ties. Hu Xijin, the editor of the Global Times newspaper who has in the past revealed Beijing's intentions before a formal announcement, said Kerry's visit was not an ice-breaking exercise. Kerry himself told the Wall Street Journal before leaving for Shanghai that he wanted to hold China accountable for its climate pledges, and wouldn't compromise on economic and human-rights issues. None of that was especially soothing. At the same time, however, there have been attempts in other venues at mending ties. That was most notable this week in China's efforts to bolster its relationship with American businesses. The country's top economic-planning agency, for example, called together China-based executives from an array of American companies, including Tesla, Qualcomm and Dell, to discuss Beijing's new five-year plan. Separately, Premier Li Keqiang spoke to U.S. business leaders on a video conference hosted by former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. There will be even more next week. That's when luminaries of American business including Elon Musk and Tim Cook are scheduled to participate virtually in China's Boao Forum.  Elon Musk with Li Keqiang in Beijing in January 2019. Photographer: Pool/Getty Images Iris Pang, chief Greater China economist at ING Bank in Hong Kong, said Beijing might be trying to show Washington that China should be thought of as a market for American goods, not as a supplier. It's a far less appealing proposition to decouple from one's customers. Digital YuanChina's efforts to roll out its digital currency are beginning to gather momentum, judging by events of this past week. One such indication came from Macau. The gambling hub's chief executive said this week that the government plans to amend local laws on what can be used as legal tender and added that the city would work with China's central bank to "study the feasibility of issuing a digital currency." Authorities in Macau had late last year already started discussing with casinos the possibility of having gamblers use the digital yuan to buy chips. That plan appears to be moving forward, despite worries in the gaming industry that a digital currency, which is far easier for the government to track, could scare off high rollers. The U.S. is also starting to pay attention. The Biden administration is stepping up its scrutiny of China's plans for the digital yuan, with some officials concerned that the rollout could kick off a long-term bid to topple the dollar as the world's dominant currency. If the yuan does supersede the dollar, it won't be anytime soon. Today, the role of China's currency in global investment and commerce is just a fraction of the dollar's. Far more likely in the near term is that Beijing's push forward with the digital yuan will give Washington greater impetus to develop a digital dollar.  What We're ReadingAnd finally, a few other things that caught our attention: |

Post a Comment