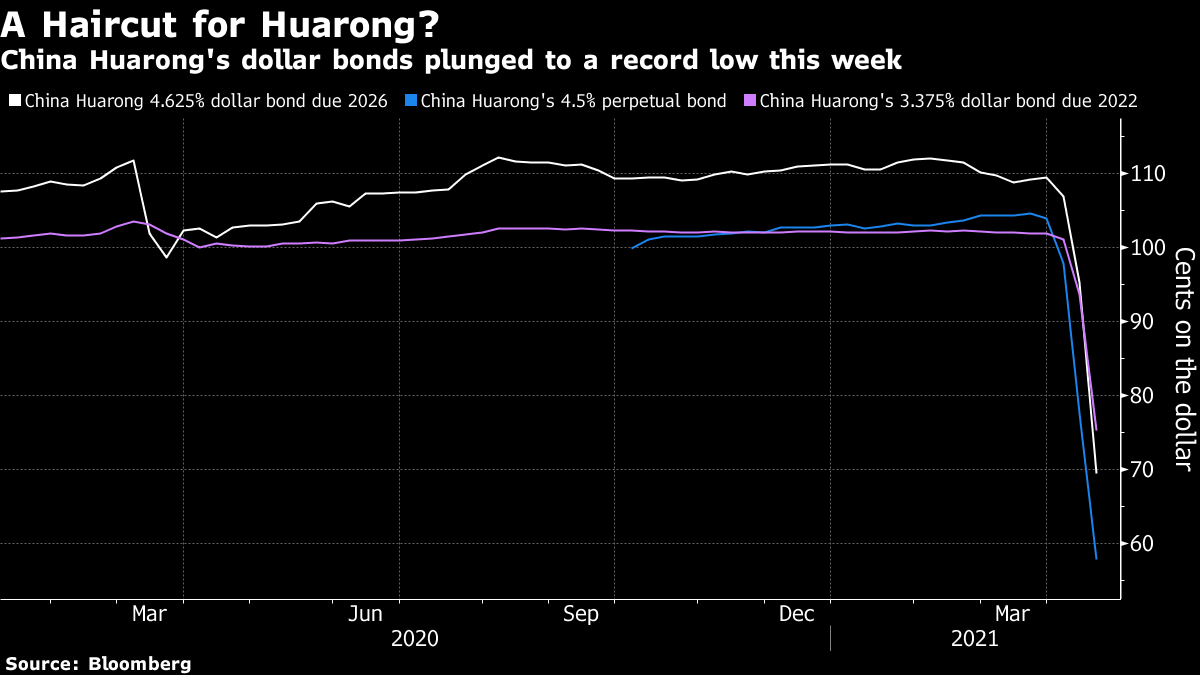

| The U.S. orders fresh sanctions on Russia. A Chinese distressed debt manager gets investors worried. Covid-19 is more deadly in some countries than others, and no one knows why. Here's what you need to know to start your day. Investors are getting very nervous about China Huarong Asset Management's public silence on details of its overhaul plan. From Hong Kong to London to New York, questions burn about the state financial company, which borrowed $23.2 billion on overseas markets before getting ensnared in a sweeping corruption crackdown. Are key state-owned enterprises like Huarong still too big to fail — or will international bond investors have to swallow losses? And with millions of dollars of bonds maturing this month, can the firm make good on its imminent debt payments? The company says it has "adequate liquidity," and overseas bonds rallied Thursday. With some $7.4 billion of bonds due to be repaid or refinanced this year, new funds are needed. Another key question is when Huarong will release earnings, which should shed light on its plans. Asian stocks look poised to gain after surprisingly robust economic data helped propel U.S. benchmark indexes to records. Yields on benchmark 10-year Treasury notes declined. The S&P 500 Index's advance was led by real estate and health care, while rallies in technology shares also lifted the Nasdaq 100. Elsewhere, China is expected to report the highest quarterly economic growth ever since it began releasing such data 30 years ago. But investors will need to look beyond that number to assess the state of the Chinese economy's post-pandemic recovery. Bitcoin gained and Coinbase fell despite news that three funds at Cathie Wood's Ark Investment Management bought shares at Wednesday's debut of the largest digital asset exchange. Oil extended gains from Wednesday's surge. Covid-19 is much more deadly in Brazil than India, and nobody knows why. When it comes to the scale of infections, the two nations are similarly matched. But Brazil has seen more than 361,800 people die from the virus — more than twice as many as India, which has a far larger population. Factors such as mean age and the quality of India's death statistics may be at play, but don't entirely explain the disparity. Experts say this needs to be better understood to contain this global outbreak and to avoid future public health crises. Elsewhere: Global vaccine production surpassed 1 billion doses this week; Hong Kong will prohibit flights from Singapore by budget carrier Scoot after two passengers were confirmed to have Covid-19 on arrival; and the U.K. is warned that a "dangerous wave" of infections is on its doorstep. In a speech that could inflame tensions with China, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison will tell India's premier geopolitical conference that the world is moving toward "a great polarization" between authoritarian states and liberal democracies. Australia is increasingly reaching out to what Morrison describes as "like-minded liberal democracies," including the U.S. and fellow Quad partners India and Japan, in a bid to counter what his government sees as an increasingly assertive China in the Indo-Pacific region. Meanwhile a new gauge shows increased tensions meant foreign investment uncertainty in Australia jumped in 2020. Here's more on who China is falling out with, and why. U.S. President Joe Biden has ordered fresh sanctions on Russia, including restrictions on buying new sovereign debt, in response to allegations that Moscow was behind the damaging hack on SolarWinds and interfered with last year's U.S. election. The new measures sanction 32 entities and individuals, and 10 Russian diplomats in Washington will be expelled. Publicly, officials responded angrily: "This aggressive behavior will of course meet with a decisive rebuff," a Foreign Ministry spokeswoman said. But even as Russia vowed to retaliate, the Kremlin signaled it remained open to the White House's offer of a presidential summit. What We've Been ReadingThis is what's caught our eye over the past 24 hours: And finally, here's what Tracy's interested in todayThe specter of default hovering over a Chinese company used to lead to a familiar pattern. Risk premiums on the firm's bonds would actually fall (spreads would tighten) as the threat of default materialized. That's counter-intuitive of course, but indicative of how investors viewed the dynamic between China's corporate debt market and its government; they simply assumed authorities would rescue any important entities that got into trouble. As the drama around Huarong Asset Management shows, however, that pattern of behavior has shifted as China continues its efforts to move investors away from the assumption that it will always bail out state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The idea here is that China wants to eliminate the moral hazard that's long been embedded in its capital markets and generate a more accurate pricing of risk that will further attract outside investors and inflows. Spreads have climbed for the weakest SOEs and defaults have picked up. When it comes to Huarong's bonds, spreads have blown out on its dollar debt as investors price in the real possibility of a deep haircut instead of a bailout.  But if allowing Huarong to default is intended to mature China's capital markets, it's arguably a terrible vehicle for doing so. Not only is Huarong the ultimate SOE — a bad bank created by the government and majority-owned by the finance ministry — but it also has a huge amount of debt that's landed in almost every portfolio with exposure to Chinese bonds. Contagion is a real possibility. More importantly, the Huarong saga is arguably a political drama rather than a market-driven one, a point eloquently suggested by my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Shuli Ren. Huarong was one of four bad banks created to sweep up soured loans and other distressed assets from the financial system. Instead the company was buying high-yielding bonds and other financial products, rogue behavior which along with charges of corruption and bribery has resulted in the execution of its chairman. But Huarong's adventures in diversification were hardly a secret. They've been known and written about for years, while China's authorities presumably stood by. It's doubtful that a Huarong haircut will do anything to convince foreign investors that China's market isn't an opaque morass of secretive political maneuvering that's impossible to price. You can follow Tracy Alloway on Twitter at @tracyalloway. |

Post a Comment