Lead Us Not Into InflationAfter today, I will try to write the next five newsletters without mentioning the word "inflation." It will be difficult but I'll give it a try. If you weren't able to join my liveblogged conversation with Mohamed El-Erian, Bloomberg Opinion columnist and president of Queens' College, Cambridge, you can find the transcript here. Given El-Erian's past role as co-chief investment officer of Pacific Investment Management Co., his views on inflation and the bond market command a lot of attention, and I'd like to thank him again for taking part. A Cliff's Notes version of his outlook would be as follows. First, El-Erian thinks the Fed needs to find a way to exit its extremely loose monetary policy, and that it runs a risk by delaying a start to the process. As he put it: The good news is that there is still a window for the Fed to exit in a relatively orderly manner, though it is getting smaller and smaller by the day. Indeed, the longer the Fed delays signaling a moderation of its uber loose monetary policy, the smaller the window and the greater the immediate and longer-term risks to the economy, the markets and the credibility of the Fed.

Naturally, there were questions about what might happen once the Fed tries to tighten. He was offered a choice between a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum (and I think we've already had a repeat in a minor key during the first quarter, as the rise in bond yields translated into problems for emerging markets), an LTCM moment, or a full-blown Lehman Moment. At least he didn't choose Lehman: As to what ultimately may happen if the Fed misses the window, I suspect it is somewhere between a May 2013 taper tantrum and a 2008 Lehman moment. Specifically, we would have significant market volatility and a risk of market malfunction, as we experienced during the taper tantrum. Together these could act as a headwind to the economic recovery. But I don't think we would repeat the sudden stop for the financial system, for banks and for the payments and settlement system (all of which followed the Lehman moment).

A Fed exit is bound to cause some pain. After all, it's never fun to go without any more punch from the punch bowl just as you were beginning to enjoy it. But his view of the scenarios is also a tad alarming. There would be a spike in yields... and I suspect that it would happen under all of the following Fed policy scenarios: timely exit, delayed exit, and slamming the brakes. The differences would be in timing and in the shape of the yield curve. In terms of numbers, it would be a 2% to 2.25% 10-year yield initially under the first scenario, more of a hockey stick under the second scenario, and higher than both under the third scenario. I would also add that the response of endogenous (market-based) flows -- important as they serve as stabilizers —- would be highest under the first and weakest under the third. I am thinking here of foreign buying, liability-matching flows, etc…

What exactly would force the Fed's hand? El-Erian suggests that a 3% headline rate of inflation at some point this year is more or less a formality, and not enough on its own to force the Fed to change course. We all understand the importance of base effects after last year's turmoil. What matters more is the duration of higher inflation. The key word in Fed communications of late, which is likely to be repeated at next week's Federal Open Market Committee meeting, is "transitory." The Fed thinks the inflation we will almost certainly experience this year will be fleeting. Any removal of "transitory" would be a clear sign of a move in a hawkish direction; and any clear evidence that inflation will persist would leave it with no choice. To quote El-Erian: reading between the lines and based on what top Fed officials have said recently, I would guess a 2.5% to 3% rate that persists for the last six months of this year would force the Fed's hand. Many markets, including equities and EM, have benefited from record loose financial conditions and, more

generally, investors' full embrace of the liquidity paradigm underpinned by central banks' ultra supportive policies. The good news is that this has allowed many companies and corporates to refinance themselves, delaying debt challenges and enabling quite a bit of financial engineering that has benefited Wall Street much more than Main Street. But it does expose market segments to liquidity risks and, as we have seen on a few occasions in the recent past, this is not just an issue for the traditionally less liquid segments

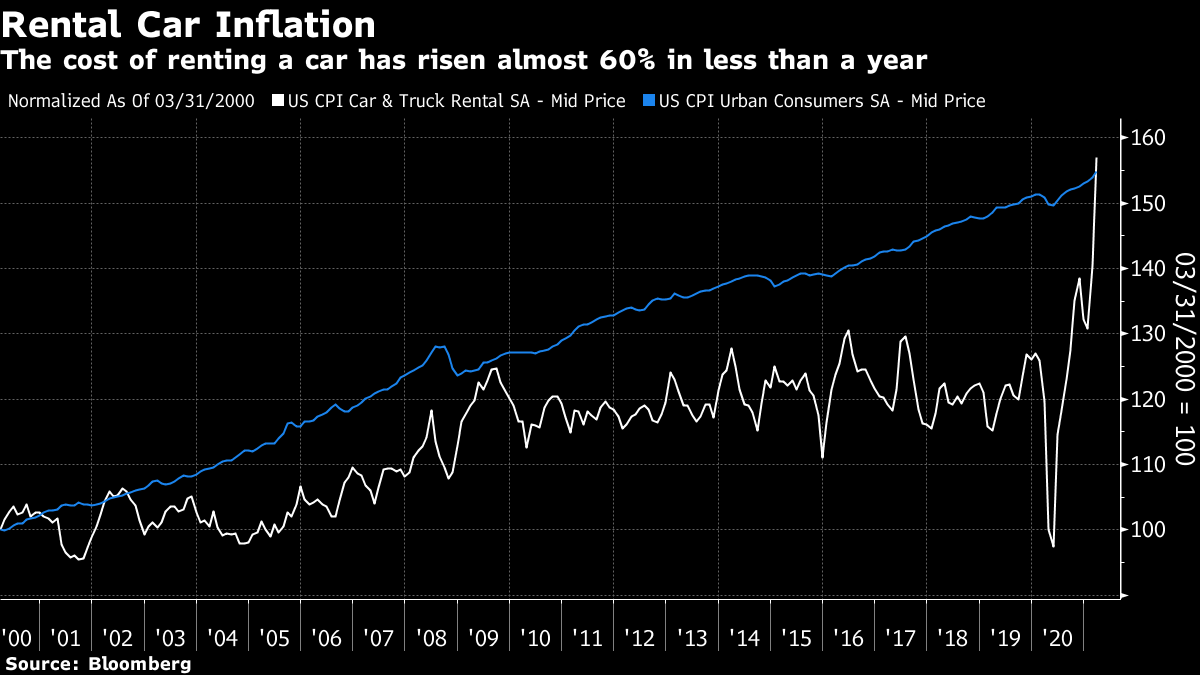

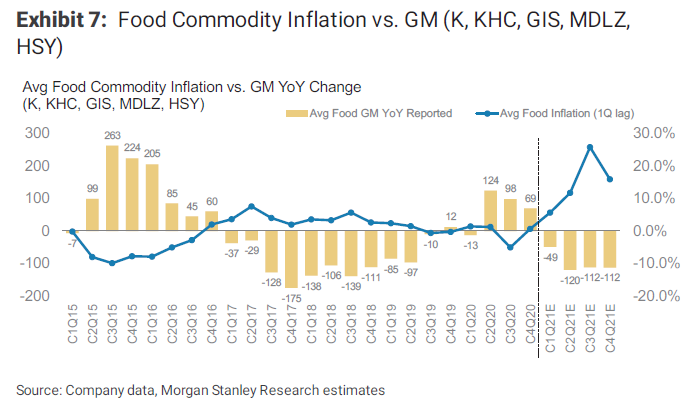

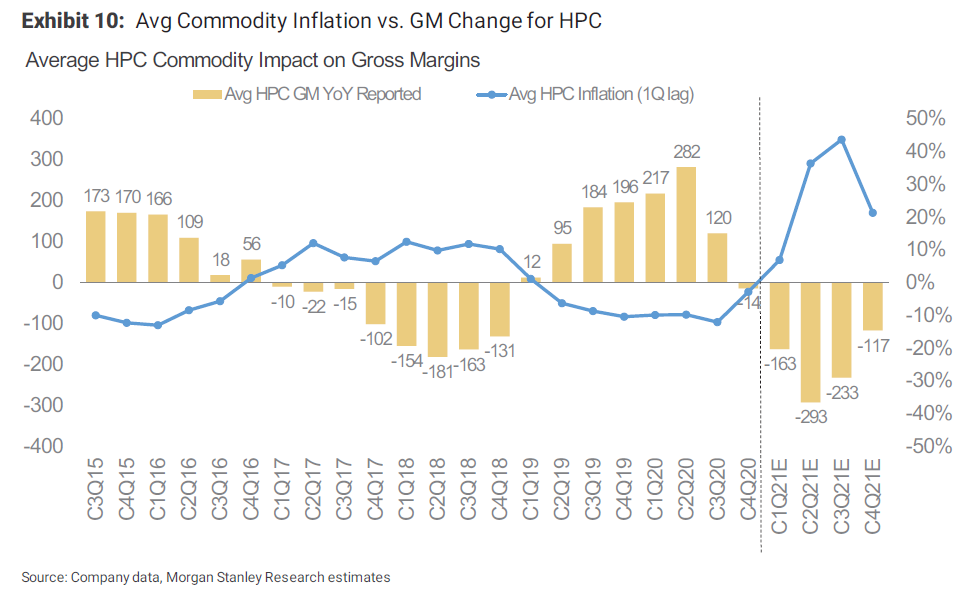

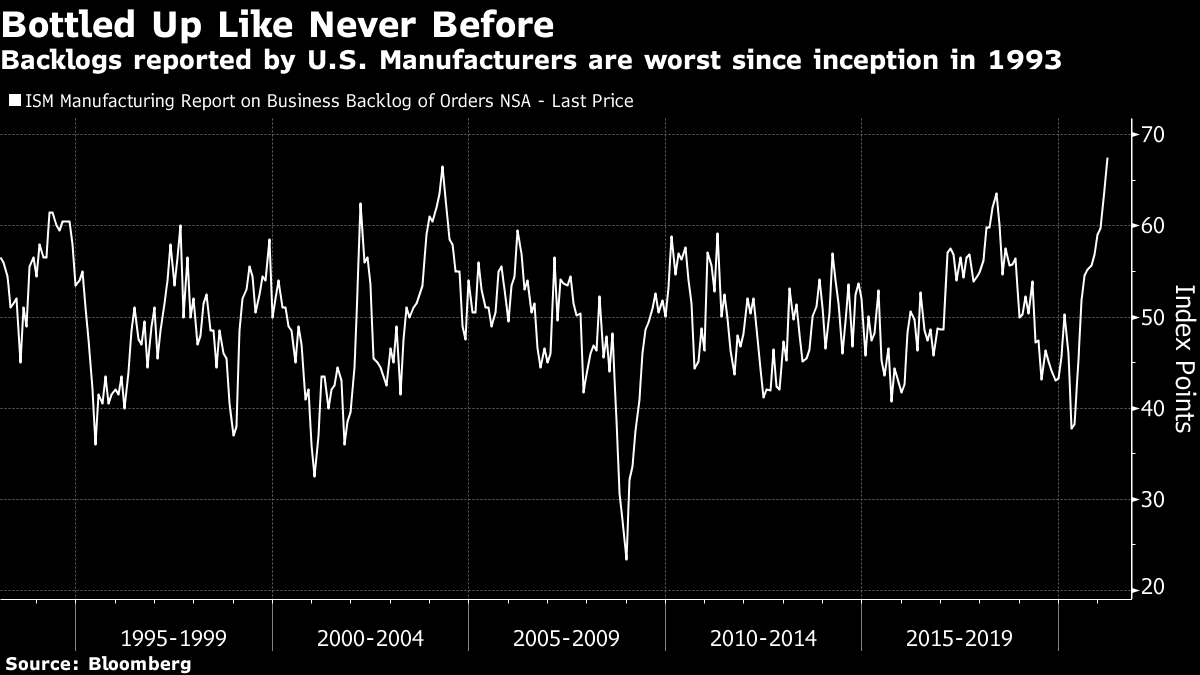

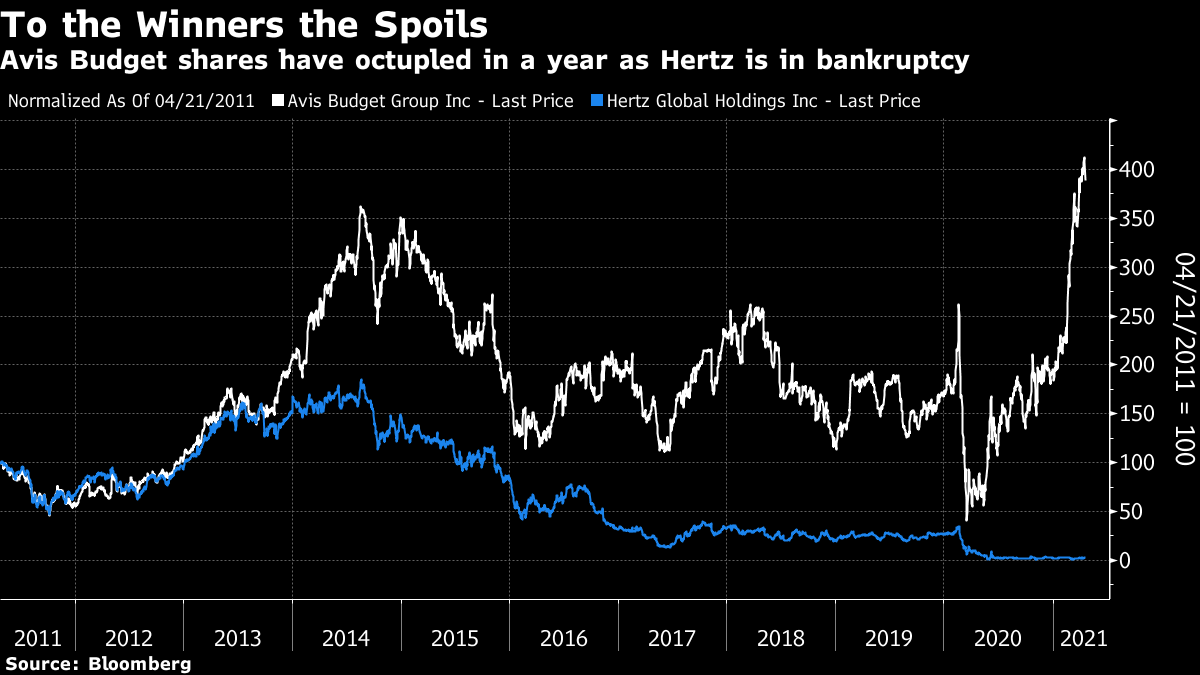

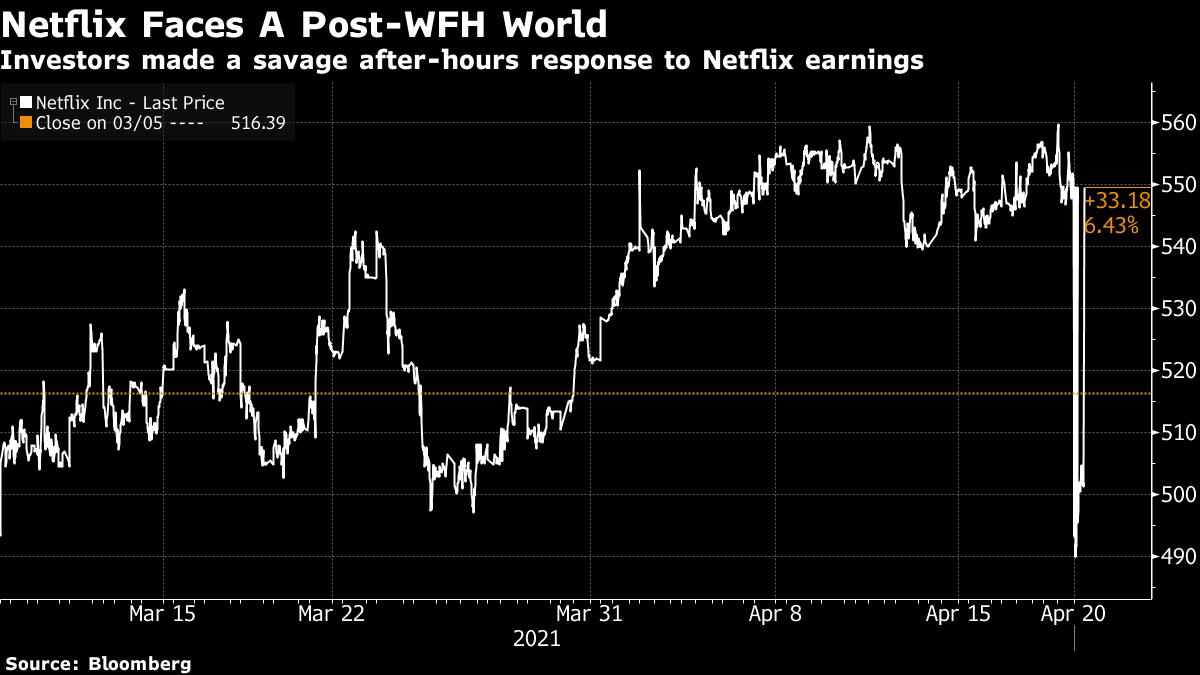

That, expressed in El-Erian's typically measured and judicious tone, is the inflationary outlook as he sees it. This is a difficult juncture. Inflationary SnapshotsNow I'd like to offer a few inflationary vignettes, as everyone tries to put together what is happening. A look at the detail of the consumer price index suggests there is some startling inflation at present in the sectors that were worst affected by the pandemic. The cost of renting a car had been remarkably stable, having risen far less than the general price level over the course of the last two decades; that has changed with a vengeance in the last few months:  Having surged by almost 60% over the last 10 months, car rental prices are highly unlikely to do so again over the next 10. This has the look of a remarkable but transitory effect. Such effects can lead to misjudgments and have broader consequences, but it does look reasonable to assume that this won't endure. Pricing Power The concept of pricing power matters greatly. A research note from Morgan Stanley suggested that consumer staples' earnings are in for a tough time, because companies won't be able to pass on all of the inflation in their raw materials to consumers. The following is the Morgan Stanley estimate of gross margins for a range of food manufacturers (their ticker symbols are given in the graphic), compared to average food price inflation with a quarter's lag:  This is the same exercise repeated for a group of household products manufacturers. Again, the likelihood is that higher material prices will just mean a nasty hit to profits, rather than a pass-through into higher inflation.  Cost-Push For those concerned about the risk of inflation taking hold from shortages or bottlenecks, an index kept by the Institute of Supply Management as part of its PMI calculations makes interesting reading. There is every reason to think that bottlenecks will inflict some inflation on us this year:  There wasn't any great spike in inflation after record backlogs in 2004, but this does look like evidence of a problem ahead, which should prove transitory. Whether companies can pass such costs on to consumers will depend on their pricing power, about which we will soon know a lot more. Winners and Losers This environment is creating winners and losers, and opportunities to make and lose a lot of money. The increase in car rental prices seems to have done a power of good to the shares of Avis Budget Group Inc., whose shares have risen eightfold since the bottom last year. Meanwhile, its great rival Hertz is in bankruptcy — although it is easy to understand why there is an increasingly energetic bidding war for the company:  Meanwhile, results from Netflix Inc. after the market closed Tuesday seem to have awoken investors to the thought that demand for streaming television might dip once people no longer have to work from home. The company suffered its worst first quarter in eight years, adding only 3.98 million subscribers, compared with an average analyst estimate of 6.29 million and its own forecast of 6 million. When a company lags its own forecast this badly, a big negative reaction on the market is only to be expected:  What is surprising, though, is how surprising it seems to be to investors. There is probably further to go in the rotation from Covid beneficiaries to Covid victims. And the streaming services are about to find out a lot about their pricing power. Survival TipsThe spirit of sport survives! The European Super League is no more! To celebrate, maybe try listening to Vindaloo, a great soccer anthem whose video borrows from the Verve's great Bittersweet Symphony. And here is a look back to the good old days of 1979, when the European Cup final was played between teams from the small cities of Nottingham and Malmo. The scorer, Trevor Francis, was the first player ever to command a transfer fee of as much as 1 million pounds ($1.39 million); there has been some inflation since then. Meanwhile, the European mega-cities of London, Paris, Berlin and Istanbul, the four biggest on the continent, have only one European Cup between them. It's great that the likes of Nottingham Forest and Malmo will still have a chance to win the biggest prize. And it's also great that unfashionable teams like Brighton get the chance to score wonder goals against rich teams stuffed with money like Chelsea. Long may it continue. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment